Category: Theater

Rediscovered: the long-lost script that helped The Great Gatsby become a classic | F Scott Fitzgerald

[ad_1]

It is the quintessential novel of the hedonistic jazz age, a roaring 20s story about the mysteriously wealthy Jay Gatsby and his love for the beautiful Daisy Buchanan. The Great Gatsby became an enduring classic, inspiring films and musicals, but received such mixed reviews in 1925 that its disappointed author, F Scott Fitzgerald, was all the more excited when it inspired a Broadway adaptation.

The 1926 dramatisation by Owen Davis, a Pulitzer prizewinner, opened to rave reviews and became a hit that contributed to the novel’s success, bringing Fitzgerald substantial royalties and fame.

But the original script had long since been lost. Now a copy has been rediscovered and will be published for the first time by Cambridge University Press – and it reveals that Davis took many liberties with Fitzgerald’s storyline.

Nick Carraway is no longer the narrator, new characters are invented, and Jay Gatsby’s past, which is revealed gradually throughout the novel, is presented all at once near the start. “Davis made some interesting changes,” said Anne Margaret Daniel, co-editor of the new publication. “He introduces some of the gangster characters who are in Gatsby’s underworld. He makes it very clear that Gatsby is in the business of organised crime, which is an apt reading of the book and, of course, it makes it more dramatic on stage.

“It’s a fascinating version of Gatsby. It absolutely captures the Jazz Age heat.”

The script had lain unnoticed for almost 100 years in a US archive. Daniel began searching for it after finding a fragment among Fitzgerald’s papers at Princeton University, along with unpublished production photographs. She eventually unearthed the complete script at Colorado State University, among papers from a study of Davis’s work that was never completed.

The script, which belonged to an actor in the Broadway staging, will be published for the first time on 25 April in the forthcoming book The Great Gatsby – The 1926 Broadway Script, edited by Daniel and James L W West III.

“It’s significant because this is the first time that The Great Gatsby was put on the Broadway stage, and thousands of people encountered the story for the first time,” said West.

“I would like to see it restaged – though The Great Gatsby is right now in the works as a Broadway musical and there’s also been an opera, a ballet and three movies at least.”

He added that, while Fitzgerald had been “protective” of the novel, he was excited by the staging, having seen an early draft and telling his agent in 1926 that it “put in my pocket seventeen or eighteen thousand without a stroke of work on my part”.

Fitzgerald had kept extensive material relating to Gatsby, and his archive at Princeton includes reviews of the novel and the Broadway production, sent to him by Max Perkins, his great editor at Scribner, and his agent, Harold Ober, as the writer was in Europe at the time.

Daniel said: “In his correspondence with Perkins, you can see that he was thrilled that it was being done. He was disappointed with the critical reception to Gatsby. He knew how good it was, but it got some stinky reviews. Some reviewers complained about the morality.”

In their introduction, she and West write that, if Fitzgerald had been allowed to attend rehearsals, “he would undoubtedly have been a pain in the neck”.

“In fact, anyone who reads the script today will probably react as Fitzgerald would have. The Great Gatsby has become a secular scripture, a verbal icon,” she said. “Many of us have read … the novel so often that we have it almost by heart. We should remember that, in 1926, The Great Gatsby was not yet a classic.”

[ad_2]

Source link

On London Stages, Uplifting Tales of Black Masculinity

[ad_1]

If you believe the Op-Eds, men are in a bad way these days: perpetually beleaguered and isolated, if not irredeemably toxic. But two lively new plays in London suggest an alternative, sanguine vision of 21st-century masculinity, foregrounding generous portrayals of male bonding and togetherness.

In “For Black Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When The Hue Gets Too Heavy,” six Black British men participate in a group-therapy session punctuated by bursts of song. The show, written and directed by Ryan Calais Cameron, is a male-centric spin on Ntozake Shange’s 1976 work, “For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow is Enuf,” in which women of color recount their experiences of racism and gendered violence through performance poetry, music and dance.

