Category: Theater

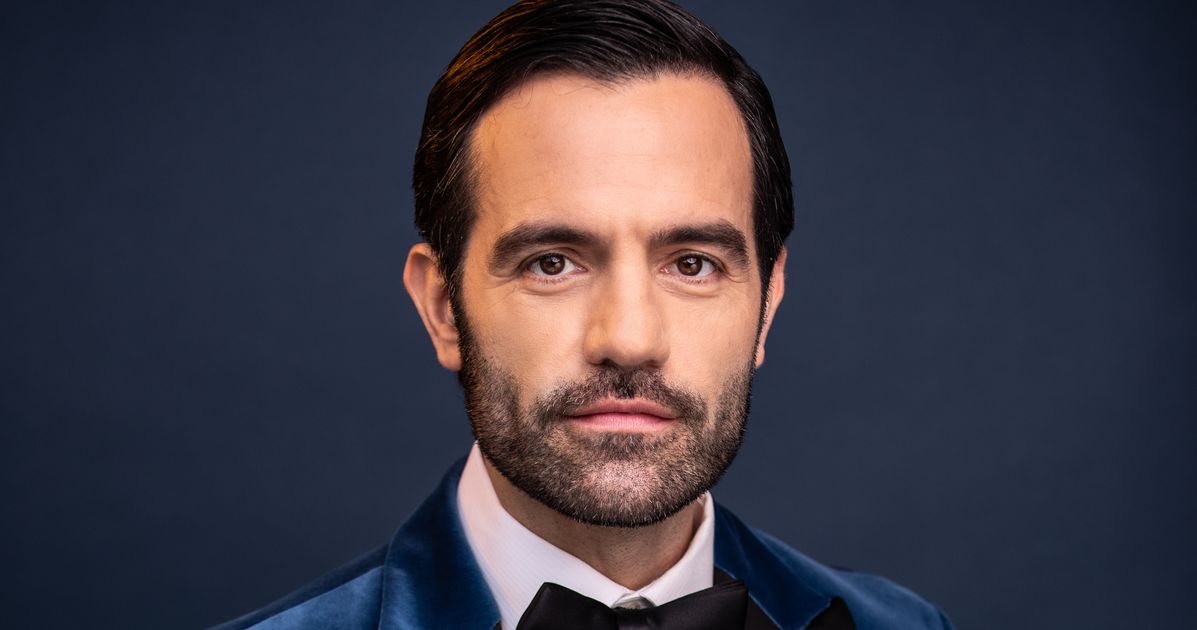

In ‘Little Shop Of Horrors,’ Conrad Ricamora Gets A Chance To Smash Theatrical Barriers

[ad_1]

Conrad Ricamora endeared himself to a generation of television viewers by charming the pants off Jack Falahee ― in both the literal and figurative sense ― on ABC’s “How to Get Away with Murder” for six seasons.

Many fans, however, may be surprised to know that Ricamora was a theater actor prior to his television fame, with a stage resume that includes the 2015 Broadway revival of “The King and I” as well as the off-Broadway musicals “Here Lies Love” and “Soft Power.”

This spring, Ricamora returns to the stage in the off-Broadway revival of “Little Shop of Horrors,” now playing at New York’s Westside Theatre. The musical follows a meek flower shop assistant named Seymour Krelborn (Ricamora), who discovers an extraterrestrial plant that feeds on human flesh. The plant becomes a national sensation and helps Seymour bond with a similarly down-on-her-luck colleague, Audrey (Tammy Blanchard), but catastrophe looms as he must figure out new ways to satiate his horticultural discovery’s thirst for blood.

When Ricamora joined the musical’s cast in January, he faced the unenviable task of embodying a role played by Jonathan Groff to great acclaim when the production opened in 2019. Groff’s successors in the role have also included actors Gideon Glick and Jeremy Jordan, both beloved Broadway stalwarts who have since parlayed their theatrical chops into success on television and in film.

Fortunately, Ricamora had not seen his predecessors’ performances as Seymour beforehand, which meant he was able to approach the role with neutrality. Like Groff and Glick, the California-born Filipino actor is gay. He is also the first Asian American to assume the role in the current production, and being to offer audiences that intersectional representation is something he doesn’t take for granted.

“Seymour isn’t a gay or Asian character, so it’s an opportunity for me to tell a story that isn’t a queer or Asian American story, but just a human story,” Ricamora told HuffPost. “I would love for other Asian American actors to have opportunities to do that. That’s something I’m really excited and hopeful for.”

“This is a character who was born into really desperate, desolate circumstances,” he added. “His story is about the lengths we, as human beings, will go to find connection and love, whether it’s right or wrong. That’s a strong theme in the show that I really love.”

Ricamora’s “Little Shop of Horrors” casting comes at a time when Asian American representation in New York’s theater industry remains at a startling low. A 2019 study conducted by the Asian American Performers Action Coalition found that while 33% of all roles on New York stages went to performers from marginalized groups in the 2016-2017 season, Asian actors filled just 7.3% of those roles.

That community was poised to get a boost in theatrical representation in 2020, when nine works by Asian playwrights were slated to be staged in the Big Apple. Before many of those works were produced, however, the COVID-19 pandemic shut down many theaters and performance venues across the United States.

Once Broadway and off-Broadway theaters reopened their doors last fall, many were eager to tout the theater industry’s so-called “reckoning” when it came to presenting Black and Latinx experiences onstage. When asked why he believes the Asian presence in theater has not yet followed suit, Ricamora said, “That’s a dissertation-level conversation that is multilayered and nuanced.”

“As Asians, we’re not always encouraged to use our bodies and physicality and image in terms of expression,” he said. “Within our own culture, there’s not a lot of encouragement in terms of showing our own image in front of people. We’re taught to work hard behind the scenes, to keep our heads down and achieve status and success that way. But with that comes a lack of physical image-based representation. That does a lot to our self-esteem and sense of selves.”

