From the December 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

A photograph of Marisol (1930–2016) taken by Robert Mapplethorpe in 1979 shows the artist in a curious outfit. Her clothes are those of an artist in her studio: a hoodie, thermal shirt and jeans dirty from the week’s work. But on her head she’s affixed a light-coloured, satiny fascinator, with a feathery tuft and a veil that envelops her head, like a net enclosing a fish. The mismatched ensemble is no doubt intentional, but how to interpret the combination? Is it an illustration of dual or duelling identities? Of external expectations – roles that have been thrust upon her? Her gaze at the viewer is direct, her expression does not hedge. To make sense of the image feels like a dare.

Marisol (1979), Robert Mapplethorpe. Buffalo AKG Art Museum, New York. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission

Mapplethorpe’s photograph is one of several at the start of the catalogue that accompanies a retrospective of Marisol’s 60-year career, curated by Cathleen Chaffee of the Buffalo AKG Museum and currently at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (until 21 January 2024) before it travels to other venues. It is a fitting image to introduce an artist whom critics and others imagined as an enigma, who was said to have ‘disappeared’ from the art scene and yet who never stopped making an astonishing array of art that was frequently moulded from her own body.

In the early 1960s, she described her sculptural process in an artist’s statement for the Stable Gallery: ‘I like to make combinations that seem incongruous – wood with plaster – pencil drawing on wood but finally I put things where they belong – a hand at the end of an arm – a nose on the middle of the face – a hat on top of the head – a shoe on a foot – a foot on a leg – a breast on a woman’s torso – a mouth with a little below the nose and a nostril inside the nose.’ Marisol’s method is instructive for understanding the complexity of her identity as well: the elements may be collaged and the form presented with caesuras, but in the final moment, she knew how each of the pieces should align.

She was born María Sol Escobar in 1930, in Paris. Her parents were wealthy Venezuelans and the family travelled extensively throughout Europe. By the mid ’30s, they mainly divided their time between Caracas and the United States; young Marisol read American comics and Italian fumetti and drew pictures of the saints she learned about in Catholic school. Her mother committed suicide in 1941 and Marisol, who toggled between schools in New York and Caracas, stopped speaking. ‘I didn’t want to sound the way other people did,’ she later explained. ‘I didn’t really talk for years except for what was absolutely necessary in school and in the street […] I was in my late 20s before I started talking again.’

In 1946, she moved with her father and older brother to Los Angeles and María Sol became Marisol, a nickname given to her by her mother and a portmanteau of the Spanish words for ‘sea’ and ‘sun’. Her early art training was a hodgepodge of night studies at the Otis Art Institute and the Jepson Art Institute in LA, painting lessons at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and classes in painting, sculpture and ceramics at a host of New York schools and with individual instructors, including Hans Hofmann. She had come to New York on her own, traveling across the country by bus in 1950; the city was then the domain of Abstract Expressionism and the New York School and Marisol befriended a host of artists, among them Willem de Kooning, Frank O’Hara, Alex Katz, Ruth Kligman and William King.

During this period, Marisol began working with wood, though her formal training in woodworking was likely minimal at best. In 1955, she made The Hungarians, a portrait of four weary refugees carved from wood and set atop a wheeled metal cart, as if at any moment they might be transported away. It was one of the first instances in which she used a found object in her art and vulnerability was a subject that would recur throughout her career. At the same time, she made small bronze and terracotta compositions, often crowds of acrobatic figures arranged in dynamic towering heaps. She positioned some of these on the shelves of large printer’s boxes, where they resemble reliquaries or Louise Nevelson’s contemporaneous reliefs of stacked found objects. (In the early 1950s, both Marisol and Nevelson saw examples of pre-Colombian art that significantly influenced the development of their work.)

Tea for Three (1960), Marisol. Buffalo AKG Art Museum. © Estate of Marisol/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Marisol’s solo debut came in 1957, at Leo Castelli Gallery, where she showed wood sculptures, polychrome reliefs and terracottas. The show’s success spooked her and she took off for Rome. After 18 months, she made her way back to New York, stopping at the East Hampton home of the artists Conrad Marca-Relli and Anita Gibson. There, she found a bag containing hat forms. ‘I was really lost,’ she said of that moment. ‘And then I found these wood hat forms and I decided to make sculptures out of them with faces and lots of colour.’ Her art was revolutionised by this discovery. In 1960, she made the sculpture Tea for Three, using the forms as a trio of ornamented heads atop a rectangular body set on rockers and painted the colours of the Venezuelan flag.

