From Sample Trees, a portfolio by Ben Lerner and Thomas Demand in The Paris Review issue no. 212 (Spring 2015).

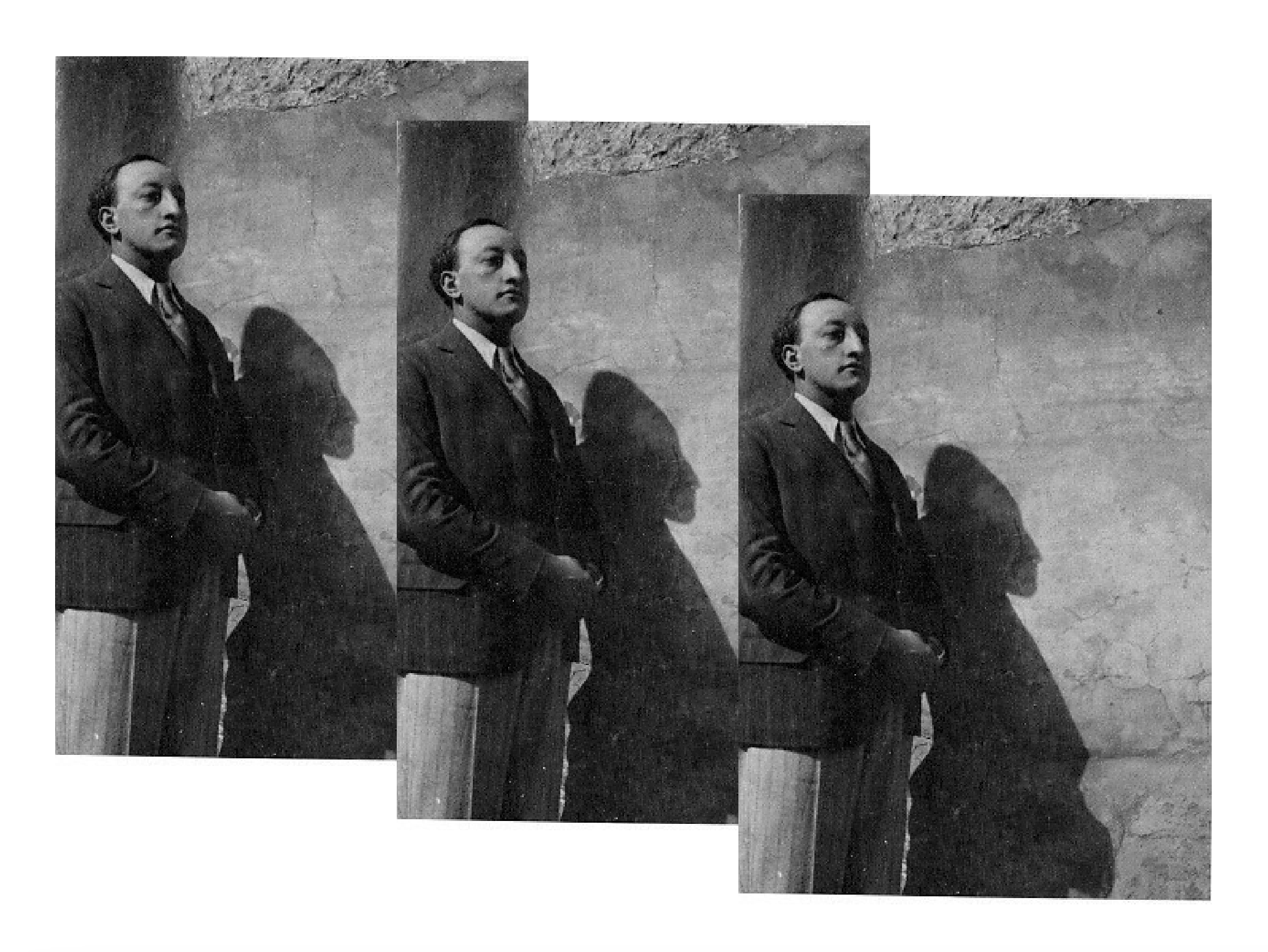

When asked if there was “a close intimacy” between him and his sister, André Weil replied, “Very much so. My sister as a child always followed me, and my grandmother, who liked to drop into German occasionally, used to say that she was a veritable Kopiermaschine.” Biographers have emphasized—overly so, according to André Weil—the episode described by his sister in a May 1942 letter to Father Perrin, known as her “Spiritual Autobiography”: “At fourteen I fell into one of those fits of bottomless despair which come with adolescence, and I seriously thought of dying because of the mediocrity of my natural faculties. The exceptional gifts of my brother, who had a childhood and youth comparable to those of Pascal, brought my own inferiority home to me.”