“For Black Boys” runs at the Garrick Theater in the West End through June 1. On a stage decked out in bright, blocky primary colors like a pop music video, the men — called Onyx, Pitch, Jet, Sable, Obsidian and Midnight, each a shade of black — bare their souls one by one. Every so often they morph into a ’90-style boy band, delivering neatly choreographed, crowd-pleasing renditions of R&B classics like Backstreet’s “No Diggity” and India.Arie’s “Brown Skin.” (The set design is by Anna Reid, the choreography by Theophilus O. Bailey.)

Banter is their love language. Jet (an engagingly plaintive Fela Lufadeju) is joshed for wearing chinos — a “white” affectation — prompting a spiky discussion on the vexed subject of “acting Black.” Gradually, deflection and bravado give way to introspection and insight as the men unpack the perniciousness of machismo in their lives: Jet recalls how his father refused to seek cancer treatment for fear of appearing unmanly; Sable, a self-styled Casanova (Albert Magashi, suitably strutting) concedes that insecurity might be driving his philandering ways; a flashback scene depicts Obsidian (Mohammed Mansaray) reluctantly engaging in senseless violence for street cred, with life-changing consequences.

The play ends with an upbeat mantra about keeping your chin up in the face of adversity. Its core message is about collective solidarity: By embracing emotional vulnerability and opening up to one another, young men can build support systems that will help them overcome life’s hardships. And the audience’s enthusiasm at the curtain call suggested to a sense of recognition: These sentiments rang true, and it meant something to see them conveyed from a West End stage.

But that easy accessibility comes at a price. The six characters feel like stock types, their respective travails a little too generic to be truly compelling — each existing, rather like pictures in a high-school textbook, to illustrate a trope. This is echoed in dialogue that relies heavily on melodramatic cliché (one character tells us his father was “destructive like a wrecking ball and I was the collateral damage”) and lingo taken from social sciences (“We’re not monoliths!”). Despite its exuberant energy, “For Black Boys” is ultimately somewhat two-dimensional.

Just around the corner at @sohoplace, through May 4, “Red Pitch,” written by Tyrell Williams and directed by Daniel Bailey, tells a touching story of three 16-year-old aspiring soccer players from a London housing project. As they train for an upcoming, once-in-a-lifetime tryout with a professional club, the trio engage in the daft patter peculiar to adolescence: a fizzing, complex mix of insecurity, aggression and fraternal tenderness.

Bilal (Kedar Williams-Stirling) is ambitious and driven. Omz (Francis Lovehall) is hotheaded, prone to self-sabotage; he is often unlikable, but his flaws are all too human. The goalkeeper Joey (Emeka Sesay) has the funniest stage presence of the three, whether delivering wry quips, demonstratively folding and unfolding his arms, or slipping into his father’s Nigerian accent when he’s getting worked up. The boys’ teenage mannerisms — the moody sulks and flounces, the primal urgency with which they scoff snacks — are affectionately played for laughs.

A municipal soccer pitch takes up the whole stage in Amelia Jane Hankin’s pleasing set. In contrast to another recent London soccer play, “Dear England,” where the sports choreography was less than convincing, the cast here is at ease performing sprints and passing drills. A series of dream sequences in which the boys imagine future sporting glory are strikingly rendered by spotlights, audiovisual effects conjuring camera flashes and the roar of a crowd, and the actors’ slow-motion movements. (The lighting is by Ali Hunter, the sound by Khalil Madovi.)

The poignancy of “Red Pitch” derives from the near-impossibility of a happy ending: In an ultracompetitive field, the three friends won’t all be signed by the club, and seem destined to go their separate ways. We are catching them at a specific, fleeting moment in time, on the threshold of the next phase of life. The line between sentimentality and schmaltz can be fine, but Williams’s taut script treads it nimbly. (The play’s running time is exactly 90 minutes, the length of a regulation soccer match — a nice touch.)

