Category: Theater

The Problem With Using Software To Determine What Shakespeare Did And Didn’t Write

Scholar Darren Freebury-Jones used a text database called Collocations and N-grams to spot parallel phrases and passages in Shakespeare’s plays and those of his contemporaries. Oxford Shakespeare scholar Emma Smith writes that Freebury-Jones’s computerized approach is less compelling than his own literary analysis. – The Telegraph (UK) (MSN)

[ad_2]

Source link

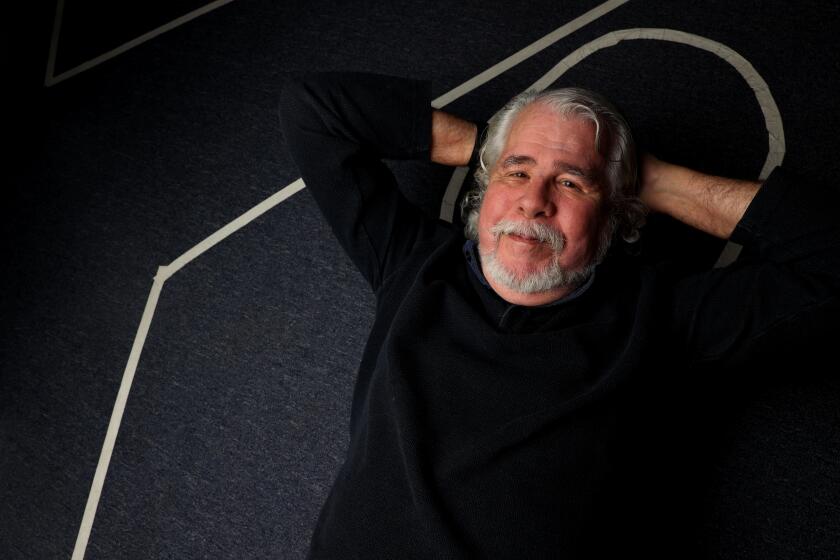

John Perrin Flynn on leaving Rogue Machine and the challenges of small L.A. theater

[ad_1]

"Part and parcel of running a theater in Los Angeles is waking up two to four times a year and not knowing if you're going to be in business the next week," John Perrin Flynn reflected after announcing his retirement as producing artistic director of Rogue Machine Theatre.

Speaking at a desk on the set of "A Good Guy," a new play by David Rambo that marks Flynn's last directorial project in his current leadership role at the theater, he was addressing the state of the field, widely seen to be in a state of crisis since the pandemic. Despite that struggle, the company he co-founded in 2008 is one of the few in town that has been flourishing artistically since venues reopened.

Financially, Rogue Machine continues to operate by the skin of its teeth, but the cavalry has come in the form of a game-changing grant from the Perenchio Foundation and an anonymous philanthropic gift that will further shore up institutional stability. The theater isn’t out of the woods — theater is never out of the woods in Los Angeles — but it has been given an opportunity to build on its growing reputation and consolidate its gains.

So why then has Flynn decided to leave at the end of this season, his 16th? First and foremost, he knows the company is in excellent hands with artistic director Guillermo Cienfuegos, a prodigiously gifted director who has been part of the theater's leadership team since 2018 and has been officially named Flynn's successor. (Cienfuegos is the pseudonym actor Alex Fernandez has adopted as a stage director.)

Co-artistic director Elina de Santos, who spearheaded the theater's playwriting programs for at-risk youth, is expected to continue. Justin Okin, another key leader, is taking over as full-time executive director. Flynn used to handle both the artistic and managerial sides of the job, an exhausting balancing act that perhaps explains his readiness to yield the reins.

“I'm 77, and the job is really thankless and difficult,” Flynn said with his usual unfiltered candor. “I was for 16 years working 60 to 80 hours a week, probably for no pay. I was not taking a salary. Once in a while, I would take a salary to direct or, when we did the musical “Come Get Maggie," I took a salary to produce the show because that was somebody else’s project. They were more or less just hiring us. But it’s tiring always scraping by. It’s probably not as bad for theaters that have patrons with deep pockets. But for years we never had a patron on that scale. Sometimes it was my money that allowed us to continue, sometimes it was a friend’s. But the constant worry is debilitating.”

