Category: Theater

Lincoln Center Theater Names Lear deBessonet, Bartlett Sher To Top Roles

[ad_1]

In a major development in the leadership of New York City’s non-profit theater scene, Lincoln Center Theater has named directors Lear deBessonet and Bartlett Sher to the roles of Artistic Director and Executive Producer, respectively.

The appointments take effect when longtime LCT artistic director André Bishop concludes his 33-year tenure this June, as previously announced. The transition comes in conjunction with the close of Lincoln Center Theater’s 40th anniversary season.

“It is the deepest honor of my professional life to serve as the next Artistic Director of Lincoln Center Theater, following the astonishing legacy of André Bishop,” said deBessonet, whose current tenure as Artistic Director of Encores! at New York City Center has included well-received productions of Once Upon a Mattress (currently on Broadway), Into the Woods, Oliver!, Jelly’s Last Jam and Titanic.

“I believe the theater is a space for the creation and restoration of community – and it is my intention in this job is to be of service to the mission and boundless possibilities of LCT, to our city, and to the field,” deBessonet’s statement continued. “I am thrilled to work alongside my dear friend Bartlett Sher, whose artistry and vision have profoundly affected my work as a director, and the extraordinary board and staff of Lincoln Center Theater to lead this theater into its next chapter of great success.”

Sher, a director whose credits include Aaron Sorkin’s hugely successful adaptation of To Kill A Mockingbird as well as productions of My Fair Lady, the 2017 Tony-winning Best Play Oslo, Fiddler on the Roof, The King and I and The Bridges of Madison County, called Lincoln Center Theater “one of the most important theaters in America” and touted Bishop’s legacy “of exceptional quality and enormous strength.”

“Lear deBessonet is an incredible artist and leader and I am deeply honored to collaborate with her as she guides Lincoln Center Theater into a transformative future,” continued Sher, whose position of Executive Producer is a new one for LCT. He has been a resident director at Lincoln Center Theater since 2008, and directs LCT’s current production of McNeal, a new play by Ayad Akhtar starring Robert Downey Jr.

In announcing the new appointments, LCT board chair Kewsong Lee said the hirings follow a comprehensive search of international scope, and thanked Bishop for his “artistry and leadership” of the institution. “LCT would not be where we are without him,” Lee said.

Said Bishop, “I am sad to be leaving, but incredibly grateful for the many happy years I spent at our wonderful theater. Lear and Bart are gifted and intelligent artists, and I am confident that Lincoln Center Theater will continue to grow and flourish.”

As Artistic Director, deBessonet will be responsible for all programming and season planning; cultivating and maintaining relationships with artists; and oversight and day to day operating of the staff and organization.

As Executive Producer, Sher will be responsible for the oversight of strategic priorities such as the development of international partnerships, brand expansion, as well as the expansion of fundraising and LCT’s resources.

Both deBessonet and Sher will assume their roles on July 1, 2025, and will report directly to the Chair of the LCT Board. Both will join the Board as ex-officio members.

[ad_2]

Source link

AMERICAN THEATRE | How To Tell If You’re a Theatre Kid

[ad_1]

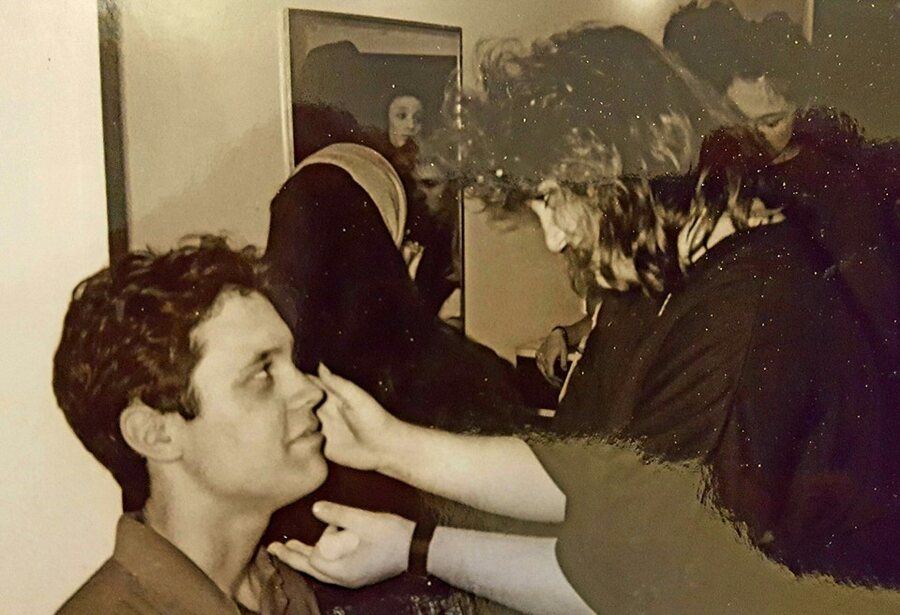

John DeVore and Becky Jollensten McGarity circa 1992.