Ricamora is slated to star in “Little Shop of Horrors” through May 15, after which he’ll be replaced by “Pitch Perfect” and “Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist” star Skylar Astin as Seymour. About a month after that, he’ll return to the small screen alongside Joel Kim Booster, Margaret Cho and Bowen Yang in Hulu’s “Fire Island,” which has been billed as an LGBTQ-inclusive adaptation of “Pride and Prejudice” that takes place on Fire Island, New York’s premier gay resort destination.

“It was just a dream to work with everyone on that movie,” Ricamora said. “[Booster] has been coming to Fire Island for years, and one day, he was sitting on the beach watching all of these cliques of people socialize and interact. He realized those dynamics felt a lot like ‘Pride and Prejudice.’”

“I’m super excited to share it with the world,” he added.

Jeong Park/Searchlight Pictures

Ricamora also recently joined forces with actors Kelvin Moon Loh and Jeigh Madjus to develop “No Rice,” a television series based on their collective, real-life experiences.

“It’s about gay Asian best friends who are navigating their own identities while looking for love, sex and acceptance in New York City,” Ricamora said of the project. “We sold it a year ago and will hopefully get it greenlit soon.”

But as he plots his next Hollywood chapter, Ricamora said his “Little Shop of Horrors” experience has reminded him of why he’ll always return to live theater in some capacity.

“Theater gives you a sense of community that no other entertainment medium can provide,” he said. “You can’t get that from watching Netflix or going to a movie theater. Anything can happen on any night, and we get to experience that with the audience in real time. That’s something I took for granted previously but now am relishing so much.”

[ad_2]

Source link

Australian theatre companies are shunning Shakespeare. A much-needed break or a mistake?

[ad_1]

A decade ago, William Shakespeare was the most performed playwright in Australia. In 2024 not one mainstage theatre company in Australia will perform Shakespeare. The only exception will be Bell Shakespeare.

This shift has been a long time coming. Theatre-makers such as Lachlan Philpott, Nakkiah Lui and Andrew Bovell have been calling for less Shakespeare and more new work since the mid-2010s.

Today, their advocacy is bearing fruit.

Of the 79 plays being performed in 2024, 68 (87%) were written after 2000, 60 (76%) were written after 2014 and 23 (29%) will have their world premiere in 2024. Only three were written prior to the 20th century – and that’s if you count Kip Williams’ new adaptation of Dracula, alongside Bell Shakespeare’s two plays.

New work is important. A truly rich cultural conversation must include a variety of voices and fresh perspectives. But alongside new work and new voices, nuanced engagement with the past is needed.

A forum for conversations

Shakespeare is important, not just because he wrote great plays, and definitely not because he is perfect. He is important because we have, for 400 years, made him important, using his work to have rich conversations about identity, truth, meaning and morality.

These conversations are worth participating in.

Australia’s mainstage comprises 11 companies: State Theatre Company of South Australia in Adelaide; Queensland Theatre and La Boite Theatre in Brisbane; Melbourne Theatre Company and Malthouse Theatre in Melbourne; Black Swan State Theatre Company in Perth; and Belvoir, Bell Shakespeare, Griffin Theatre Company, Ensemble Theatre and Sydney Theatre Company in Sydney. All except La Boite have announced their 2024 seasons.

The fact that none of these companies will perform Shakespeare next year suggests a decline in engagement with the canon outside of adaptations.

This decline is, in some ways, justified. We don’t need to perform Shakespeare all the time. We certainly don’t need to trot out tired, uninspired performances just for the sake of doing Shakespeare.

But if new work is not in conversation with the canon, we risk taking an uncritical and oversimplified view of the past – and present and future. We risk understanding ourselves merely through the lens of now, rather than enriching our present through discussion with our history.

Playwrights Philpott and Bovell have expressed understandable frustration at productions tying themselves in knots trying to make Shakespeare “relevant”. If your aim is to make the text reflect modern values, why not simply perform a new play?

Perhaps we do need a break from Shakespeare if all we can do is insist he is always, and in all things, our contemporary.

Read: Australian Performing Arts Forum 2023: an overview and summary

Critical engagement with Shakespeare

There is an alternative to this false dilemma. We are not restricted to either using Shakespeare as a sock puppet to voice our own ideas, or ignoring him altogether. Rather, we can perform Shakespeare in a critically engaged, nuanced way.

This means avoiding easy categories like “problematic” or “universal”. Like any fruitful conversation, it means listening, sitting with discomfort, learning, recognising what still speaks to us, and responding to what doesn’t.

Conversing with Shakespeare does not mean smoothing over problems or forcing him to agree with us. Sydney Theatre Company’s 2022 production of The Tempest, directed by Kip Williams, attempted to correct the play’s racism by radically editing the text.

By trying to solve The Tempest, the production glossed over its problems rather than engaging critically with them.

There are excellent examples of Australian theatre makers grappling with problems in Shakespeare.

Anne-Louise Sarks’ 2017 production of The Merchant of Venice for Bell Shakespeare explored the uncomfortable religious and social dynamics of the play.

The scenes in which Shylock is forced to surrender both his property and his faith were jarringly and uncomfortably melancholic. There was no attempt to shrug off the pain of the play’s conclusion for Shylock and his daughter Jessica.

Jason Klarwein and Jimi Bani’s 2022 Othello at Queensland Theatre used translation, casting and design choices to confront and interrogate the themes of the play.

This production explored and highlighted racism and sexism, both in 20th century Australia and within the play itself.

Othello has a vexed performance history, and this production was an important contribution to a 400-year-old conversation.

In Benedict Andrews’ 2009 production of The War of the Roses for Sydney Theatre Company, Shakespeare’s Henry V was stripped back to a series of soliloquies spoken by Ewen Leslie.

Covered in glitter, then oil and eventually blood, Leslie as Henry V invited audiences to confront not only the humanity of “the warlike Harry”, but also the horror associated with his military triumph.

Talking back to history

By confronting – rather than avoiding, removing or “fixing” problems in Shakespeare – productions can invite audiences to ask important questions. Why have certain ideas been acceptable in the past? Why are they not so now? What are we doing differently today, and what should we be doing differently?

Nuanced, two-way conversations with our cultural history are vital to progress.