“For Black Boys” and “Red Pitch” are both earnest, uplifting evocations of male camaraderie by emerging British playwrights; both also achieved notable word-of-mouth success during runs in small theaters before transferring to the West End. But they showcase markedly different storytelling styles: “For Black Boys,” with its didactic enumeration of societal ills, has the feel of a PowerPoint presentation; its bracing directness befits the urgency of its message, but as a piece of art it never quite transports us. By contrast, “Red Pitch” draws us in with an absorbing — if conventional linear — narrative, and wears its wisdom lightly. The first is mere performance, the latter true theater.

[ad_2]

Source link

Years ago, Indigenous theatre was little-known. Today, plays are being produced across the country

[ad_1]

Unreserved53:59Indigenous playwrights take centre stage

It might be hard to imagine that well-known playwright Tomson Highway once had to pull people off the street to get an audience.

But that is how the Cree writer's award-winning play The Rez Sisters — which explores the lives and hopes of seven women from a fictional reserve on Manitoulin Island — started out. The play premiered in November 1986 at the Native Canadian Centre of Toronto to what could have been an empty theatre.

"Nobody knew about Native theatre, about Tomson whatsoever," said Anishinaabe playwright and author Drew Hayden Taylor.

"During the first week, Tomson and the arts administrator had to go out on the street and give away free tickets because nobody was coming," Taylor told Unreserved host Rosanna Deerchild.

But once reviews came out and word of mouth started to spread, The Rez Sisters was standing room only, Taylor recalled. In fact, The Rez Sisters was the "big bang" of Indigenous theatre, making space for Indigenous writers to follow, he said.

Today, Indigenous playwrights aren't relegated to handing out free tickets to their shows. Instead, the Indigenous theatre community has grown to sold out shows being produced across the country. This spring alone, stages in Montreal, Whitehorse, Ottawa, Saskatoon, Winnipeg, Vancouver and Toronto are all hosting plays written by Indigenous artists.

Importance of education

Education has been key to this growth, according to Rose Stella, the artistic director of the Centre for Indigenous Theatre in Toronto.

"More and more Indigenous artists are being trained. They're being educated, they're being trained [as] professionals," she said.

The Centre for Indigenous Theatre has been training young Indigenous people in theatre skills, including scene study, acting, playwriting and movement since 1974. Its three and four-year programs aim to set Indigenous people up for a career in the field.

Stella, who is Tarahumara, attended the centre as a student in the 1990s and became its artistic director in 2003.

She said she's proud of alumni who've passed through the doors of her school — like actor and producer Jennifer Podemski, who hired an almost all-Indigenous team for her latest television production, Little Bird. The series centres on an Indigenous woman, Esther, who was taken from her birth family in the Sixties Scoop as she tries to uncover her past.

LISTEN | TV series Little Bird sheds light on life during the Sixties Scoop

Unreserved54:00The Little Bird Story of the 60s Scoop

"That's remarkable," Stella said.

But it isn't just the fact that Indigenous people are learning theatre skills. Since the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which wrapped up its work in 2015, Stella has noticed more understanding of Canada's colonial history.

"People get educated and they start looking for us now," she said. "They start looking for our stories. And that's exciting."

Anishinaabe writer Frances Koncan noticed a shift in the scene when she returned to Canada after graduate school in the United States.

"I felt like the landscape had changed dramatically. … Suddenly people wanted those stories and wanted to hear these voices and see these people on stage."

Koncan is a playwright and an assistant professor in creative writing at the University of British Columbia. She is a member of Couchiching First Nation in Ontario.

Her play, Women of the Fur Trade, has had a successful ride since it premiered in Winnipeg in 2020. It later graced the stage of the Stratford Festival and sold out at the National Arts Centre in Ottawa. Women of the Fur Trade will run throughout April at Native Earth Performing Arts in Toronto.

