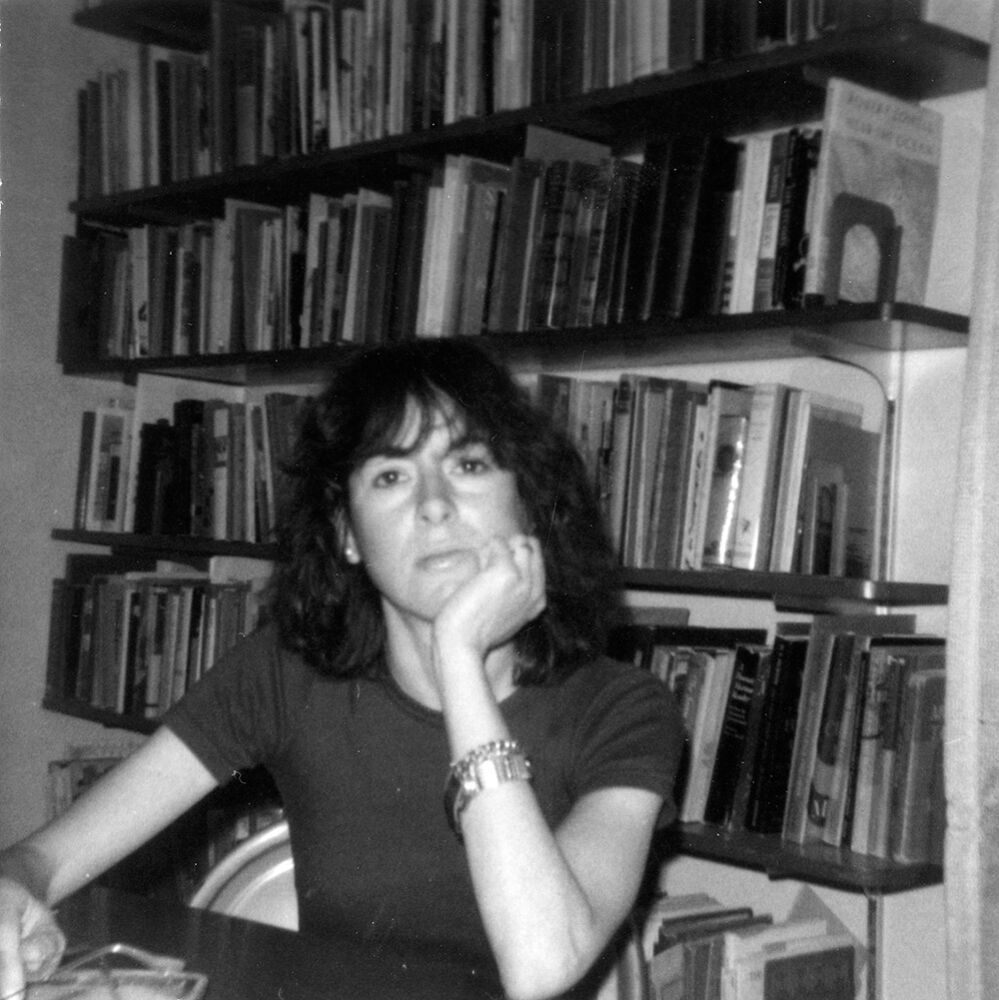

TUCSON, ARIZONA, 1978. PHOTOGRAPH BY LOIS SHELTON, © ARIZONA BOARD OF REGENTS, COURTESY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA POETRY CENTER.

In remembrance of Louise Glück, we wanted to take the special step of sharing the beginning of her Writers at Work interview from the new Winter issue, conducted by Henri Cole, on the Daily. We hope you’ll read it, along with her poems in our archive and the reflections on her life and work that we published after her death this fall. (And to read the rest of this conversation, subscribe.)