Flynn, who had a long career in television as a producer and a director before starting Rogue Machine, wanted to return to his theatrical roots. “I had finished a Lifetime series that I'd worked six years on,” he said. “There's a lot to be said about that kind of employment. You make a lot of money and a lot of friends, but I was tired of it, and I wanted to go back to the theater."

In 2007, he directed the Southern California premiere of Craig Lucas' “Small Tragedy” at the Odyssey Theatre. The production was well received and he was eager to do more. He already had something in mind. On a whim, Flynn had answered an ad placed in a trade publication by an L.A.-based playwright who was looking for a director for his new script.

“I thought this was a silly waste of my time, but for some reason I was compelled to do it," he said. "The play was 'Lost and Found' by John Pollono, and after I read it in one sitting I picked up the phone and said, ‘I’d love to direct your play. You’re an exciting young talent.’ And so we did that play as a rental at a venue on Santa Monica Boulevard.”

A formative collaborative relationship was born. Flynn, however, was dismayed to discover that theaters were reluctant to produce new work by unknown writers. One producer who wanted Flynn to direct at his theater told him, "Oh, I can’t do new plays. No one comes. I lose my shirt.” Flynn said he “got pretty much the same answer” everywhere.

Rogue Machine was born precisely out of this need to present daring new work that wasn’t finding a home elsewhere in the city. The vacuum left by the nonprofit behemoths, who in Flynn’s view have largely abdicated their responsibility, created an opportunity, a place to showcase the works of such intrepid writers as Samuel D. Hunter (“A Bright New Boise” and “Pocatello,” among others), Christopher Shinn (“Dying City”), David Harrower (“Blackbird”) and Enda Walsh (“The New Electric Ballroom,” “Penelope”).

No one has a better claim of being Rogue Machine’s house playwright than Pollono. His play “Small Engine Repair” helped put the company on the map. A long-running hit at Rogue Machine, the play was subsequently produced off-Broadway, where Charles Isherwood in his New York Times critic’s pick review compared Pollono to Martin McDonagh.

“I’m surprised Mr. Pollono hasn’t already been snapped up by the hungry maw of television,” Isherwood presciently remarked in an aside. More than a decade later, two of Pollono’s plays that had their start at Rogue Machine, “Small Engine Repair” and “Razorback” have been adapted to the screen. (“Riff Raff," based on "Razorback,” premiered this fall at the Toronto Film Festival with a cast that includes Jennifer Coolidge, Gabrielle Union, Pete Davidson, Ed Harris and Bill Murray.)

Flynn himself marvels that a small L.A. theater with a shoestring budget could help launch a major career. He points to Kemp Powers’ “One Night in Miami…" as another instance of Rogue Machine being the little engine that could. The play, a fictional take on the night Muhammad Ali, Malcolm X, Sam Cooke and Jim Brown gathered in a hotel room in 1964 and exchanged heated views on the Civil Rights struggles, premiered at Rogue Machine before enjoying a successful run at London’s Donmar Warehouse. A widely praised film version, directed by Regina King, was released in 2020.

Rogue Machine plays come in several varieties. Flynn is open to the Beckettian experimentation of Walsh's “The New Electric Ballroom," a play he decided to produce after seeing an international company perform the work at UCLA Live and believing that he could offer Los Angeles audiences a different way inside the drama. A play like Harrower’s “Blackbird,” too morally disquieting to be produced by the city's risk-averse big-budget theaters, appealed to Flynn’s heterodox side. Hunter's spiritually searching plays offering acute portraits of red state America appealed to Flynn's metaphysical and sociopolitical sides.

The absence of women playwrights in this summary mirrors the absence of women playwrights on the list of favorite productions Flynn included in his retirement letter to the company. Rogue Machine has taken strides to diversify its programming, but a persistent gender gap in playwriting signals a problem that will have to be redressed by Cienfuegos and his team.

Developing L.A. voices, Pollono and Powers among them, has been integral to the theater's mission. Rogue Machine has provided a nourishing community to playwrights through workshops, salons and educational outreach. Flynn said that his mandate all along has been to produce world premieres along with plays that are new to Los Angeles.

Occasionally, Rogue Machine has produced some clunkers, head-scratchers like the musical “Come Get Maggie” or plays that just weren't ready for prime time. Are these occasional flops simply the cost of doing new work?