Moving 'towards joy and celebration'

Koncan acknowledges that the humour Indigenous playwrights are increasingly bringing into their work can be a draw for theatre-goers. She says it is a shift from the work artists were putting out in the early days of Indigenous theatre, which centred on dark subjects like racism and residential schools.

One play that comes to mind for Koncan is The Ecstacy of Rita Joe by George Ryda. First produced in 1967, the play tells the story of a young Indigenous woman who leaves her reserve behind, but experiences racism and marginalization. In the end, she is sexually assaulted and murdered. Koncan says the tragedy set a precedent for what audiences should expect from plays about Indigenous people.

"Once I started really researching theatre and really taking it seriously, it was a lot of very serious, very important, very difficult plays. … They were so valuable, but they weren't plays I would necessarily want to see," Koncan said.

But she notes an "ongoing push towards joy and celebration and humour and comedy that we see, like, in our communities."

"The world is not a great place right now and I think people are turning to comedy to process things and deal with things and … step outside all of the pain and the trauma that we see," she said.

Drew Hayden Taylor's plays — mostly comedies — have been produced more than 100 times in Canada, the United States and Europe.

His new play Open House, which looks at marginalization in Canada and takes place during a real estate open house, premieres in Montreal in April. The in-demand play Cottagers and Indians opens in Vernon, B.C. in May. And in June, a German translated version of In a World Created by a Drunken God opens in Germany.

The writer, from Curve Lake First Nation in Ontario, has been in the Indigenous theatre community for decades. And he sees a bright, varied future for Indigenous stories told on the stage — from musicals and science fiction to whodunits.

"It won't all be residential schools or racism or abuse," Taylor said. "There'll be … more positive stuff that's allowed us to survive those darker aspects and are more of a broader reflection of the many, many facets of our Indigenous culture."

WATCH | Meet Kahnawà:ke's next generation of theatre kids

After a 10-year hiatus, youth theatre programming has returned to Kahnawà:ke with the Turtle Island Theatre Company.

[ad_2]

Source link

Julianna Margulies and Peter Gallagher to Star in Broadway Play

[ad_1]

The actors Julianna Margulies and Peter Gallagher are set to star in a stage adaptation of “Left on Tenth,” Delia Ephron’s memoir about a late-in-life romance.

The producer Daryl Roth said Friday that she intended to bring the play, adapted by Ephron and directed by Susan Stroman, to Broadway next fall. She did not specify a theater or an opening date.

“Left on Tenth,” published in 2022, is about how Ephron simultaneously battled cancer and found love in the years after the death of her husband and sister (the essayist and filmmaker Nora Ephron).

Ephron is a novelist and screenwriter, best known for “You’ve Got Mail,” which she wrote with her sister. She and her sister also collaborated on an earlier play, “Love, Loss, and What I Wore.”

The “Left on Tenth” team has a long list of credentials. Roth has produced 13 Tony-winning shows and seven Pulitzer-winning plays; Stroman has won five Tony Awards as a director and choreographer.

Margulies, currently starring in “The Morning Show” on Apple TV+, has appeared on Broadway once before, in the 2006 play “Festen.” Gallagher is a Broadway veteran who last starred in a 2015 revival of “On the Twentieth Century”; he has also worked extensively in film and television.

Also Friday, the producers of the new musical “Tammy Faye,” about the televangelist Tammy Faye Bakker, said their show, which they announced last fall, would begin previews Oct. 19 and open Nov. 14 at the Palace Theater. The Broadway production is to star Katie Brayben as the title character, and Andrew Rannells as her husband, Jim Bakker; the two performers previously played those roles in a production of the musical at the Almeida Theater in London in 2022. “Tammy Faye” features music by Elton John, lyrics by Jake Shears of Scissor Sisters, and a book by James Graham; the show is directed by Rupert Goold.