The largest part of the known correspondence between Simone and André Weil dates from the period when André was imprisoned for being absent without leave from his military duties; he was held first in Le Havre, then Rouen, from February to early May 1940. These circumstances gave Simone Weil an opportunity to explore scientific, and particularly mathematical, questions that were significant to her. In particular, one must note the importance given to the crisis of incommensurables in her correspondence. The reason this moment in the history of thought plays a central role at this point in Simone Weil’s reflection on science is well defined by André Weil in a letter dated March 28, 1940: “A proportion is what is named; the fact that there are relations that aren’t nameable (and nameable is a relation between whole numbers), that there have been λόγοι ἄλόγοι, the word itself is so deeply moving that I can’t believe that in a period so essentially dramatic … such an extraordinary event could have been seen as a mere scientific discovery … what you say about proportion suggests that, at the beginnings of Greek thought, there was such an intense feeling of the disproportion between thought and world (and, as you say, between man and God) that they had to build a bridge over this abyss at all costs. That they thought they found it … in mathematics is nothing if not credible.”

The crisis of reason that Simone Weil apprehended in contemporary physics led her to revisit the birth of the scientific spirit. The relationship between this crisis of science as a crisis of reason and her interest in the question of incommensurables is clear. Rationalizing irrationals was at the heart of the mathematical problem of incommensurables. According to Simone Weil’s interpretation, the same difficulty was encountered in her day with quantum theory (see her study “Classical Science and After,” as well as the article “Reflections on Quantum Theory”). How do we rationalize what appears—according to her interpretation—to be an “irrational” of this theory, in particular its uses of discontinuity and probability, notions on which the new physics rested? Could the crisis of reason, which is also a crisis of the notion of truth in contemporary physics, cause the same mental aberrations as the one produced by incommensurability, an aberration that led the Sophists to be skeptical of Logos and truth? Simone Weil’s references to Plato and her constant appeal to a new Eudoxus represent a desire to escape the skepticism of a new sophistry. She would write to her brother: “The popularization of this discovery casts discredit upon the notion of truth that has lasted to this day; it … contributed to the appearance of the idea that one can equally well demonstrate two contradictory theories; the Sophists spread this point of view among the masses, along with knowledge of an inferior quality, exclusively aimed at the conquest of power.” This marriage of a purely operative and combinatory science with the quest for power is what Simone Weil feared.

—Robert Chenavier and André A. Devaux

Saturday [February 1940]

Dear André,

I see that for the moment your morale is good. I hope this will last. Your letter brought us considerable comfort. You ask us for many details; it’s not very easy. I don’t really know what to tell you about myself; my life is currently devoid of any memorable events. I wrote an article comparing politics in ancient Rome to the events of our era for Les nouveaux cahiers [The new notebooks]; I found singular analogies, but I think I already told you about it last winter. Only the first part of the article could be published; it’s such a shame. In the course of the preparatory reading I did, I discovered someone admirable: it’s Theodoric, the one who has his sepulcher in Ravenna. Procopius, who was in the camp opposed to him, said that during his entire reign he only committed one injustice, and that he died of sorrow over it. His letters (Theodoric’s) are delightful. Aside from that there’s an article by me on the Iliad awaiting publication by the N.R.F. I don’t know what will come of it. It contains bits of translation in which I was able, for certain lines, to keep the exact order of the words; in any case I was always able to translate line by line, I mean to have one line (of irregular length) of the French text correspond to each line of verse. If you know bits of the Iliad by heart, you could try to translate them; when you use a method like this one, it often takes a half hour or more to finish a line. It’s also excellent for forming style. Translating Keats into French (in French verse, for example) must also be a fun exercise. I’ve never tried.

A good occupation when one has too much time would also be to think of a way to let laypeople such as myself glimpse what exactly the interest and significance of your work is. For even supposing that it’s absolutely impossible, as you maintain, the fact of trying surely would not be without benefit to you. The benefit would be, I think, considerable. And even if you don’t succeed in formulating something I can understand, I think I would glimpse enough for it to be extremely interesting to me. Especially since I am less interested in mathematics than in mathematicians, as with every other field.

