At the close of any year, it’s natural to reflect on those artists who made their final exits. The sense of loss we can‘t help feeling is suffused with gratitude for all they left behind. Their memories are indeed a blessing, as the Jewish phrase of mourning has it, because their work lives on to nourish our souls.

When a theater actor or director dies, however, it is as if a color has been removed from the palette of theatrical possibilities.

The ephemeral nature of the stage is part of its power. Prospero in Shakespeare’s “The Tempest” compares actors to “spirits” who melt into “thin air” once the revels are ended. Puck in Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” likens performers to “shadows” who rise up as audiences succumb to the collective dream of theater.

Lyricist Sheldon Harnick attends the 2017 Kleban Prize for Musical Theatre ceremony at ASCAP on Feb. 6, 2017, in New York City.

(J. Countess / Getty Images)

A playwright, lyricist or composer leaves behind something indelible. All year we’ve been basking in the brilliance of Stephen Sondheim, who by the magic of revivals seems more alive two years after his death than when he was still with us. I was grieved by the passing of the brilliant Sheldon Harnick, who wrote the lyrics for “Fiddler on the Roof” and “She Loves Me,” but I can console myself by listening to the original cast albums of these shows and marvel once again at Harnick’s gift for achieving profundity through lyrical simplicity.

But how can I share what it was like to experience Michael Gambon unleashed in Harold Pinter’s “The Caretaker” at the Comedy Theatre in London’s West End or Frances Sternhagen grounding the absurd in level-headedness in Edward Albee’s “Seascape” at Broadway’s Booth Theatre other than recalling these outings from several decades ago? No video recording could ever capture the effect these performers had on an audience when they made one of their authoritative entrances.

An older generation will remember Gambon, who died in September at 82, for his role on the British television series “The Singing Detective,” while younger fans will know him as Professor Albus Dumbledore in the “Harry Potter” franchise. “Sex and the City” devotees will instantly recognize Sternhagen, who died in November at 93, as Bunny MacDougal, Charlotte York’s haughtily disapproving first mother-in-law. But to truly know these actors, one must be familiar with their theatrical roots.

Glenda Jackson attends the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 2019 Costume Institute benefit gala celebrating the opening of the “Camp: Notes on Fashion” exhibition.

(Evan Agostini / Invision / AP)

Glenda Jackson, with whom I had a few tumultuous run-ins, was a ferocious stage performer, whose last role on Broadway, fittingly, was King Lear. I wrote an appreciation of her theatrical talent when she died in June at 87. As a two-time Oscar winner (“Women in Love,” “A Touch of Class”), she has a legacy on film that is equally considerable. But Jackson in the theater was the unadulterated Jackson. The stage is where she grew into herself, under the guidance of visionary directors like Peter Brook, and it is where she challenged herself, when not in political office, by scaling the work of Shakespeare, Ibsen, Lorca and Albee.

Barry Humphries, with whom I spent a lovely afternoon chatting beside a Beverly Hills hotel pool about his alter ego Dame Edna, was a quick-witted sensation as a TV talk show host. But to appreciate the scintillating wit and improvisational raillery of the Australian hausfrau with the wisteria wig and cat’s-eye glasses, it was necessary to be within striking distance of one of Dame Edna’s gladioli, which she would fire into the audience with the same missile-like precision of one of her devastatingly funny barbs.

Australian actor Barry Humphries, dressed as Dame Edna Everage, in Sydney, Australia, in 2012.

(Rob Griffith / Associated Press)

Humphries, who died in April at 89, had something Gambon had in spades — intelligent bravura. The Irish-born Gambon, who talked his way into an acting career before he had any real training, had a barnstormer’s flamboyance and a pool shark’s delicate touch. A verbal sharpshooter, he was made for the poetic jigsaws of Pinter and Beckett, two playwrights to whom he maintained a lasting loyalty.

Caryl Churchill’s experimentalism in “A Number” didn’t throw Gambon. He could play a suave capitalist (in David Hare’s “Skylight”) or an Italian American longshoreman (in Arthur Miller’s “A View From the Bridge”) with equal alacrity. Given the gargantuan role of Falstaff in Nicholas Hytner’s production of both parts of “Henry IV” at the National Theatre, he feasted on the wit while finding room for piercing melancholy. But it was the role of Davies, the old tramp who gets embroiled in a classic Pinteresque territorial struggle after one of two brothers invites him to spend the night, that showcased Gambon’s virtuoso command.