Decolonising the canon does not mean ignoring it, but dialoguing with it. It means learning from, questioning and talking back to our history. Doing this will allow us to better understand our present and know who we would like to be in our future.

Of the 79 works being performed on the 2024 Australian mainstage, 68 were written in the new millennium. Shifting the balance of old and new ever-so-slightly would enrich our cultural conversation.

Caitlin West, PhD Candidate in Drama and Theatre Studies, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

[ad_2]

Source link

Danny DeVito, His Daughter and a Lot of Baggage (Onstage)

[ad_1]

The first time Lucy DeVito acted onstage — an electrifying turn as an ant in a second-grade play about insects — her father, Danny DeVito, watched proudly from the back of the room. (DeVito, who had already starred in the television series “Taxi” and appeared in films like “Terms of Endearment” and “Throw Momma From the Train,” didn’t want to pose a distraction.)

Now, as Lucy makes her Broadway debut, he has the best seat in the house: right onstage with her. Starring together in Theresa Rebeck’s new comedy, “I Need That,” they are playing the roles they know best: father and daughter.

Directed by Moritz von Stuelpnagel, the play, in previews at the American Airlines Theater, centers on the widower Sam, a recluse and hoarder facing eviction. His daughter, Amelia, and his best friend, Foster (played by Ray Anthony Thomas), beg him to give up and give in — give up the stuff; give in to some help — much to his chagrin, over the show’s 90 minutes.

In Midtown Manhattan recently, the DeVitos sat in a rehearsal space, the detritus from a deli breakfast spread out on a table in front of them. The improvised set was a disaster, a small kitchen surrounded by piles of junk: board games, record players, plastic bins, garbage bags, clothing, shoe boxes. At one point in the show, Danny’s character unearths a television set from several layers of trash.

The script was still pliable, and both of them were grasping to achieve the fullness of their characters. Danny was memorizing his lines, looking up toward the heavens every time he drew a blank. (When he focused, he curled into himself, hunched into a hug, his bottom lip out in consternation.) His riffs bejeweled every line: When the script called on him to invite his daughter in for breakfast, he instead laid out a menu. “You want breakfast? Coffee? Cereal? Eggs? Fruit? I got a really ripe plum!”

Lucy, on the other hand, was more studious and probing. During her character’s apex in the show, the plea for her father to change his life, her voice curdled from sadness into a resigned anger. While running those lines, Lucy pulled over to ask for directions from von Stuelpnagel: Where is her character, emotionally, right now? Should she remain hard or retreat back into softness? They talked it through, Lucy smacking a tiny Rubik’s Cube into her palm to punctuate her points. Her father looked on, silent and smiling.

“She works a lot. She’s really, really in there — she’s in there, digging, and that’s part of the whole idea,” Danny said a few weeks later during a break from rehearsals. “She never lays down on it. She’s always on it.”

Danny, 78, began his acting career on the stage. Eager for something to do after graduating from high school in Summit, N.J., he began working at his sister Angie’s beauty shop. She encouraged him to train as a cosmetologist at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, and once he was immersed in the world of professional theater, he decided to try out acting for himself. After he graduated in 1966, DeVito acted in productions in New York, and in 1971 garnered attention for his role as Martini in the Off Broadway production of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.” He also reprised the part in the 1975 film.

He soon became a bona fide star playing Louie De Palma, the tiny-but-mighty dispatcher on the sitcom “Taxi,” which ran for five seasons from 1978 to 1983. By the time the show ended, he had met and married Rhea Perlman, known for her role as Carla Tortelli on “Cheers.” Lucy, their first child, was born in 1983. (The couple, now amicably separated, have two other children, Jake and Gracie.)

Lucy, 40, performed in school productions throughout her childhood, acting in plays like “For Whom the Southern Belle Tolls,” by Christopher Durang. In college, she said she finally admitted to herself that she wanted to be an actor. She did not expect it to be easy; if anything, she prepared for the opposite. Growing up so close to the industry, she said earlier this month, she was “very much aware of the hardships and how much disappointment there can be, how rough the business is.”

After graduating from Brown University, Lucy moved to New York City, where she played an autistic girl in an Ensemble Studio Theater production of “Lucy,” by Damien Atkins, and starred in “The Diary of Anne Frank” in Seattle, at the Intiman Theater. In 2009, she co-starred alongside her mother in a run of “Love, Loss, and What I Wore,” the play adapted by Nora and Delia Ephron from Ilene Beckerman’s memoir. (Lucy joined the show’s rotating cast first.)

In Hollywood, nepo babies, or celebrity children who coast off their family connections to get work they may not deserve, rule the screen. In New York, they’re passé. When she first began acting, Lucy fantasized about changing her last name, not wanting her parents’ reputations to precede her. (It doesn’t help that she is a perfect, even split of her parents’ faces, walking proof of the Punnett square.)

She never got far enough to decide on a name, though her father had some suggestions. Why not Nicholson? “De Niro, even,” Danny quipped.

“Lucy has always done the work,” Danny said. “I don’t think there’s ever been a time when either of us ever picked up a phone.”

The Roundabout Theater Company has now given both DeVitos their Broadway debuts. In 2017, Danny starred in a revival of Arthur Miller’s “The Price,” for which he received a Tony nomination. (Danny had to, among other things, wolf down a hard-boiled egg while speaking his lines during every performance.)

Rebeck’s play is not their first time playing father and daughter. In the 2022 animated FX series “Little Demon,” Danny was the voice of Satan and Lucy played his daughter, the Antichrist.

“I Need That,” scheduled to open on Nov. 2, will be the pair’s second production directed by von Stuelpnagel. In 2021, they collaborated on the audio play “I Think It’s Worth Pointing Out That I’ve Been Very Serious Throughout This Entire Discussion or, Dave and Julia Are Stuck in a Tree,” written by Mallory Jane Weiss, for the theater podcast and public radio show “Playing on Air.”

Lucy asked von Stuelpnagel to keep them in mind for future projects, and he connected the family to Rebeck. After a few long consulting meetings on Zoom, Rebeck wrote “I Need That” with the family in mind, even integrating small details from their lives.

