This Land Is Our Land: Philip Hyde And The American Wilderness At Smith Andersen North Gallery

This Land Is Our Land: Philip Hyde And The American Wilderness

Smith Andersen North Gallery

San Anselmo, Marin County, California

January 25 – March 1, 2014

Opening Reception: January 25, 6 – 9 pm

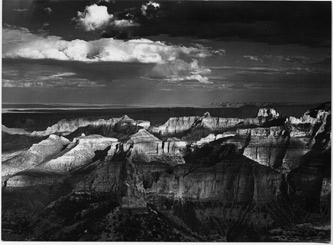

Philip Hyde defended the Western American wilderness with a camera for nearly 60 years, working with the National Audubon Society, Wilderness Society, Sierra Club, and other environmental organizations. He studied at the California School of Fine Arts, now the San Francisco Art Institute, in Ansel Adams’ ground breaking photography program with Minor White as lead instructor and Edward Weston as field mentor. Imogen Cunningham, Dorothea Lange, Lisette Model and other notable West Coast photographers were guest lecturers. This training gave Philip Hyde a solid creative foundation for evolving into one of America’s most respected landscape photographers.

Philip Hyde’s photographs helped protect the Grand Canyon, Point Reyes National Seashore, Redwood National Park, North Cascades National Park, Canyonlands, Big Sur, the Wind River Range, Sequoia National Park and many other national treasures included in more wilderness campaigns than protected by any other photographer of his time. It all began when David Brower and Richard Leonard of the Sierra Club sent Philip Hyde on the first assignment ever for an environmental cause to Dinosaur National Monument where the canyons of the Yampa and Green Rivers were threatened by two proposed dams.

David Brower called Philip Hyde his “go-to photographer,” because when the Sierra Club needed to look closer or show the public an area’s natural beauty, Philip Hyde, young, eager and hungry, dropped everything and traveled across the West capturing sensitive lands on film, thereby becoming one of the primary illustrators of the Sierra Club Exhibit Format Series. The Sierra Club Books Series, originally conceived by Ansel Adams, Nancy Newhall and David Brower, became the public face of the fledgling modern environmental movement during the 1950s and 1960s.

Color photography became an important feature of the Sierra Club Books when color reproduction quality improved enough that David Brower and the Sierra Club publications committee encouraged Philip Hyde and Eliot Porter to envision their book projects in color to more powerfully amplify environmental campaigns. Philip Hyde and Eliot Porter were responsible for establishing color landscape photography as an art in its own right. Philip Hyde’s compositions inspired a generation of photographers, both directly and indirectly, and his techniques are still emulated in current landscape photography today.

Philip Hyde’s images have appeared in more than 80 books and over 100 other publications, including Aperture, the New York Times, Life, National Geographic, Fortune, and Newsweek. Not only did Philip Hyde receive many awards and honors throughout his career, his photographs were shown in major museums and galleries nationwide, including the Smithsonian Institution and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

David Leland Hyde, Philip Hyde’s son, will speak at the Smith Andersen North opening reception on January 25. David Leland Hyde is an accomplished photographer in his own right, a photo historian and ambassador of his father’s photography to the world’s best galleries, museums and collectors.

For more details see the blog post, “Major Northern California Philip Hyde Exhibition.”

This Land Is Our Land: Philip Hyde And The Wilderness West

January 25 – March 1, 2014

Opening Reception January 25, 6 – 9 pm

Presentation At 7 pm

Smith Andersen North Gallery

20 Greenfield Avenue

San Anselmo CA 94960

415 455 9733

SOURCE: Fine Art Photography Collector's Resource - Read entire story here.

Read More