Flynn admitted that there are many factors at work. Sometimes there are personal relationships involved and sometimes there are financial incentives that allow the theater to produce at a time that it would otherwise be dark. But it's always a disappointment, he said, when the art doesn't come together.

When you’re worried about making the rent — and Rogue Machine has moved around a lot — you're not always going to live up to your ideals. After establishing its reputation at Theatre Theater, the shape-shifting venue on Pico Boulevard with a flexible black box that housed some of the company’s most memorable offerings, Rogue Machine moved to the MET Theatre on Oxford Avenue before heading out to the Electric Lodge in Venice.

In 2021, Rogue Machine moved to its current home at the Matrix Theatre on Melrose Avenue. Cameron Watson’s pitch-perfect 2022 production of Daf James’ “On the Other Hand, We’re Happy” inaugurated what has been one of the brightest periods in the company's history. Last year’s L.A. premiere of Will Arbery’s “Heroes of the Fourth Turning,” sensationally directed by Cienfuegos, was one of the best things I've seen anywhere since theaters reopened.

Were it not for Flynn's leadership, L.A. theatergoers would have been deprived of local introductions to some of the most innovative talents in contemporary playwriting. While the Mark Taper Forum, Pasadena Playhouse and the Geffen Playhouse fretted about the taste of their least adventurous subscribers, Rogue Machine reminded us that theater is most alive when misbehaving.

“Los Angeles played an important part of the regional theater movement in America,” he said. “But there’s been a calcification of the larger theaters. They are afraid to do important work. Before the pandemic, Center Theatre Group, which was already in trouble, spent more than $40 million on a season that included a number of touring productions. Our culture is stuck in these old habits of thinking. I have a horse in the race, but imagine if that $40 million went to eight smaller theaters. Imagine the kind of artistic boost that could happen.”

One lesson that Flynn draws is knowing when it’s time to get off stage. “[Center Theatre Group founder] Gordon Davidson stayed at the party about five years longer than he should have," Flynn said. "And the Taper has never recovered. There was a time when Gordon could have had Oskar Eustis take over. Oskar was here. Oskar was his protege. What would that have meant to Los Angeles?”

Eustis made history of his own at New York’s Public Theater, where “Hamilton” emerged under his watch. But Los Angeles theater is poised for a renaissance, with Danny Feldman at Pasadena Playhouse, Snehal Desai at CTG and Tarell Alvin McCraney at the Geffen Playhouse all determined to turn the page on a lackluster last decade, characterized by unfulfilled potential, dwindling audiences and watered-down missions.

Flynn acknowledged that we're in a precarious period of transition. Precarious not just because of the budgetary realities but also because of the need for structural and audience renewal. The old models aren't going to save us. Each generation, he believes, must find its own way to reestablish the art form's institutional vitality.

When asked which theaters Flynn sees as peer organizations, he doesn’t trot out communal news releases but answers succinctly: Echo Theater Company. Both theaters, he said, are looking for "the kind of work that needs to be put before the public so the public can experience it and question whatever the play is bringing up."

Flynn often compares notes with Echo Theater Company artistic director Chris Fields who similarly struggles to get the rights to plays that agents are reluctant to bestow on small L.A. theater companies, no matter how superior they may be to their larger counterparts. There's agony on Flynn's face when he talks about plays by McDonagh and Annie Baker that for one reason or another proved elusive.

“I'm always looking for a play that exposes the human condition,” he said. “Who are we? What are we doing here? How did we get here? Where are we going? The kinds of issues that reveal the complexity of life. The question of what is good, because good is not easy. It’s not black and white.”

Maybe one of the reasons playhouses of integrity are having such a difficult time is that we’re living in an era when schematic thinking has taken over. Social media has ingrained in the public a habit of ideological certainty that playwrights worth their salt know is a lie.

On offer now at Rogue Machine is the world premiere of Rambo’s “A Good Guy." The drama, which is being performed upstairs at the Matrix in the cozy hideaway of the Henry Murray Stage, examines the old right-wing saw that a good guy with a gun somehow makes us all safer. It’s an appropriate last play for Flynn to direct in his role as the leader of a theater committed to showing us our collective countenance, warts and all.