Lights up on a small theatre in Brooklyn, New York. Enter John DeVore, late 40s. His hair and beard are streaked with gray. He stands in a spotlight centerstage and says:

My name is John, and I’m a theatre kid. I’m a theatre kid the way a raccoon is a raccoon, or a pineapple is a pineapple. I like to think of it as my astrological sign, something about me that is fixed. It is who I am, and I had little choice in the matter.

During one of my very first school plays, a teacher suggested I had been bitten by the acting bug, contracting a virus with no known cure. But I knew better: I had been screaming for attention since I was born. If I could have been the opposite of a theatre kid, I would have. But I can’t be who I’m not. I’m pretty sure the opposite of a theatre kid is a Dallas Cowboys fan.

Being a theatre kid is like that Groucho joke about not wanting to join a club that would have you as a member. That’s my experience, at least. I’ve never been a joiner. If I could change that about me, I would. I want to be loved and left alone at the same time. That is my default setting. My therapist is always telling me to open my heart to other people, and my usual response to his gentle requests is, “I’m trying, Gary.”

I once denied being a theatre kid, a bit like how the apostle Peter repeatedly lied when asked by the mob if he knew Jesus. My denial happened years ago, in the late aughts. 2008? Right before the economy cratered. Those were dark times for me. I had gone on an impromptu weeknight bender with a former colleague—a lonely old journalist with a talent for sniffing out bullshit and a sickening thirst for crème de menthe—who suspected I had acted in high school or college. I just laughed him off. Me? A theatre kid? No.

And my ruse would have worked had we not stumbled, piss-drunk, into a nearly empty karaoke bar and had I not insisted on performing a sloppy, surprisingly poignant rendition of the popular torch song “On My Own” from the blockbuster 1987 Broadway mega-musical Les Misérables—which, if you’re not aware, is a weepy, blood-and-thunder pop opera written by Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boublil and based on Victor Hugo’s 19th-century novel about poor French vagrants suffering beautifully. “On My Own” is sung by the forlorn street waif Eponine, who pines after handsome revolutionary Marius, whose heart in turn belongs to Cosette, the adopted daughter of our hero, ex-convict Jean Valjean. Eponine is a lonely victim of unrequited love, and later she dies in Marius’s arms, fulfilling the deepest, darkest, most pathetic fantasy of anyone who has ever longed for someone they could never have.

My former colleague could see the truth in my tear-filled eyes as I sang with everything I had. I couldn’t help myself. I was feeling it. I sang like I was competing for a Tony Award. I did that thing Broadway divas do where they slowly push one jazz hand toward the heavens as the emotions swell. I was in church, and from the back pew, I could hear him laughing and pointing at me like I was a fool. He knew a theatre kid when he saw one.

Like I said: dark times.

How can you tell if someone you know, or even love, is a theatre kid? Ask yourself this: Do they take a lot of selfies? Do. They. Enunciate. Every. Word? Do they frequently sigh heavily? Do they talk about themselves and their manifold feelings incessantly? These are just a few of the signs. Do they spell it t-h-e-a-t-r-e instead of t-h-e-a-t-e-r? That’s a good one. Only a true theatre kid spells it “theatre.” A “theater” is where you watch “theatre.” You see? No? This difference matters, and if you don’t think it does, you’re probably not a theatre kid, which may come as a relief to many of you.

Now, I need you to know that I know that t-h-e-a-t-r-e is just the British spelling of the word. But I much prefer the other explanation, don’t you? It’s more romantic. The theatre is an ancient art, a sacred, almost holy occupation. It’s a way to teach moral lessons and to celebrate the human condition; it is a story full of sound and fury that can levitate you or knock you sideways. The theatre is a spirit—and the theater is where you sit and cough politely, and then the curtain rises. There might not even be a curtain. A theater can be a space, any space. A storefront, an apartment living room, a parking lot.