Von Stuelpnagel said their interplay in rehearsals, in the same mold as their characters’ relationship, sharpened the production. “Lucy knows her father’s inclinations for certain choices he might make and she nudges him to come at it in a different way, and he listens with great respect,” he said. “That kind of collaboration is a special thing to witness.”

In one scene, Amelia shows up at her father’s house to discover that he has fallen and hit his head. She rushes to grab a bag of frozen peas for his head, checking his pupils, moving with the love of a mother and the brusqueness of a drill sergeant. It felt like both a role reversal of a familiar scene and a preview of the future: Who takes care of whom?

Though their real-life relationship inspired the play, Danny and Lucy see the differences between them and their characters, agreeing that, as a real family, they are less eccentric and less prone to yelling.

“You’re a very capable human being, and Sam doesn’t leave his house,” Lucy said to her father during the interview. “You’re one of the most social people I know. There’s a different kind of fear and exhaustion that comes from that.”

Danny agreed that he had “different problems” than Sam. “I feel blessed that I have kids who care about me enough not to write me off,” he said.

During the rehearsal process, the DeVitos sought to create a homey environment in a few ways, including, most importantly, by bringing in what Lucy called “amazing snacks.” Recent holidays on set have included cannoli Sunday, chocolate Monday and taco Tuesday.

“I’ve been on a diet since I was 10 years old, and I’m trying to figure out how to make everybody a little fatter than I am,” Lucy said. “If you’re around me, usually I’m bringing a sandwich or a nice hunk of provolone with some anchovies and some bread.”

In rehearsals, it’s hard to tell whether Lucy is talking to her father or reading lines. “They have exactly the sort of chemistry you’d expect a father and daughter to have, and that comes with playfulness, love and a history of irritations,” said von Stuelpnagel. “That familiarity breeds a really deep, dynamic relationship.”

[ad_2]

Source link

Rotary Club of Kirksville catches preview of Curtain Call Theater … – Kirksville Daily Express and Daily News

[ad_1]

Rotary Club of Kirksville catches preview of Curtain Call Theater ... Kirksville Daily Express and Daily News

[ad_2]

Source link

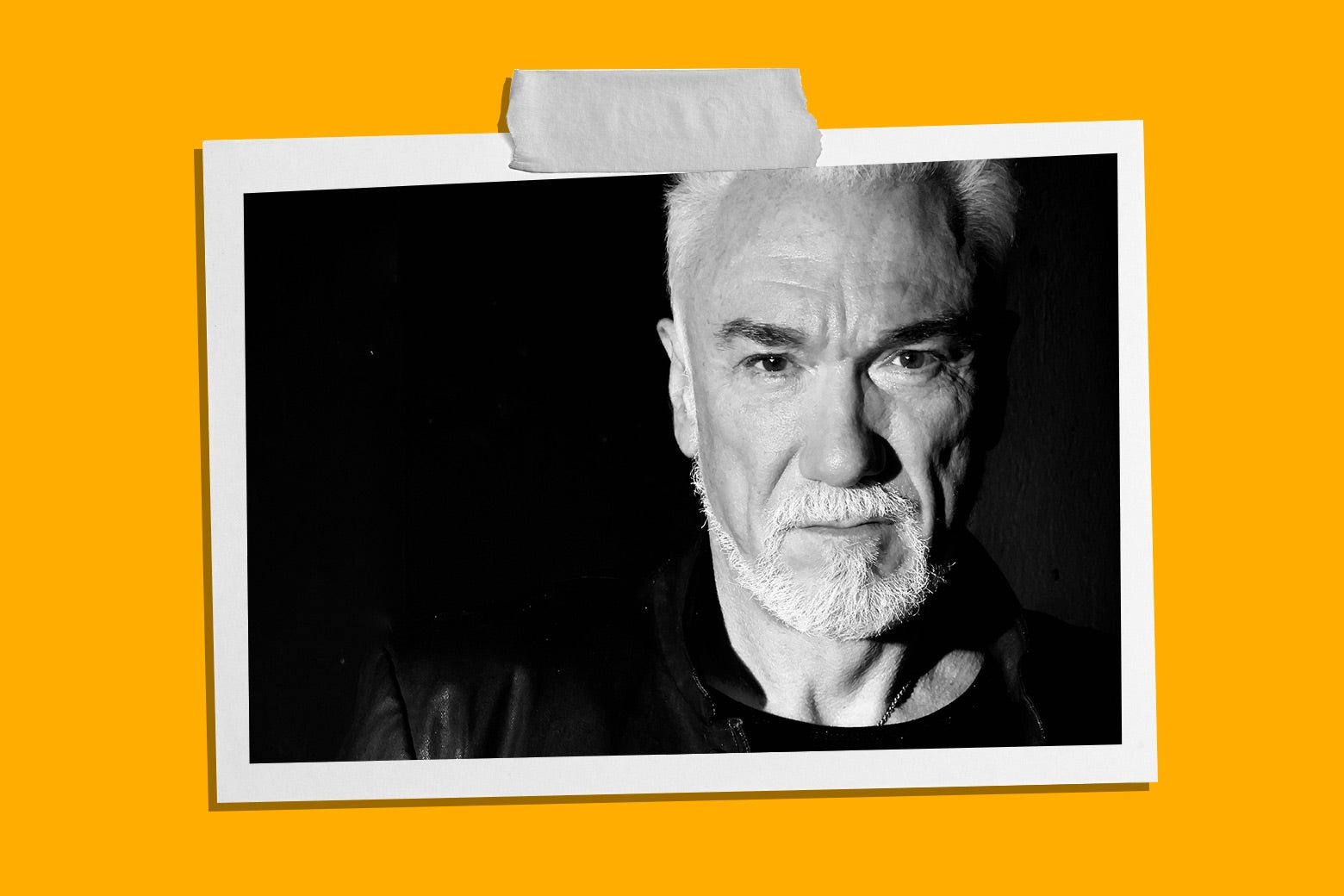

Ramin Karimloo Is The Nicky Arnstein Of Our Dreams In Broadway’s ‘Funny Girl’ Revival

[ad_1]

Ramin Karimloo has built a trans-Atlantic career for himself by reimagining the heroes of blockbuster musicals like “Phantom of the Opera” and “Les Misérables,” the latter of which nabbed him a Tony Award nomination.

