Among the most common entry points to cartophilia are representations of where the collectors have set foot in real life. For New Yorkers willing to spend, say, about $280,000 on a 1770s map of the city, they can study how “Brookland Parish” has lost all traces of its pastoral roots yet maintained Colonial-era place names like Red Hook and Flatbush.

“There’s so much that’s recognizable, yet there’s so much that’s different, it just sucks you in,” said Matthew Edney, a professor of geography specializing in the history of cartography at the University of Southern Maine, affiliated with the university’s Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education. He added that at times, “the past is a foreign country.”

J. C. McElveen, a retired lawyer in Maryland who owns about 1,400 maps dating back to the 16th century, said that one of his treasures is only a few years old. His wife, Mary, made him a personalized map out of modern maps, showing where they have lived and traveled for decades. “You look at those,” he said, “and memories are triggered.”

Tania Rossetto, a professor of cultural geography at the University of Padua, keeps a contemporary map of Italy on her children’s bedroom wall. It serves, she said, as “a meeting place where our fingers trace memories and dreams of family trips made, and to be made.”

Dennis M. Gurtz, a financial planner in suburban Maryland who owns about 1,000 maps dating to the 1590s, warns that collections can start deceptively small. But then, after perhaps three purchases, the “old map pox” kicks in, and the shopping sprees begin. “Be very careful,” he said. Severe cartophilia is diagnosable when wall space runs out and the buyers start squirreling away maps in storage. That moment is “a vital inflection point,” said Michael Buehler, the founder of Boston Rare Maps.

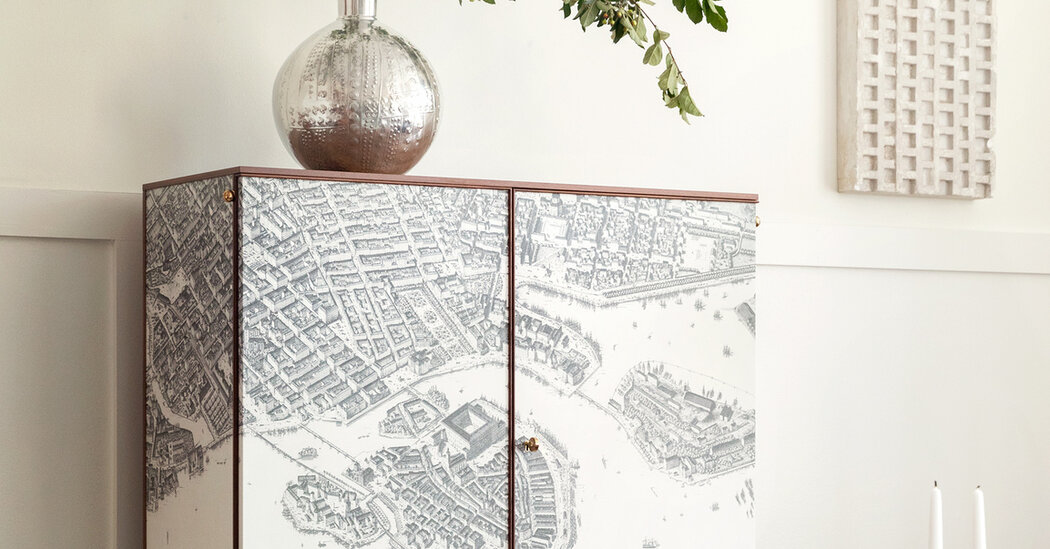

Svenskt Tenn’s new cabinet, sheathed in the 1870s map of Stockholm, pays homage to the wanderlust of the company’s leaders. Ms. Ericson and her husband, Sigfrid, a sea captain, globe trotted for design inspiration while bringing home souvenirs, including antique maps. Mr. Frank and his Finnish-born wife, Anna, settled in Sweden after escaping from Nazi persecution in Vienna and also spent years in New York. Mr. Ahlden, Svenskt Tenn’s curator, said that Ms. Ericson liked to paraphrase a quote from Saint Augustine: “The world is a book, and those who stay home are reading only one page.”