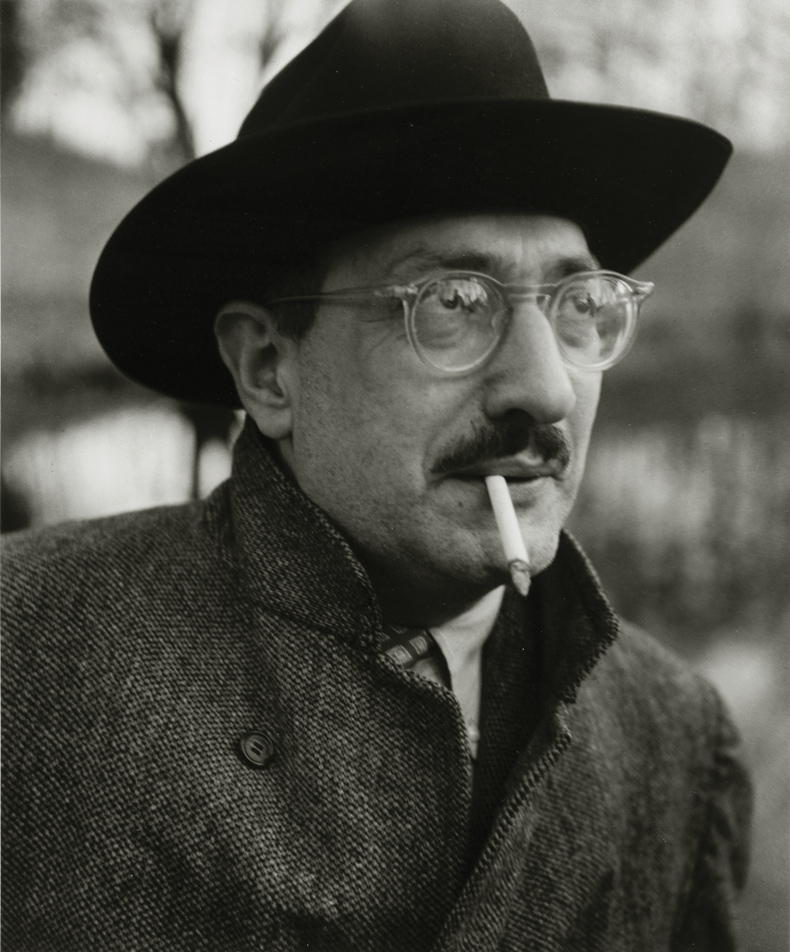

In the dying days of 1962, the art historian Dora Vallier went to the Mark Rothko exhibition that had recently opened at the Musée d’Art Moderne (MAM) in Paris. This was to be the last stop on a triumphant, year-long tour of Rothko’s first retrospective, which had set off from the Museum of Modern Art in New York and moved on to London, Amsterdam, Brussels, Basel and Rome. To Vallier’s surprise, though, she found herself alone in MAM’s cavernous basement galleries.

The reason for this, or at least part of it, was the weather. Three weeks before Rothko’s show opened on 5 December, France had been hit by her hardest winter for a century. The ground froze to a depth of 60 centimetres; it wasn’t to thaw again until March, two months after MAM’s Rothko exhibition had closed. Parisians, frost-averse, stayed at home.

Red on Maroon (1959), Mark Rothko. Tate collections. Photo: © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko/ADAGP, Paris, 2023

There was another froideur behind MAM’s disastrous visitor numbers, however. Parisians may not like the cold, but they do like to be seen as up to date. Not for nothing is dernier cri a French term. The critic Michel Ragon, although a keen Rothko fan, couldn’t help but remark that Abstract Expressionism was, by 1962, old hat – ‘ancient history’, as he put it – supplanted in the fashion stakes by the latest arrival, Pop art. Rothko wasn’t even the first AbEx painter to be shown at MAM, Jackson Pollock having beaten him to it in 1959 with a solo exhibition metonymically entitled ‘La Nouvelle Peinture Americaine’.

Beyond this, too, was a lingering suspicion that Abstract Expressionism was in reality French, an offshoot of the School of Paris taken to New York in the war by exiles such as Marc Chagall and Jacques Lipchitz and stolen there by the likes of Pollock and Rothko. When the glint-eyed New York dealer Samuel Kootz had shown a selection of AbEx paintings at the Galerie Maeght in Paris in 1947, French critics had been quick to denounce the theft. ‘Those Americans […] are from the École de Paris,’ spluttered one; another, feigning concern, asked why ‘no autonomous school [wa]s taking off in the United States.’ The venerable newspaper, Le Monde, dismissed the work in Kootz’s show as ‘nothing new’, adding that ‘this so-called “American” painting is at heart just European.’

