Ibrahim Mahama is best known for exploring the politics of labour through monumental installations and wall-based works. His art has made extensive use of old jute sacks (the kind used to carry cocoa or coal), but for his latest public commission, Mahama has collaborated with hundreds of craftspeople to weave and sew 2,000 square metres of fresh cloth embroidered with more than 130 second-hand batakaris (Ghanaian tunics traditionally worn by men). The result: a vivid purple-pink covering that swaddles the brutalist concrete facade of the Lakeside Terrace at the Barbican Centre in London. Weighing 20 tonnes and installed using a complex system of levers, Purple Hibiscus (2023–24) is at the Barbican from 10 April–18 August as part of the exhibition ‘Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art’, which is on show until 26 May.

Ibrahim Mahama. Photo: © Christian Cassiel and Barbican Centre

Where is your studio?

It’s in Tamale in northern Ghana, where I was born. When I was living in Accra during my MFA, I had various ‘studios’ – I was working in market spaces, on the railway or under bridges – because I like the idea of producing art in the public domain. I’m interested in the idea of decommodifying the arts.

When I finished art school, I decided to go back to Tamale to build a studio. I thought I could somehow use it to influence a new generation of artists and thinkers. In 2014 I bought some land on which to build my studio, Red Clay, in a farming community outside the city.

For me, a studio isn’t just a place where an artist produces objects. Red Clay also holds the Savannah Centre for Contemporary Art (SCCA). It has a 900-square-metre hall used for retrospectives, we exhibit archives and other materials in another hall, and the main studio is used for showing parts of the permanent collection.

The Savannah Centre for Contemporary Art (SCCA) in Tamale, Ghana, at its opening in March 2019. Photo courtesy White Cube

There’s also Parliament of Ghosts (2019), a work I made in Manchester (at the Whitworth) that I rebuilt here as an extension of the studio. We use it for talks and all kinds of public programmes and experiments.

We also have a library, a 15-room residency space for artists and writers, which I’ve been building for a while now, and two cinema halls, which I’m now using as studios to produce tattoo-based works on leather for a show at the Fruitmarket in Edinburgh. Then there’s a 2,000-square-metre space that’s supposed to be for archaeological exhibitions but currently shows large commissions I’ve made for museums.

This year we’re beginning work on a new building: a 10-storey-high art school with studio spaces. We also have farms, our own mosque, our own police station. You get an idea of the vastness of SCCA – it’s like a town. The aim is to build an environment that is centred purely around creativity.

For me, the idea of the studio in the 21st century goes back to a pedagogical question about the distribution of art. Even if I’m just sketching in the studio, I’ll invite school kids who will watch me draw before we do a drawing session together. I have to use residual capital from the art world to build alternative systems, but it’s important to me that the work addresses local concerns before being distributed globally.

Installation view of Transfer(s) (2023) by Ibrahim Mahama at the Kunsthalle Osnabrück. Photo: © Friso Gentsch/Lucie Marsmann/Angela von Brill; © the artist

How would you describe its atmosphere?

It’s very friendly and open-minded. Every day when I wake up there are maybe five buses with 400 school kids who are already there. And then I go down, open the studios up and show them work that I’ve done or exhibitions by other artists.

I started out with this idea of transforming art from a commodity into a gift. Everyone here, even the security men and caretakers, is invested in the work. There are older kids in the community who come around the exhibitions so much that they can now give other kids tours.

What are the challenges of working in this way?

Sometimes I think I’m still trying to understand what I’m doing. There’s also the problem of co-ordination: sometimes when I’m travelling I’ll get a request for something, and I’ll say yes, but then maybe the memo doesn’t get across to the studio. When you’re working with large communities, there are always conflicts that are bound to happen. Also, capital: there’s a lot going on and it puts pressure on me to find creative ways of working to earn money to sustain it.

All this work is a proposal I’m making: to inspire other artists to think differently about what their practices could be. It’s certainly not for me and it’s not even for our generation, but for a generation ahead.

Installation view of A Friend (2019) by Ibrahim Mahama at Caselli Daziari di Porta Venezia, Milan. Photo: Marco De Scalzi; courtesy Fondazione Nicola Trussardi; © the artist

How did you create your Barbican commission, Purple Hibiscus?

It started off as a joke. When I was asked to do it, I said, ‘Oh, normally I make work that has very dull, subdued colours. Wouldn’t it be interesting to make something very bright and pink to counter the grey English weather?’ I sketched an idea, then worked with my uncle to help find and coordinate with weavers across Tamale. They wove about 2,000 square metres of fabric in three months. Everything that you see in the Barbican was done by hand.