But when the actor was tapped to play the dashing Julius Wilford “Nicky” Arnstein in Broadway’s first-ever revival of “Funny Girl,” he approached the project with little knowledge of its rich, and at times tangled, history.

“I didn’t know the story when I took the part, so I was very fresh coming into it,” said Karimloo, who lives in London with his wife, Mandy, and two teenage sons. “The idea of coming back to New York wasn’t necessarily what I wanted to do. But as I started reading it, I was like, ‘This is going to be a great part.’ There was a lot of meat on the bones that I could get into.”

“Funny Girl,” which is directed by Michael Mayer and opened at New York’s August Wilson Theatre last month, stars Beanie Feldstein as real-life “Ziegfeld Follies” comedian Fanny Brice. The musical charts Brice’s rise to fame in the years shortly before World War I, as well as her tempestuous romance with Arnstein, a feckless gambler.

Bruce Glikas via Getty Images

Feldstein faces the unenviable task of stepping into a role etched into the public’s memory by Barbra Streisand, who played Brice in the original stage production of “Funny Girl” in 1964 and won an Oscar for the movie adaptation four years later.

Thanks to Harvey Fierstein’s revisions to Isobel Lennart’s original book for the show, Karimloo is less restrained by the prior stage and screen incarnations of his role. The actor leans into the character’s sex appeal and, at a recent performance, drew whistles from the audience when he bared his chiseled torso at the start of the show’s second act. His Nicky gains two new solo numbers and is both a suave playboy and a tormented figure.

“In the end, Fanny and Nicky are not a great match,” he said. “But what Nicky sees in Fanny rocks his world and his perspective. He creates a facade for the world around him and has companions at the drop of a hat, but he’s not fulfilled. He wants something to protect, something deep. He’s genuinely in love.”

Born in Iran and raised in Canada, Karimloo caught the acting bug at age 12, when he was taken to see a production of “Phantom of the Opera” in Toronto. Though he’d already admired stars like Robert De Niro and Al Pacino, seeing “Phantom” was “the first time I ever felt a lump in my throat,” he said.

Over the years, Karimloo returned to the theater to catch “Phantom of the Opera” a total of 25 times. At 16, he made a bet with a friend that he’d become the youngest actor to play the title role.

“In my mind, I was already daydreaming about that character, already developing how I would play him,” he recalled. “What if he was younger? How did he get like that? I had no skills, but I had a dream.” Luckily for Karimloo, he possessed a smooth and powerful baritone voice, honed by years of performing in cover bands and in Ontario bars. In 2007, his teen dream was fulfilled when he was cast as the Phantom in London when he was just 28, about 16 years younger than actor Michael Crawford when he originated the role.

Karimloo went onto play the Phantom again in the short-lived musical sequel “Love Never Dies,” and still carries his association with that character proudly. In 2019, he joined Streisand onstage at a concert in London’s Hyde Park to perform the “Phantom of the Opera” showstopper “Music of the Night” as a duet.

And later this month, he’ll release a new EP, “The Road to Find Out: North.” The collection embraces a sound he describes as “Broadgrass,” or a mix of Broadway and bluegrass, and features a new rendition of “Music of the Night” along with a cover of the Replacements’ “Androgynous.”

Looking ahead, Karimloo said he’s eager to pursue more television and film work in addition to maintaining a presence on Broadway. In England, he starred in the BBC One series “Holby City,” and though he’s yet to be offered a similar opportunity in the U.S., he has recently completed work on the musical film “Tomorrow Morning.”

“I was a daydreamer ― I still am, more than ever,” he said. “You can make plans, and then life will just go: ‘You’re doing this.’ All I can do is absorb, keep growing as an artist. Look at Sam Rockwell and the diversity he tackles. He’s a chameleon. If I could do a percentage of what he does, that would be amazing.”

As for “Funny Girl,” Karimloo believes Brice’s “trailblazing” story, as well as her ill-fated relationship with Arnstein, will speak to a 2022 audience the same way it did some 58 years ago. Feldstein, he said, is “a gift of a scene partner” and “the quickest and most seamless partnership that I’ve had.”

“Fanny Brice didn’t wait for anything. She was like: ‘That’s what I want to do.’ So I think there’s a lot people from all walks of life, in all shapes and sizes, can take away from her story,” he explained.

“And people love complicated relationships. They like those highs and lows. Love burns more than anything, but why do we do it? Because it feels good when you’re in it and it’s worth the risk.”

[ad_2]

Source link

How one of the best Shakespeare actors prepares for a role

[ad_1]

Listen & Subscribe

Choose your preferred player:

Please enable javascript to get your Slate Plus feeds.

Get Your Slate Plus Podcast

If you can't access your feeds, please contact customer support.

Listen on your computer:

Apple Podcasts will only work on MacOS operating systems since Catalina. We do not support Android apps on desktop at this time.

Listen on your device:RECOMMENDED

These links will only work if you're on the device you listen to podcasts on. We do not support Stitcher at this time.

Episode Notes

This week, host Isaac Butler talks to Patrick Page, a broadway performer whose current one-man show All the Devils Are Here digs into the complex psyches of multiple Shakespeare villains. In the interview, Patrick discusses his passion for playing Shakespeare roles, his process for researching characters, and the importance of being a good listener as an actor.

After the interview, Isaac and co-host June Thomas talk about some specific acting exercises.

In the exclusive Slate Plus segment, Patrick shares his experiences with vocal training.

Send your questions about creativity and any other feedback to working@slate.com or give us a call at (304) 933-9675.

Podcast production by Cameron Drews.

If you enjoy this show, please consider signing up for Slate Plus. Slate Plus members get an ad-free experience across the network and exclusive content on many shows—you’ll also be supporting the work we do here on Working. Sign up now at slate.com/workingplus to help support our work.

[ad_2]

Source link

A Play Revisits the Making of ‘Death of a Salesman’ in Mandarin

[ad_1]

In 1983, Arthur Miller faced a herculean task: staging his 1949 Pulitzer Prize-winning play, “Death of a Salesman,” in Chinese, with an all-Chinese cast and crew, in Beijing.

