Brian LaSaga shares his secrets for realistically capturing the subtleties of snow.

By Susan Byrnes

Drift, crust, powder—there are many words to describe the characteristics of snow. In St. George’s, Newfoundland, where the average annual snowfall is 155 inches, acrylic artist Brian LaSaga can be found carefully observing these characteristics that he later translates into paintings that are spectacularly detailed. Not only is LaSaga a keen observer of snow, he’s a lifelong student of the natural environment during every season in his native province.

LaSaga’s body of work consists of intimate land, water, sky, and snow scenes that often feature elements of human presence or natural processes. Focused on the familiar, indigenous, raw, and sacred, his paintings reveal a quiet reverence for the wild and tamed, and the touched and untouched beauty of his sparsely populated surroundings.

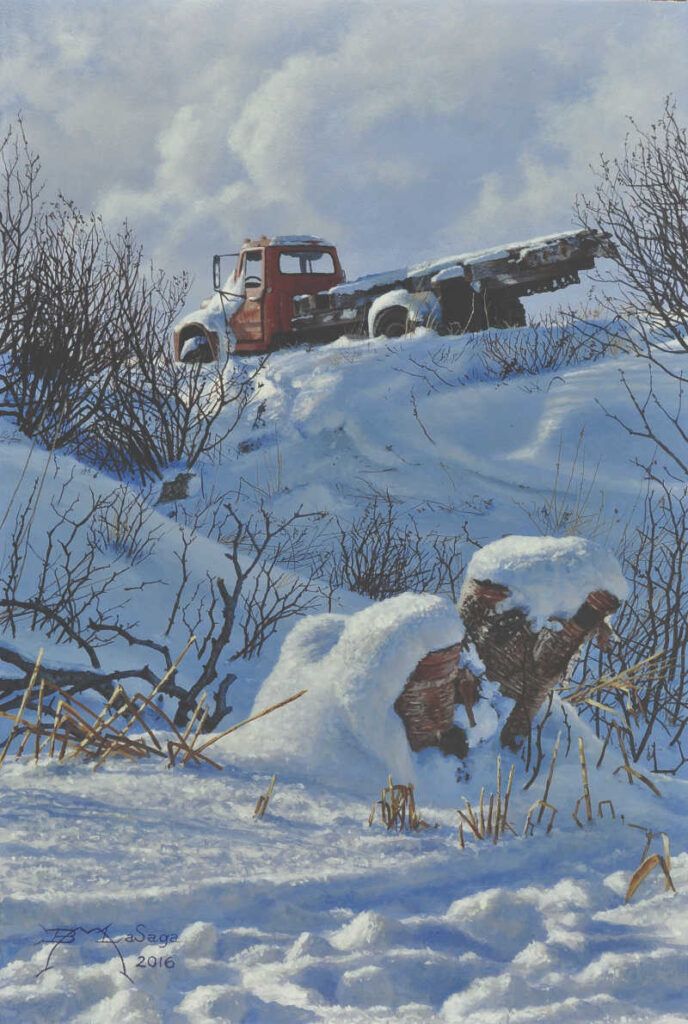

An ordinary occurrence like sunlight on snow might point out a singular moment like the confluence of natural elements as in Winter Fir, with its sunlit icicle adorning the small tree, or those in Whiskey Jack and Wood, with its side-lit woodpile and jaybird. Decaying objects such as the vehicle in Winter Relic serve as a visual counterpoint to the natural elements of snow and water.

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2016 issue of Acrylic Artist. Get the issue now—members get 30% off!

Capturing Snow

When most people think of snow, they think white, but not LaSaga. For him, snow is alizarin crimson, phthalo blue, ultramarine blue, and dioxazine purple. And yellow. “I always use yellow in snow,” he says. “I have to—very subtly—because of the sunlight.” He prefers Hansa yellow combined with small amounts of white, blue, orange, purple, and sometimes red.

For rendering shadows in his winter scenes, LaSaga uses dioxazine purple in every painting, because it tones down the yellow. To create the effect of blowing snow, as in Winter Woodpile, he paints in high key with lots of white and brushes with bristles that have been worn down with sandpaper so the paint can be scumbled, not brushed, onto the panel. Because less detail is needed to paint light, fluffy snow, he uses a softer brush so that very little detail is visible, as in Winter Relic, above. In Below the Hill, which depicts areas of frozen, dirty snow, a sharper brush is used to paint tighter chunks of ice.