This wisdom has been passed down from theatre kid to theatre kid from time immemorial. It was a veteran of my high school’s drama program who taught me the difference between theatre and theater. She was a full year older than me, but she knew things. I thought she was brilliant. I remember listening to her intently: Theatre was life. This lesson probably happened over cups of creamy, sugary coffee and plates of baklava at the local 24-hour diner, where all the theatre kids at my high school would go to celebrate after a successful production—a one-act or the spring musical.

We’d pour into the diner like an army of frogs, laughing and talking a mile a minute and singing show tunes, and the poor servers endured our overbearing youthful cheerfulness. My true theatre education happened either at that diner or backstage, during rehearsal breaks, and these impromptu lectures are the closest thing to an oral tradition in action I’ve ever encountered.

These 16-year-old elders patiently explained the superstitions and rules of the theatre, and I did the same when it was my turn to pass on the lore. I remember the rules like commandments: Never whistle backstage or say the name of Shakespeare’s famous tragedy about that Scottish couple who make a series of poorly thought-out career decisions. Both of those things are bad luck.

Saying “good luck” is also bad luck. You’re supposed to say “break a leg.”

There are all sorts of explanations as to what that phrase means. I was told, over a plate of french fries, that in ye olden times, the mechanism that raised and lowered the curtains was called a leg, and so to break a leg would mean that the audience cheered for so many encores, the curtain went up and down and up and down until it broke. Is that true? I have no idea. That’s just how I heard it.

Here are a few more sacred rules: Give flowers after a performance, not before. Always open the stage door for one of your fellow castmates and invite them to enter first with a graceful bow. One of my favorites warns against putting your shoes on any table backstage. Don’t do that. Why? I don’t think you want to find out.

There were also practical, straightforward rules about rehearsal and being part of a production. Always be on time. (“If you’re 10 minutes early, you’re on time. If you’re on time, you’re late.” That was the mantra. I was told to repeat it and to repeat it.) Don’t skip rehearsal. Memorize your lines. Stretch before every performance, and drink nothing but hot water with lemon juice and honey if you catch a cold. And never, ever become romantically involved with someone in the cast—a rule that was broken during every production at my high school, sometimes multiple times. Show romances were a huge no-no. This rule was meant to keep rehearsals drama-free. But rehearsals are intense and intimate, and it’s almost impossible to keep theatre kids from trying to make out with other theatre kids.

Show romances—also known as “showmances”—were looked down on, even by those who had them. The only exceptions were hookups between cast and crew, which worked in my favor. I will always be a sucker for a girl who can use power tools, because I cannot use power tools, and I fell for stage managers and set builders. A boy never hit on me, but I was ready for it, just in case, and had practiced a flattered, “I like you, but I don’t like-like you” speech in the mirror. I never got to perform that speech, which disappointed me. A few years later, in college, a beautiful man kissed me on the dance floor of a party. It was a deep and playful kiss, and before I could stammer, “I like you, but I don’t…,” he had disappeared into the crowd, and now that I think about it, that was disappointing too.

When I was a senior I gave the newbies at the diner a variation of the speech I was given in ninth grade. It went something like: “Look around at this table. These are the friends you’ll have for the rest of your life.” That wasn’t true, but in the moment it felt true, and that’s good enough. I also passed along to them what was passed to me, from senior to frosh, and that is to always, always attend the closing night cast party, and to stay until the very end.

John is an award-winning writer and editor who lives in Brooklyn with his wife and one-eyed mutt, Morley. His debut memoir, Theatre Kids, was published by Applause Books and came out this summer.

[ad_2]

Source link

A Docu-Play About Hamas’s October 7 Terror Attack

October 7, a verbatim play along the lines of The Laramie Project and Anna Deavere Smith’s works, is drawn from interviews with more than 20 survivors of the atrocities by Irish journalists Phelim McAleer and Ann McElhinney. – Los Angeles Times (MSN)

[ad_2]

Source link

A top US playwright has donated £1m to save Shakespeare’s daughter’s crumbling house

[ad_1]

Best known for his ’80s comedy ‘Lend Me a Tenor’ and his ’90s musical ‘Crazy for You’, the US playwright Ken Ludwig has clearly invested prudently over the years. Upon a recent visit to Stratford-upon-Avon he was told of the plight of the former home – to be fair, very former home – of Shakespeare’s daughter Susannah and her husband John Hall.

