“In any other time of the past, Joyce’s work would never have reached the printer, but in our blessed 20th Century it is a message, though not yet understood”, said the mystic psychiatrist Carl Jung in the mid 1930s, after a lengthy intellectual engagement with James Joyce’s texts and a professional one with his daughter Lucia, whom he (unsuccessfully) treated for a period of time. The Joycean Society, Dora García’s most recent project, documents the collective efforts of a reading group that, since 1985, has met every week in Zürich to attempt precisely that: understanding the message that James Joyce ciphered in his final novel, Finnegan’s Wake (1939). The premise seems simple and enticing enough; after all, during the last fifteen years García has created a unique constellation of works that have been consistently lucid and stimulating, while Joyce makes for an endlessly compelling subject. But what I couldn’t anticipate was how moving and thought provoking this work would turn out to be.

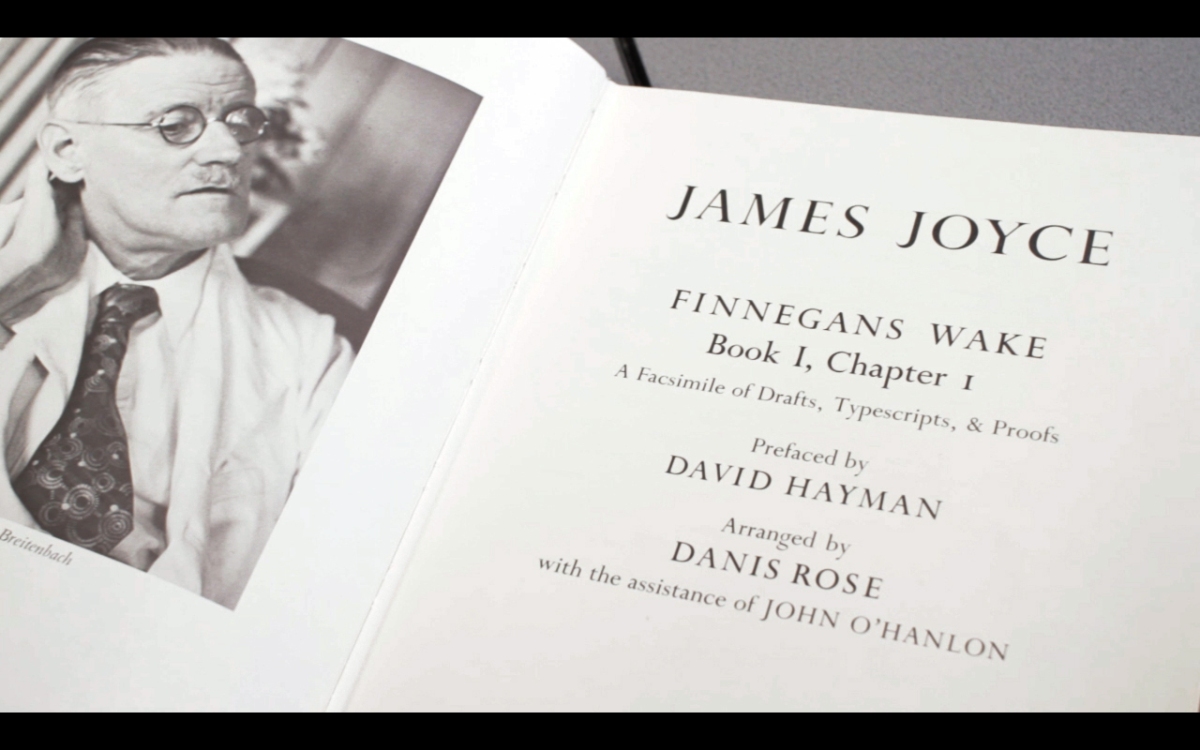

There are several themes in this film that could be discussed. The most immediate one is the pleasures afforded by reading and, more specifically, by reading together: the quest to disentangle a highly complex text as a collective endeavour rather than a solitary one. This is what The Joycean Society is primarily about: producing and sharing knowledge, devoting time to language itself, deconstructing words to their degree zero, savouring each morpheme and phoneme like chocolate dissolving in the mouth. Finnegan’s Wake, of course, provides a rich tapestry for such games: a 600+ page novel whose expressionistic grammar and neologistic multilingual puns have deemed it to be one of the most difficult works of fiction in English literature, as well as one of the most humorous (if you can get the jokes).

