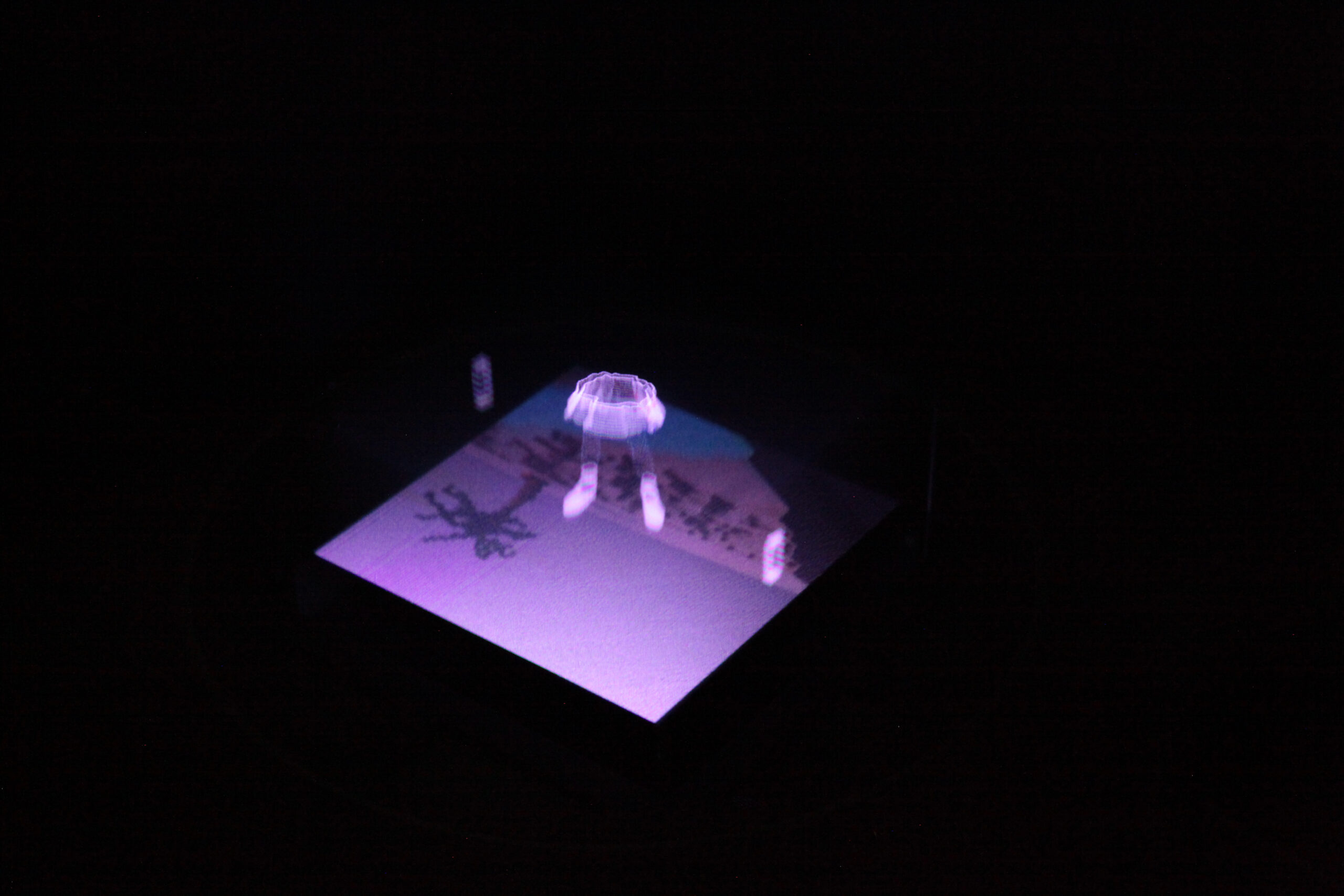

David Levine, Dissolution. Courtesy of the artist.

Currently on display at the Museum of the Moving Image is a dollhouse-size hologram that looks straight from the future. David Levine’s Dissolution, on view through March 1, is a sculptural, three-dimensional film: a cube-shaped space projected from below through a vibrating glass plate that hums and whirs like an analog projector. A twenty-minute monologue runs on a loop, voiced by a tired and paranoid human named Vox (Laine Rettmer), who has been trapped inside this machine and turned into a work of art. As Vox bemoans her predicament—existence as both human and artwork—disconnected images come and go: an octopus mining for crypto, fragments of classical sculpture, and a tortoise with a jewel-encrusted shell (the last an homage to Joris-Karl Huysmans’s Against Nature). The artwork contorts our own bodies, too; I found myself twisting around to see the object from every angle, hypnotized by its miniature beauty and disoriented by its dizzying colors and sounds. A suspicion toward beauty might be the subject of Dissolution, a piece influenced by Brechtian principles of estrangement and alienation: the small, buzzing machine pulls us in only for Vox to spit us back out.

