Like dance, figure skating blends both athleticism and creativity: Skaters perfect highly technical maneuvers like triple Axels and upright spins, often while weaving a narrative into their programs. To develop the lines, control, and artistry needed to execute a winning program, many competitive skaters rely upon the skills of dance coaches and choreographers.

There’s a common misconception that experience on the ice is a prerequisite for working with skaters. But for many dancers who have transitioned into coaching and choreographing for skaters, the skills that they bring to the rink are exactly those they’ve honed in the studio and on the stage: body awareness, proprioception, musicality, and expressivity.

Breaking the Ice

Ginette Cournoyer, a former Canadian and North American ballroom champion who has been working with skaters for 33 years, first started training skaters at her dance school. Later on, Skate Canada approached her about working with ice dancers on their rhythm dance (the first segment of an ice dance competition). She choreographed for Olympians Marie-France Dubreuil and Patrice Lauzon; when they later founded the Ice Academy of Montreal, they asked Cournoyer to join their team as a dance coach. Cournoyer has since choreographed for several Olympic and world ice dance champions, such as Canada’s Tessa Virtue and Scott Moir and France’s Gabriella Papadakis and Guillaume Cizeron.

Jimmie Manners had just left a three-year gig dancing in Jennifer Lopez’s Vegas residency All I Have when Elena Novak, from Ion International Training Center in Leesburg, Virginia, reached out. The International Skating Union had announced that for the 2021–22 season, the theme for the rhythm dance was street dance, and Novak was searching for a choreographer with professional experience. “I didn’t even know ice dance existed,” says Manners, who received a crash course in the sport and is now a certified coach and head of choreography at Ion.

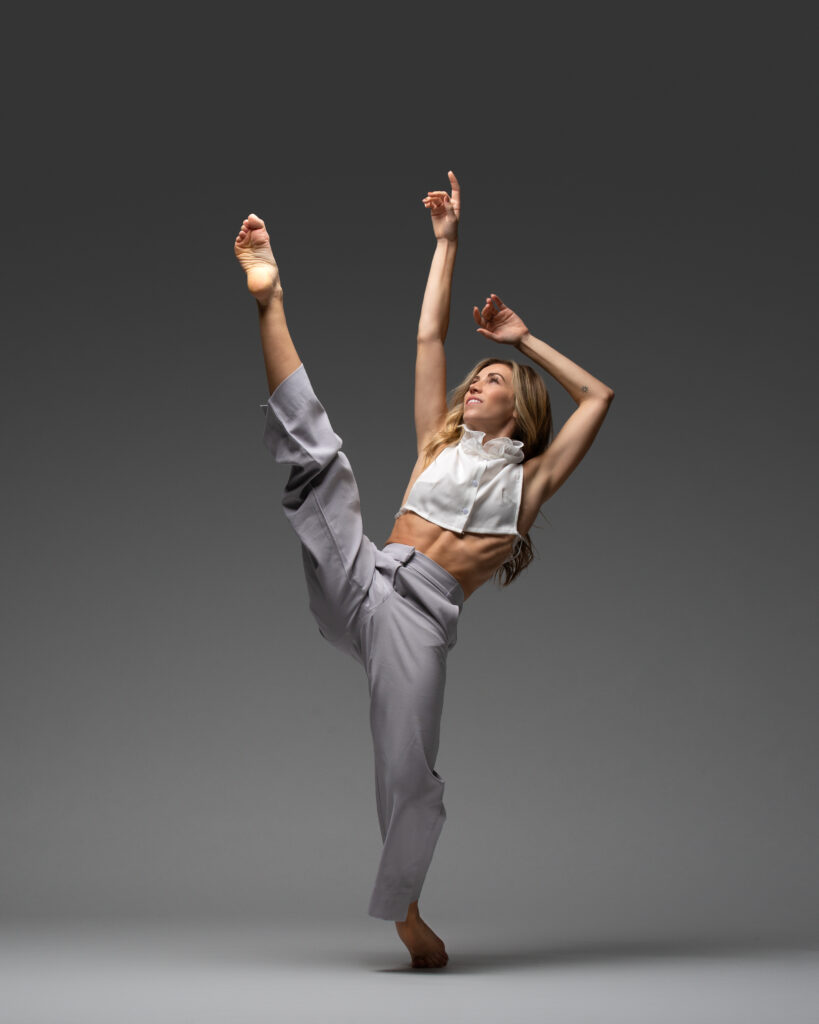

Brooke Mainland, a company member with Eisenhower Dance Detroit, who acknowledges she “can barely skate forward,” is the off-ice dance coordinator for Detroit Skating Club. Mainland began working with skaters in 2018, fell in love with the sport, and has been coaching skaters in dance technique and Pilates ever since.

A Learning Curve

Working with skaters required Mainland, Cournoyer, and Manners first to understand what is—and isn’t—possible on ice. “If you want skaters to go the opposite direction, it doesn’t work the same way that it would on the floor,” says Cournoyer. Complicated foot patterns and floorwork also don’t translate easily to ice.

As different as dance and skating are, there are many ways skaters can learn from dancers. Strong arabesques can translate to solid spirals; finding stability in the supporting leg after a tour jeté can be similar to landing a double Axel safely; and maintaining extensions and flexibility helps skaters find success with their spins.

When leading off-ice dance classes, Manners includes coordination exercises with polyrhythmic tempos to simulate performing skating steps like crossovers or stroking while simultaneously using flowing port de bras. He also teaches combos to help develop musicality; currently it’s all about the ’80s, which the International Skating Union announced must be included in the rhythm dance next season, so Manners is teaching to Prince, Michael Jackson, and Madonna.

Building a Program

When creating a new program, choreographers start working with skaters in a studio, developing upper body movement and exploring different shapes. “Once we get on the ice, it becomes more of a collaboration with the skater,” explains Mainland, who likes to experiment with how turns or traveling steps can be impacted by the skater’s arms being held differently.

When the foundation of the program is set, skaters will continue to work on the dance elements while also applying technical corrections to the skating elements, such as jumps and spins. Most choreographers collaborate with trained skating coaches, to make sure that all the required technical elements are included in the program. A large team of skating, acrobat, acting, and dance coaches (including experts in ballet, ballroom, and hip hop) might collaborate to strengthen a single program, and continue to work on it all year. “We’re never finished until the World Championships at the end of season,” says Cournoyer.