Flynn deserves a break from his heroic theatrical labors, but he’s not done yet. He'll continue to direct at the theater when the spirit and the playwright move him. And having restated his acting career, he's open to casting opportunities when he can serve the play. Cienfuegos promises to build on what is already an extraordinary legacy, making Rogue Machine the inclusive, intimate center of hard-hitting playwriting that L.A. deserves.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.

[ad_2]

Source link

The importance of being dangerous – what should and shouldn’t be aired on stage

[ad_1]

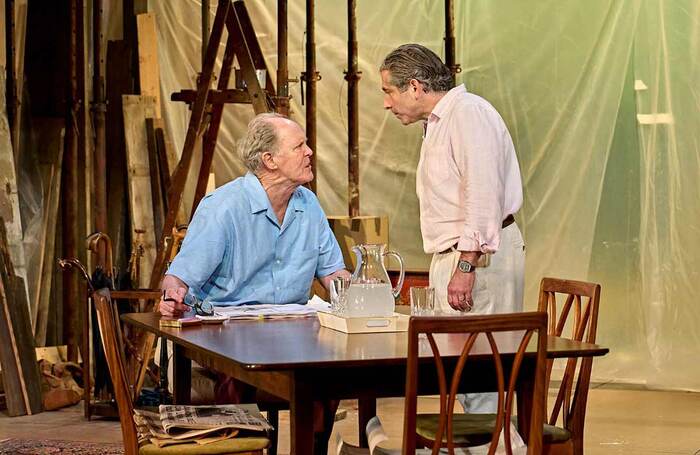

John Lithgow and Elliot Levey in Giant at the Royal Court, London. Photo: Manuel Harlan

Anyone remotely interested in current debates about what should and shouldn’t be said in theatre must see Nicholas Hytner’s production of Giant, says David Benedict

Support The Stage by registering or subscribing

To continue reading this article you must be logged in.

Register or login below to unlock 3 free articles every month.

OR

Or subscribe today and get unlimited access to thestage.co.uk.

[ad_2]

Source link

How Does Lin-Manuel Miranda Decide What Projects To Pursue?

“If it’s just one idea, it will probably die in the impulse phase. If the idea opens avenues and you see many more roads, that’s worth pursuing. It doesn’t leave you alone.” – Fast Company

[ad_2]

Source link

‘You become addicted to pressure’: Rufus Norris on success, stress and the National Theatre’s survival | Rufus Norris

[ad_1]

When Rufus Norris was appointed the sixth director of the National Theatre in 2015, he was terrified by the prospect. “Why would I think I could do that?” he says. “I had run a fringe theatre 20 years ago [the Arts Threshold, from 1993 to 1995].” Yet, being terrified was exactly what led him there. “‘Step into your fears’ has been a mantra for my whole career. Go into the thing you’re afraid of because if you’re afraid of it then it means you won’t know what you’re doing – which means you’ll learn more.”

Norris, 59, is sitting in the building that has since become his home, reflecting on his near-decade at the National’s helm. The fear is soon to come full circle; six months from now, he will be back out in the big, bad, scary old world again. Directors have traditionally done two five-year terms – he was not asked to do a third. He is pleased with this outcome because “change is healthy in our industry – it’ll be really good to have a fresh blast come through”. The blast he refers to is Indhu Rubasingham, who floats around outside his office, midway through a year-long handover, and it is clear from the teasing repartee as they pass each other that there is warmth between them.

He might not have had extensive experience in running a building when Norris took over from Nicholas Hytner but he had a wide-ranging, eclectic CV: training as an actor at Rada before directing award-winning shows across the West End and beyond as well as several at the NT, working in opera, directing films that won acclaim in Europe, including at the Cannes film festival.

Known for his lack of grandness, Norris is reluctant to offer up high-minded pronouncements on his departure. “I’m still completely up to my eyes in doing the job and I will be until the day I walk out because that’s the nature of this place,” he says. To that effect, there is next season’s programme, announced on Tuesday, which is his final. While the timing for many of the shows on it has been accidental or serendipitous, what is deliberate is its range. Extending representation both on the stage and off has been a central feature of Norris’s tenure. Many have welcomed the diversity, with greater visibility around race, gender, disability, as well as the nurturing of new writers.