[ad_2]

Source link

And Now… The Scary Immersive Theatre Experience

“A scared-sounding young man told me that there was a monster in his closet. Obviously, I was supposed to tell him to open the door and look inside, so that the story could begin. But something about the darkness, the solitude, and the persuasive fear in the actor’s voice made the call feel suddenly, uncannily real.” – The New Yorker

[ad_2]

Source link

Review: Ibsen’s ‘Enemy of the People,’ Starring Jeremy Strong

[ad_1]

Dissent is necessary to democracy, sure. But how much does it cost?

That’s the fundamental question posed by Henrik Ibsen’s “An Enemy of the People” — and, in highly dramatic fashion, by the preview I attended of its latest Broadway revival.

At that performance, on Thursday, just as the play reached its climax in a raucous town meeting — and as Jeremy Strong, as the town’s crusading doctor, was trying to warn his community about an environmental disaster — members of a climate protest group secreted in the audience at Circle in the Square interrupted the action with dissent of their own.

What exactly were they dissenting from?

Surely not the Ibsen, which aligns closely with their views and is a distant source of them. (The play was first performed, as “En Folkefiende,” in 1883.) Nor does it make sense that they would object to Sam Gold’s crackling and persuasive production, which drove those views home despite having to regroup once the protesters were ejected.

After all, “An Enemy of the People,” adapted and sharpened by the playwright Amy Herzog, and starring Strong as Dr. Thomas Stockmann, is a protest already: a bitter satire of local politics that soon reveals itself as a slow-boil tragedy of human complacency.

How the satire becomes the tragedy is central to the power of Ibsen’s dramatic construction, overriding its occasional plot contrivances. To emphasize the transition, Gold begins with the warmth of gaslight and candlelight camaraderie. (The superb and varied lighting is by Isabella Byrd.) Dr. Stockmann’s home (by the design collective called dots) looks like a low-walled barge on smooth water, decorated with Norwegian blue-plate patterns. Before anyone speaks, a folk song is sung and a maid sleeps at her sewing.

With modesty and steadiness as the givens of this world, the doctor naturally does not expect to be heralded as a hero when he determines that the water supply to the town’s new spa is polluted with potentially fatal pathogens. But he does expect to be heeded.

At first, he is, at least by those who today might be labeled a progressive coterie: his daughter, Petra (Victoria Pedretti), a schoolteacher; Hovstad (Caleb Eberhardt), the editor of a newspaper that plans to publish the findings; Hovstad’s dandyish assistant, Billing (Matthew August Jeffers); and, more provisionally, Aslaksen (Thomas Jay Ryan), the newspaper’s printer.

Because this is Ibsen, the thematic complication comes in an overdetermined package. Aslaksen is also the chairman of the property owners’ association: “fanatical about moderation,” in Herzog’s pithy formulation. Hovstad is hoping to marry Petra. And the doctor’s chief antagonist is his brother, Peter, who also happens to be the mayor.

Brought to hilariously despicable life by Michael Imperioli, Peter is a stuffed shirt more interested in the sanctity of his “official hat” (a perfectly buffoonish creation by the costume designer David Zinn) than in the safety of his fellow citizens. When he learns that remediating the contamination will cost the spa’s wealthy shareholders a fortune, while shutting down the facility for several years just as it is about to welcome huge crowds, he suggests that his brother conveniently recant his findings.

From there, the play becomes a kind of crucifixion, as the doctor’s supporters peel away, each for his own seemingly reasonable reason. Peter foresees economic collapse. Aslaksen is scandalized by the likelihood of higher taxes. Hovstad, born poor, knows all too well who will be unemployed by the shutdown and forced to make good on the losses of the rich. Soon enough the progressive coterie is a reactionary mob, everyone having bitten off a discrete morsel of complaint until nothing is left to defend.

