Kristin here:

Once again the fall semester approaches, and educators are pondering their film-class syllabi. As always, we have prepared a guide to our blog entries from the past year, with suggestions about how some of them might usefully be assigned alongside chapters of Film Art: An Introduction. Readers who aren’t teaching could use this guide to alert them to entries they may have missed.

For the entries from past years, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013.

David is at work on a book on 1940s Hollywood cinema, which he finds a strange and innovative era. Several of his entries for this past year reflect that focus.

Chapter by chapter

Chapter 1: Film as Art: Creativity, Technology, and Business

Last year several of our entries dealt with the conversion of exhibition from film to digital copies. That conversion has progressed until 35mm houses are now relatively rare. We take a look at a theater still showing movies on film in “Dispatch from another 35mm outpost. With cats.”

Chapter 3: Narrative Form

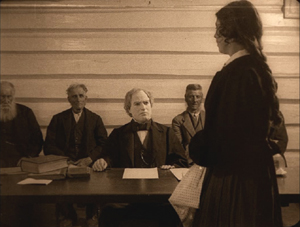

Sometimes producers force scriptwriters to change their scripts. These changes aren’t always bad. They can lead filmmakers to find ingenious solutions that actually enhance the result. We look at some examples from the 1940s in “Innovation by accident.” (As in Kitty Foyle, above.)

Two professors have already told me they were going to teach Gravity this coming semester, assigning our two entries on the film. These could be used for a variety of chapters: the first one, “GRAVITY, Part 1: Two characters adrift in an experimental film” is on the narrative of the film and could most obviously assist in teaching Chapter 3. It might also be a helpful reference, however, for Chapter 10, in discussing the boundaries between experimental and mainstream cinema.

The differences between suspense and surprise is a common topic in discussing narratives. We look at Hitchcock’s famous distinction between them and where he got it in “Hitchcock, Lessing, and the bomb under the table” and “Hitchcock Again: 3.9 Steps to Suspense.”

For advanced students, you might consider assigning an essay David has posted on his website proper, “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative.” He elaborates on this essay with examples from Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street in “Understanding film narrative: The trailer.”

Modernism involves playing with plots, sometimes in challenging ways. In another entry for advanced students, we examine such playfulness: “Pulverizing plots: Into the woods with Sondheim, Shklovsky, and David O. Russell.”

During the 1940s, filmmakers sometimes explicitly broke their films down into chapters. That tradition has not disappeared–especially in the films of Quentin Tarantino. We explore some connections in “The 1940s are over, and Tarantino’s still playing with blocks.”

Chapter 4: The Shot: Mise-en-scene

Staging is an important aspect of acting. We give some historical notes about how characters have been set up to face each other in a two-shot composition in “Where did the two-shot go? Here.”

Few directors combine staging, setting, composition and actings as brilliantly as Kenji Mizoguchi. We explore his extraordinary mise-en-scene in “Mizoguchi: Secrets of the exquisite image.” (Above)

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

In anticipation of Gravity‘s release, we wrote about long takes in Alfonso Cuarón’s earlier films and in particular Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban in “Harry Potter treated with gravity.”

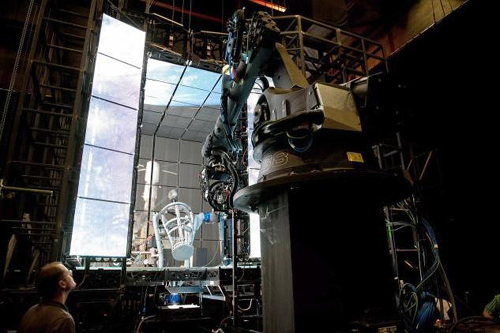

Our second entry on Gravity, “GRAVITY, Part 2: Thinking inside the Box,” could be taught in connection with the entry on Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban in discussing long takes. It also, however, exemplifies cutting-edge techniques in digital cinematography, special effects, and 3D.