If Joyce and Finnegan’s Wake are the subject matter of this work, its protagonists are, without a doubt, the members of the reading group. In the session shown in the film the group is comprised of about ten members, of whom the majority seem to be around 70 years old. These elder members are, logically, the ones that have been part of the group for longer, and they provide a poignant yet good-tempered reflection on the passage of time. “Jesus! I used to be able to run up these stairs when I started… But that was in 1988!” laughs one of the group members, as he arrives breathless and panting to the reading room. At some other point, he says, “I meant recently, and 40 years ago is recent to me…”. This theme is reinforced by the myriad visual details than punctuate the film: we see wrinkles and shaking hands turn the pages of dog-eared copies of Finnegan’s Wake, index fingers scanning its surfaces. Various editions of the novel are produced from satchels, rucksacks and crumpled plastic bags, all of them heavily underlined, with little stickers or scraps of paper marking relevant pages. The binding on some of them has come undone, books now amounting to a stack of loose and yellowed pages only held together by the sustained dedication of their owners. Books as characters, who also endure the passing of time.

The filming style is cleverly adapted to the environment. The camera inserts itself in the group; is part of the group, recording the event almost in real time, from the same height and point of view of the readers. The camera’s movements seem to mimic the act of writing itself, of scribbling in a surface which is space instead of paper, with intuitive cuts and jumps that follow speaking participants and observe the silent ones observing. It shows us details of the room, with posters and memorabilia related to the Irish writer, but also his grave, in Fluntern Cemetery, outside Zürich, where his statue, sculpted in bronze and sporting a cigarette, also whiles away season after season under the sun, the snow and the rain. It is perhaps convenient to point out that, although now considered Ireland’s literary treasure – along with Samuel Beckett–, James Joyce was not always in his nation’s good books. Having fled Dublin in 1904 – when he was only 22 years old – to live a peripatetic existence that took him to Trieste, Paris and Zürich, Joyce’s self-imposed exile was never really forgiven nor forgotten by his fellow countrymen. His remains, thus, stayed in Zürich, where he died in 1941. When his widow Nora requested their repatriation to the Irish government, permission was denied.

But, leaving these meandering thoughts behind and coming back to the reading group, it is interesting to note that we never find out anything specific about these people, with whom we unavoidably bond as the film progresses. We can only deduce that they live in Zürich and, by the various accents that tint their English, that they come from several parts of the world: Switzerland, the UK, the USA… Questions like why do they live in Zürich, what their occupations are or were and why would they be interested in engaging with Joyce’s novel at such a deep and demanding level are never revealed to us. But that, and that is precisely the point, bears no importance at all, since this lack of specificities, this suspension of singularities, doesn’t hinder the relatability of these characters to us and it certainly doesn’t obstruct the mechanics of the group. In that sense, what we witness in The Joycean Society seems a perfect example of what Jean-Luc Nancy developed in his famous essay The Inoperative Community (1986), in which he proposed a new understanding of community built on the principles of shared experience and “being-in-common”, rather than on notions of work or belief, which to him risk totalitarian bias. In his characteristically coiled manner, Nancy argues that “community necessarily takes place in what Blanchot has called ‘unworking’, referring to that which, before or beyond work, withdraws from the work, and which, no longer having to do either with production or with completion, encounters interruption, fragmentation, suspension. Community is made of the interruption of singularities, or of the suspension that singular beings are. Community is not the work of singular beings, nor can it claim them as its works, just as communication is not a work or even an operation of singular beings […].” Crucially, Nancy goes on to elaborate what is it that galvanizes this community by quoting Georges Bataille: “The uncorking of the community takes place around what Bataille for a very long time called the sacred: […] ‘What I earlier called the sacred […] is fundamentally nothing other than the unleashing of passions’”. The idea of passions or, as I prefer, of enthusiasms as a congealing social force is what fundamentally constitutes the “inoperability” advocated by Nancy, which has nothing to do with a flawed or faltering initiative, but with an idea of spontaneity, of sharing, of process. An inclination to come together that has no object or purpose other than itself.

This potential of enthusiasm and open-endedness permeate the whole piece. This is, after all, a group of people who meet weekly to read, painstakingly and sentence by sentence, a novel which is considered almost impossible to understand by many (although there is a consensus to the meaning of some parts of the book, other parts of Finnegan’s Wake remain largely “unsolved”). At their pace, it takes them about 11 years to finish a run of the novel, and the members of the group who first started it in 1985 and have stayed since then, are now in its third consecutive round, their compulsion to crack Joyce’s code undiminished. This is certainly a utopian task, and one that can only be attempted within a group, by means of exchange. They might be aiming at the impossible but, crucially, they seem to derive their pleasure not so much in ascertaining specific meanings, but in trying together, in the process they engage in weekly as a group, whatever the results might be.

Towards the end of the film, Fritz Senn, the director of the Zürich Joyce Foundation and leader of the reading group, ventures an explanation for the appeal of endeavours such as this: “Culture is a kind of substitute for the pleasures that are denied to some of us for many reasons”, he says, smiling sheepishly to someone behind the camera. As the session comes to its end, the group members sit in silence for a few final moments, as the sound of bells tolling in a nearby church drifts through the window. As they pack their belongings quietly, almost lingering, it feels as if they didn’t want to disperse, just as I don’t want to stop watching them, as enveloped as I am by their musings.

–

This essay was first published on input.es in December 2013. You can read the Spanish translation here.