—Elinor Hitt, reader

The work of history is slow, even for the merciless flow of commercial recordings, as is the influence of most compilation albums. Nobody is ever fiending for a compilation—not really. But let them soak, and they can reshape the past or propose a new future by clarifying the present. Wanna Buy a Bridge? (1980) and Platinum Breakz (1996) spring to mind: the former, put together by Rough Trade, definitively expanded the genre of post-punk; the latter, the first in a series released by Metalheadz, confirmed that drum and bass could channel twenty years of Black music into a single convulsive moment. Time Is Away have done something similar with Searchlight Moonbeam, a “narrative compilation” whose contents span almost ninety years of song and suggest a robust team of slippery dreamers.

Ten years ago, the historian Elaine Tierney and the bookseller Jack Rollo began doing a show for their friends at NTS Radio as Time Is Away, a monthly program that combines archival speech and sound into something like an hour-long essay. It undersells their archive to say that it is one of the most valuable free resources on the web. I first encountered the show through their John Berger episode in January 2017, right after Berger’s death—a careful edit of snippets from Berger’s television and radio appearances laid over a bed of peaceful keyboards and voices and guitars. Though its source materials aren’t exactly obscure, the episode feels new, like a scripted audio documentary or a unified narrative drawn from undiscovered tapes. Rollo and Tierney’s edits make the popular mysterious. When they play a song I know, I am convinced I do not.

If you go through their archive, back to 2014, you will find “Land: A Common Treasury,” a weaving-together of commentary by Derek Jarman and others about the conceptual flexibility of land. There is also “Docklands,” from 2018, which quotes parties for and against the development of East London. An episode from 2023, “The Wildgoose Memorial Library,” is the first part of a longer engagement with the London collector Jane Wildgoose, the designer of the Hellraiser costumes and an archivist of extreme and unusual objects. Time Is Away recall the authority and range of Guy Davenport; like his writing, their mixes are always surprising, either in reference or structure.

The duo’s thoughtful methodology is mirrored by music that rarely slashes or points. Time Is Away don’t play songs that dream of blocking out the sun. They have, instead, managed to find a whole island of quiet records, inaccessible to anybody else (it seems) but bountiful enough to supply two radio shows (Rollo does The Early Bird Show for NTS on Fridays) and a growing stack of compilation albums. Tierney and Rollo put together their first official compilation, Ballads, two years ago, for the Australian label A Colourful Storm; Searchlight Moonbeam, their second, was made for a different label from Melbourne called Efficient Space. The years of record releases on the compilations range from 1934 (a voice and piano rendering of Schubert) to 2022 (O. G. Jigg’s “Jesus Is My Jam,” among others). Searchlight Moonbeam starts with “No One Around to Hear It,” a song that was recorded by Bo Harwood and used in the 1976 John Cassavetes film The Killing of a Chinese Bookie but never released until Harwood posted it to his own website a few years ago. Harwood sounds like a slightly calmer Robert Plant in ballad mode. This segues into “Rainwater,” a 1996 recording by the Taiwanese singer Chen Ming-Chang. There’s a cover of Public Image Ltd’s “Poptones” (1987) by Simon Fisher Turner that turns the murderous dub of the original into a candy-land lament, and Soft Location’s “Let the Moon Get Into It,” which could be a Sinead O’Connor demo. The cohort proposed by Searchlight Moonbeam exhibits a kind of steel-plated saudade, an acceptance of idiosyncrasy, and a love of uneven lines. These musicians feel like members of an ancient diaspora, a benevolent community whose members Rollo and Tierney have dedicated their lives to finding, documenting, and celebrating.

—Sasha Frere-Jones

During the many hours I spent with the playwright Lynn Nottage for her interview in the recent Fall issue of the Review, I was reminded that she is a macro/micro artist. Her plays weave global ideas into the intimate and delicate dance of being human. I adore these kinds of artists—folks like Nottage, the poet Pat Parker, the composer Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou, and the dancer nora chipaumire. They inspire me to reach up and out in my own writing. The photography-based artist Tawny Chatmon is another such artist. Her portrait Reigning, which I saw in her solo exhibition Inheritance at Fotografiska in New York, features a Black girl, relaxed and present, gazing into the viewer’s eyes. Chatmon hand-embellished the subject’s hair and torso using acrylic paint and 24-karat gold leaf, giving the piece a profound three-dimensional beauty. From a distance, the portrait served as a window, a mirror, a timeless moment steeped in the now. As I stepped closer, I saw the intimate and detailed designs—hypnotic, playful, intentional. The gold is a celebration and a reverence that resonates. This skill displayed in Chatmon’s piece, this joy, this micro/macro, is what I strive for when I write for the stage. Her work reminds me that the page, the canvas, the frame are all opportunities to reach for beauty, to see the viewer, and also to be seen.

—Christina Anderson