Late in a groundbreaking career, Jacob Lawrence looked up from his work and had a revelation. The tools of his trade were everywhere around him, and suddenly they meant something more.

They were tools that he shared with others, the very people he painted—African Americans creating a place for themselves in America. These people created a community as well, a community of builders. In more than one sense, they were breaking ground themselves. Soon, too, they became the subject of Builders, at D. C. Moore in 1998 and at that very gallery this fall, through September 28 (and so sorry I could not post this in time for you to catch someone this important).

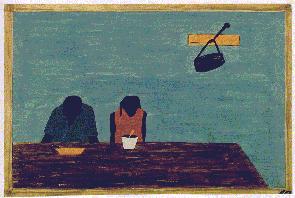

Of course, that sudden revelation never took place. Lawrence identified all along with his subjects and saw them as builders. It took decades for black Americans to claim their rightful place, a task that is still far from complete. He first described the community as itself a work in progress. You can see it in the titles of his most famous paintings, The Migration Series and Struggle. He was also a perfectly self-aware and reflective artist, happy enough to paint a compass and right-angle straightedge, with all the rigor they brought to drawing. He could see perfectly well that the same plane in a carpenter’s toolkit served him to make a stretcher and to make its edges clean.

When it comes down to it, Builders was only a coda to thirty years of relative decline. He painted the Great Migration from the rural south in tempera on sixty small panels in 1941, when he was just twenty-three, and his history of the American people as a struggle in 1954. His paintings of builders came just two years before his death in 2000. Perhaps he felt it as a renewal. He could go back to the flat bright colors and fields of black that he had introduced in tempera, but now he could apply drawing and color to a building. He could in turn apply those same patterns and colors to human flesh.

If Lawrence identified with his work and with a builder, he identified the builder’s work with the worker. Unfortunately, the gallery exhibits just one of twelve paintings together with work on paper, but it makes the point well. Buildings tilt at improbable angles, flattening the entire painted surface, while conveying mass and depth. They claims his work for both Modernism and realism. They give new meaning to formalism, too, with a carpenter’s insistence on form. And then the same brickwork covers the people, painterly brick by brick.

Still, I like to imagine a moment of discovery. I first saw The Migration Series in 1995, when it came as a revelation to me. (It led to one of the first reviews on this Web site.) The Met back then exhibited the series and Wassily Kandinsky in adjacent galleries, demanding a choice on the way in. Art history, it seemed to say, had made its choice, excluding a black man’s seeming crudeness in favor of Europe’s relentless experiment, and it was time to look at history anew. Besides, Kandinsky’s wild horses are a kind of folk art in themselves.

Still, I like to imagine a moment of discovery. I first saw The Migration Series in 1995, when it came as a revelation to me. (It led to one of the first reviews on this Web site.) The Met back then exhibited the series and Wassily Kandinsky in adjacent galleries, demanding a choice on the way in. Art history, it seemed to say, had made its choice, excluding a black man’s seeming crudeness in favor of Europe’s relentless experiment, and it was time to look at history anew. Besides, Kandinsky’s wild horses are a kind of folk art in themselves.

These days The Migration Series is on display in its entirety nearly all the time, in MoMA’s collection. Lawrence, though, is still looking back. He respected old-fashioned studio training, and he could use it to recall an African American’s roots. The gallery displays some of his weathered tools along with works in charcoal, pencil, and gouache, and their wood would never make it into a hardware store today. And yet the same care that goes into a builder’s anatomy powers wild, fragmentary shapes and colors. Storytelling approaches abstraction. And the white of a black man’s eyes matches the ghostly silhouettes of his tools.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.