Playwright Alan Ayckbourn, who directed Gambon in his Olivier Award-winning performance in “A View From the Bridge,” accurately eulogized his acting as a form of “spontaneous combustion.” For a performer who was so comfortably Falstaffian, Gambon was remarkably supple in his emotional range, moving from tyrannical to tender with breathtaking ease.

The last time I saw Gambon onstage was in “All That Fall,” a Beckett radio play produced off-Broadway in 2013 after its heralded London run. Irreplaceable Eileen Atkins was his co-star, and together they translated this audio drama to the stage in all its merry gallows humor. A recognizable screen star, Gambon went out not with a Broadway bang but with a sly Beckettian titter, committed as always to the work rather than his celebrity.

Sternhagen had her own dalliances with Pinter, having performed in two notable short plays in 1964, “The Room” and “A Slight Ache.” Her sturdy presence ballasted unconventional work and gave substance to the eccentric roles she was drawn to, though like Gambon she could adapt to any theatrical circumstances. Her two Tony Awards for featured actor were for plays as different as Neil Simon’s “The Good Doctor” and Ruth and Augustus Goetz’s “The Heiress,” adapted from Henry James’ novel “Washington Square.”

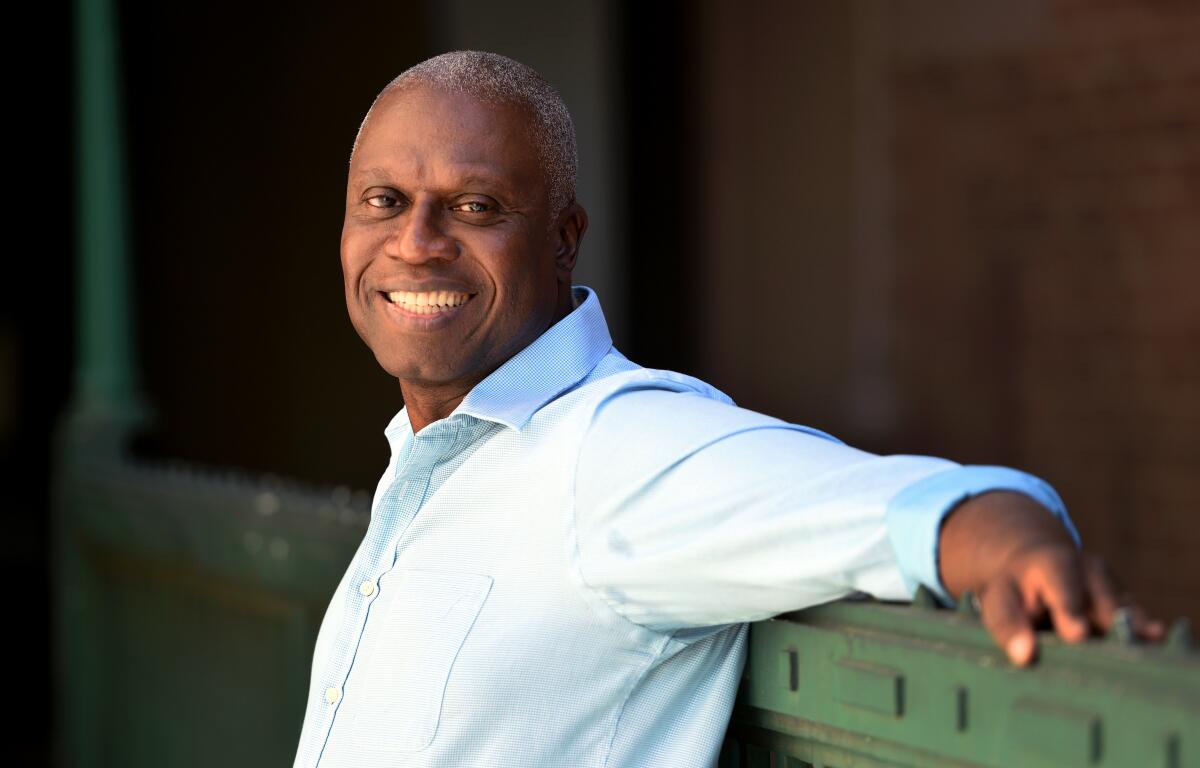

Andre Braugher at CBS Radford Studios in 2018.

(Chris Pizzello / Invision / AP)

This was not a talent to be pigeonholed, though what made Sternhagen stand out was the spine she gave to even her most vulnerable characters. Whatever craziness might be engulfing her, whether assailed by death in Terrence McNally’s “A Perfect Ganesh” (opposite Zoe Caldwell) or encountering talking sea creatures in Albee’s “Seascape,” she preserved her dignity. Sternhagen, an actor of exquisite balance, is who you wanted beside you riding out a Darwinian storm.