It’s too weak to say that this conspiracy of inaction makes “An Enemy of the People” relevant; its issues and ours are not similar but identical. And not just its issues. Its characters, too, are contemporary: doppelgängers of our own vicious demagogues, cowed editors, greasy both-sides-ists and defanged idealists. More than once, I thought Strong must have modeled his spectacularly accurate yet non-showy performance on Dr. Anthony Fauci, the embattled former infectious disease expert, including not just his messianic faith in science but also his barely mastered disdain, social weirdness and haircut.

Everyone in the uniformly excellent cast is complicated in that way: just wobbly enough, even in their bonhomie, to make credible the quick transformations to bad faith. The few who do not make that transformation are all the more touching for the quirks that make their good faith costly.

Of course, it wouldn’t matter how real these characters seemed in essence if they spoke like 19th-century vicars. Herzog’s clean but not noticeably modern phrasings hit just the right note. (Petra’s roast beef now “tastes great” — not “uncommonly good” as the first English translation has it.) The other alterations feel just as justified, even killing off the doctor’s wife, who had no agency, and combining her with Petra, who now has plenty. Poking fun at the doctor’s ambient sexism and largely eliminating his icky detour into eugenics are likewise improvements, as is an overall trim that reduces the playing time of the five-act play to barely two hours.

Or it would have been barely two hours on Thursday were it not for the protest. The group that took credit, Extinction Rebellion NYC, had clearly done its homework, understanding that many journalists would be on hand for the first press performance (ahead of opening night on Monday) and crafting its intervention for maximum theatricality.

Their timing, just after a pause between acts that included a surprise pop-up activation onstage, was exquisite. As part of Gold’s concept, some members of the audience who were already milling about on the set remained to “attend” the town meeting that followed. Because the house lights were deliberately left on to emphasize that mix of cast and audience — as well as the interpenetration of past and present, fiction and reality — I was certain the protest that immediately ensued was part of the show.

Certainly apt were the protesters’ costumes (statement T-shirts) and catchphrases (“No theater on a dead planet”). The cast’s ad libs in response were also on point. Still in character, Strong more than once nodded approval, saying something like, “Let the man speak.” David Patrick Kelly, as one of his antagonists, shouted, “Write your own play!”

If this had really been devised by Gold and Herzog it would have been brilliant, completing the linkage of the play’s concerns to ours, and implicating us, fairly or not, as part of the problem being dramatized onstage.

But it does not follow that, scripted instead by Extinction Rebellion, the intervention was valid or even made sense. Outshouting the doctor, the protesters seemed to be part of the reactionary mob attacking him, not like-minded citizens protecting him and underlining his warning. Even leaving aside the disregard for the actors and crew, the message, in retrospect, began to seem self-canceling.

A spokesman for the group, which previously staged actions at the Metropolitan Opera and the U.S. Open, told The Times it devises its protests to “disrupt the things that we love.” An odd way to show love! I can’t speak for the tenors or tennis players but I’m pretty sure Ibsen would have noted — indeed, he dramatizes it in this very play — that in disrupting work that champions a common cause, people who mean to do good risk making enemies of the wrong people.

An Enemy of the People

Through June 16 at Circle in the Square, Manhattan; anenemyofthepeopleplay.com. Running time: 2 hours.

[ad_2]

Source link

Pasadena Playhouse’s First Latinx Commission In Its History

The playwright is Hollywood showrunner Gloria Calderón Kellett (One Day at a Time, With Love). She says, “Latinos are 20% of the United States population, and still only 5% [of actors in leading roles], and I can’t even imagine what the numbers are for theatre.” – MSN (Los Angeles Times)

[ad_2]

Source link

Climate Protesters Disrupt Broadway Play Starring Jeremy Strong

[ad_1]

