From the April 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

I f there is one mood that characterises a conversation with Kapwani Kiwanga, the Canadian artist who is representing her country at this year’s Venice Biennale, it is thoughtfulness. She speaks with a measured consideration that is all too rare in the conversation of artists. Each word is weighed, evaluated and considered before it is allowed to stand. Even then it might not be fully satisfactory to her. At one point during our conversation, I quote her own words from a previous interview back to her. She responds, ‘Maybe that’s what I said, those are probably my words, but I think my intention behind those words was…’ before recasting what she said with greater precision.

Kiwanga has built her career on the hard work of research: of exploring archives, asking questions and distrusting simplicity. Since the start of her career, she has eschewed conventional ways of telling stories as they fail to contain the complexities to which she aspires. As she says of her work, ‘Seventy per cent is research and 30 per cent is actually doing something with the research.’

She is perhaps best known for her work Flowers for Africa (2012–ongoing). This grew out of a research project in Dakar, when Kiwanga was thinking about the history of decolonisation in Africa, prompted by photos of the official ceremony marking Senegal’s separation from France. Working with florists, Kiwanga recreates the floral arrangements from the independence ceremonies of different African states and stages them in exhibition spaces. The flowers then do what flowers do: seduce, reassure, beautify, smell, rot, decay.

Kiwanga has said in a previous interview that she was ‘somewhat uncomfortable about reproducing pictures of politicians – exclusively men – in situations of power’. She also noted a further discomfort: because these photographs date from the 1960s, ‘they can feel quite nostalgic’. But to her, the flowers captured in the photos ‘had been witness to history’.

Of course, most of the photographs are black and white so the colours of the flowers might not be known. There is room for interpretation which might, itself, be a comment on history and power. For all the weighty concerns Kiwanga is placing on delicate flowers, there is something supremely elegant about such a work that enters into conversations about what she calls the ‘asymmetry of power’ through such simple material. She has described this work as ‘connecting history to nature and the nonhuman, putting political and social struggles in relation to the cycles of nature’.

Flowers for Africa (2013), Kapwani Kiwanga. Photo: Aurélien Mole; courtesy the artist and Goodman Goodman Gallery, Cape Town, Johannesburg, London/Galerie Poggi, Paris/Galerie Tanja Wagner, Berlin; © Kapwani Kiwanga/ADAGP Paris, 2023

If this sounds like an arid way of producing art, the opposite is true. Apart from anything, research is a great pleasure to Kiwanga. ‘I’m just enthusiastic about almost everything,’ she says. Born in Canada in 1978 to a family with roots in Tanzania, she studied anthropology and comparative religion at McGill University in Montreal, before moving to Paris in 2005 to study art at the École des Beaux-Arts. (Still based in Paris, when we speak, she is in Rome for a residency at the Villa Medici, part of the Académie de France.)

Kiwanga is open to the possibility of discovering dead ends: ‘I don’t think I have a cost analysis kind of approach to things – it doesn’t have to necessarily be efficient, or productive.’ This patience for just following the research where it will go seems to be partly sustained by the fact that it plays such an important role in her work. She is, however, alive to the fact that there is an effort to it: ‘I enjoy it no matter how tedious it can be, at times,’ she says.

Kiwanga’s ambitions extend to the range and scope of what she exhibits, too. In the middle of the pandemic, in October 2020, she opened ‘Plot’ at the Haus der Kunst in Munich. Social distancing put paid to some of the more elaborate elements of the exhibition – ‘there’s a lot of things that were planned around that, including performance and processions and all the rest, that we could not do,’ she says – but the physical objects were striking enough. Vast sheets of translucent fabric separated the huge rooms into defined spaces containing inflatable sculptures that encased plants and objects. Redefining the space was part of the point of the work. ‘It could have been viewed as an image on its own, how that space was transformed,’ she says.

Nowhere is space more important than in the Giardini of the Venice Biennale. Each national pavilion comes with its own architectural expression of nationhood, its own challenges and difficulties and its own history of responses to those challenges. When asked why she said yes to the commission from the National Gallery of Canada, Kiwanga replies quickly, with a laugh, ‘I didn’t think you could say no.’ This is not her first appearance at a Venice Biennale, since her work Terrarium – which developed some of the themes in ‘Plot’ – was part of the central exhibition at the Arsenale in 2022. But being part of a group show like that is a different proposition from representing your country in your own pavilion.

Despite my proddings that there is some wider geopolitical significance to the Giardini, where national styles proudly jostle up against one another – Lutyens’ tea house for the UK next to Ernst Haiger’s strident pavilion for Germany, for example – Kiwanga seems reluctant to read politics into the venue. ‘It does have that bit of microcosm,’ she says, ‘but at the same time it was built in a time and it exists in a time. I think it adjusts to something much more porous and I think that’s the reality of our kind of world and how we think about it now.’ Instead, ‘it’s quite pragmatic for me. It’s a space that doesn’t need to be given more importance than any other space.’

Installation view of Terrarium (2022) by Kapwani Kiwanga at the Arsenale during the 59th Venice Biennale in 2022. Photo: Sebastiano Pellion di Persano; © the artist

We are not able to discuss exactly what will appear in her exhibition ‘Trinket’ at Venice, such are the pressures of matching up our schedules, but Kiwanga is happy to hint that the choice of material will be an important part of it. In 2015, Kiwanga put on her first solo show in the UK, ‘Kinjiketile Suite’ at the South London Gallery. Sisal, a cash crop imported from Central America and grown in Tanzania by German colonialists, loomed large in the exhibition. Uncovering such histories is characteristic of Kiwanga’s approach to materials: Terrarium, for instance, explored the politics of sand as a by-product of oil refining and a symbol of an increasingly arid planet.

