Official notice: you can become an outsider artist without ever venturing outside. Plenty of artists have, but not Anthony Dominguez on the cold streets of New York. Only now is he receiving a less chilly reception not so very far from where he once lived, at Andrew Edlin through April 6.

Outsider artists have often been insiders in everything but their art. Many have worked diligently within a community, like the Gee’s Bend quilters, and folk art in portraits has become an emblem of early American art. Yet a step outside the art world was never enough for Dominguez. He took to the streets for over twenty years until his death in 2014, and his art does nothing to disguise the costs. For him, even a cat begs to cat-sit for pay. Baby, it’s cold outside.

Some outsider artists have been trapped inside with their madness, in an institution or in their head. And there is no getting away from the madness of his decision. Others artists have grown up in an artistic family, in his case with a commercial artist for a father, or dropped out after a few courses in art and headed for New York. Not everyone, though, abandoned an East Village apartment at the very depth of East Village malaise and the very peak of East Village art. Dominguez had to be ingenious just to survive, making art from whatever scraps he could find. Not surprisingly, he never made it to his mid-fifties.

Not that he cared all that much about the label outsider art, and he had one dealer and then another. Without them, his work could not have survived, although both galleries passed away as quickly as he. Yet he valued nothing so much as freedom, and nothing less than homelessness would do. One can see it in the show’s very first work, where Lady Liberty in jail comforts a fellow prisoner. “What are you in for?” “Breathing.”

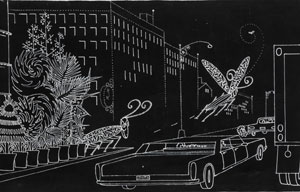

It is the closest Dominguez comes to hectoring. Uncle Sam and a cop with a dollar sign for a head parade right by, while others behind bars are either catching what sleep they can or dropping like flies. Once back on the street, though, his bitterness melts away. A comfortable jogger is just part of the pageantry, along with a man rich enough to toss a bill into one trash can, waste paper into another. In time, he found religion, but giant insects appear more often than a savior. Text within paintings accepts everything he saw, like one that gives the show its title, “Kindness Cruelty Continuum.”

The gallery pairs it with a second show for writing found on the subways, in fake ads, doctored posters, and handwritten rants. Are they witty, tedious, or hateful? All of the above, and Kenneth Goldsmith, who collected them along with Harley Spiller, gives them a name from his poetry, “Are You Free on Saturday from 4–7 PM?” The words look suspiciously like an invitation to his opening, with tabs at bottom for your RSVP. Like Dominguez, Goldsmith would welcome anyone who can make it before 7. I just hate to think whether they would shut up.

The gallery pairs it with a second show for writing found on the subways, in fake ads, doctored posters, and handwritten rants. Are they witty, tedious, or hateful? All of the above, and Kenneth Goldsmith, who collected them along with Harley Spiller, gives them a name from his poetry, “Are You Free on Saturday from 4–7 PM?” The words look suspiciously like an invitation to his opening, with tabs at bottom for your RSVP. Like Dominguez, Goldsmith would welcome anyone who can make it before 7. I just hate to think whether they would shut up.

Those scraps of raw prose underscore the sophistication of white on black for Dominguez. He brings totemic patterns to large works, in his paint’s chalk-like line on black, and a delicate texture to decals pricked with bleach. He also brings color and the look of traditional samplers to songs after teaching himself to write music. Even the street scenes stop short of cartoons, although one might as well call them a graphic novel. Yet he would still rather be alone. As one lyric begins, “Company loves misery.”

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.