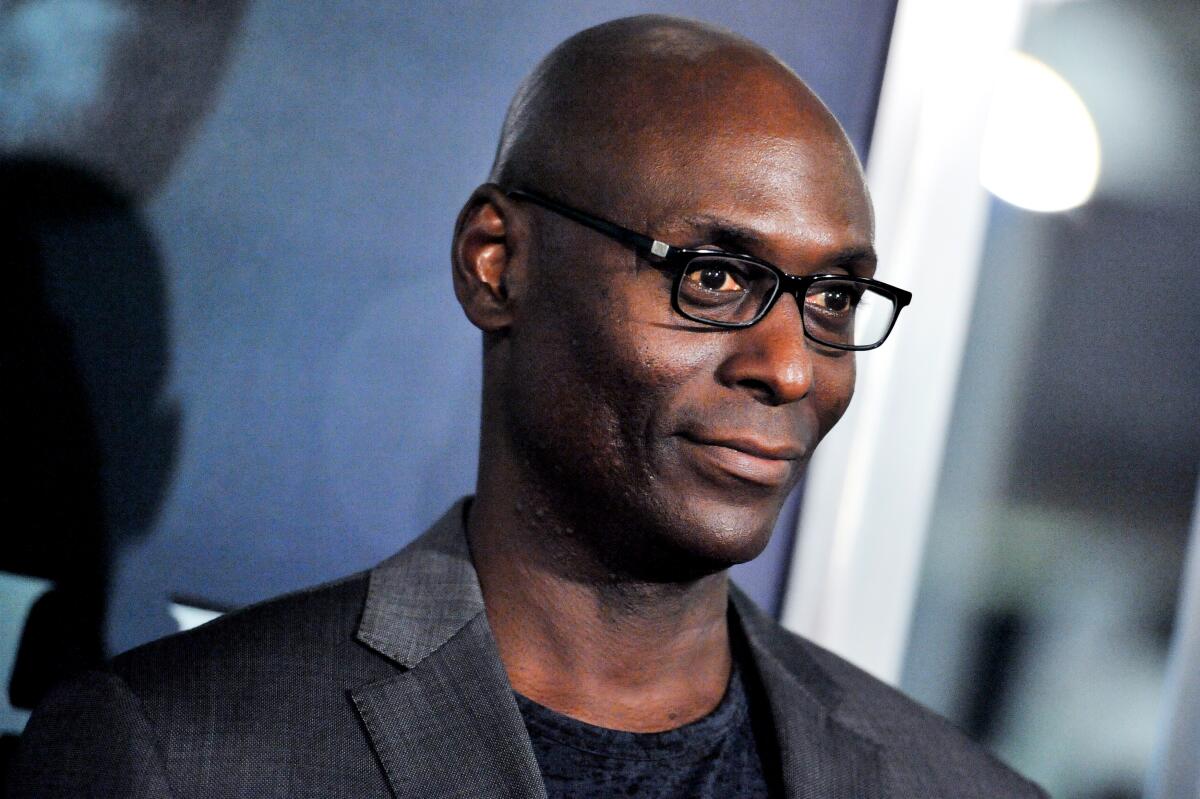

The professional longevity that Gambon, Sternhagen, Jackson and Humphries enjoyed made it possible for generations to appreciate their distinctive brilliance. That privilege was denied two notable Black actors, Lance Reddick, a classmate of mine from the Yale School of Drama, and Andre Braugher, who set the New York theatrical world on fire when he starred in “Henry V” at the Delacorte Theater in Central Park in 1996. These men died this year at 60 and 61, respectively. But their screen work will fortunately always be with us.