In early March of 2021, Louise Glück visited Claremont McKenna College in Southern California, where I teach. Because of COVID, she was afraid to fly on a small plane to our regional airport, so I drove her myself from Berkeley, where, for some years, she rented a house during the winters. She packed pumpernickel bagels, apples, and cheese for our six-hour road trip, and she brought CDs of Giuseppe Verdi’s opera Rigoletto, Bertolt Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera, and the songs of Jacques Brel, a Belgian master of the modern chanson. Long ago Glück and her former husband had listened to operas on road trips, but this was her first car trip in many years. She knew the musical works backward and forward, pointing out Maria Callas’s vocal strengths and clapping her hands while singing along with Brel. The magnificent almond orchards of central California had just begun to blossom and gleam beside the rolling highway. At the farmers’ market in Claremont, she bought nasturtiums and two baskets of strawberries while talking openly about her girlhood and how she’d weighed only seventy pounds at the worst moment of her anorexia. “But you love food, like a gourmand, Louise,” I said, and she replied, “All anorexics love food.” The hotel where she was staying seemed dingy, but she did not complain. Sitting on the bed cover, she propped herself up with pillows and responded to the endless emails arriving on her mobile phone.

Some months earlier, Glück had won the Nobel Prize in Literature. When the Swedish Academy phoned her quite early in the morning with the marvelous news, she was told that she had twenty-five minutes before the world would know. She immediately called her son, Noah, on the West Coast, and he was joyful after overcoming his panic at hearing the phone ring in the night. Then she called her dearest friend, Kathryn Davis, and her beloved editor, Jonathan Galassi. Reporters quickly appeared on her little dead-end street in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Soon she was exhausted from replying to the journalists’ questions, like “Why do you write so frequently about death?” Because of the lockdown, her Nobel medal was presented in the backyard of her condominium. Gray clouds blocked the sun. A light snow and frost covered the yard. The wind gusted. A small folding table was set up in the grass with an ivory cloth that made the gold medal shimmer. I watched the ceremony from Glück’s back patio, on the second floor. She wore black boots, black slacks, a black blouse, a black leather coat with big shearling lapels, and fingerless gloves. A cameraman asked her several times to pick up her medal, and she obeyed, as the wind blew her freshly cut hair across her face. The Swedish consul general explained that normally Glück would have received her medal from the king of Sweden, but that she was standing in for him. The consulate had sent a large bouquet of white amaryllis, but Glück thought they looked wrong in the austere winter scene, so they were removed from the little table. The ceremony took no longer than five minutes, and she shivered silently until she finally asked if she could go inside to warm up.

From the beginning, Glück cited the influence of Blake, Keats, Yeats, and Eliot—poets whose work “craves a listener.” For her, a poem is like a message in a shell held to an ear, confidentially communicating some universal experience: adolescent struggles, marital love, widowhood, separation, the stasis of middle age, aging, and death. There is a porous barrier between the states of life and death and between body and soul. Her signature style, which includes demotic language and a hypnotic pace of utterance, has captured the attention of generations of poets, as it did mine as a nascent poet of twenty-two. In her oeuvre, the poem of language never eclipses the poem of emotion. Like the great poets she admired, she is absorbed by “time which breeds loss, desire, the world’s beauty.”

The conversations that make up this interview mostly took place during the days of Glück’s visit two years ago, which included a rooftop seminar—with the San Gabriel Mountains as a backdrop—and a standing-room-only reading at the Marion Minor Cook Athenaeum, during which she dined with students, an experience that evidently gave her pleasure. She had no desire to undertake a cradle-to-grave interview, but she was happy to converse about her new book, teaching, and craft, and read the version of the interview that I sent her as a work in progress. After her unexpected death on Friday, October 13, 2023, I shared our pages with the Review, since there would be no further conversations.

Am I correct in thinking that you write two kinds of books—one a collection of disparate lyric poems and another that has some of the characteristics of prose, with a narrative thread?

Yes, and I seem to rotate between the modes. I also think of my books as either operating on a vertical axis, from despair to transcendence, or moving horizontally, with concerns that are more social or communal, the sort of material you might expect to show up in a novel rather than a poem. Averno (2006), for instance, is a book quintessentially on a vertical axis. And A Village Life (2009) is utterly the opposite—with different speakers coming from different times of life, living in some unspecified little seemingly Mediterranean village, though the model was Plainfield, Vermont, where I lived for many years. You make substitutions to keep yourself inventing.

