Wagner doesn’t mean what it used to. Google “Wagner” today and you’ll be up to speed with the Russian private army’s exploits well before you read about Hitler’s favourite composer. In fact “Wagner” is as likely to suggest the 2010 X Factor contestant as the maverick German genius who, after handing out grenades on the Dresden barricades in 1848, sought to liberate opera from its Italianate shackles by means of Gesamtkunstwerk – or “total works of art” – and thereby free humans from lives of spiritless toil and demeaning leisure.

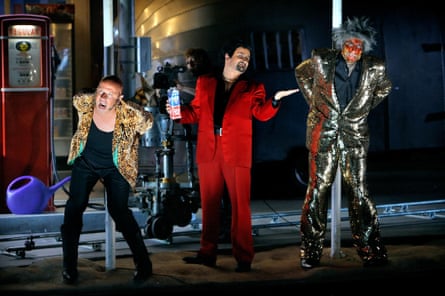

Chief among Wagner’s total works of art is the 15-hour operatic tetralogy Der Ring des Nibelungen, which the Royal Opera House begins to roll out next week. The first instalment, Das Rheingold, will be conducted by Antonio Pappano in his final season as Covent Garden’s music director, and directed by self-described “gay Jewish kangaroo” and sometime hater of Wagner, Barrie Kosky.

There will be, as usual, gods, flying horses, dragons, dwarves, giants, magic helmets, sword-wielding men, babies, magic potions, incest, unpleasant family dramas, marital strife, betrayal and – let’s not forget – after about 14 hours and 40 minutes (spoiler alert), an apocalypse that exterminates the gods.

But why bother? Wagner has never felt more culturally marginal than today, even though, paradoxically, many leading cultural franchises, from Lord of the Rings to Star Wars to Game of Thrones, are unthinkable without his influence. On the face of it, 2023 needs nothing so little as bombastic white-male-supremacist art composed by an antisemitic megalomaniac whom even one-time superfan Nietzsche came to see as a kind of cultural Covid. “Is Wagner a human being at all?” Nietzsche asked. “Is he not rather a disease? He contaminates everything he touches – he has made music sick.”

London has already nixed one Ring cycle this year. In January the English National Opera cancelled Siegfried (the Ring’s third part) over funding worries. Perhaps, particularly in a cost-of-living crisis, we need not go to see multimillion-pound Ring cycles with hydraulic sets and mechanical dragons. Instead click on YouTube, where you can watch the drama played briefly out by Lego figurines. Or attend a Ring cycle with a postcolonial twist staged in a Putney church by small London-based arts collective Gafa, run by singers of Samoan heritage. Or maybe someone can ask maverick opera director Peter Sellars to update the puppet Ring cycle he did as an undergraduate?

Wagner at least thought he was issuing a deep, unified statement of cultural truths that could change how we live. “He felt there had to be some kind of drastic step taken in order to revolutionise the way people lived and their demands on life,” Wagner scholar Michael Tanner said. “Otherwise they would just sink to a level where they didn’t mind the fact that they were living so much less fully than they could do.”

Playwright George Bernard Shaw interpreted the Ring cycle as an allegory of the collapse of capitalism. But it is endlessly interpretable. It can serve not just as Marxist tract but as a Third Reich allegory; a sado-masochistic indictment of the have-yachts in the posh seats, or a Buddhist-inflected music drama in which the high body count suggests the death of the ego that Wagner thought, in line with his beloved philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, was desirable.

Richard Jones, director of two-fourths of ENO’s current Ring, favours something like the last account: “Ultimately it’s about the idea of self-renunciation. It’s like great Greek drama. Since it was first performed in 1876, there has never been a period when it wasn’t germane to the contemporary world,” he told the Guardian when his cycle opened in 2021.

Certainly, Wagner supposed his music drama would offer quasi-religious experience in the ancient Greek manner. “His idea was that a sufficiently potent new art form, such as he was perhaps uniquely able to write, would, by being experienced, communally change people’s consciousness,” said Tanner. “You would emerge a different person.” Wagner even built a temple to this cult in the form of Bayreuth’s opera house.

From what can be gleaned from the creatives (who may have signed NDAs threatening impaling by Wotan’s spear if they blab production details), Kosky has different ideas. “There’s a strong ecological theme,’ says Pappano. “Barrie’s worked through the antisemitism in the previous Ring cycle he staged. This will be quite different.” In Hanover in 2009, Kosky made Mime (the duplicitous brother of Alberich, the dwarf who steals the ring) personify what Wagner wrote about Jews and Jewish music, which the composer described as a “sense-and-sound-confounding gurgle, yodel and cackle.”

Baritone Christopher Maltman, who sings chief of the gods Wotan in the new production, argues that the Ring’s fundamental question is: what does power create? “In Wotan’s case, his quest ultimately is to seize the Earth for dominion.” Maltman tells me Kosky’s conceit is to conceive the drama as the dream of the Earth Mother, Erda, who gave birth to our home 4.6bn years ago and, when not bearing Wotan’s bastards, watched her first child’s despoliation.

