In the late 1970s, in Montreal, photography students were obsessed with getting deep blacks — “max black” — in our prints, squeezing the full range of tones out of our black-and-white photo paper. Knowing that light meters were designed to average a scene out to gray, we recalibrated ours to make the shadows in our shots as darkly lush as an Ansel Adams moonrise.

Few of us realized there might be more to blackness than a lack of light. We didn’t understand that in the right hands, the deep, deep blacks might speak to far more than a darkroom technique — to issues of race and segregation.

Four hundred miles south of us, in New York, Ray Francis was printing shots that had the bold shadows we were striving for. Thirty-two of his prints are on view now in “Waiting to Be Seen: Illuminating the Photographs of Ray Francis,” at the Bruce Silverstein gallery in Chelsea, a posthumous show that is Francis’s first solo presentation. He died in 2006, at 69.

In 1963, he helped found the Kamoinge Workshop in New York, a collective dedicated to “photography’s power as an independent art form that depicts Black communities,” according to the Workshop, which is furthering its mission today. The photos on view at Silverstein suggest that, in the circle of Kamoinge, depicting Black people was likely to involve thinking about black tones in a print.

Francis’s images, with their reflections on race, seem to get a special energy and power because of their links to art photography that cared so deeply about the darkness in a black-and-white print.

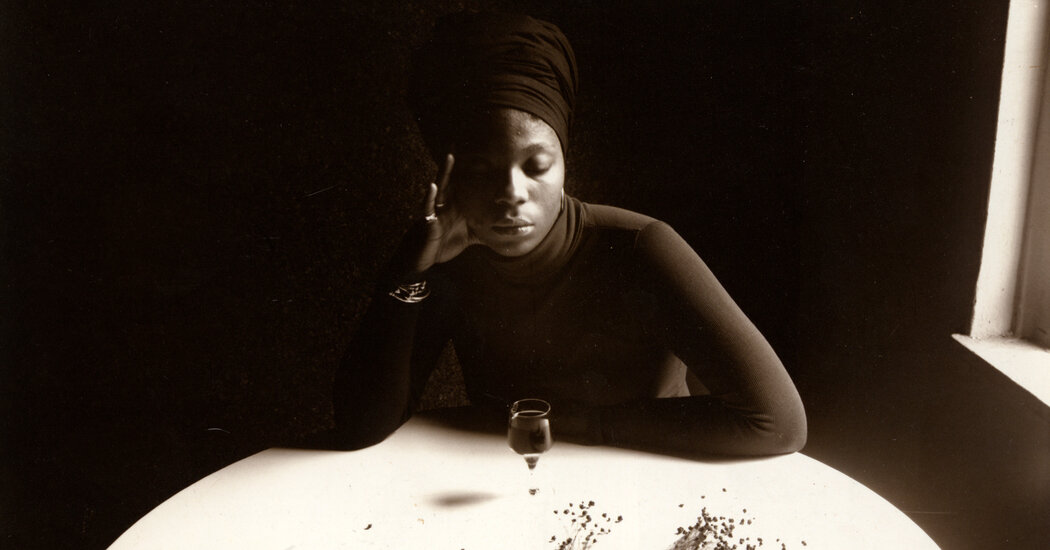

In his portraits of African Americans, faces are often lit so one side is bright and the other falls off into darkness. He’s hardly the only photographer to use that split lighting, but what’s striking is that he lets the dark side of his faces descend into almost pure black, without the range of velvety tones that “fine art” photography was keen on in his day. That wasn’t because he didn’t know how to achieve that range: His show includes still lifes whose shadows are as subtle as could be; the gallery told me Francis was known in the Kamoinge for his technical expertise. Allowing shadows to fade to pure black seems like a way to assert the role that race played in his subjects’ lives, and also to celebrate it.

Other shots by Francis seem to speak to the same issues, but this time by looking deep into those shadows. A view of a woman’s naked back runs through every shade of near lightlessness, from midnight to charcoal to ebony. But in achieving them, Francis was working against a technology that, used unthinkingly, would have changed her skin tone into a middling gray — the skin tone, say, of a white model with a nice tan. (It’s well known that color film, which Francis does not seem to have used, was once calibrated to flatter Caucasian skin.) Francis would have known that, for more than a century before he was born, in 1937, photographic technique — lighting and exposure, in the studio, and then developing and printing and even retouching, in the darkroom — had deliberately been used to lighten Black complexions, and negate them. Hard not to read the lush blacks in his naked Black back as a criticism of that.

Beginning at least in the 1980s, other artists of color — Kerry James Marshall, Kara Walker, Glenn Ligon — have also made important work about how black tones, on a surface, relate to the idea of a Black race, and that has been much studied among curators and academics. But Francis was working in the quite particular context of what was then called, and hived off as, “fine art photography” — a world ruled by the likes of Adams, Minor White and Edward Weston, none of whom have mattered much within the world of so-called serious contemporary art where Marshall and his peers play their part. Working in that context, however, let Francis make images of African Americans where shadows get added meaning.

And once you’re thinking in those terms, even the black tones in his still lifes start to have a social charge. One still life foregrounds a glass of red wine, which turns into “black” wine in Francis’s black-and-white shot. That glass and its wine takes up just the space that a head would in a close-up portrait; it seems a surrogate for a face. A dark wine bottle, like the one featured as a prop in several Francis portraits, is glimpsed through the stem of his glass; it reads as the body of a Black onlooker, maybe even as an avatar of Francis himself as he takes the shot.

If expertise in achieving black tones was a road to success in the fine-art photography of Francis’s era, invoking the Blackness of race was almost sure to leave you sidelined. Francis had to make his living teaching and doing commercial work, which left him little time to make art. The gallery believes that the prints in this show make up the vast majority of Francis’s surviving work as a fine artist. In his final decade, when photography had at last begun to care, Francis’s production was limited by the diabetes that cost him both legs.

You’ll still sometimes hear people say that a work of art should be judged only on what you can see right on its surface. This show proves that, on the contrary, to reap a work’s meanings you need to know all about who made it, and when. To understand the best photos in the Silverstein show, you need to know about the shadows in an Ansel Adams print — and the Black community Ray Francis set out to honor.

Waiting to Be Seen: Illuminating the Photographs of Ray Francis

Through March 23, Bruce Silverstein gallery, 529 West 20th Street, Manhattan; 212-627-3930, brucesilverstein.com.