In your books that move from despair to transcendence, does the divine play a role?

You could say that the divine is usually at the upper region of the vertical-axis books. In the dark lower region is human flailing—without the divine. Because I’m not a religious person, I would not use this word, divine. But I do think that there is the sense, in the upper regions, of having somehow been rescued and, at the bottom, a sense of having been abandoned.

Where did this idea of a book as one whole thing come from?

I thought about books that way from the beginning. I was writing short poems, but I wanted to build environments. I wanted to suggest an atmosphere as opposed to a subject or agenda, a meditation or quest as opposed to a stance. Of course, in the early books this isn’t obvious, though I gave great thought to the order of the poems and their implicit arc or trajectory. This attitude became more obvious in Ararat (1990). I remember that when I wrote the first poem—with all flat declarative sentences, no figurative language, no images—I thought the only way it could possibly work was as a whole book, meaning that the flat language had to have, behind and around it, a world.

What about Faithful and Virtuous Night (2014)?

The adventure of Faithful and Virtuous Night, which moves along a horizontal axis, was twofold. First, writing a very, very long poem, which has to do with—I always deplore this as a subject matter—art and the making of art, though the speaker begins as a baby, and I think this gives it a certain kind of originality. The other thing I discovered was the prose poem. I had never understood it as a form until I read Mark Strand’s Almost Invisible, which galvanized me. I thought his were the most amazing prose poems I had read in a long time, which didn’t suggest that I would be able to write them myself. My book was almost done, but it felt leaden, and it needed something else. A close friend said, “Why don’t you read Kafka’s short shorts, which are like prose poems?” I had read Kafka’s short shorts, but I follow advice when it’s given by someone I have high respect for. And when I read them again, I thought, Oh, I don’t think these are that good—I could do this. So I did, and it was so much fun. And then for a while I forgot how to write lines, so that was its own little calamity …

Would you say more about your friends and how they influence your work?

Most of my books are dedicated to my friends. My friends are the center of my life. They are crucial. I change my life to be sure that I see them. They’re all quite different people. I would be impoverished without them. Recently, I bought a small house in Vermont, where my oldest friends still are. My dearest friend now lives two minutes away. For a very long time, I lived in Cambridge and showed her everything I wrote though she lived elsewhere, but now another form of the friendship has been resumed, and it seems that it was waiting to be resumed at any time when it could be. My friendships with people in different cities seem to be like that. There can be a distance in time and also a geographical distance, but when I see them again, it’s as though no time has passed. I mean, much time has passed, many things have changed, but you resume the conversation about what’s going on in the same way as before. And that is the most extraordinary ongoing fact of my life.

“Winter Recipes from the Collective,” the title poem of your recent book, makes me wonder whether you ever lived in a collective or ashram or commune. Also, did you write the sections of this long poem in the order in which they appear?

I’ve never lived in a collective or ashram or commune. Plainfield was the closest—severe weather would turn the village into something like a collective, in that there was a great deal of pooling of resources and watching over the needs of others and cooperating to survive the ordeal of the very long winters, scarily less long now. Everything in the poem is made-up—the collective, the moss-collecting and fermenting, the bonsai cultivation, and the Chinese master. The sections were written at long intervals, with other things in between, over probably a few years of not writing much. The first section was definitely first.

Do you write every day? Are your poems written long after lived experience?

I don’t have a regular writing protocol or schedule. I’ve found that too anxiety-producing, because there were so many days I sat in front of the typewriter and a piece of white paper and wrote nothing. It was an annihilating experience. So I write when I begin to have phrases in my head—I jot them down, and then, after a while, I go to the typewriter.