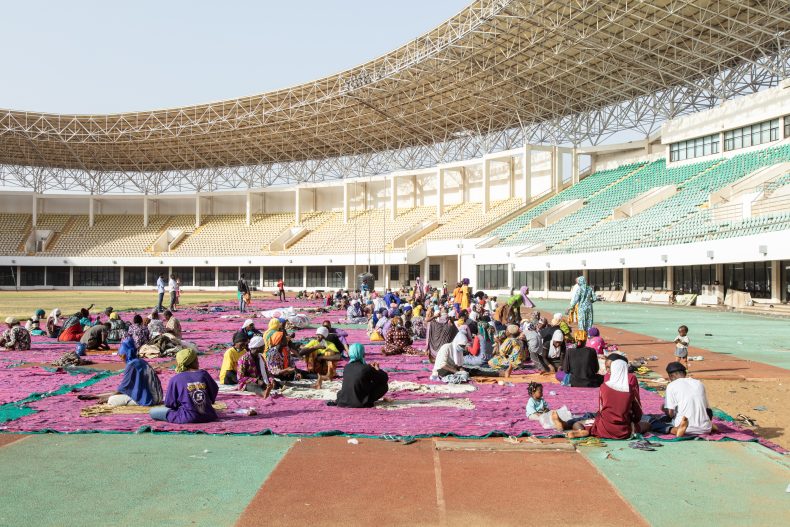

Given the scale of the work, I thought the local sports stadium would make a good studio – I was interested in the architecture as seen against the production of the work. It was difficult, though, because there are always football matches on. We also had to move with the sun, as the shadow of the superstructure shifted across the day.

I’m currently editing a film that shows the work being made from scratch, including the fabric being woven and drone footage of the sewing. For me, the labour factor of this work is very important. The installation is the residue of the performative work of stitching and so on.

Purple Hibiscus (2023–24) being sewn at Aliu Mahama sports stadium in Tamale, Ghana. Courtesy the artist/Red Clay, Tamale/Barbican Centre, London/White Cube

Do you ever play music – or listen to anything – while you work?

The studio is still under construction, so sometimes there’s the noise of earth-moving equipment, say. You also hear bird sounds and the bats that live in people’s roofs – they’ve moved into the gaps in our walls. In the evening, they fly out in a big swarm. I do play music once in a while, but mostly I just like to have peace and quiet in order to think.

What’s the most unusual object in your studio?

I would have said the trains and aeroplanes, but they don’t really surprise me anymore. I’ve bought trains that were built in the colonial era – the British built a railway in Ghana between 1893 and the 1920s. A lot of the labour came from the north of the country, but when it was finished, none of the wealth came there. A lot of these train lines have been scrapped – they cut the trains into pieces and sell them or melt them down. I built a railway line at the studio and put the trains there; we do performances where we pull them. We also use them as classroom spaces. I’m interested in the layers of history within these objects, which are some of the most fascinating (and also the biggest) things I’ve collected. When I leave them outside, they age like fine wine.

Lots of the materials I collect (for my work) were originally used for the transportation of commodities and have since been discarded. I focus on their history, on the void that’s within them. I use the void as a way of giving birth to new life.

I’ve also been collecting the interiors of old factories built in the post-independence era; some were never used and were just abandoned. I buy interiors of those I know are going to be destroyed, and work with a team of welders and so on to remove the objects. The idea is to rebuild the factories, eventually.

I collect quite a lot of strange things. When I’m taking people around and talking to them about political intentions and so on, they pretend to understand. But in most cases, you hear them say afterwards, ‘This guy is crazy.’

Purple Hibiscus (2023–24) being crafted at Aliu Mahama sports stadium in Tamale, Ghana. Courtesy the artist/Red Clay, Tamale/Barbican Centre, London/White Cube

What’s your most well-thumbed book?

Marx’s Das Kapital is an important one – also Walter Benjamin’s text ‘The Author as Producer’ (1934) and The Making of the Indebted Man (2012) by Maurizio Lazzarato.

Who is the most interesting visitor you’ve ever had?

A tuk-tuk driver who brought tourists to my studio then had a personal tour. He was very excited about what he saw. He never knew that art like this existed. He went home, closed work for that day (as precarious as his situation was), then brought all his kids over to spend the afternoon here. There were 15 kids in the tuk-tuk! He had to put wood on the sides to prevent them falling out.

If we cannot make work that can be somehow transformative for people like him, what’s the point of art? When you go to an opening at the Tate or any big museum in a cosmopolitan city, there’s normally the same type of people there all the time. If you can shift something and change how people respond to or use art, that’s a gift.

As told to Isabella Smith.

Installation view of Purple Hibiscus (2023–24) by Ibrahim Mahama at the Barbican. Photo: © Pete Cadman and Barbican Centre; courtesy the artist/Red Clay, Tamale/Barbican Centre, London/White Cube

Purple Hibiscus (2024) is at the Barbican, London, until 18 August.