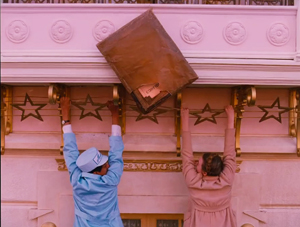

Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel wonderfully exemplifies variations on aspect ratios. Its style is also based on framing perpendicularly to the backs of sets (earlier explored in “Shot-consciousness”). See “THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL: West Anderson takes the 4:3 challenge.” (Above)

Chapter 6: The Relation of Shot to Shot: “Editing”

At the Vancouver International Film Festival, we caught Walter Murch’s lecture on the industry’s transition to digital editing. Here’s our write-up: “Film-industry pros share secrets in Vancouver.”

Our two Wes Anderson blogs (here and here) discuss his customized variant of classical continuity editing.

Chapter 8: Summary: Style as a Formal System

Nebraska

Teaching about auteurism and style? Kristin met Alexander Payne last year at Il Cinema Ritrovato. Then he came and visited Madison this past spring. We blogged about that visit and his films in “Alexander Payne’s vividly shot reality.” He was still talking to us at Il Cinema Ritrovato this year, so he must have liked the entry!

Chapter 10: Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

We wrote an entry on a major recent documentary film, “I am a camera, sometimes: Tim’s Vermeer.” Also quite teachable.

Chapter 11: Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

If you show Tokyo Story, or any other Ozu film, your students might be interested in Ozu’s influence up to the present day. Our entry “Look well! Look again! Look! (For Ozu)” explores this subject.

Apart from the entry on The Grand Budapest Hotel linked above, we’ve written an analysis of his previous film in “Moonrise Kingdom: Wes in Wonderland.” His recent films, starting with Fantastic Mr. Fox, strike us as very teachable.

David has written several entries on some major American critics of the 1930s and 1940s–Otis Ferguson, James Agee, Parker Tyler, and Manny Farber–and their approaches to analysis and evaluation. These would be suitable for students interested in writing film criticism themselves.

“Otis Ferguson and the Way of the Camera”

“The Rhapsodes: Agee, Farber, Tyler, and Us”

“Agee & Co.: A Newer Criticism”

“James Agee: All there and primed to go off”

“Manner Farber 1: Color commentary”

“Parker Tyler: A suave and wary guest”

and finally “The Rhapsodes: Afterlives”

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Traditions and Trends

If you are looking for silent films to show as illustrations of German Expressionism, French Impressionism, silent classical Hollywood, or very early experimental cinema, try the latest entry in our surprisingly popular annual summary, “The ten best films of …1923.” Not all the films are available on DVD at this point, but the ones that are are well worth seeking out.

Examples of early film and the transition to more classical storytelling can be found in our summer entry, “What’s Left to Discover Today? Plenty.”

An update to the Hong Kong section of the chapter can be found in our entry on Wong Kar-wai’s latest film: “THE GRANDMASTER: Moving forward, turning back.”

Further resources

For information on some recent DVD and Blu-ray releases, see “Recovered, discovered, and restored DVDs, Blu-rays, and a book.”

We’ve put up an ebook on Christopher Nolan, based on updated versions of our blog entries, for $1.99. It includes some brief extracts from Nolan films, though you can opt for a version without the clips. For a description, see “Our new e-book on Christopher Nolan!

Don’t forget that we also have videos available for you to show or assign. For Chapter 3, on narrative, there’s “Twice Told Tales: Mildred Pierce,” including an imbedded Vimeo comparison of scenes repeating a crucial action. Chapter 6′s discussion of editing is supplemented by our most popular video, “Constructive Editing: Robert Bresson’s Pickpocket (1959).”

For the history chapter (Chapter 12), there are two video lectures: an entry on “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies 1908-1920″ and one on “CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See Without Glasses” (which could also be used in connection with the Cinematography chapter).

Gravity, production photograph

SOURCE: Observations on film art – Read entire story here.