Where would environmentalism be without architecture? Nowhere, of course, when so much depends on building for a sustainable future.

Nowhere, when planners can build away from endangered species, burning lands, and rising seas. Nowhere, when they can capitalize on urban density to fight suburban sprawl. Nowhere, when everyone deserves easy access to mass transit, parks, wilderness, and gardens, for greener cities in a greener nation. Nowhere, too, when buildings themselves can reduce their carbon imprint and their shadow. It could have the added payoff of more affordable housing without cookie-cutter houses. They could become responsive to nature, responsible to nature, and self-regulating.

Well, surprise, for environmentalism is not just a vision of the future: it is a vision of the past. The Museum of Modern Art finds “Emerging Ecologies” going back at least seventy years—and peaking long ago. Yet it stakes that claim on ignoring almost every one of those needs for the future. But then it is really asking a different question altogether, through January 20. When it sees architecture as essential to environmentalism, it means to the birth of environmentalism and its very existence, not its potential.

The curator, Carson Chan, takes the long view. A time line starts with the Tennessee Valley Authority, the New Deal program that provided electricity, flood control, and economic recovery—and, as its next date, the dropping of the atom bomb. If that already sends mixed messages, “Emerging Ecologies” ends soon after 1970 and the first Earth Day. It has no room for stronger federal regulation, greener lifestyles, cleaner skies, and a growing recognition of climate change today. It has no room, too, for the grayer architecture that long ruled. It has no time because it looks back to an alternative that barely existed.

Did environmentalism really peak long ago, and did architecture inspire it rather than the other way around? A show subtitled “Architecture and the Rise of Environmentalism” opens with Buckminster Fuller and Frank Lloyd Wright, although almost all their urban visions never came to be. It can hardly help doing so, because the public cannot get enough of Wright’s Guggenheim Museum and Fuller’s utopias. It can hardly help it either because they were on to something, and others knew it. Aladar and Victor Olgyay, who used vents to ensure a “comfort zone” of temperature and humidity, worked in 1956, just ten years after Fuller’s Dymaxion Dwelling Machine. Eleanor Raymond and Mária Telkes designed a glass Sun House, a fitting sequel to Wright’s 1937 Fallingwater.

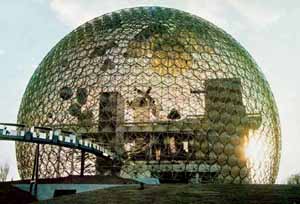

Still, that is slow progress, and it should set off alarms. Wright had designed a unique luxury home in western Pennsylvania that few will ever see. Fuller’s proposed machine depends on a mechanical nightmare within a harsh aluminum dome. Soon enough, his more inspiring geodesic dome became the U.S. Pavilion to an international exposition, Murphy & Mackey were adapting it to a Climatron in Saint Louis, and Eames Office with Kevin Roche and John Dinkaloo were constructing a National Fisheries Center in the nation’s capital. They, too, though, can seem more a self-indulgence than a model for today. When the Cambridge Seven imagine a rain-forest pavilion like a tropical snow globe, they are not preserving nature but enclosing it.

When Fuller himself proposes a glass dome over Manhattan, it looks merely silly. When a group called Ant Farm hopes to open a “dialogue” with dolphins, it may sound like fun. When Michael Reynolds conceives of a six-pack as the “basic building block” of a beer-can house, it is simply chilling. It is nothing less than marvelous when Carolyn Dry designs a port city close to dolphins, based on coral’s natural growth. It is nothing less than essential when Wolf Hilbertz outlines the restoration of a coral reef. Still, sometimes humans should know when to leave nature well enough alone.

Environmentalism thrives on data, and architects can help collect it. Ian McHarg and his students make a long-term study of the Delaware Upper Estuary, and Willis Associates has its Computerized Approach to Residential Land Analysis (or CARLA), while Fuller’s World Game is no more or less than a world map. Still, that map takes up as much space as a football field. Environmentalism also thrives on science, and NASA or Princeton’s G. K. O’Neill has every reason to think about space colonies. Discovering the laws of physics will take long observation up close.  Still, can taking the human footprint into space seriously reduce it on earth?

Still, can taking the human footprint into space seriously reduce it on earth?

The problem is not an excess of idealism. It is what counts as environmentalism. The story really does end too soon. Other shows have called for “Space Between Buildings” and garden cities, but not this show. If anything, it calls for suburban sprawl. James Wine does with his Forest Building, and so does Malcolm Wells in going underground, even if he covers his suburb with soil. Protests have their place, like those of Anna Halprin, a choreographer, but they are not green architecture.

Maybe the problem lies in taking them too seriously. These are indeed idealists, and their environmentalism has less to do with design for a healthy future than with inspiring. Eugene Tssui creates images worth remembering with his wind-generated dwelling. So do Ralph Knowles with his “solar envelope” and Glen Small with his “green machine,” of trees on a tiered roof. I have never seen a model of Fallingwater as large as the one at MoMA. More than anything that came after, it takes my breath away.