Over the next decade she produced a startling number of such sculptures, made with varying combinations of wood pieces, found objects, plaster elements, acrylic, graphite and other material. In every case, her sculptures are far more than the sum of their parts and they evoke a range of perspectives and feelings, engaging with politics, pop culture, caricature and social hierarchies. In The Bathers (1961–62), three women sunbathe against a field of bright blue that rises vertically against the wall. The plaster casts of their hands and feet – and in one case, buttocks – are pink adornments on their wood bodies. The upper body of one woman is rendered in two dimensions on the wall, while her legs emerge into three dimensions, a big toe jutting blithely into the air. The Generals (1961–62) depicts Simón Bolívar and George Washington sitting closely astride a horse whose legs are mounted on casters. A hole in the horse’s ass emits a jaunty military tune on a loop. It was the height of Cold War tensions between the United States and Latin America (the Bay of Pigs invasion and the Cuban Missile Crisis occurred in 1961 and 1962, respectively) and Marisol’s assemblage makes toy soldiers of these two founding fathers, with, as Delia Solomons has argued, homoerotic undertones.

The Bathers (1961–62), Marisol. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville. Photo: Edward C. Robison III; courtesy Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art; © Estate of Marisol/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Rather than carving into the wood, Marisol found material that imparted the spirit of the form she wished to create. The cuboid shape of many of her figures’ bodies from the ’60s resembles a canvas extended forward in space, as if separating from the wall and entering into the room. They are canvases that have become fully three dimensional, with arms and legs that allow them to move about and interact with the world. Only when Marisol adds embellishments and graphite drawings to the wood itself do the blocky forms become gendered. Breasts and testicles become ornamentation, like sunglasses or jewellery.

Many of these figurative sculptures contain at least one mould of some part of her own body, most often her face and frequently multiple versions of it. She claimed that the moulds were made out of convenience – she was always available to herself as a model – but by integrating herself into a sculpture, Marisol explored what she called ‘an experience from life’. In an interview with the art historian Cindy Nemser in 1973, she said, ‘I like to do lots of different things. So at one point I was like a beatnik; then at one point I wanted to be a society girl; then a diver, a skier.’ Marisol’s face appears on four of the half dozen heads in Six Women (1965), which are distributed in pairs on three rectangular freestanding bodies. The bodies are linked to one another by mirrors that make up the right sides of two of the rectangles, so that the torso and legs painted on the side of the adjacent body are doubled by its neighbour. In effect, all six women represent a single figure, slowly changing as if on a continuum.

Marisol’s work from this period is remarkable in part because it doesn’t fit neatly into any category to which it ought to belong. In 1964, Brian O’Doherty situated her alongside Robert Rauschenberg, George Segal and Tom Wesselman – New York-based artists who combine objects from daily life with painted or sculpted elements, where ‘each partakes of the other’. And yet the large, textural, collaged bodies and figurative focus of so many of her sculptures resonate with much contemporaneous Bay Area art: the rough monumentality of Viola Frey’s ceramics, Robert Arneson’s multivalent self-portraits and the paste-up juxtapositions of Jess.

In 1962, Marisol met Warhol and fell in with the downtown scene. He cast her in several of his films and she made a sensitive and vulnerable sculptural portrait of him. Her social engagements with celebrities, art stars and wealthy socialites earned her a reputation as a party girl, which in turn coloured assessments of her art. Warhol was right to deem her ‘the first girl artist with glamour’. Her presence – that je ne sais quoi or aura – proved irresistible to critics, although they didn’t engage with the complex grammar of Warhol’s conception of ‘glamour’. There was sometimes more than a whiff of sexism. She was called a ‘Latin Beauty’ (Life) and ‘sensual señorita’ (Playboy). According to Time, she was ‘a black-haired, wide-eyed unmarried woman of 33’ – practically feral.

