Happy New Year. I like the number 2024. It almost looks like 2+2=4. Common sense. Hopefully there will be more of that, all around, this year than last year.

In dance, numbers matter. I’m thinking of two choreographers whose brilliant use of numbers are very different: George Balanchine and Trisha Brown. What prompted me to notice this was two recent events: The latest issue of Dance Index, and the creation of Trisha Brown Company’s Vimeo page. In the first, Jed Perl mentions Balanchine’s use of numbers as an inspiration for some of Arlene Croce’s writings featured in that issue. The second has posted several pieces and excerpts of excerpts that illuminate Trisha Brown’s math.

For both choreographers, the math helps the audience make sense of the work, and it helps the dancers stay connected to the other people onstage.

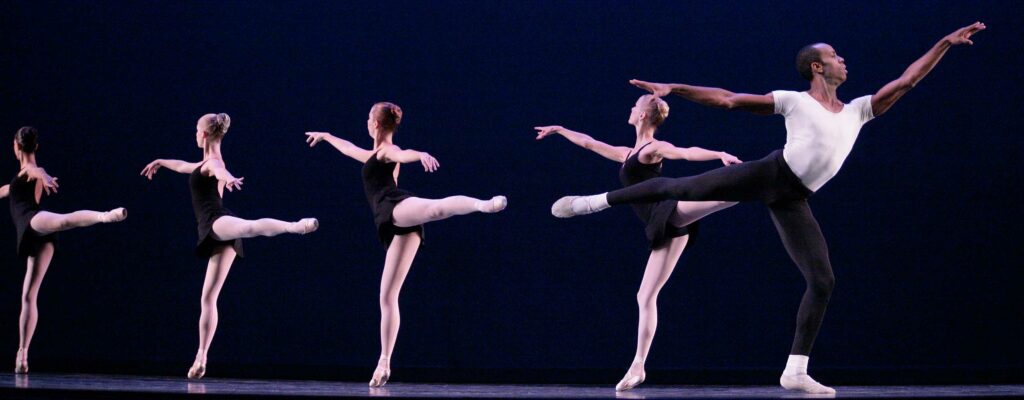

In Balanchine’s Stravinsky Violin Concerto (1972) each of the 4 soloists introduces themselves with an entourage of 4 dancers. Each star has their own constellation—or backup group. Four tight groups of 4, and one spread-out group of 4 (the leads). The 4 leads break into 2 and 2, one exquisitely modernist duet after the other. The corps of 16 (8 women and 8 men) breaks into 4 groups of 4, or 8 couples. They never all do the same steps until right near the end, and then, suddenly, for the very last position, they all break into couples—just to remind you that you’ve been watching 10 x 2 = 20 people.

In La Valse (1951), naturally the unit changes to 3. (After all, it’s a waltz.) It starts with 3 women in elegant Karinska gowns. Later a man partners 3 women at once (shades of Apollo). The corps of 24 is sometimes divided into trios, and of course the timing is in 3/4. And the woman in white is caught in a triangle between her lover and the death figure.

Balanchine famously said, If you don’t like the dancing, you can close your eyes and listen to the music. Well I say, If you don’t like the dancing, you can keep your eyes open and count the math.

For Trisha Brown, the Accumulation series is not only about numbers, but also about how we learn. We go back to the beginning each time and add something new. Trisha made her first Accumulation in 1971. She stands in silence and begins her 1st move, extending her right thumb outward, just like a hitch-hiking gesture. After a while, she adds the 2nd move, which is both thumbs extending outward. With the thumbs constantly going, she intersperses a dropped arm, a sinking hip, a head turn. Since she repeats each addition a few times, whenever the new move comes, you notice it. (Click on Accumulation on the Vimeo page.)

Brown’s Group Primary Accumulation (not yet posted on the Vimeo page) is a more explicit counting dance, structured like “The 12 Days of Christmas.” In it, 4 women gradually accumulate 30 moves while lying down, not even seeing each other until movement # 13. In order to stay together, they have to feel the group rhythm as they are counting. Their concentration is intense, which makes the audience concentrate too. When we are counting along with the dancers, we’re involved in a physical memory game.

Tamara Riewe, Melinda Myers, and Judith Sanchez Ruiz, in a screen grab of Glacial Decoy, set design and costumes by Rauschenberg

In Glacial Decoy (1979), 2 women perform together for a while. Then a 3rd enters from the side, joining them in near unison, then a 4th, creating the illusion that there are even more dancers extending laterally, beyond the wings. It’s hard to count the dancers because they keep drifting in and out. Meanwhile there are definitely 4 frames of Robert Rauschenberg’s photographic images upstage that keep changing. Whereas the number of dancers is destabilized, the number of frames, even as the images shift to the next frame, is stable. (Click on an excerpt of Decoy on the Vimeo page.)

Watching these math-rich ballets, you can meditate on the numbers. I feel that our arithmetic brain is stimulated simultaneously with the art brain. They require a multi-layered alertness from us.

Both Balanchine and Brown have made many ballets rich in math. I invite you to enter your own favorite numbers dances, from either of them or any other choreographer, in the Comments below.

Group Primary Accumulation (1972) ph Babette Mangolte, design from Columbia conference on dance history titled Accumulation