The Rothko exhibition that opens at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris this October thus comes with a specific local history. There have been two full-scale monograph shows of the artist’s work in the city since 1962, both held at MAM, although neither, prudently, in winter. The last was a quarter of a century ago, in 1999.

No.9 / No.5 / No.18 (1952), Mark Rothko. Private Collection. Photo: © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko/ADAGP, Paris, 2023

Given the outburst of Franco-chauvinism that greeted Kootz’s AbEx exhibition, it may seem surprising that the question of Rothko’s European-ness should be at the heart of this new show. Its focus, though, is far broader than the narrow question of what the painter may or may not have taken from exiled Parisians in wartime New York. The Louis Vuitton exhibition is a homecoming, but less to Paris than to the continent and culture Rothko had left behind as a ten-year-old boy when, in 1913, his parents took him from Latvia to Oregon via Ellis Island.

It would be nearly four decades before he returned to Europe. In March 1950, recovering from a nervous breakdown brought on by the death of his mother, Rothko set off on a five-month tour of Italy and France. With his second wife, Mell, he visited Siena, Arezzo, Venice, Florence and Rome. It was the post-war crumble of Paris that he found most ‘engaging to the eye’, though, as he wrote home to his friend, the painter Barnett Newman, ‘impressive because of its ugliness’. ‘A street of buildings in good repair is unendurable,’ Rothko went on. ‘Morally one abominates a devotion to […] the monuments which commemorate nearly every- thing which I, and France, too much abhor.’

For all that, it was in Florence that he saw the work that would most bewitch him: the Medici’s Laurentian Library, and specifically its ricetto, or vestibule. He would return to the city on a second European trip, in 1959. As Rothko told a journalist on the ship from New York to Naples, Michelangelo’s spare, square, pietra-serena-and-white space ‘achieved just the kind of feeling I’m after – he makes the viewers feel that they are trapped in a room where all the doors and windows are bricked up, so that all they can do is butt their heads forever against the wall.’

This admiration would find its unlikely expression that same year, in a suite of paintings of which nine are now in Tate Modern, although they were originally intended for Mies van der Rohe’s new Seagram Building in New York. It was only after the burningly left-wing Rothko had made 30 canvases for Mies’s skyscraper that he decided that the thought of rich diners looking at them as they ate – the paintings were to be hung as murals in the Seagram’s grande luxe Four Seasons restaurant – disgusted him beyond bearing.

Despite his openly voicing the hope that the work would ‘ruin the appetite of every son of a bitch who ever eats in that room’, Rothko’s clients professed themselves happy, and persisted. In the end, the artist cancelled the commission himself, returning his advance and distributing the finished works among various museums, of which one was the Tate.

If the so-called Seagram Murals mark a high point in Rothko’s art, they also suggest a change in his thinking. The Fondation Louis Vuitton has pulled off a number of coups with its borrowings for this show, one of the most impressive being the loan of what the Tate calls its Rothko Room. This has been recreated in its entirety for the exhibition, in the configuration stipulated by the artist himself when he gave the works to the gallery in 1969, the year before his death.

Orange and Red on Red (1957), Mark Rothko. Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Photo: © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko/ADAGP, Paris, 2023

