Karachi-born conceptual artist Rasheed Araeen’s Islam and Modernism encourages Muslim artists and scholars to learn from the Islamic history of ideas pertaining to modernity in lieu of a Eurocentric discourse. The London-based author juggles philosophy, religion, a short critique of Hegelian aesthetics, and abstract art under one title, taking only the so-called “Arab world” as a reference point of Islamic scholarship and art. As a result, the book is a timely and necessary, but also a puzzling and cluttered read.

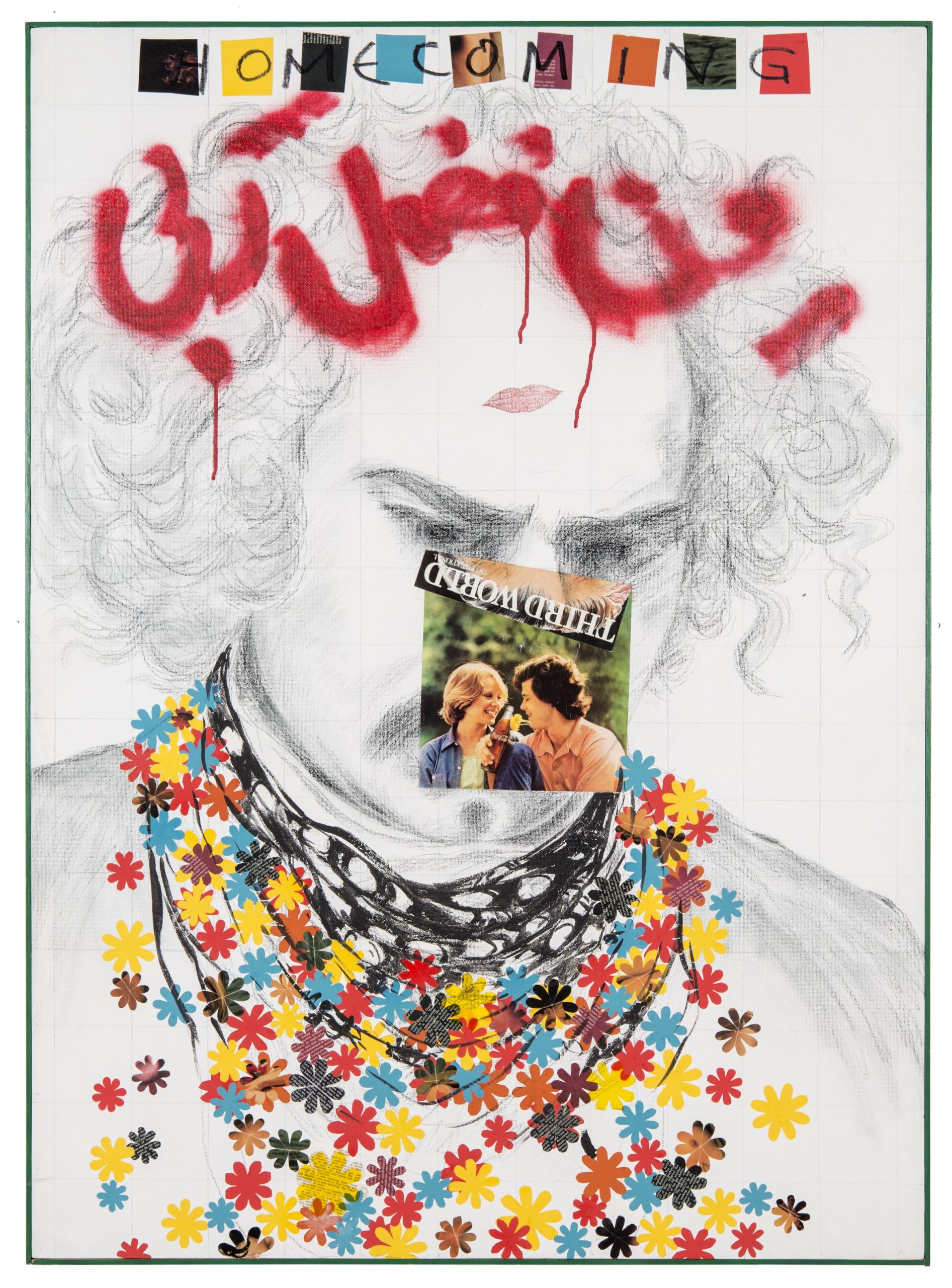

An engineer by education, Araeen is one of the pioneers of minimalism in Britain and co-founder of the art journal Third Text. His geometric sculpture and painting from the 1960s to ’80s brought prominence to the presence of Pakistani diasporic artists largely made invisible by the British art scene. Western art critics of the time could not reconcile his expressions of identity as a Muslim, Pakistani artist interested in minimal, geometric art. He has since been highly critical of Western scholarship that ignores Islam’s spiritual and philosophical ethos, which has influenced modern art created across Islamic cultures.

Araeen concisely turns to formidable Islamic scholarship on modernity, such as works by Indian poet and philosopher Muhammad Iqbal, Swiss writer Titus Burckhardt, and verses from the Qur’an, instead of Eurocentric literature dominated by Christian authors. He writes, “The main issue is Eurocentric modernism and its history, which can be dealt with by redefining modernism and re-writing its history. How can this be achieved when Eurocentric modernism is persistent in its domination of the art world with all its institutions”?

He suggests rectifying this problem in two ways. First, missing gaps in Islamic philosophy and history of knowledge that arise because of deliberate or unconscious ignorance must be addressed by contemporary scholars and practitioners. Secondly, institutions that promote research “liberating” art from Muslim regions from its “subservience to the West” must be established. As an example of the latter, he mentions the Sharjah Biennial in the United Arab Emirates. Araeen cites the case of the influential Pakistani Modern artist Anwar Jalal Shemza, who began to work in Britain in the late ’50s within an art scene that maintained an incompatibility between modernism and the works of non-Western artists influenced by Islamic scripture.

Problems in the text arise when Araeen does not consider the nuances of identity that may not depend on personal religious beliefs. Moreover, in framing West Asia and North Africa as the harbinger of Islam, he does not take other Muslim art traditions into account, especially those of South Asia and West Africa. The complex histories of Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh, which comprise multiple religious identities and historical literatures, are largely absent from the book. Further, to consider only Islamic scholarship in one geographic area is to inevitably isolate Buddhist, Hindu, Jain, and other interlinked intellectual lineages informing one another and co-existing in the same region for millennia.

Islam and Modernism is a readable, provocative polemic deliberating on the present philosophical and aesthetic crises in art from the Islamic world. Though teeming with opportunities for further scholarship, its arguments fail to blossom as an in-depth study. Our first qualm to resolve must be the exclusion of art from “non-Arab” Muslim communities. Assessing the relevance of Eurocentric modernist studies for non-Western art can then follow.

Islam and Modernism by Rasheed Araeen (2022) is published by Grosvenor Gallery and available online.