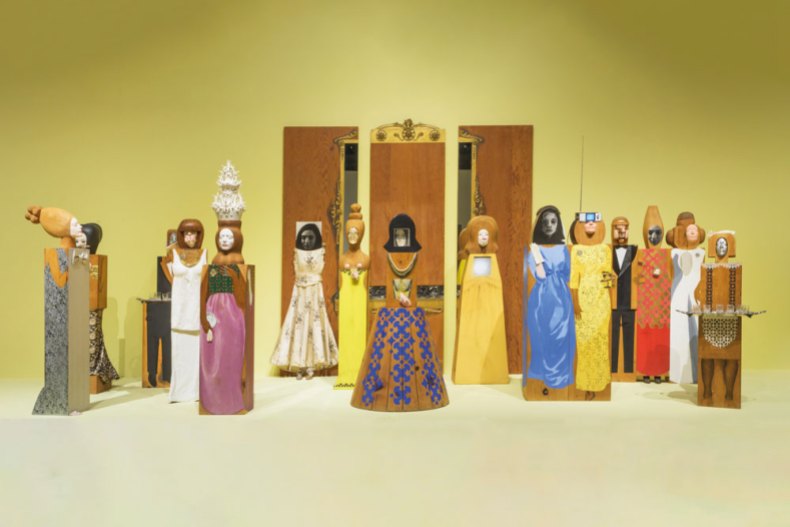

Marisol’s art, on the other hand, suggests boundless latitude: her face could appear anywhere; she could be anyone. The Party (1965–66) may be her most ambitious work. The elaborate assemblage comprises 15 freestanding, life-size figures and three panels set against the wall, fitted with the edges of a large mirror and, on one end, with a real dress and an image of a woman’s (Marisol’s) face. The figures are arrayed as if at a cocktail party and are dressed in evening gowns, save the male and female pair serving drinks and a single male guest in tuxedo. All bear images of Marisol’s face. One figure has a lightbox installed in her chest, illuminating a picture of a Harry Winston diamond necklace. On another, a picture of a drink is collaged on to one side of her wood torso, while a man’s hand reaches across from the other side toward her breasts, which have been moulded from grapefruits. A third has a small television in place of her face, but the screen displays only static. None of the figures interact; each is her own island. Does the television tuned to a dead channel signify this disconnect? Or is that particular woman simply checked out? In the catalogue, Jessica S. Hong reads the entire tableau as a ‘performance of the ideal middle-class version of an American family, one familiar from popular programs of the era such as Leave It to Beaver (1957–63) and The Donna Reed Show (1958–66)’. The Party has an undeniable allure. When Marisol showed the work at Sidney Janis Gallery in 1966, 3,000 people reportedly stood in line to see it.

Installation view at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in 2023 of The Party (1965–66) by Marisol. Photo: MMFA; © Estate of Marisol/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In 1968, Marisol represented Venezuela at the Venice Biennale. Afterward, she travelled to India, parts of South East Asia and Tahiti, where she learned to scuba dive. The United States was embroiled in the Vietnam War and she had sought to escape the violence at anti-war protests back home. In the ocean, she found a reprieve. She made photographs and films of sea life, intending to make a documentary that would, in part, show ‘how it feels to flow with water’, implying a wonderful sense of belonging.

Her shift toward aquatic subjects resulted in fluid sculptures, which she shaped from mahogany and lacquered with multiple coats of varnish. She sculpted lithe needlefish, barracuda, parrotfish and triggerfish and attached translucent moulds of her face on to their heads, creating animal-human hybrids with gaping mouths. She chose aggressive species that were also used to name Navy vessels. ‘At one point I thought I was making weapons,’ she said, ‘because I had these skinny long pieces and they were aiming out of the window like missiles’. Of Lee Bontecou’s spiky, armoured aquatic sculptures, which she also began making in 1969, the poet Tony Towle wrote, ‘They are less animals than they are the quality of being an animal’ – an observation that applies to Marisol’s hybrids, too.

She debuted her marine work at Sidney Janis in 1973. Critics panned the show. Peter Schjeldahl thought Marisol’s use of her own body was narcissistic and overall he found the work to be ‘too delectably wrought’ to evoke the ‘instinctual […] primordial urges’ they express. They amount to no more than ‘a unique class of significant curios’, he concluded. Hilton Kramer thought it passé, writing, ‘This gifted artist, once so promising, looks more and more like a permanent casualty of the Pop movement.’ When John Perreault wrote disparagingly of her ‘neo-sophisticated appropriation of folk-art forms,’ Marisol responded in a biting reply, never delivered: ‘Folk you.’

