On a dark, featureless stage in Amsterdam, a soon-to-be-crucified Jesus Christ laments his predicament while sporting a shimmery tank-top and gray New Balance sneakers. His followers, gathered around him, look like they have raided an Urban Outfitters store sometime around 2012.

By stark contrast, his persecutors, led by King Herod and Pontius Pilate, wear severe white, floor-length robes and black coats. In an earsplitting falsetto, Jesus reproaches his father, God, for having put him in this position. As well he might.

This revival of “Jesus Christ Superstar,” Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice’s kitschy 1971 musical about the last few days of Jesus’s life, is directed by the Belgian auteur Ivo van Hove. It’s an odd match.

Van Hove has built his reputation on aesthetically striking, often psychologically intense re-imaginings of well-known works — including canonical plays (“Hedda Gabler” and a riveting “A View from the Bridge”); golden-age Hollywood movies (“All About Eve”); and contemporary fiction (“Who Killed My Father” and “A Little Life”). And though his range is wide, there has always been intellectual ambition in his choice of subject matter: a serious interest in the poetics of human tragedy.

So it’s hard to fathom what drew him to “Jesus Christ Superstar,” a musical whose notoriety has been largely premised on the incongruity between its somber subject matter and its disarmingly peppy, down-with-the-kids lingo. At times, the lyrics also have rather forced, knowingly silly rhymes, such as when Jesus implores God to “show me now that I would not be killed in vain? Show me just a little of your omnipresent brain.” To transmute such willful inelegance into high art would be a miracle indeed.

The productions runs at the DeLaMar Theater through Feb. 18, with a cast that is almost entirely Dutch, delivering songs in smooth English. Magtel de Laat gives an impressive vocal performance as the prostitute Mary Magdalen, whose touchy-feely tenderness toward J.C. offended the sensibilities of Christian conservatives when the musical first appeared in the 1970s.

With his long locks, wide-neck T-shirt and gray jeans, Lucas Hamming’s Judas Iscariot, who narrates the story, has something of the beleaguered British comedian Russell Brand about him. It’s a strong look for the part.

In the title role, the Surinamese singer Jeangu Macrooy has an ethereal, deer-in-the-headlights vulnerability that is a little hard to square with the messiah’s much-vaunted charisma: His Jesus comes across more like the fey frontman of a mid-ranking indie band than a rabble-rousing revolutionary. When both Mary and Judas muse aloud on the secret of his magnetism in “I Don’t Know How to Love Him” (“I don’t see why he moves me / He’s a man, he’s just a man!”), it feels all too real.

In fairness, however, the weakness here is the material, not the performers. Aside from one pivotal moment — the betrayal of Jesus by Judas — there are few twists and turns. It’s mostly exposition and wallowing. The show’s straightforward plot trajectory is neatly summed up in a dismal couplet in the lament “Gethsemane,” in which Jesus finally resigns himself to his fate: “Then, I was inspired / Now I’m sad and tired.”

The music (arranged by Ad van Dijk) is a competent reworking of Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice’s original songs — a blend of classic rock riffs and poignant power ballads — but there isn’t much variety. The timbre is either very up or very down, with only the occasional curveball. A chipper, upbeat number plays during a scene in which Jesus is violently tormented by his captors, and even briefly waterboarded. It’s darkly edgy, reminiscent of Quentin Tarantino’s ’90s heyday.

The sung-through format, together with van Hove’s fidelity to Rice’s lyric sheet, have a fatally constraining effect. Short of rewriting the thing, the director must rely almost entirely on audiovisual effects — the austere set and occasionally spectacular lighting effects are by Jan Versweyveld — in order to turn it into something other than bubble gum theater. Unsurprisingly, van Hove only half succeeds.

During one scene, in which a guilt-ridden Judas suffers paroxysms of remorse, the lights blink on and off at jarringly sporadic intervals to heighten our sense of his psychological turmoil. But other embellishments merely nod to an idea of avant-garde experimentalism without actually enhancing the experience: When the cast hands out wine bottles and glasses to audience members during the Last Supper, it’s not immersive, it’s just awkward.

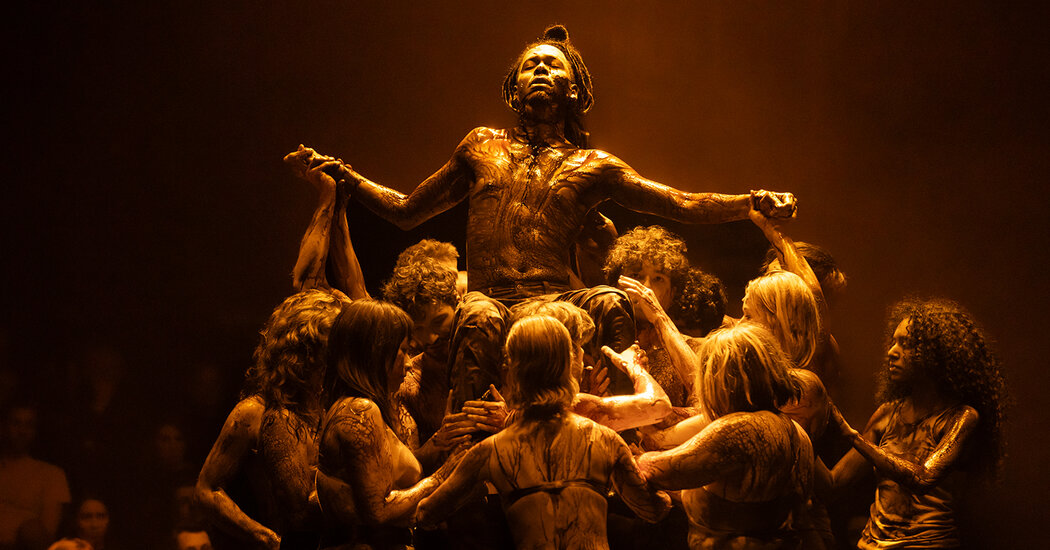

The production’s strengths and weaknesses are succinctly represented in its closing scene. “Jesus Christ Superstar” ends with a bloody Jesus, arms outstretched in a crucifixion pose, propped up by his entourage and elevated under a shaft of deep orange light that very gradually brightens — evocative of sunsets and sunrises, endings and beginnings — before he is drenched in a fine, mist-like rain dispensed from a sprinkler system. It’s a stunning image, beautifully rendered.

Moments earlier, however, members of the supporting cast were smearing blood over each other’s torsos in a heavy-handed metaphor for their moral complicity in Jesus’s demise. It felt overwrought and trite, like a sophomore art-school project. Van Hove has a thing for bloody imagery: His Hedda Gabler was famously doused with tomato juice by the lascivious Judge Brack; “A View from the Bridge” ends with its cast being symbolically drenched in blood. It worked well then, but the trick has worn thin.

People flocked to see “Jesus Christ Superstar” in the ’70s and ’80s, and, writing in The Times in 1993, Frank Rich suggested that such rock operas were musical theater’s clumsy attempt to win back the audience base it had lost to rock ‘n’ roll.

Today, guitar music itself is arguably as much a fixture of the nostalgia circuit as vaudeville, and so to revive a rock opera in 2023 is to heap kitsch upon kitsch. The only way to make it work — if you must insist on doing it — would seem to by ramping up the humor and exuberance. Van Hove, for all his qualities, is not renowned for either.

Jesus Christ Superstar

Through Feb. 18 at the DeLaMar Theater, in Amsterdam; delamar.nl