But questions kept popping up: Would this drama about the American dream translate for a Chinese audience? Would concepts like “traveling salesman” or “life insurance” make sense to a people who had little exposure to either?

Rehearsals became exercises in cross-cultural exchange. At one point, Miller instructed his cast to abandon the wigs — he didn’t need them to impersonate Americans.

“The way to make this play most American is to make it most Chinese,” he told them, according to his 1984 book about the undertaking, “Salesman in Beijing.” He added, “One of my main motives in coming here is to try to show that there is only one humanity.”

The play eventually drew rapturous audiences to dozens of performances in Beijing, Hong Kong and Singapore, and was a watershed for U.S.-China cultural relations.

Forty years later, the process of staging that production is the subject of the Off Broadway play “Salesman之死,” running through Oct. 28 at the Connelly Theater in the East Village. (The 之死 of the title, pronounced Zhisi, means “death of.”) Directed by Michael Leibenluft and written by Jeremy Tiang, the bilingual play centers on a young Chinese professor, Shen Huihui, who interprets for Miller during rehearsals, trying to translate for the cast ideas like “the American dream.”

By spotlighting the linguistic and cultural misunderstandings between the American playwright and his Chinese collaborators, the new play explores the challenging dynamics that arose when the two cultures converged.

“This play is an example of international cross-cultural collaboration I fear we don’t see enough of,” Tiang said during a video call. “What would happen if we did try to find a way to work together, rather than just sticking to our own patch of language and culture?”

Tiang drew on interviews with the original production’s cast and crew, as well as the book in which Miller recounts traveling to China at the invitation of Ying Ruocheng, one of China’s leading actors and directors, and the playwright Cao Yu.

China had only recently emerged from its Cultural Revolution — the Maoist movement that targeted intellectuals and resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people — and its government had adopted a new foreign policy of openness to the West. Artistic projects once unthinkable under Mao Zedong suddenly become achievable.

The real-life Shen Huihui was among the first group of students to attend graduate school after the Cultural Revolution. At Peking University, Shen wrote her dissertation about Miller’s books and plays and published one of the first journal articles about Miller in Chinese. When Miller arrived in China to direct “Salesman,” Ying, who translated the script and played the protagonist, Willy Loman, asked Shen to be the rehearsal interpreter.

“I was shocked,” Shen said in a recent phone interview. “Why me? There were plenty of people who were professional interpreters, and I was not a professional interpreter.”

Meeting Miller was both thrilling and intimidating, said Shen, who now lives and teaches writing in Canada. She recalled a tall, broad-shouldered man who seldom smiled.

Rehearsals started in March and by opening night on May 7, Miller and his collaborators had worked through numerous adjustments (and endured many a misunderstanding) on the way to staging this tale about the perils of the American dream.

Those cross-cultural encounters are the core of “Salesman之死,” which is being produced by Yangtze Repertory Theater in association with Gung Ho Projects; much of the play’s plot centers on the bilingual and often chaotic exchanges within the 1983 rehearsal room.

Leibenluft first read “Salesman in Beijing” as an undergraduate studying theater and Chinese at Yale University. He later moved to Shanghai and began directing adaptations of American plays in China.

In 2017, he hosted a workshop to explore possibilities for turning “Salesman in Beijing” into a play. Tiang was among the writers and directors who attended, and he soon started writing a script.

The show eventually opted for an all-female cast, which “highlights the women who are part of this history and who are often overlooked,” Leibenluft said on a video call.

On a recent Thursday, cast members huddled around a table in a rehearsal room in Midtown Manhattan. (Five of the six actors are immigrants from China and Taiwan and are fluent in English and Chinese.) Sonnie Brown, a Korean American actor who plays Arthur Miller, barked out instructions, while Jo Mei, who plays Shen Huihui, translated them into Chinese. (The show, in English and Mandarin, has supertitles in both languages.)

The play is “so hopeful,” Mei said, describing it as a reminder of people’s common humanity: Everyone, whether Willy Loman or a shopkeeper in China, suffers the same disappointments, shares the same dreams.

“It says so much about how as different as you think you are, the themes and humanity are so similar and universal,” she said. “The more different or specific, the more universal is what I think Miller and Ying were trying to get at.”

[ad_2]

Source link

Patrick J. Adams Goes To Bat And Gets Naked In His Exceptional Broadway Debut

[ad_1]

Six years ago, Patrick J. Adams completed a monthlong run in a California production of the play “The Last Match” feeling he’d been defeated by stage fright, the kind he describes as a “hard and fast level of terror.” The experience, he said, left him convinced he’d never perform onstage again.

But this spring, the Canadian actor is confidently making his Broadway debut in the acclaimed revival of “Take Me Out,” delivering a significant portion of his performance fully naked. Most of his co-stars, including “Grey’s Anatomy” actor Jesse Williams, appear in the buff throughout the show, too.

“My initial instinct was that I couldn’t go from being the guy who was having panic attacks onstage to doing a naked play on Broadway,” Adams told HuffPost. “I thought: ‘That’s not going to work. I can’t do that. That’s too far.’”

“And then I read the script, and I knew instantly I had to do it. The play was too beautiful to deny, the opportunity was too great, and this group of people was too fantastic. I knew if I said no to this, I was saying no to theater for the rest of my life. It felt like an opportunity to heal a big wound.”

Written by Richard Greenberg and directed by Scott Ellis, “Take Me Out” depicts the New York Empires, a fictional Major League Baseball team. The team’s sense of camaraderie is put to the test when its sole biracial player, Darren Lemming (Williams), reveals he’s gay.

Adams, best known for playing Mike Ross on the USA Network’s legal drama “Suits,” stars as Kippy Sunderstrom, one of Lemming’s teammates and a confidant. The character also serves as the play’s narrator, initiating several conversations about the toxic masculinity, racism and homophobia embedded in America’s pastime.

The original production of “Take Me Out” debuted on Broadway in 2003. Greenberg has said that when he first wrote the play, he believed it wouldn’t be long before an active Major League player came out as gay in the real world. Nearly 20 years later, however, that still hasn’t happened.

