Please bear with me while I jog our recent collective memory a little: on March 11, 2011, at exactly 14.46 local time, a 9.0 magnitude earthquake shook the very depths of the east coast of Japan. Less than an hour after, a massive tsunami started its catastrophic journey across the ocean, claiming lives and devastating entire towns. Towering waves soon overwhelmed the seawall of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, three hundred kilometres north of Tokyo, and disabled its cooling mechanisms, triggering in turn three successive nuclear meltdowns from March 12 to 15. The triple disaster officially killed 18,000 people and displaced over 470,000; 154,000 of which were evacuated due solely to the nuclear accident.

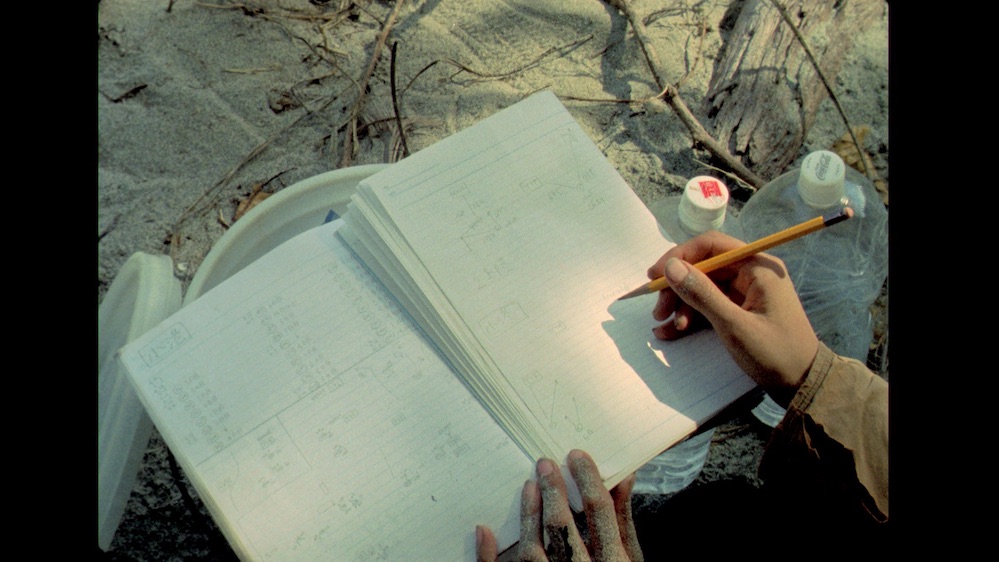

Ana Vaz, still from So long as the sky is recognized as an association (2018).HD and 16mm transfer to HD, color, stereo sound, 15’40’’

We tell ourselves that we know what happened on that exact day, that we have the facts and we have the figures. It’s a control-seeking narrative aimed at countering the unpredictability and strength of nature. But what, then, about the effects, some of them yet to unfold, for human, animal and vegetal life? When do we get to find out about those? Timelines are fuzzy in nuclear spans; the consequences, much like those of climate change, too complicated to envision and thus all too easy to ignore. These, I feel, are some of the questions haunting the Brazilian artist Ana Vaz, who began her spiralling project on the Fukushima disaster back in 2014. This expanding constellation, titled The Voyage Out, gathers 16mm films, HD videos, sound works, text and live performances, all oozing a sense of unstableness and mutability that befits their subject matter. The exact form that The Voyage Out will take in its final incarnation is yet to be seen, although according to Vaz it will assume the guise of a feature film, a medium capacious enough to accommodate its multifarious viewpoints and aspirations. In the meantime, the latest working configuration of this kaleidoscopic endeavour—a teaser of sorts—was recently unveiled at the London-based moving image non-profit LUX, as part of its BL CK B X series.

“You continue to doubt your own madness. Radioactive contamination—which is invisible, which has no smell, no taste—does it really exist? The newspapers, the television, my shrink, my parents: they all tell me that the source of my anxiety, might be non-existent. Is it me whose mind is deranged?” The words of Yoko Hayasuke, a survivor of the disaster who lives in dull fear, become the narrative backbone of the three-channel video installation Mediums (2017), the centrepiece of the exhibition. This perceptive study on trauma and anxiety combines the diaries of Hayasuke, spelt out on flickering red celluloid backgrounds reminiscent of 1960s structural films, with glimpses into a cathartic massage ritual administered in Sendai, a city in the northeast coast of Japan that was flattened by the tsunami. Shot in 16mm, a medium whose texture manages to be both nostalgic and time-less, the images depict a group of middle-aged Japanese women and men shaking under the touch of deft hands. Their bodies twitch, as if erupting in corporeal micro-earthquakes, tectonic movements of the repressed.