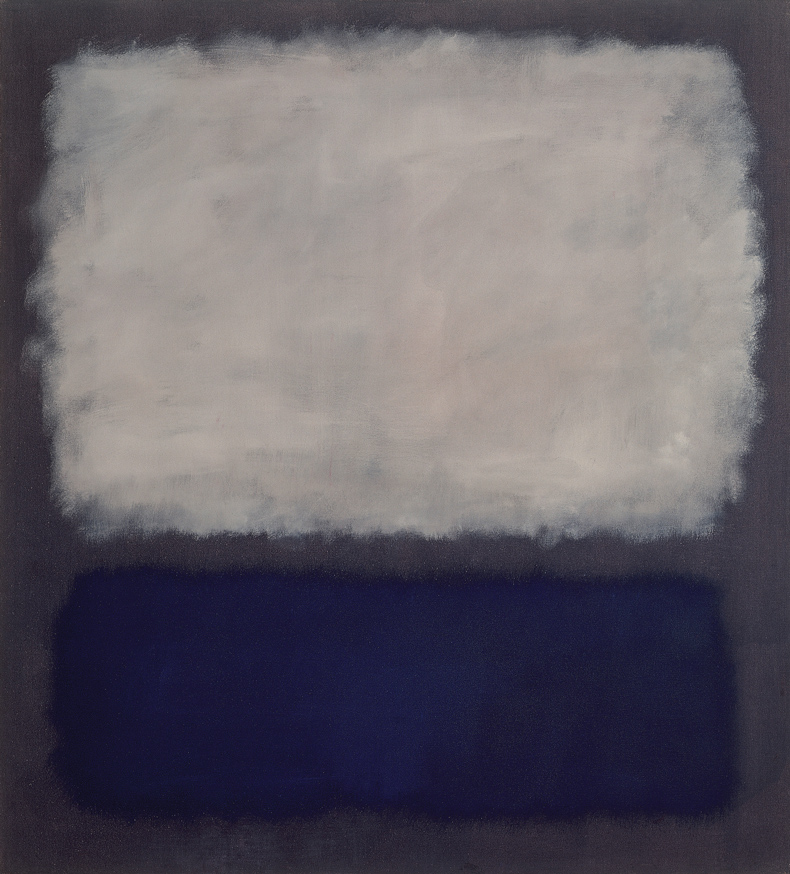

The palette of the Seagram paintings marks a move away from the glowing colours of canvases such as the Phillips Collection’s Orange and Red on Red (1957) towards the sombre ones of Rothko’s last decade – work such as the Beyeler’s Blue and Gray (1962) and, pre-eminently, the 14 near-monochrome black paintings of the Rothko Chapel in Houston (1964–67).

But the changes that took place in his art after the visits to Florence were more than just ones of colour. When Rothko had met Stanley Kunitz in 1951, the American poet had been startled by his new friend’s anti-Europeanism. ‘What I recall […] of Mark was his vehemence about the European scene, about the whole tradition of European painting beginning with the Renaissance, and his flat rejection of it,’ Kunitz said in an interview of 1983 for the Archives of American Art. ‘His saying, “We have wiped the slate clean. We start anew. A new land. We’ve got to forget what the Old Masters did” – which rather shocked me.’

Blue and Gray (1962), Mark Rothko. Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel2023. Photo: © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko/ADAGP, Paris, 2023

Now, not quite a decade later, Rothko was open in his admiration for Michelangelo, and his admission of the debt of his own work to the Renaissance master’s. It wasn’t simply the black-and-whiteness of the Laurentian ricetto that impressed him, but its interplay between art and architecture, two dimensions and three.

In the Seagram Murals, Rothko responded to this by altering the usually horizontal orientation of his paintings to a vertical one that would echo the pillars of Mies’s space. By the time of the Rothko Chapel, the boot would be on the other foot. His Franco-American patrons on the project, the collectors Dominique and John de Menil, had chosen Philip Johnson as the chapel’s architect. (Johnson had also worked with Mies on the Seagram Building.) When he and Rothko clashed over its design, the Menils quietly had him replaced.

What had happened between 1951 and 1959 to temper Rothko’s Europhobia? Here, too, foot and boot had changed place. Perhaps more than any other modern artist, Rothko is defined by his classic period – the numinous, gravid rectangles of colour that began to appear in his work in 1949 and which continued to do so until his death in 1970. One of the great strengths of the Louis Vuitton show is that it also concentrates on the earlier, pre-existent Rothko – an artist less often seen and very much less well known.

This Mark Rothko – or, rather, Markus Rothkowitz, the anglicising of his name only having taken place in 1940 – had been typical of his generation of New York painters in embracing the social realism of the Ashcan School. Rothkowitz’s particular interest was in painting the city’s metro system: thus works such as Entrance to Subway (1938), lent to the new Paris show by the artist’s daughter, Kate Rothko.

Entrance to Subway (1938), Mark Rothko. Kate Rothko Prizel and Ilya Prizel Collection

Like most of his fellows, he found it impossible to sell his work in Depression-era Manhattan. Along with Jackson Pollock and 5,000 others, Rothkowitz’s principal patron had been the US government, in the form of President Roosevelt’s Federal Art Project. Uptown gallerists such as Julien Levy and Pierre Matisse ignored local artists in favour of blue-chip – and largely Surrealist – Parisians such as Max Ernst and André Masson. The young Americans, not unnaturally, bore a grudge.