Built in 1613, Hall’s Croft (as the home is know) is one of the last complete examples of Jacobean architecture in the country. But to paraphrase Susannah’s dad, time doth waste it, and the 411-year-old building is in a fairly bad way at the moment, with steel girders installed to support the roof now sinking into the ground and an extension added later in the seventeenth century now pulling away from the original house, meaning it’s literally pulling in two directions.

However, as reported by the Guardian, when Ludwig was in town and told about this he didn’t hesitate to open his chequebook to the tune of a cool mil, the largest donation ever made to the Shakespeare’s Birthplace Trust in its 177-year history.

Lena Cowen Orlin, SBT’s vice-chair, said to the Guardian: ‘Hall’s Croft is a beautiful and atmospheric building that has been suffering from the need for serious intervention. Now we have the angel to make this possible … It’s a sleeping beauty of a building and Ken Ludwig is helping the trust bring it back to life as Shakespeare and his family knew it.’

Hall’s Croft has not been widely open to the public since the pandemic, which has given conservationists time to examine the building, but presumably Ludwig’s large donation ought to help the process of its eventual reopening.

For more information on Hall’s Croft, head to its official website.

Our complete guide to Shakespeare plays in London.

The best new London theatre shows to book for in 2024 and 2025.

[ad_2]

Source link

This Fall On Broadway: Bring On The Divas

Theater stages are the diva’s holy playground, where complex characters and powerful performances ask audiences to question their received ideas. A new slate of shows this fall promises both rapture and reexamination. – Washington Post

[ad_2]

Source link

The State of the Netflix Standup Special

[ad_1]

It can be hard to tell, these days, what some people mean by “comedy.” By the evidence of the work that comedians are doing, jokes may have dropped out of the definition. Like other performers in our Balkanized, make-your-own-prime-time-entertainment landscape, many comedians act less like artists or court jesters than like notionally humorous leaders of affinity groups or of minor, mostly harmless cults. They tend to say just what their viewers want to hear, but with the rhythm, if not the cathartic finality, of a joke.

This rather new phenomenon has to do with the fact that comedians are springing up from more corners of our media purview than ever. Increasingly, you don’t first become aware of them as comedians. One might be a podcaster you like, or make Instagram posts that show up on your “explore” page. Maybe another is a scene-stealing guest star on one of your favorite shows. Only later do you realize that they also happen to have a special on the way. There’s no Johnny Carson to introduce us to comics qua comics. They’ve got to sneak into your field of attention, often by way of some algorithmic back door, in order to grasp your affection.

Take Joe Rogan, for instance. He’s come to prominence—and to infamy—by way of his podcast, “The Joe Rogan Experience,” a hotbed of dorm-room conversation that sometimes plays as a mildly endearing bull session but just as often takes a turn toward conspiracy thinking and florid misinformation, with a formlessly reactionary bent. Rogan is a longtime standup, but it’s hard to find somebody who knew him first for his jokes. He was a bit ahead of the curve in at least one way: he built a career by other means. For decades, he’s been a fixture as a commentator of U.F.C.’s mixed-martial-arts matches. Well before he started his podcast, he was the host of an equally enriching program, “Fear Factor.” You know, the one where desperate Americans do nasty shit—eat a spider, suck a goat’s udder or a leech—for a little bit of cash.

In his new Netflix special, “Burn the Boats,” Rogan tells a story about a “Fear Factor” challenge that was so much more deranged than usual (the highest bar!) that the network, NBC, decided not to air it. It involved donkeys and their . . . reproductive emissions. I’m sorry to report that bit of news, but Rogan is not. He luxuriates in the scenario, rhapsodizing about the stuff—buckets of it—not for any revelation but to milk his crowd for gross-out reactions, not laughs but groans. In the special—which aired live in early August, an experiment that Netflix started with Chris Rock’s successful post-slap routine, “Selective Outrage”—Rogan wears jeans and an untucked mustard-yellow button-up shirt: business casual for guys who work for themselves. He shouts a lot, his way of creating emphasis when the logical gist of a joke won’t do the trick.