Ana Vaz, still from So long as the sky is recognized as an association (2018).HD and 16mm transfer to HD, color, stereo sound, 15’40’’

But not Hayasuke. Where others can only utter formless feelings of dread, she puts words. The young Japanese writer is traumatised by the Fukushima nuclear disaster, and she says so repeatedly. But the world around tells her there’s nothing to be afraid of, that she is overreacting, that the problem is in her mind and not in the air and water that she breathes and drinks, quite possibly polluted with noxious radioactive particles. Could this be a case of institutional, or institutionalised, gaslighting? “It’s not serious, I assure you. You are over-anxious. The lady is not seriously ill, and I am a doctor,” sneers the South American physician to Rachel’s fiancé only a few hours before she dies in Virginia Woolf’s 1915 debut novel, The Voyage Out, which obliquely inspired Vaz’s project.

Today, national and international organisations and government bodies continue to release conflicting reports regarding the extent of the contamination generated by the Fukushima disaster and its effect on humans, earth and oceans. Moreover, because the nuclear incident falls under the State Secrecy Law, which came into force in 2014, independent investigations have been rendered de facto illegal.

Ana Vaz and Nuno da Luz, The Voyage Out Radio Series 2022 ∞ 2222 (2017-18).

Included too in the exhibition were the sound works The Voyage Out Radio Series 2022 ∞ 2222 (2017-18), perhaps the most speculative in the constellation, conjuring up science fiction-like scenarios that explore possible outcomes of the disaster. The three episodes have been produced in collaboration with the Portuguese artist Nuno da Luz, who travelled to Japan with Vaz and crafted an exquisite sound design; an oceanic lattice of field recordings of waves, fireworks, bird calls, bees, drums and rain that transport listeners to shores both real and imagined. The first programme is a faulty transmission from 2222 sent by a time-travelling genderless cyborg stranded on a new island that emerged in the southern archipelago of Ogasawara soon after the major seismic event that started it all. The protagonist begins their transmission with an eerie incantation of radioactive isotopes and their uses in industrial and nuclear products, as well as some of the health hazards they cause. They describe green gradient nights, skies whose former pink and yellow hues have turned a luminous grey because of the radioactive fumes. The voyager tells us that the reason they are reaching out to us via spoken words is to honour the “ancient oral traditions that believed that if we voiced the bad dream we arrested it from happening”. It is a warning message, a whisper from a cybernetic Cassandra that has already seen catastrophe come to a pass.

Yet, in those evoked landscapes, the carcasses of old factories have formed a bed of earth where mutant beans are growing, thriving in fact, while a handful of surviving bees pollinate new radioactive flowers. Meanwhile, mysterious eggs have been laid on the seashore, a host of unexpected creatures buried in the sand. Where did they come from? That’s quite possibly what the group of diggers in the nearby film So long as the sky is recognized as an association (2017) are trying to find out. In it, we only see the back and arms of these researchers, their hands and elbows burrowing in. These are images that go beyond the classic dystopia of death and barrenness. New life forms are conjured up, and the eternal cycle of destruction and renewal enacted once again. In one of the radio programmes, the cyborg describes their inter-temporal voyage from 2022 to 2222 and how, after an period of shock in the face of the expanding nuclear landscape, which was initially seen as “maleficent”, they learnt to accept it, to “live with that trouble”—a subtle rephrasing of Donna Haraway, the spiritual mother of posthuman cyborgs and proponent of learning to live in a damaged Earth.

Ana Vaz, still from So long as the sky is recognized as an association (2018).HD and 16mm transfer to HD, color, stereo sound, 15’40’’

“The Fukushima daisies that sprung […] were freaks of nature, a graceful answer to the disaster, a sign of the immutable fact that live lives on, in all forms,” the cyborg says in their transmission, bringing to mind the film Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959)—another lyrical take on how to rebuild worlds and affects in the aftermath of nuclear disaster whose script was penned by Marguerite Duras. In one of the film’s opening scenes, the female character tells of how the soil in the disaster area is teeming with animals and flowers only a few days after the atomic bombings, even if the images that accompany her assertion are documentary shots of the ravaged faces and bodies of the children caught in them.

This archipelago of conflicting viewpoints and complementary stances is what makes The Voyage Out such a compelling project. Vaz might have skewed a conventional documentary stance, but she’s not shying away from the complicated questions or moral conundrums that should go with it. Her approach is comprehensive without being exhaustive, or exhausting. She prods at the politics of secrecy versus the cathartic powers of disclosure while imagining the concrete effects of the disaster on bodies, territories and minds. She indulges in philosophical speculation, but not before having done fieldwork and collected actual testimonies. Her granular strategy is a convincing methodology, a soup of self-sustaining fragments that coalesce under the frequencies of Da Luz’s evocative sound work, which brings it all together in a dance of light, voices and drones. What’s most refreshing is that despite working with such loaded subject matter, Vaz has allowed The Voyage Out to be loose, hallucinatory, sensual. She beguiles us into staring at nuclear and ecological collapse in the face: bleak, phantasmagoric, looming… and yet, she daringly says, brimming with possibility.

This review was shortlisted for the fifth International Awards for Art Criticism (IAAC) and is reproduced with the consent of the IAAC Ltd.