Dan Wagoner, who danced with Martha Graham, was an early member of the Paul Taylor Dance Company and led his own well-regarded troupe for 25 years, died on Friday in Oakland, Md. He was 91.

His death, in a nursing home, was confirmed by his sister Hannah Sincell.

Mr. Wagoner was a child of small-town Appalachia for whom the idea of going to New York City, he once said, was like “going to the moon.” But New York was where, starting in the late 1950s, he built a successful career as a dancer and choreographer, working with several central figures of American modern dance.

He performed in the Martha Graham Dance Company from 1957 to 1962, and again briefly in 1968. From 1960 to 1968, he danced in the troupe formed by Taylor, a fellow company member. And from 1969 to 1994, he led his own group, Dan Wagoner and Dancers.

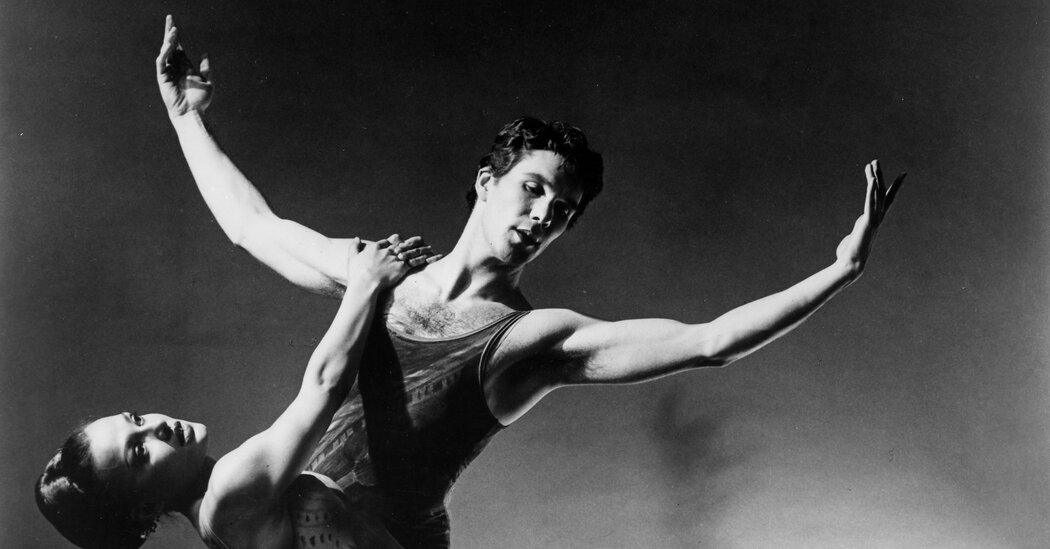

According to Taylor in his autobiography, “Private Domain,” Mr. Wagoner took on the persona “of being a bumpkin in the Big City for all it’s worth.” Taylor described Mr. Wagoner’s dancing style as “stalwart,” moving “with weight from a thick core,” and praised his facility with “tongue-twister coordinations.” Critics likened Mr. Wagoner to a sweet-spirited cherub or a crinkly eyed teddy bear.

“He is a master of quirky invention, of the odd shape, the unexpected movement,” the critic Anna Kisselgoff wrote in a 1984 review of his company in The New York Times, remarking on the “fantastic amount of energy” in his work and “the good plain fun.”

Many critics noted the influence of Graham, Taylor and Merce Cunningham, in whose company Mr. Wagoner also briefly danced. “But the way he combines, for instance, fragments of Martha Graham’s technique with Paul Taylor’s characteristic postures, topped by a nonsequential approach to linking the steps that derives from Merce Cunningham — all this contributes to a form of originality,” Ms. Kisselgoff wrote.

Thematically, much of Mr. Wagoner’s early work drew on his Appalachian upbringing: His first piece was called “Dan’s Run Penny Supper,” while another, “Summer Rambo,” was named after an apple. “A Dance for Grace and Elwood” was dedicated to his parents, and “’Round This World, Baby Mine” was set to country music.

Several of his dances, like “Changing Your Mind,” “Otjibwa Ango” and “Pemaquid,” drew on Native American culture and stories. “George’s House,” a video dance he made for Boston public television in 1975, was set in and around an 18th-century cabin. Another piece was accompanied by a recitation of his family recipe for pancakes.

The lighting designer Jennifer Tipton, a longtime friend of Mr. Wagoner’s who worked on many of his productions, once told Dance Magazine that “what is so extraordinary about Dan is the complexity of his form and the simplicity of his story.”

Robert Daniel Wagoner was born on July 13, 1932, in the rural village of Springfield, W.Va., which had a population of about 150. He was the youngest of 10 children born to Elwood Wagoner, a sawmiller and farmer, and Grace (Runion) Wagoner, who ran the household. The family churned its own butter and made cheese, slaughtered its own hogs to make sausages, and turned the leftover lard into soap.

As a child, Mr. Wagoner sometimes danced at ice cream socials held at the schoolhouse while one of his sisters accompanied him on piano. “There was a little stage with a curtain that opened, which thrilled me,” he told The Times in 1981. “I was very popular.”

Heeding his family’s wishes, he enrolled in the pharmacy program at West Virginia University in Morgantown. But his interest in dance remained. After watching a performance by the college’s dance society, Orchesis, he joined the group and began taking dance classes.

He graduated in 1954 and joined the Army as a second lieutenant in the medical corps, spending two years stationed at Fort Meade in Maryland and at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington. In the capital, he began studying dance with Ethel Butler, who had been a member of Graham’s company. She told him he needed to go to New York.

In 1956, Mr. Wagoner won a scholarship to attend the American Dance Festival in New London, Conn. While there, he worked with the modern-dance innovators Doris Humphrey and José Limón, as well as Graham herself, who at first found fault with some of his technique but told him, “You’ll do.” Moving to New York, he worked part time as a pharmacist while taking classes at the Graham studio. Before long, she invited him to join her company.

While in the Graham troupe, Mr. Wagoner originated roles in “Clytemnestra,” “Acrobats of God” and “Episodes,” among other works. With the Taylor company, he was in the original cast of “Scudorama,” “Orbs” and “Aureole,” a now-classic work that retains a portrait of his character in its happy hopping.

Much of Mr. Wagoner’s choreography was inspired by or used the words of his companion the poet George Montgomery. They lived together in a New York City loft filled with Mr. Wagoner’s collection of American folk art and antiques.

From 1989 to 1991, he served as artistic director of the London Contemporary Dance Theater. By the time he returned to New York, financial support for dance, especially in the form of government grants, had started to shrink, and he became focused on taking care of Mr. Montgomery; he died of Huntington’s disease in 1997. Mr. Wagoner closed his studio in 1992 and disbanded his company in 1994.

He became a sought-after teacher — first at the University of California, Los Angeles; next at Connecticut College in New London, from 1995 to 2005; and then at Florida State University, from 2005 to 2015. “I do believe that if we could all align our pelvises, wars would stop and everything would take its right place,” he told Dance Magazine in 2007. “The more dancers we have, the more healing can take place.”

In addition to Ms. Sincell, who lives in Oakland, the far-western Maryland town where Mr. Wagoner died, he is survived by his brother Loy and another sister, Martha McLaughlin. Mr. Wagoner bought a house in Romney, W.Va., in 1978 and had continued to spend part of his time there.

“Dancing is very, very difficult,” he told The Times in 1981. “When I am teaching or working with other dancers I try to encourage them to participate in the feeling of going to good places. I find that beautiful alignment and shifts of weight with nice pliant muscles that don’t grab or jam for movement all give me that feeling my family had of comfort, assurance and generosity.”