Mr. Paxton’s dance vocabulary wasn’t always basic. For his 1963 work “Afternoon,” he taught Ms. Rainer and other dancers some choreography filled with tricky balances, in the Cunningham vein, but he had them perform it on the uneven terrain of a forest in New Jersey. Ms. Rainer later characterized Mr. Paxton as her “favorite wily choreographer.”

In 1970, Mr. Paxton, Ms. Rainer and several other members of Judson Dance Theater started performing together as the leaderless collective Grand Union. The group’s shows were improvisational, anarchic, free-associative.

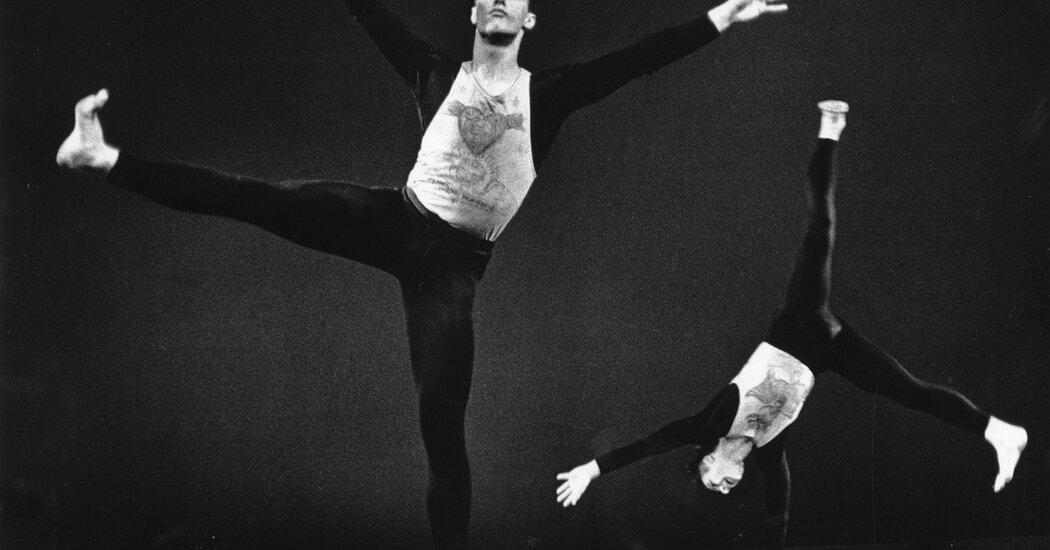

For Mr. Paxton, Grand Union was a laboratory in the possibilities of form and performance. One possibility that he explored further grew into what he called contact improvisation, a duet form in which participants give and take each other’s weight — tumbling, lifting, carrying, falling. The goal, Mr. Paxton explained in 1975 in the journal The Drama Review, was to find the “easiest pathways available to their mutually moving masses.”

Contact improvisation can look like gentle wrestling, but it can also be full of surprises, riding the edge of disorientation and risk. (Mr. Paxton had been studying aikido.) It was “a form arising from us rather than imposed on us,” Mr. Paxton told Dance Magazine. “It’s a game that takes two people to win, so it doesn’t create losers.”

Although contact improv was sometimes practiced in front of an audience, Mr. Paxton intended it as both a form of artistic experimentation and a meditative mode of heightening perception and nonverbal communication. For many people, it became a way of life, with a journal (Contact Quarterly) and conferences, classes and jam sessions in many countries. In the mid-1980s, Mr. Paxton was not pleased to learn that some people had come to see it as a recreational sport. (“In just 15 years,” he said, “it had gone from an art exploration and a performance thing to a recreation, a dating game.”)

But he moved on to other explorations. From 1986 to 1992, he performed “Goldberg Variations,” a series of intricate improvisations to a Glenn Gould recording of that Bach composition. Beginning in 1986, he developed what he called “material for the spine,” a system focusing on the muscles and sensations of the back, aiming — as he put it in an instructional video — “to bring the light of consciousness to the dark side of the body.”