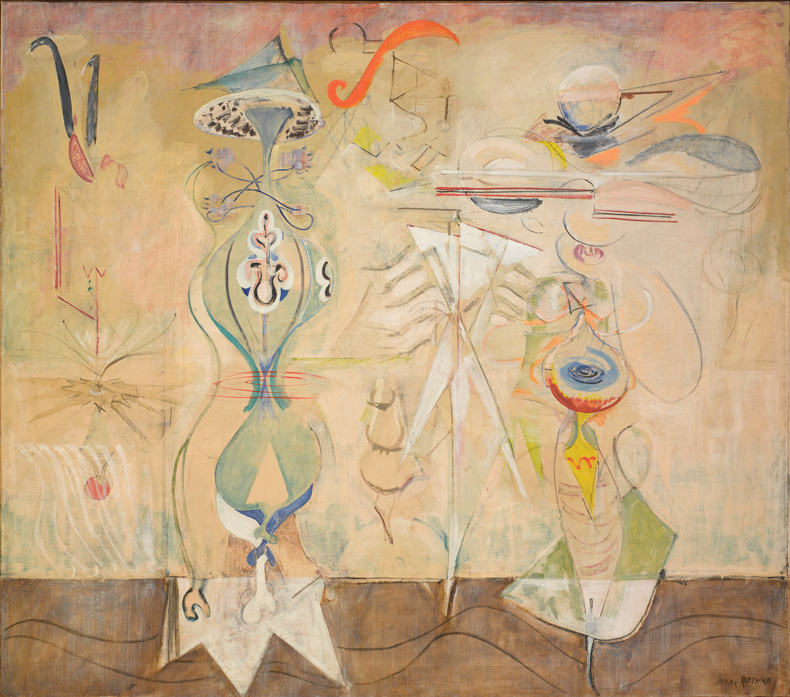

When Masson, Ernst and others arrived in New York from Nazi-occupied Paris in 1941, they were thus greeted with a mixture of resentment and fascination. The effect of the latter on Mark Rothko (as he by now was) was dramatic. Canvases such as Slow Swirl at the Edge of the Sea (1944) are a world away from the common-man literalism of Markus Rothkowitz’s subway paintings.

Slow Swirl at the Edge of the Sea (1944), Mark Rothko. Museum of Modern Art, New York

It isn’t simply that the tired commuters of the earlier work have been replaced by extraterrestrials dancing au bord de la mer. The subway pictures had been about urban isolation, a point underlined by Rothko’s use of architectural elements to break down their compositions into hermetic spaces. Now, in his Surrealist paintings, his interest is the entirely abstract one of disposing figures across a picture plane. It is a short step from Slow Swirl to the 1947 canvases that are his first wholly abstract works – Untitled (1947), lent by the artist’s son, Christopher, is one – and from there to Number 1 (1949), the first of a line from which all his later work would descend.

Which is to say that Rothko, like pretty well all of his New York coevals, had indeed been affected by the art of pre-war Paris, as the critics of Samuel Kootz’s show were quick to point out. Where those critics were wrong was in the suggestion of a continuing plagiarism. The twirling seaside Martians of Slow Swirl were, by 1944, worn-out tropes of Surrealist painting; clichés, if you like. But where they would lead Rothko had nothing to do with Surrealism or, in the end, with Paris.

He was not the only one to resent the implication of theft, or to over-compensate in rebutting it. Writing after the war, the king-making critic Clement Greenberg would insist that American painters had ‘learnt nothing from […] any of the Europeans in person or by physical proximity’. In triumphalist voice, he went on: ‘The main premises of Western art have at last migrated to the United States, along with the center of gravity of industrial production and political power.’ Jackson Pollock, too, leapt on the anti-Parisian bandwagon. ‘I don’t have to go to Europe,’ he sniffed to his friend Reuben Kadish. ‘Europe can come and see me.’

If the suggestion of European influence had still stung in 1951, by 1959 Rothko had risen above it. By now, he was internationally famous, showing not just all over Europe but everywhere from Japan to Brazil. Where he had once resented the comparison of his work with that of Masson and Ernst, the idea that he was indebted to either was by now absurd. At the end of the 1950s, he could compare himself with Michelangelo, and on equal terms.