Triggerfish II (1972), Marisol. Buffalo AKG Art Museum, New York. © Estate of Marisol/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In the ’70s Marisol initiated several groups of work in disparate mediums: sets and costumes for dance performances; large coloured pencil drawings; and wood portrait sculptures. Between the 1970s and 1991, she collaborated with Martha Graham, Louis Falco and Elisa Monte on nine stage productions. Her earlier sculptural figures were translated into bodies in motion and constantly shifting relationships between bodies and the forms used for sets and decor. For Falco’s production of Caviar in 1970, for instance, she created large foam-rubber sturgeon, which leaping dancers carried across the stage, held aloft and tossed into the air in an undersea fantasia.

Her drawings from this period focus on hands, feet and bodies rendered in a maze of line and a riot of colour. One body becomes indistinguishable from another and gender is frequently indeterminate. Marisol confounds the eroticism of a tangle of figures dressed in rainbow shades with troubling suggestions, through titles (I Hate You Creep and Your Fetus) and violent imagery. In reducing her figures, she draws attention to the parts of the body linked to speech, communication and language. For the lithograph Cultural Head (1973), she traced her hands in overlapping layers that radiate outward from her head, like antennae. In place of a mouth, she wrote her name and the word is both the organ of speech and language itself. The hands, symbols of making, become the way she perceives and makes sense of the world.

The portraits that Marisol also began making in the ’70s occupied her through the ’90s. She made sculptures of subjects that were of political and cultural import to her – formidable portraits of Bishop Desmond Tutu and the native photographer Horace Poolaw, images of child hunger and the disenfranchised – and of artists and writers who held intimate significance for her, including Nevelson, Marcel Duchamp, Picasso and William Burroughs. In one of her portraits of Georgia O’Keeffe, she used casts of her own hands for the painter’s, creating a poignant link between the older artist and herself. Marisol made an affectionate portrait of her father in 1977. His face is rendered in bas-relief with a protruding nose and she has added a small quartz pebble as a pin on his tie. The starched crease in his pant leg echoes the soft lines and shadows in his face. Though Marisol still depicts her figures in the manner of a collage – her father is a head and torso, with disjointed legs and a hand resting on the arm of his chair – her subjects’ personalities and humanity are evoked by the fragmentation and the contrasting softness and rough-hewn quality of her woodwork. In both her sculptures from the ’60s and these later pieces, Marisol shows a deep sensitivity for her material, whether in the incorporation of a wood’s grain into the painted surface or in her ability to elicit precision and plasticity at once.

In the last years of her life, she suffered from Alzheimer’s and was unable to continue producing art at the same rate. But she never gave up on it. She relied on drawing, which had carried her throughout her long career, making portraits of her friends and caregivers and ecstatic, colourful compositions of hands, faces and patterns. When she died, at the age of 85, the Guardian announced her as ‘the forgotten star of Pop art’, a phrase that radically reduces a multifaceted six-decade career into a single era. It recalls the critical response in the ’60s to her so-called mystique, which she thought was ‘a way to wipe me out’.

Though Marisol did become increasingly obscure, it was not because she made fewer works, as the Guardian claimed. On her death, she bequeathed a significant portion of her output to the Buffalo AKG Art Museum: hundreds of sculptures and works on paper and thousands of photographs, slides and films. The ongoing examination of her archive has revealed huge gaps in the scholarship around the work. Until the publication of the retrospective catalogue, there has been little to nothing, for instance, on her aquatic period, mid ’70s feminism, dance collaborations, explorations of sexuality and gender and her sense of herself as an immigrant artist. Even as critics assessed her art in view of her physical appearance (‘What beautiful women do you identify with?’ O’Doherty asked her), she would not be closed off. ‘There comes a point where you start asking, “Who am I?”’ she told Nemser. ‘I was trying to find out through my sculpture. That’s why I made all those masks and each one of them is different. Every time I would take a cast of my face it would come out different. You have a million faces.’

‘Marisol’ is at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts until 21 January 2024, then travelling to other venues in North America.