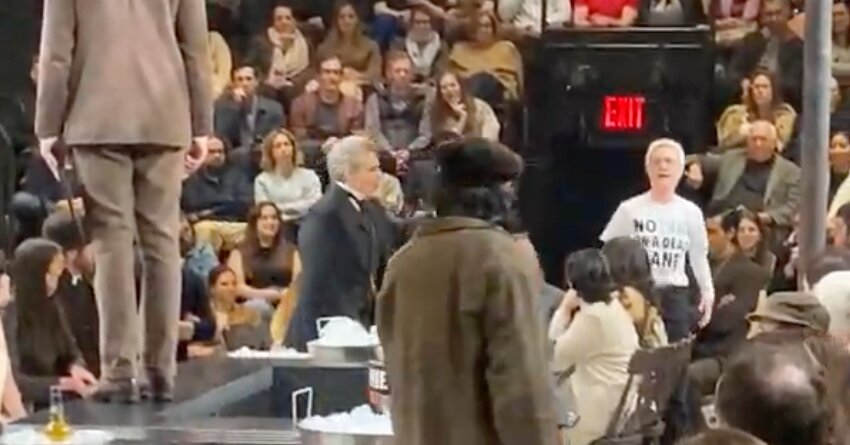

A trio of climate change protesters disrupted a performance of “An Enemy of the People,” starring Jeremy Strong, on Broadway Thursday night, shouting “no theater on a dead planet” as they were escorted out.

The show they disrupted is selling quite well, thanks to audience interest in Strong, who is riding a wave of fame stemming from his portrayal of Kendall Roy in the HBO drama “Succession.” Strong stars in the play as a physician who becomes a pariah after discovering that his town’s spa baths are contaminated with bacteria; revealing that information could protect public health, but endanger the local economy.

The protest, before a sold-out crowd at the 828-seat Circle in the Square theater, confused some attendees, who initially thought it was part of the play. It was staged during the second half, during a town hall scene in which some audience members were seated onstage and some actors were seated among the audience members. Although the play was written by Henrik Ibsen in the 19th century, this new version, by Amy Herzog, has occasionally been described as having thematic echoes of the climate change crisis.

Strong remained in character through the protest, even at one point saying that a protester should be allowed to continue to speak, said Jesse Green, the chief theater critic for The New York Times, who was among many journalists and critics who were in the audience for a press preview night. “I thought it was all scripted,” Green said. “The timing was perfect to fit into the town meeting onstage, and the subject was related.”

The protest was staged by a group called Extinction Rebellion NYC, which last year disrupted a performance at the Met Opera and a match at the U.S. Open semifinals. Other climate protesters around the world have taken to defacing works of art hanging in museums, but a spokesman for the New York group said that it had not engaged in that particular protest tactic.

A spokesman for Extinction Rebellion NYC, Miles Grant, explained the targeting of popular events by saying, “We want to disrupt the things that we love, because we’re at risk of genuinely losing everything the way things are going.”

The police were on the scene, but said they did not make any arrests after the theater’s management opted not to press charges.

The protest began when a man got up during the town hall scene and began to shout about climate change. Two of the actors in the play, David Patrick Kelly and Michael Imperioli, in character, told the man he had to leave, according to witnesses and a video of the disruption. As the first protester was escorted out, another rose up in a different section of the theater. Some members of the audience booed, and there were cheers when she was escorted out. Then a third protester sprung up.

Even though the police arrived, some audience members left the show still unsure whether the protest had been part of the performance or not.

This version of the classic play was already intended to shed light on the climate crisis, in the eyes of its creative team and stars. “In reading the play, it just ricocheted across every single thing that we’re living through and confronting, from the court of public opinion to the climate crisis,” Strong said at a press briefing last fall.

At that same event, the production’s director, Sam Gold, called the climate crisis “the animating emotional core of working on the play,” and compared Strong’s character, Dr. Thomas Stockmann, to the climate activist Greta Thunberg. “It takes a certain kind of personality to be able to say the truth,” Gold said, “to be able to say you’re all being nuts, and I am just going to tell you the truth, which is we’re destroying the world.”

This revival of “An Enemy of the People” began previews on Feb. 27 and is scheduled to open on Monday.

Maria Cramer contributed reporting.

[ad_2]

Source link