There’s a photograph of Joy Gregory taken late last year, moments after she realises she has won the £110,000 Freelands award. Her face is a picture, expressing her genuine, jaw-dropping, oh-my-god-did-that-just-happen-I-need-a-drink levels of shock. When she heard her name, Gregory – who is best known for the photographic art she’s been making since the early 1980s – assumed it was an honourable mention, that she was just a “worthy” also-ran. “Because that’s what we always have been,” the British-Jamaican says with a wry smile as we chat in her studio.

Gregory’s work space is in the heart of Camberwell. Over the 10 years she’s been here, this part of south London has been transformed. Cranes lifting giant sheets of glass for luxury flats punctuate the skyline of neighbouring Elephant and Castle, while competition for housing is fierce. Gregory, 64, has just rented out her nearby flat and had a staggering 500 applicants. During the same period, the art world’s opinion of artists like Gregory – Black British women – has also shifted dramatically. Suddenly, they’re hot property.

The last decade has seen a long line of formerly marginalised female Black British artists and writers finally given their due as they enter middle age. First Lubaina Himid won the Turner prize at 63 in 2017; then Bernardine Evaristo won the Booker two years later; other Turner nominations followed for Ingrid Pollard and Barbara Walker. Meanwhile, Helen Cammock and Veronica Ryan have both won the Turner since Himid – and Liz Johnson Artur was one of the recipients of a bursary in 2020, awarded in place of the cancelled prize. As we talk, there’s a major retrospective of Claudette Johnson’s work at London’s Courtauld, while in 2022, another contemporary of Gregory – Sonia Boyce – won the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale.

“Those people have always been there, but there’s been no light really shone on them,” says Gregory, adding that, as a photographer, the odds were even more stacked against her as a young artist in the 1980s. “When I left college, the director of Tate [Alan Bowness] said photography would go into his collection over his dead body, because it’s not an art form. And then to be of colour as well … ” But now Gregory’s name can be added to that list: as part of the Freelands prize (of which Gregory receives £30,000), London’s Whitechapel Gallery will host a mid-career retrospective for Gregory in 2025.

Gregory grew up in Aylesbury, the Buckinghamshire county town. “If you’re a person of colour in a place where it is essentially completely white, the attention is there all the time,” says the artist, who was a shy, dyslexic girl. She spent her childhood “trying to disappear”, a task that was easier said than done in a town with just a few Black families. “Every time you do anything, it’s always about being representational of a people rather than being representation of yourself.”

Art provided an escape: her family home was close to a printing company, where she would spend long summer days leafing through books that had been deemed defective and discarded. It was these sessions, where she would read writers such as Nell Dunn – combined with access to her school darkroom – that set Gregory on a path towards the arts and photography.

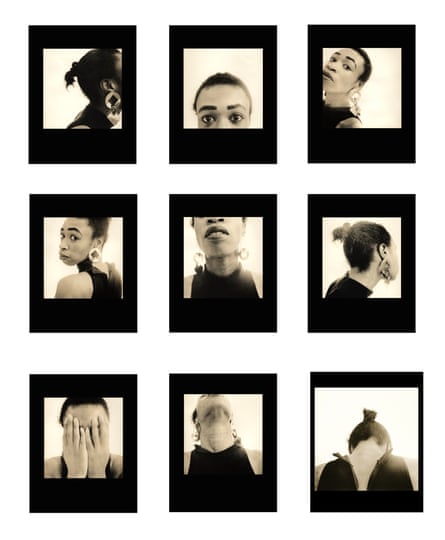

Perhaps fittingly for someone who tried so hard to fade into the background, Gregory’s work is often about what is seen and what isn’t. Her best known image, Autoportrait, sits above the fireplace as we talk. It’s a series of nine self-portraits where Gregory strikes poses: looking down the lens, over her shoulder, and straight up so we see the detail of her neck. The lack of Black models in the fashion magazines she loved (Gregory dreamed of working at Vogue when she was young and once applied to work in Condé Nast’s darkroom) partly inspired Autoportrait. It’s typical Gregory: playful and approachable or, as she likes to say, “seductive”.