Given America’s current political climate, which includes a startling pushback against LGBTQ rights in many conservative states, Adams believes Greenberg’s narrative feels more urgent than ever.

“We live in a world where more and more people are talking ― everybody’s talking ― but we still have a really tough time coming to agreement about anything that’s difficult,” he said. “Great writers write to humanity. They write to who we are, and for better or for worse, that doesn’t change as much as we’d like it to. Over time, the play reveals to us how much work we have left to do. We’ve come a long way, but there’s still so much work left.”

Bruce Glikas via Getty Images

As was the case in 2003, much of the buzz on the revival has emphasized the play’s locker room scenes, during which the majority of the cast appears nude.

“In rehearsals, we’d get to the shower scene and do it clothed. Then we did it in our underwear,” Adams recalled. “We always focused on what we were there to say. Once the water was the right temperature and all of that, we were like: ‘OK, we’re going to be naked today.’ It felt like a natural progression.”

The show’s creative team has gone to lengths to ensure no footage of the onstage nudity is shared online, and theatergoers are required to have their phones locked in sealed pouches before the curtain rises. Though Adams anticipated “hooting and hollering” when he and his co-stars dropped their towels before a live audience for the first time, he’s been pleasantly surprised by the thoughtful response.

“People see the showers coming down and they go: ‘Oh, God, this is it.’ There’s a few gasps,” he said. “You hear a little bit of shuffling and whispering and then it’s over. We’ve all seen naked bodies before, and there’s nothing highly sexual or titillating about the scene. This is not gratuitous nudity, and it’s a beautifully written scene.”

Though Adams has joked in interviews about his real-life lack of interest in sports, he’ll be spending more time on the baseball field when he returns to television later this year. The actor has a recurring role on Amazon’s forthcoming “A League of Their Own” series, created by “Broad City” star Abbi Jacobson and inspired by the beloved 1992 film of the same name.

Adams has yet to see any of the finished series, but said the tone on set was “very different from the movie, but in a great way.”

“Abbi is a genius and cut her own path through that material,” he added. “She had a very specific reason why she wanted to make it. The women I was working with were just remarkable. I think people who love the movie will also love the show, but for completely new and different reasons.”

By all accounts, “Take Me Out” is a hit on Broadway ― no easy feat in a packed theater season that continues to grapple with COVID-19 related closures and other unexpected setbacks. Last month, it was announced that the play would extend its run by two weeks, and is now slated to wrap June 11.

And if all goes according to plan, Adams hopes “Take Me Out” will be “the first of many, many Broadway experiences.”

“Theater is part of my life again. I don’t have to be afraid of it anymore,” he said. “I’m super excited to see what’s next. I’m drawn to brilliant people and I consider myself lucky if they want me in the same room. I’m looking to be of service to great material and visionary people, if they’ll have me.”

“Take Me Out” is now playing at New York’s Helen Hayes Theatre.

[ad_2]

Source link

Jon Fosse Is the 2023 Laureate

[ad_1]

The Norwegian novelist, poet and playwright Jon Fosse — who has found a growing audience in the English-speaking world for novels that grapple with themes of aging, mortality, love and art — was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature on Thursday, “for his innovative plays and prose which give voice to the unsayable.”

A prolific writer who has published some 40 plays, as well as novels, poetry, essays, children’s books and works of translation, Fosse has long been revered for his spare, transcendent language and formal experimentation.

In a news conference on Thursday, Anders Olsson, the chairman of the Nobel literature committee, praised “Fosse’s sensitive language, which probes the limits of words.”

Fosse’s work has been translated into around 50 languages and he is among the world’s most widely performed living playwrights. But he has only recently found major acclaim in English-speaking countries, thanks mainly to his fiction: “A New Name: Septology VI-VII” was a finalist for a National Book Award last year, and two of his novels have been nominated for the International Booker Prize.

He has long been tipped to receive the Nobel. In 2013, British bookmakers even temporarily suspended betting on the award after a flurry of bets on his winning, although the prize did not come his way for another decade. When it finally did, the call from the Nobel Prize’s organizers came while Fosse was traveling to Frekhaug, a village on Norway’s west coast where he has a home.

In a statement sent through his Norwegian publisher, Fosse, 64, said he was “both really happy and really surprised” to receive the award. “I have been among the favorites for 10 years, and felt sure that I would never get the prize,” he said. “I simply cannot believe it.”

Asked what he aimed to convey to readers in his work, Fosse said he hoped to impart a feeling of serenity.

“I hope they can find a kind of peace in, or from, my writing,” he said.

In receiving what is widely seen as the most prestigious honor in literature, Fosse (whose name is pronounced Yune FOSS-eh, according to his translator) joins a list of laureates including Toni Morrison, Kazuo Ishiguro and Annie Ernaux.

Critics have compared Fosse’s sparse plays to the work of two other Nobel laureates: Harold Pinter and Samuel Beckett. He’s also been called “the new Ibsen,” after the renowned Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen.

Born in 1959 in Haugesund, Fosse grew up in western Norway, on a small farm in Strandebarm. He started writing poems and stories at age 12, and has said he found writing to be a form of escape. “I created my own space in the world, a place where I felt safe,” he told The Guardian in 2014.

As a young man, he was a communist and an anarchist. He studied comparative literature at the University of Bergen. Fosse writes in Nynorsk, a minority language, rather than Bokmål, the more widely used Norwegian language for literature. While some have interpreted his use of Nynorsk as a political statement, Fosse has said it’s simply the language he grew up with.

In 1983, he published his debut novel, “Red, Black,” kicking off a remarkably prolific career. His most famous works include the “Melancholia” novels, delving into the mind of a painter having a mental breakdown; his novel “Morning and Evening,” which opens with the moment of the protagonist’s birth and ends with the last day of his life; and the seven-volume work “Septology,” an opus that runs for more than 1,000 pages and is about two elderly artists who might be the same person: One has achieved success, while the other became an alcoholic.