He starts the special—shot at the Majestic Theatre in San Antonio and directed by Anthony Giordano—with some local patter about Texas, where he now lives. He’s moved his podcast operation there, and has opened a club, called Comedy Mothership, in Austin. Sounding annoyed, he notes that some media outlets have called it an “anti-woke” comedy club. “You mean . . . a comedy club?” he says, with an exasperated tone. It’s a clunky bit of group-reinforcing business, aimed directly at the erogenous zones of his fans. It’s not us who share some special ideology, he seems to be saying. We just like to laugh. Everybody used to be like this! It’s them—our detractors—who are weirdly fixated.

Indeed, a large part of Rogan’s ethos is this kind of misdirection about what constitutes an unthinking group. The sort of trans joke he tells is quite old now. Forget about being offensive—whatever happened to trying not to be a hack? This one is about the way that like-minded lemmings come together and create a latticework of ideas:

Rogan is very worried about pregnant men. I guess he thinks they’re “funny,” but he also, with his shouted incredulity, wants you to think, like he does, that the mere idea of them is a universally applicable symbol of sociopolitical mania. He’s got a joke about bathrooms, too. Heard that one? In this case, anyway, the joke is about how a complex understanding of gender and the self is incompatible, somehow, with the tenets of social democracy. If you disagree, you’re a dope, an unthinking weenie, and with your scolding you’re making life less fun for Rogan and his followers. Sorry, I mean fans. This is the function of Rogan’s type of work: to reverse reality, to make members of a faction feel like freethinkers. There’s a living in it.

Disoriented by my encounter with Rogan, I went looking for other specials, hopeful that they’d revive my enthusiasm for a form of entertainment that I go to for surprises, not for assurances of my own correctness. Matt Rife is a twenty-eight-year-old comic who was delivered to me by the inscrutable whims of Instagram. He started standup comedy at fifteen years old, and worked at small clubs for years. He’s known for clips he shares online of his crowd work—improvising by giving audience members a hard time—and for the increasingly combative stance he’s taken against “snowflakes.”

You wouldn’t know that last bit from watching his latest Netflix special, “Lucid,” directed by Erik Griffin. All we see is Rife’s interaction with an audience of modest size, loosely organized around the theme of dreams. He asks soft questions about people’s aspirations. “What’s your dream that came true?” he inquires moonily. Rife has a dudey energy and looks like a member of a forgotten boy band—he often seems to be flirting, his way of showing that he’s interested in people’s stories. He’s not really trying to crack you up. Either you’re with him already—I wasn’t—or you’ll struggle to figure out the point of his act.

Speaking of dreams, the comedian Langston Kerman—you may have seen him on HBO’s “Insecure,” or on the brilliant satire “South Side,” for which he was a writer as well as a performer—once wanted to be a poet. In his exciting new Netflix special, a saving grace, called “Bad Poetry,” directed by the comedian John Mulaney, he talks about how he lost that aspiration. “I was gonna write silky metaphors,” he says mournfully. But he made the mistake of sharing his fledgling work with some high-school kids he taught. One girl shot his poetry down, and the dream wasn’t just deferred—it was dead.

What’s interesting about Kerman is that he isn’t a persona. All we really learn about him from the special is that he’s married, that he and his wife are both biracial—the “same mix,” he says: white dad, Black mom—and that they recently had a child. You’ll earn his enmity if you don’t coo over the photos he shares. But he’s not out to build a set of tenets or attitudes to which you can hitch your wagon. His style of comedy refreshingly repels that kind of watching. He’s all about jokes that start out absurd and get crazier as they proceed. The bit about mean schoolkids ends up being a way to justify a story about a teacher who fed a puppy to a snapping turtle in front of his class. Kerman once saw Forest Whitaker try to use the bathroom at IHOP—the “International House,” he says grandly—without being a customer. No dice. He imagines an uptight race man, perhaps a member of the Nation of Islam, who makes an exception for Kerman’s white dad. The stuff’s just zany. Remember fun?

We think of this kind of comedy—zing, zing, zing, with little breath between—as old-fashioned, something we left back on the Catskills circuit, where it belongs. But, in an age where so many people on our screens have some irritating point to prove, maybe work like Kerman’s is the way back to comedy on its own terms, as an art to be enjoyed in its purest form. Get up there and tell some jokes. I don’t want to join a club. ♦

[ad_2]

Source link

PCS Theater to kick off 113th season with ‘The Drowsy Chaperone’ – The Delaware County Daily Times

[ad_1]

PCS Theater to kick off 113th season with ‘The Drowsy Chaperone’ The Delaware County Daily Times

[ad_2]

Source link