This is a quality she puts down to taking a commercial photography course at Manchester Polytechnic in the early 1980s, where she lived in the notorious Crescents housing development in Hulme. Gregory learned the technical aspects of photography there, including how to use cyanotype prints which are made by lying objects on treated paper before exposing it to UV light, triggering a reaction that creates a brilliant blue image. Gregory went to the Royal College of Art afterwards, studying under John Hedgecoe, who took portraits of the Queen, worked for Vanity Fair and was Britain’s first professor of photography.

Other works dotted around her studio tell the story of her evolution as an artist. There’s the series Cinderella Tours Europe, where she took pictures of famous backdrops, like the 110m tall Christ the Redeemer statue in Lisbon and the canals of Venice, with a pair of gold shoes in the foreground, representing those from the former colonies who were brought up to know all about European history but who would never be able to visit the continent.

By the early 2000s, her work had shifted from self-portraits to long-term collaborations with underrepresented groups who fascinated her. Memory and Skin, her first major solo exhibition, featured interviews and images of people she met in Cuba, Haiti and her parents’ homeland: Jamaica. It took years to assemble and played with the legacy of colonialism, showing how links between the Caribbean, Britain and other European countries shape contemporary life. Some of her projects take even longer: she’s currently 20 years into working with a group from the Kalahari Desert in South Africa, who are the last speakers of the dying N/uu language.

Looking at her work now, most people would say it fits into the world of Black Art that emerged in the 1980s – politically tinged, tackling issues of colonialism and slavery. But during the Thatcher-era, Gregory’s work – which was always subtler than say the collage work of Eddie Chambers, which combined the union jack and a swastika – wasn’t considered “Black enough”. She remembers sending her work, images of fauna and flowers, for consideration in a Black photography exhibition only for it to be rejected. “I was a bit cross at the time. I was thinking, ‘What do you mean it’s not Black enough?’ But then it was about fitting within a particular framework of what Black visual art could be.”

after newsletter promotion

She goes on: “They were building their own prison, in a way. The whole point of me being able to do my practice was having the choice to do what I wanted, not what someone else dictated I’d be allowed to do. People like me have been told what they’re supposed to be doing for generations; I wasn’t going to carry on with that.”

Gregory seems to take delight in challenging expectations of her. When an institution in Barcelona asked her to contribute to an exhibition about Black presence in Europe, she knew the organisers wanted her to “take photographs of Black people shopping at Brixton market”. Gregory had other plans. She produced images of East India Dock and Kennington Common – sites around the capital that were key locations of Black London’s history. There wasn’t a carrier bag in sight.

While she welcomes the recognition that the Freelands prize brings, Gregory says it’s not the praise she values most highly. That comes from students, such as the young artist she taught at Slade, who recognised her and said she’d always wanted to meet her. “It’s a bit like being an underground person,” says Gregory. “People know the practice, but I’m not one of those people who’s got a gallery.” (She was briefly represented by Zelda Cheatle in the 80s.) Although that might soon change.

Gregory has just signed on to produce work for Heathrow’s Terminal 4, for which she’s been working with asylum-seekers kept in hotels near the airport. Her work is also currently appearing on London Underground maps: a floral print called A Little Slice of Paradise, inspired by the mini gardens staff cultivate at stations around the capital. In the week leading up to our interview, I try half a dozen stations but can’t find any. Gregory tells me they’re now all over eBay – another sign her work has reached a critical mass. “My niece,” she says, “has been down at Bond Street, harassing the station staff trying to get one.”

The recognition, the awards and the greater platform are all welcome, but you get the sense Gregory would be happy continuing to work as she has done since the 1980s – on her own terms and in her own way. She’s not making art for the prizes. “It’s something I’m compelled to do,” she tells me. “I have to make pictures.”

That desire touches all parts of her life: after we speak, Gregory tells me she’s going to spend the rest of the day constructing a photo album as a birthday present for her sister. Is she going to use cyanotype, I ask, imagining some complex semi-industrial process. “No,” she says. “I’m going to Snappy Snaps.”