I don’t think I write through transition periods. What happens to me is that something stops, something ends, something is brought to a closure. Then I have nothing—I’ve used up whatever it is that I had and must wait for the well to fill up again. That’s what you tell yourself, but it doesn’t feel like a sanguine experience of sitting quietly while the well fills up. It seems like an experience of desolation, loss, even a kind of panic. The thing you would wish to be doing, you can’t do. I’ve been through a lot of those periods, and what seems to happen, or what has happened in the past, is that after a year or two, or whatever the duration, another sound emerges—and it really is another sound. It’s another way of thinking about a poem or making a poem, a different kind of speech to use, from the Delphic to the demotic. Suddenly I’ll hear a line—you can’t hear this yourself when I read, because my voice tends to pasteurize everything—suddenly I’ll realize that I’m being sent some sort of message, a new path, and I try it on. That’s how things change for me—it’s never that I work my way through it. I have friends, great poets, who seem to make extraordinary use of a daily ritualized writing practice, but for me that doesn’t work at all.

May I ask about “Song,” the beautiful closing poem in Winter Recipes from the Collective (2021)? Is the “you” in the poem you, Louise?

No. The “you” changes in this book—sometimes the you is a sister, a friend, a companion, a person who is on the journey with the speaker. The you in “Song” is slightly different from the friend-companion-sister figure—this is you, the reader, or whoever is listening to me. In the dream that was the basis for the poem, I think the you was a good friend of mine. We had been talking about ceramics. I love ceramics.

In your dream, was the ceramist really named Leo Cruz?

Yes, and I don’t know anyone by that name. I don’t know anyone named Leo, and I don’t know anyone named Cruz, so it was an invention. That’s what I liked about the line. You couldn’t find him. He’s not in the world. I mean, there may be forty-five hundred of them, but this one who makes porcelain in the desert, he’s not there. He’s part of a dream. He stands for the fact that something in the desert is alive.

What is it about ceramics that you love?

I like objects that have utility. I like beautiful things that have a use. I’m a very domestic person. I like to cook, so I like table service, which inevitably leads to ceramics of some kind. I also like flower vases and objects that have no use, but mainly it’s the combination of beauty and usefulness. Also, I love old Japanese ceramics. The idea that something valuable is fragile is also attractive to me.

When I first moved to Vermont, in my late twenties, a long time ago, Goddard College was flourishing. I had a one-semester appointment—that’s why I moved there—and it was my first job teaching a poetry workshop. Goddard had a naked dorm and the class was held there, which didn’t mean my students were naked, but that the students who lived there were. When my class met, we would keep our clothes on, but it was weird to see these naked bodies going back and forth, not all of them fabulously beautiful, I might add, though they were all young. A lot of interesting people in that period were making remarkable ceramic art, and there was a great teacher, so I would hang out at the pottery studio, and I learned how to use the wheel—not expertly, but I loved sitting at the wheel and feeling the clay. I loved the way you would hold your hands steady and a shape would form. I especially loved doing raku. Do you know what raku is?

Does it have a crackly glaze?

You use a certain kind of glazing that’s more porous than normal glazes. When you pull the pot out of the kiln, you might throw it outside onto something that will affect the way the glaze plays on and imprints the object. There is a feeling of randomness. It was so exciting to pull this hot thing out of the kiln and walk outside and throw it into the snow. Then you’d have to find it. Sometimes they were horrible-looking—little gaseous-looking lumps. But it was always fun, and sometimes they were quite beautiful. I mean other people’s were quite beautiful—mine were rarely beautiful. I did keep one somewhere, or I tried to keep one.

Do you prefer to write from your dreams and unconscious, as you do in “Song,” or to make things up? How do you choose?

It’s not choose. Something presents itself and you have an instinct for what you can use, the way a bird building a nest knows, Oh, I need a little piece of red ribbon there, and then goes out searching for red ribbon, or the bird might not know that but see the red ribbon and think, Hmm, that has my name on it. You use what you come across, and you come across your dreams with regularity. I don’t sit at my desk and think, Now I will use something from my recent dream. It’s more like I wake up with a line and I write it down and I look at it, and it’s mysterious because the dream is mysterious—I don’t know what it means. Then I invent a context for it. Or I fail.