Why did J. P. Morgan assemble the Morgan Library? It was not just because he liked to read—although the three-tiered shelves and walkways of his private library, still a highlight of the larger public institution today, could make anyone a reader without so much as opening a book.

He collected to show his humble deference to scholarship and art. He could show his piety as well in just what he collects. At the same time, he was boasting of his wealth—a wealth of knowledge, power, and cash. How appropriate that two shows now focus on Morgan’s Bibles and “Medieval Money.” They and a smaller show of “Early Modern Herbals,” or age-old guides to the healing properties of plants, also single out a century or two when all these things came to be. “Morgan’s Bibles” takes special pride in them all, with an emphasis on Morgan himself, through January 21.

Of course, the same questions arise with collectors today—all the more so when museums (yet again) exhibit a private collection. (Yes, that means a gift coming up.) How are collectors, even one as savvy and sensitive as Spike Lee, distorting the role of museums and the art scene? That includes the Morgan’s own turn to recent art. How refreshing, then, to return to a time when J. Morgan was just getting started and could not stop. “Morgan’s Bibles” sticks largely to what he himself collected and its role in the collection.

Not exclusively, mind you, and the Morgan (which has previously displayed The Crusader Bible) does not make it obvious when his choices end and others begin, but close enough. It also has an expansive view of the Bible. It includes psalters, of course—not just the Psalms and prayers taken from the Bible, but also a setting to music on behalf of John Calvin. Who knew that the stern Protestant preaching original sin wanted you to sing? It has drawings and prints merely because their scenes draw on the Bible, but then how much older art does not? A fine porcelain of the Holy Family comes close to the viewer in proximity and scale—enough to put anyone in the place of the shepherds or the wise men.

Artists as different as William Blake and Filippino Lippi depict Job close to despair. His “comforters” gesticulate cruelly for Blake, dutifully for Lippi. A drawing by Anthony van Dyck displays his command of anatomy and vitality, even as Jesus is as grisly as death. The show has among the largest of Rembrandt prints. He bathes the crucifixion in a shower of light, even as the thieves on the cross and the mob on the ground sink in darkness. He shows the mocking of Jesus as a multi-tiered display of statues, spectators, heroism, and terrible abasement. Rembrandt’s scratchy, compulsive line has never been more evident.

Still, an expansive show makes sense given the roles of the Bible in real life. Morgan had more than one role as well. Even while he nurtured his library, he served as president of the Metropolitan Museum, doing far more for its growth than many a curator today, much less than the work of presidents overburdened with fund-raising today. He also considered himself a devout Episcopalian, which did not in the least stand in the way of showing off his love of wealth. Some books are leather, enhanced with clasps, crystals, and other finery, some embroidered. Here you can tell a book by its cover.

His scholarship appears from the start, with a Bible that divides its pages into blocks for Hebrew and other languages. Scholarship appears, too, in German and English editions. The Morgan has famous translations by William Tyndale and Myles Coverdale in the 1500s, the Great Bible commissioned by Thomas Cromwell for Henry VIII, and a King James Bible first edition. They testify to two more roles for the Bible as well, reaching our and reaching kings. Embroidery was largely limited to a guild with privileged status, but not entirely. Anyone with a needle and thread could, at least in principle, give it a go.

His scholarship appears from the start, with a Bible that divides its pages into blocks for Hebrew and other languages. Scholarship appears, too, in German and English editions. The Morgan has famous translations by William Tyndale and Myles Coverdale in the 1500s, the Great Bible commissioned by Thomas Cromwell for Henry VIII, and a King James Bible first edition. They testify to two more roles for the Bible as well, reaching our and reaching kings. Embroidery was largely limited to a guild with privileged status, but not entirely. Anyone with a needle and thread could, at least in principle, give it a go.

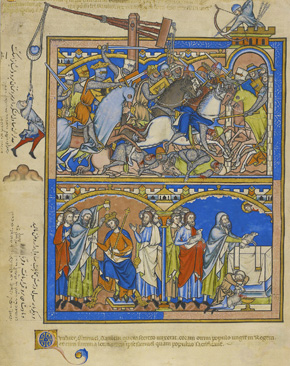

Like other illuminated manuscripts, these also testify to a role in art history. The delicate realism of a Bible from Tuscany dates to the 1490s, before a Renaissance in sculpture and painting. As late as Peter Paul Rubens, artists were still copying miniatures as well. Always, though, Morgan was out there collecting. Photo shows him in Egypt’s desert sands and taking lunch in a Persian temple. Whether the message of the Bible reached him I leave to you.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.