Whatever Pappano and Kosky deliver, it’s bound to be very different from what audiences saw on 9 August 1876. The Guardian correspondent in Bayreuth described how at the premiere, control freak Wagner sat in the wings. “Suddenly he would shuffle across the stage, gesticulate violently to put more force into the orchestra, or rush up to a singer in the midst of his or her part and say, in a light sharp voice: “No, no, no; not so; sing it so –” He would then sing the part as it should be, or throw the necessary dramatic fire into the acting.

“The delighted audience sat in silence, and as they streamed out of the theatre on to the terrace and into the beer-room in their festal dress, the only word heard was ‘Herrlich’.” That means glorious.

One hundred years later, the Bayreuth reception for the Jahrhundert Ring cycle was less enthusiastic. Patrice Chéreau and Pierre Boulez essentially targeted the bourgeois ticket holders, which, you have to admit, is a bold move. The production was booed and caused a near riot.

Wagner might have liked that. As Tanner wrote in his 2002 book Wagner, Das Rheingold depicts “a primal world which is corrupt from the start, thus producing something at odds with the central myth of western culture. Power and libido are what animates it.” If the Ring cycle is the pinnacle of bombastic patriarchal dead white supremacist art – and you will struggle to find many persons of colour or women who have directed the Ring, though some of its greatest singers have been black and/or female – it’s not one that flatters its demographic.

The Chéreau-Boulez Ring is now regarded as a classic. Robert Lepage’s 2010 New York production replaced it as a benchmark for the kind of interpretive travesty that Wagnerites such as the late social critic Roger Scruton regard as a systematic betrayal of the composer’s sacred text. “Pound for pound, ton for ton, it is the most witless and wasteful production in modern operatic history,” raged Alex Ross in the New Yorker.

The problem was the centrepiece of LePage’s set, a rack of 24 planks built out of fibreglass-covered aluminium that rose and fell powered by hydraulics that revolved through 360 degrees on a specially reinforced stage. Even as late as the 2019 revival, the contraption still squeaked above any passing Brünnhildes. Perhaps the squeaking machinery was ironic commentary: capitalist mechanisation had ruined us, and now it was ruining opera.

Not to be outdone, the 2010 Los Angeles Ring cycle had singers briefing against director Achim Freyer’s production even before it opened. Tenor John Treleaven, who sang Siegfried, and soprano Linda Watson (Brünnhilde) called the staging physically unsafe – “the most dangerous I’ve been on in my entire career,” said Watson. The problem was the angled stage that compelled singers to perform as if on the side of a slope. Hitchcock called his actors cattle; perhaps Freyer thought his singers were mountain goats.

As if singing Wagner wasn’t hard enough already. Maltman, at 53, feels only now is his voice mature enough for the role, which he describes as more physically demanding than Hamlet or Lear. He learned from previous Wotans, particularly the great John Tomlinson. “He helped me not just understand how to sing the role but how to interpret it.”

“You certainly need to bring your A-game,” says Pappano. “Phone it in at your peril.”

Back to the plot: having cursed love and stolen the gold which he forges into the ring, Alberich is tricked out of it by Wotan who needs cash sharpish to pay for his new Valhalla palace. But Wotan immediately loses it to two giants. We’ve all done that, right? Wotan attempts to get it back while noting the tragicomic consequences of having filled the cosmos with bastard children, such as the twins Sieglinde and Siegmund who, in the opening of the second opera, Die Walküre, have an incestuous relationship that results in Siegfried, the hero who in the third opera in the tetralogy kills the giant Fafner (in the form of a dragon) and retrieves the ring. In the last opera, Götterdämmerung, Siegfried (Wotan’s grandson) is married to Brünnhilde (Wotan’s daughter) but despite having a magic sword is stabbed in the back by Alberich’s son. Brünnhilde, after denouncing the gods (including Dad), takes the ring from her dead husband and returns it to the Rhinemaidens. Then, like some operatic approximation of Thelma and Louise, she jumps aboard her faithful steed Grane and rides into Siegfreid’s flaming funeral pyre. The Rhine overflows, consuming gods and Valhalla in water and flames.

Can we expect boos, riots, Walkyries in traction and backstage feuds from Covent Garden this September? There is hope. Announcing the production earlier this year, Kosky stressed that this is a family drama – not Dynasty with horned helmets, but more like Aeschylus’s Agamemnon, Wagner’s favourite play. “In this appalling story of the House of Atreus, the Greeks created a microcosm of us,” says Kosky, and for him the Ring’s extended family of gods and mortal offspring is the same.

The Ring is an “existential drama”, says Kosky. Wagner asks the big questions. “What are we doing here? Who are we? It contains reality, it contains three-dimensional characters [but] it’s very important that the Ring is a metaphorical poetic dream world.” How excellent if Kosky, rather than making distracting pieces of conspicuous consumption for punters with more money than taste, made something that, like the magic sword of Nothung, cut through the guff and gave us a Ring cycle that told us something important about how we live now.