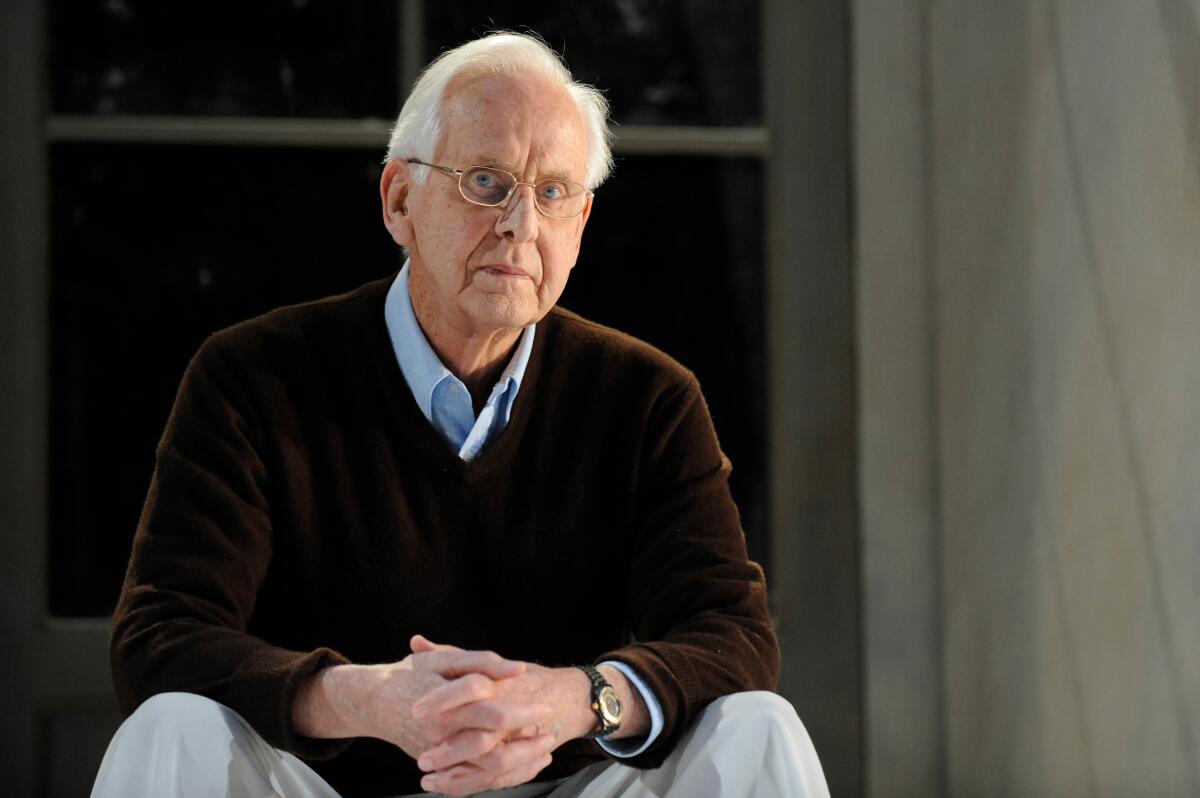

Although his name and face may not be widely known in America, director Michael Blakemore, who died in December at 95, deserves to be commemorated as much as any theater artist who left us this year. His impeccable productions were one of the reliable pleasures of contemporary theatergoing in Britain and the U.S. for decades.

I’ll never forget the summer evening in 2000 when I saw his Tony-winning revival of “Kiss Me, Kate,” starring Brian Stokes Mitchell and Marin Mazzie, because I danced all the way home after parting from the NYU students who accompanied me on this class trip — teacher and pupils similarly levitating out of the theater. That year, Blakemore had pulled off a rare coup, earning two Tony Awards for directing, one for “Kiss Me, Kate,” and the other for “Copenhagen.”

Theater director Michael Blakemore.

(Robbie Jack / Corbis / Getty Images)

The Australian-born director, who was himself an accomplished writer, had a gift for directing brainy dramas by Michael Frayn (“Democracy,” “Copenhagen”), cutting a clear theatrical path through dense historical argument. He entered the top tier of international directors in 1967 with his production of “A Day in the Death of Joe Egg,” a personal drama from playwright Peter Nichols about the parents of a severely disabled child, which blends topsy-turvy farce and tragedy to startling effect.

Tragedy and comedy were compatible in Blakemore’s productions, as they were merely different routes to the same destination: truth.

His light touch had a way of taking hold, not simply evaporating, as anyone who saw his revival of “Blithe Spirit” with Angela Lansbury that came to the Ahmanson Theatre in 2014 can attest. The dry comic genius that years later would make Maggie Smith internationally celebrated in “Downton Abbey” was baked to perfection in Blakemore’s production of Peter Shaffer’s “Lettice and Lovage,” which traveled to Broadway from London in 1990.

Lance Reddick in 2014.

(Richard Shotwell / Invision / AP)

Theater, even in an age of digital recordings, lives on in memory. The written word preserves what is otherwise fleeting. Blakemore’s killer memoir “Stage Blood” resurrects the early days of the National Theatre under the aegis of Laurence Olivier. But it was in his novel “Next Season,” which I’m always foisting on theater friends, that Blakemore managed to capture the evanescent world of the stage in all its heartbreak and glory.

If the theater, like life, is a dissolving dream, as Shakespeare proposed, these great artists who left us in 2023 helped make the “insubstantial pageant” unforgettably real.