Jacques Testard, the founder of Fitzcarraldo Editions, Fosse’s British publisher, said his work touched on themes of “love, art, death, mourning and friendship” while “the landscape of the Western fjords near Bergen where he grew up” was almost a character in itself.

Although he started as a poet and novelist, Fosse rose to prominence as a playwright. He gained international recognition in the late 1990s with a Paris production of his first play, “Someone Is Going to Come,” about a man and a woman who have sought solitude in a remote seaside home. Fosse has said he wrote it in four or five days, and didn’t revise it.

For 15 years, he focused on the theater, and traveled widely to international productions of his plays. But then he decided to retreat back into fiction, and stopped traveling, gave up alcohol and converted to Catholicism.

A former atheist who found religion later in life, Fosse has described writing as a form of mystical communion.

“When I manage to write well, there is a second, silent language,” he said in an interview with The Los Angeles Review of Books in 2022. “This silent language says what it is all about. It’s not the story, but you can hear something behind it — a silent voice speaking.”

While Fosse’s work is sometimes formally experimental — “Septology,” for example, unfolds as a single sentence of stream-of-consciousness narration — it can also often feel immersive and gripping.

Decades of writing have taught Fosse humility, and to cast aside expectations, he said in an email interview on Thursday.

“When I start writing I never feel sure that I will be able to write a new work,” he said. ”I never plan anything in advance, I just sit down and start writing. And at a certain point, I have the feeling that the work is already written and I just have to write it down before it disappears.”

“His work can be deceptively simple,” said Adam Z. Levy, the publisher of Transit Books, a small press that began publishing Fosse in the United States in 2020, with the first of his “Septology” series. “He often writes really spare, pared-down prose, but his books catch you by surprise. They take on this really moving quality. The sentences repeat, they meander, they start in one place then come back to that at some point, kind of spiraling outward.”

Damion Searls, one of Fosse’s English-language translators, said that while Fosse has written in a range of mediums, a unifying thread in his work was a feeling of serenity, which is why his work is often described as hypnotic or evocative of a spiritual experience.

“One of the key words he uses to talk about his fiction is peace,” said Searls, who translates from German, Norwegian, French and Dutch. “There’s a real peacefulness in it, even though stuff happens, people die, people get divorced, but it radiates this serenity.”

Along with the prestige and a huge boost in book sales, Fosse will receive 11 million Swedish krona, about $991,000.

Before Fosse, the last Norwegian recipients of the literature Nobel were Sigrid Undset, a writer of historical fiction who took the prize in 1928, and Knut Hamsun in 1920.

In recent years, the Swedish Academy, which organizes the prize, has tried to increase the diversity of considered authors after facing criticism that only 17 Nobel laureates had been women, and that the vast majority were from Europe or North America. The choice of Fosse is likely to be interpreted as a step back from those efforts.

Before Thursday’s announcement, at a news conference in Stockholm, Fosse was among the favorites, although Can Xue, a Chinese writer of often surreal and experimental short stories was also tipped, as were Haruki Murakami; Salman Rushdie; and Ngugi wa Thiong’o, a Kenyan novelist and playwright.

In a statement released through his Norwegian publisher on Thursday, Fosse said he was “overwhelmed, and somewhat frightened."

When asked nearly a decade ago about his hopes of winning a Nobel, he said that while he would “of course” like to receive it, he was also wary of the burden of expectation it would bring.

“Normally, they give it to very old writers, and there’s a wisdom to that,” he said in an interview with The Guardian. “You receive it when it won’t affect your writing.”

Elizabeth A. Harris contributed reporting.

[ad_2]

Source link

Review: In ‘(pray),’ Nourish Thyself With Song and Dance

[ad_1]

Over 75 minutes, these women run through a 17-part liturgy accompanied by a pianist (Darnell White) and singer (S T A R R Busby, whose resonant voice leads the joyous gospel numbers). At one corner of this church stands a partially obscured forest. A silent spirit in white occasionally dances out from this surreal fantasy space (scenic design by dots), flitting around in fluid swells of movement. This is the Ancestor (Satori Folkes-Stone, magnetic), who also performs offstage rituals as part of the service. Another young woman, called Free (a less graceful Amara Granderson), is the one wondering whether this is a church, and if she even belongs here.

Like “What to Send Up When It Goes Down,” by Aleshea Harris, “(pray),” which douglas has nimbly written, choreographed and directed, is theater that demands the audience step into a shared experience of Blackness. In these experimental works, theater begins and ends in community.

Thus, douglas’s script aims to make faith more accessible via coy translations: “ghost” becomes “most,” for example, and “hallelujah” is “yahleloo.” The similar sounding words with the music (composed by Busby and JJJJJerome Ellis) trick the ear into fluency, so that a prayer that says “O, abundance! May I meet you. May I know you,” feels as true and traditional as, say, the Apostles’ Creed.

The Sisters deliver improvised gossip and judgmental comments, sometimes, hilariously, at the audience’s expense. The cohesiveness of their vocals and group movements (a stunning mélange of styles, including hip-hop and Afro-Cuban) recalls the deft cast of performers in Ars Nova’s 2022 hit by Heather Christian, “Oratorio for Living Things.” Each Sister sings with her own textured affect, so the psalms they perform feel creased, pleated or smoothed over like fabric. Tina Fabrique’s elastic bellows electrify “A Song (For to Ease My Troubled Mind).” Another Sister Anna (Ariel Kayla Blackwood) spits Noname lyrics atop a muscular beat. (Mikaal Sulaiman’s ethereal sound design lifts the voices higher.)

A whole syllabus of thinkers and artists have inspired (and are referenced in) douglas’s script, including the poets Tyehimba Jess and Raych Jackson. But douglas’s writing sometimes pales in comparison, lacking the same polish and panache. And there are some missed notes: “(pray)” feels more anchored within the distant and recent past, lacking firmer context in the present, and despite the production’s inclusive language around gender, queerness is only occasionally alluded to. The history of race-based attacks on Black churches, like the 1963 Birmingham bombing and the 2015 Charleston shooting, is artfully hinted at with the haunting sound of a helicopter overhead, but feels like a footnote.

[ad_2]

Source link