Some, though, have suggested that this is not what a national theatre is for. What would he say to them? “We’ve got Coriolanus on tonight. Would you like to come to see it?” he volleys back. His changes should not be mistaken for political acts, nor part of a culture war, he says. “We’re called a national theatre, which means we have to be nationwide and that we have to represent the nation. It’s very easy to look at the demography of the UK, those figures are available to everyone. Half the people in this country are women [for example], so let’s get to a place where that is the representation we are seeing on our stage in terms of actors but also writers and directors.”

While this statistical representation is important, what is key is that it actually makes the work better. “If you look at art across the board, the world over, bringing different voices in – different lived experience and truths – increases the quality of it.”

The same applies to heritage, he says. Norris grew up in Africa and Malaysia, while the current deputy artistic director, Clint Dyer, is Black British, born and bred in London. “Who’s British, me or Clint? I would say he’s more British than I am. Some people would disagree with that. I don’t agree with them.”

With these guiding principles in mind, how does he reflect back on the criticism he received for a mid-season announcement featuring no female writers in spring 2019? “The way we’d been thinking about it is that we need to get the representation across the year, and what that taught us was that we were going to be judged on every specific announcement, so you then bear that in mind.”

A high point for Norris has undoubtedly been in the New Work Department he set up. “The first thing we did was move the literary department from this [main] building up to the studio and encourage much more engagement with the projects coming through it.” Last year, the NT’s new plays [from Beth Steel’s Till the Stars Come Down to Gillian Slovo’s Grenfell, Jack Thorne’s The Motive and the Cue and James Graham’s hugely popular Dear England] came out of long years of process, all of them “slow-cooked” in this department. “Seeing them come to fruition in the same year was proof of the pudding in terms of that decision to strengthen our commitment to having the writer in the room, which has been a key priority for me.”

Does he acknowledge the historical bias that keeps some excluded from this developmental process, to which many writers of colour have attested? “I think one of the unavoidable truths about theatre culture is that historically the opportunities have not been broad enough. That’s something that a lot of people have been working hard to redress, including this place.”

Other “wins”, as he sees it, involve the theatre’s engagement with the nation, especially in collaborative regional projects such as We’re Here Because We’re Here, which he did with the artist Jeremy Deller in 2016, involving community members across the country marking the 100th anniversary of the first battle of the Somme. “It really broke out of what a National Theatre had done before and people’s expectations of what theatre could be.” There was the staging of Pericles by a company of all ages from across London, too, in 2018, the first project under the Public Acts initiative. He has also worked hard around sustainability and the environment within theatre and it is an area in which he would like to remain involved.

In terms of legacy, he does not think it his job to decide where the volume might be turned up or down after he leaves but he hopes the practice of having the writer in the room continues. This refers not only to new plays but revivals, adaptations and musicals so they feel fresh and evolved. For example, when Jamie Lloyd recently revived The Effect, its writer, Lucy Prebble, was there.

The theatre’s digital work has been immense in the past decade, he feels. “NT Live was created in Nick Hytner’s time – we just ran with that brilliant idea. And then out of Covid, NT at Home was formed and is now watched across 184 countries by people “who will never have the chance to come here”. There is the NT Collection, too, which is in 89% of state secondary schools, free of charge. “That reach is really profound.”

That’s not to say the Covid pandemic, when theatres turned dark across the land, was not a devastating time. In fact, it was the biggest crisis point of Norris’s tenure and he speaks of “before Covid” and “after Covid” in relation to the earthquake it brought for the industry.

He lobbied hard for government support and feels that Boris Johnson’s cabinet listened; the culture recovery fund helped to avert “the absolute worst”, he says, and he is thankful for it. Was there a moment when he thought the NT could sink? “I think it would be a very foolhardy government that allowed their national theatre to disappear, particularly when theatre is historically such an important part of this country’s culture. I didn’t think that, in the long-term, there wouldn’t be a national theatre, but I thought that in the short- to medium-term it could be changed beyond recognition. And I feared if there wasn’t quick action we would lose a huge proportion of a workforce that is highly skilled and has taken generations to build up. I also felt that the effect it would have on our freelance community would be devastating and in some ways it was.”

If there was any kind of silver lining to that time, it was in the way the industry banded together. “It decimated audiences around the country, which have not fully recovered. But the crisis demanded that our relationship with each other across the sector, and from there our relationship with government, became more coherent … I think some of what we learned about how to talk to government has remained.”