But Kiwanga is not an artist to try something and move on. Sisal makes continued appearances in her work, most notably in her sculpture Maya-Bantu (2019), recently shown in the exhibition ‘Off Grid’ at the New Museum, New York. Great screens of sisal interrupted the rooms of the gallery; an exploration of light, following research into police use of floodlights for surveillance. Venice is ripe for material metaphors, but predicting the interests of an artist who is exploring histories of toxicity during her Rome residency is a fool’s game.

Despite the combination of thorough research and profound readings of apparently simple objects, there is something bracingly practical about Kiwanga. One quirk of her history is that before her studies at the École des Beaux-Arts she relocated to Edinburgh for three years to make television. This doesn’t seem the most natural stopping point for a French-Canadian artist with aspirations to create intellectual art.

‘It’s not a good narrative,’ she says, by way of explanation, ‘it was a really pragmatic thing.’ At the time it was easy to get a visa and to find work. ‘I didn’t say Edinburgh’s where I wanted to go necessarily, but I knew I wanted to come to Europe for film-making. European cinema appealed to me more than North American cinema at that time.’ She worked as a freelancer ‘because those were some of the opportunities just to propose ideas and projects.’

It sounds almost Arcadian in its innocence and is hard to imagine some 20 years on. ‘There were these nurturing moments, these funds where you’d be paired with someone else and you would make your first little thing. And then from there, it just kept on going for a couple of years.’ This was the beginning of Kiwanga working with visual and moving images, though it was less rarefied than it might sound. ‘I was working in the social sector, doing things with youth and – how does one say – less serviced areas, so I was able to have a pretty rounded experience of, at least, that aspect of Scottish society.’

Maya-Bantu (2019), Kapwani Kiwanga. Photo: Dario Lasagni; courtesy the New Museum, the artist and Goodman Gallery, Cape Town, Johannesburg, London/Galerie Poggi, Paris/Galerie Tanja Wagner, Berlin; © Kapwani Kiwanga/ADAGP Paris, 2023

Ultimately, Kiwanga was looking for a mode of storytelling that found a more complicated and richer way of understanding things than the narrative of film and TV at that time. Though there was also the problem of who got the final cut. In one interview, she said, ‘After a few television commissions that dealt with the African diaspora, I realised I had an unsolvable problem – I didn’t get a say in the final edit and the overall message slightly changed.’

Influence and control seem to chime quite naturally with an interest in power dynamics. For an artist who is intent on uncovering the way power has worked, finding a space to say exactly what you want becomes imperative. Oddly, for an artist whose ideas are so thoroughly worked through, Kiwanga doesn’t seem to have a particular design to where her work will take her – though of course she has preoccupations. ‘It’s really just by being in a world’ that she begins a project. ‘That could be by being in a world by physically waiting for the bus, or in a park, or having conversations with people, or reading other people’s thoughts through books or whatever that might be.’

The physical aspect is something that keeps cropping up in our conversation. For all the thinking involved, Kiwanga keeps referring to the bodily experience of an artwork. Approaching Terrarium it was impossible, in the vast height of the Arsenale, not to feel the room change; not to approach the work with trepidation, slipping into the space defined by the translucent, orange fabric. But it was also exciting to enter a new world and see what was hidden behind the curtains. It was a physical as much as an intellectual response.

It becomes clear in our conversation that this is the complexity that Kiwanga is looking for. Film and television didn’t fulfil her vision because ‘there was something else that was missing in terms of the body,’ she says. ‘I think the complexity I was speaking of was really to have something that [the] body feels.’ Her academic readings are part of the work, of course, but they need to lead beyond that for a fully artistic rendering.

At one point in our conversation, while we are talking about the bodily experience of art, Kiwanga refers to people as ‘archives of experience’. It’s a beautiful image, affording each individual a dignity and richness that might easily be overlooked. I cannot help but wonder if part of Kiwanga’s excitement at going through archives is the opportunity it provides to meet new people and understand them in new ways, even if they are no longer alive. If that’s the case, then the melting pot of Venice, a city that can’t shake off its history no matter how contemporary the art it displays, seems like a particularly apt location for her next work.

‘Trinket’ is at the Canadian Pavilion, Giardini della Biennale, Venice, from 20 April–24 November.

From the April 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

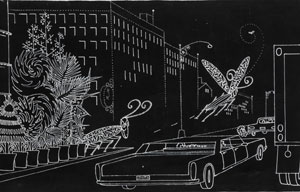

Her work recreates her life as both performance and travelogue, from desert sunlight to the darkness in her studio. When it comes to art and the powers that be, she is still pushing against the wind.

Her work recreates her life as both performance and travelogue, from desert sunlight to the darkness in her studio. When it comes to art and the powers that be, she is still pushing against the wind.  but without a trace of Renaissance idealism. In Tap Dancing from 1997, a man just shuffles his feet back and forth on the floor.

but without a trace of Renaissance idealism. In Tap Dancing from 1997, a man just shuffles his feet back and forth on the floor.