David Hare recently criticised the NT for not putting on enough plays and spoke of his desire to see the resurrection of the repertory system on which the theatre was founded. Does Norris think this is a thing of the past now? “No, I think it’s great for audiences and there are lots of positives about it but also great challenges. With all due respect to David, he doesn’t have to deal with the pragmatics. I think it’s likely at some stage that the National will at least in part return to that. It just hasn’t been right for this time. When you’re talking about your survival, you make some big decisions and that was one of them.”

During Norris’s tenure, there have been six prime ministers and a revolving door of 11 culture ministers, some taking theatre more seriously than others. He has not met the current incumbent, Lisa Nandy, but “I like what I read about her, she seems very smart … I look forward to developing a relationship with her in the time we’ve got left”.

Post Covid challenges remain, especially in encouraging audiences back, but Norris does not worry about the future of theatre in the long-term. “It doesn’t matter how good television and film get, or how good your phone is. People still want to be together, and they want to be told stories.”

He would not presume to offer any advice on how to do the job to Rubasingham and Kate Varah, executive director and joint chief executive. “I would, to a degree, be teaching my grandmother to suck eggs. But I would advise her [Rubasingham] to keep healthy. The job is very demanding. It’s very easy to get dragged into 90 or 100-hour weeks. That needs a counterbalance.”

I wonder what his next move may be, six months from now. Will he direct, return to film, maybe even retire? Absolutely not to the latter, but at the moment he is deliberately trying to keep it completely open. “I’m going to have a year away from London. I want to switch off, be in nature. I want to try and recalibrate, get my creative energy back.”

He also wants to wean himself off what he thinks of as a dependency on the job “because you do become addicted to work and pressure and you know, ‘The world needs me so I must get out of bed really early or never go to bed at night.’ Of course the world doesn’t and that’s a recipe for disaster.”

Norris trained as a painter and decorator, working in the building trade for a few years before going to Rada. Might we see him coming back as a builder or a carpenter? “Funnily enough, I’m going to spend a week in the carpentry workshop [at the NT] as a mini apprentice. It’s on my bucket list and one of the things I’m going to do before I go.” There is also his love of wild swimming and kayaking. He opens up his notebook to reveal two beautifully pencil-sketched kayaks along the margins. “This is a doodle I did the other day. I’m designing the kayak that I want to have when I go away, to work out the best shape for it.”

His wife, Tanya Ronder, a writer with whom he has collaborated, most recently on the NT’s Christmas show, Hex, left the industry to retrain in 2019 (he does not want to say any more) and her move has inspired him to possibly do the same. “I’ve never been to university. Would that be a thing to do at some stage? I’m very keen to learn new things.”

Whatever he decides, it will be guided by his mantra: run towards the things that scare you. “The important thing is to not grasp at any kind of security,” he says. “Step into the fear.”

Spring season at the National

Suzie Miller’s new play, Inter Alia, following the success of her last, Prima Facie, will star Rosamund Pike

Shaan Sahota’s first play, The Estate, a family drama-cum-political satire, featuring Adeel Akhtar

David Lan’s The Land of the Living, about the displaced children of the second world war, directed by Stephen Daldry and starring Juliet Stevenson

The final instalment of David Eldridge’s trilogy, End, directed by Rachel O’Riordan

A staging of Michael Abbensetts’ Alternations, a seminal work about the Guyanese experience of 1970s London and the Windrush generation, from the Black Plays Archive based at the NT, starring Arinzé Kene and Cherrelle Skeete.

Stephen Sondheim’s final musical, Here We Are, which premiered off-Broadway in 2023, starring Rory Kinnear and Tracie Bennett

A return of two recent NT shows: James Graham’s football drama about Gareth Southgate’s team, Dear England, now with an updated ending, and the Aneurin Bevan play, Nye, starring Michael Sheen

[ad_2]

Source link

Scripts About Politics Lead List Of Most-Produced Plays In U.S.

For the second year running, Heidi Schreck’s What the Constitution Means to Me is the country’s most-produced play, and in fifth place is Selina Fillinger’s POTUS: Behind Every Great Dumbass Are Seven Women Trying to Keep Him Alive. – The New York Times

[ad_2]

Source link

How ‘Discoshow’ Spun Las Vegas Into Funkytown

[ad_1]

Revisiting 1970s New York, a new theatrical experience is one history lesson that’s all about the good times.

[ad_2]

Source link