To come back to me, lastly, to make use of those moments when my capacity for work is weak (they are frequent), I’ve started studying Babylonian. I have a selection of Assyro-Babylonian texts, with the text transcribed in Latin characters, and the translation opposite, line by line; I’m playing around with making a juxtalinear translation without a grammar or a dictionary. In this way, I made the acquaintance of a certain Gilgamesh, the hero of an epic translated from the Sumerian. Friendship is its driving spirit; Gilgamesh loses his friend and immediately starts fearing death and running through the desert looking for eternal life, but he doesn’t find it. Later, he evokes his dead friend’s shadow, which gives him not very comforting information about existence beyond the grave. I read a few words lines of it to Evelyne, who has already retained a few words of Babylonian from it. As language and as poetry, it’s far from being as good as Homeric Greek. Egyptian would be more interesting, but it’s too hard.

See you soon, I hope. I hope we’ll be able to bring you books. Do you want Retz’s Memoirs and Pepys’s Diary? I deeply hope we’ll be able to see each other tomorrow or the day after tomorrow, since it’s impossible for us to trade places, which would be my deepest desire.

Simone

[February 1940]

Dear André,

We still need to wait a little, it appears, before we have the authorization to see you as much as we would like. In the meantime, there’s nothing to do but write. But I hope that with some paper and books now, you aren’t bored, and that you exercise to keep in good shape.

Who knows, maybe you’ll discover some fascinating things? But here’s another distraction, now that you have leisure time. I don’t remember if I told you about this in the letter I wrote you from Le Havre, and that you must have received by now, but never mind. It would be to look for a way to make commoners (me, for example) appreciate the value of your current research. I’m sure this would be a very good exercise for you. What do you risk? You don’t risk wasting your time, since you have time to waste. It’s all fine and dandy for you to make fun of people like one of my former friends at rue d’Ulm who philosophize about mathematics without knowing anything about it, but perhaps it’s the mathematicians themselves who should try to do this work. Not like your friend Claude, of course. Not like the hero of Balzac’s Unknown Masterpiece when he meditates on painting. But maybe there’s a way for one to become aware of what one is doing, and the value in what one is doing. And if one becomes aware of it, it must be possible to let nonspecialists at least get a glimpse of it. What would it cost you to try? I would be fascinated.

I think you were already no longer in Paris when I managed to get a copy of the book on Babylonian and Egyptian mathematics. I don’t know if I wrote you that I was able to get it. I want to write to the author about a question he leaves unresolved, that of the means by which the Egyptians were able, with a geometry he considers extremely crude and empirical, to find a remarkably accurate approximation of π, that is to say surface area of the circle = (8/9d)^2. This seems quite easy to imagine, if one assumes the methods are very crude. If the circumscribed square is divided into eighty-one little squares, one can consider that the circle’s surface area can be found by subtracting three of these squares from each corner, plus the approximate sum of three half-squares.

There’s a truly delightful Babylonian problem. One is given the dimensions of a canal to be dug, a worker’s daily output in volume of earth displaced, and the sum of workdays and workers. One must find the number of workdays and that of workers. I wonder what students’ parents would say if an exam today included a problem formulated in similar terms? It would be fun to try it. Strange people, those Babylonians. Personally, I don’t much like this abstract thinking. The Sumerians must have been a lot more congenial. First of all, they’re the ones who invented all the Mesopotamian myths, and myths are far more interesting than algebra. But you, you must be directly descended from the Babylonians. As for me, I do think that God, as the Pythagoreans put it, is ever a geometer—but not an algebraist. Be that as it may, I was pleased, when I read the last letter I received from you, to see that you denied being a member of the abstract school.

I remember that at Chançay or Dieu-le fit [sic] you said that these studies of Egypt and Babylon cast doubt on the role heretofore attributed to the Greeks as creators in the discipline of mathematics. On the contrary, I think that so far (subject to later discoveries) they provide a confirmation of this role. The Babylonians appear to have focused on abstract exercises concerning numbers, the Egyptians to have proceeded in a completely empirical manner—The application of a rational method to concrete problems and to the study of nature seems to have been specific to the Greeks. (It’s true that one would need to know Babylonian astronomy to be able to judge.) What is singular is that the Greeks must have known Babylonian algebra, and yet one doesn’t find a trace of it in them before Diophantus (who lived, if I’m not mistaken, in the fourth century A.D.). The Pythagoreans’ algebraic geometry is something else entirely. Religious conceptions must be behind this; apparently the Pythagoreans’ secret religion made use of geometry, and not algebra. If the Roman empire hadn’t destroyed all the esoteric cults, maybe we would understand something about these enigmas.

I think I told you that I published half a study comparing ancient Rome to certain contemporary phenomena in Les nouveaux cahiers. The second part was deeply appreciated by those who had the opportunity to read it, but their numbers were very limited. The first part got me a letter that gave us a good laugh and which I’ll copy for you here:

Madam,

Reduced to immobility and not knowing “who” I could consult, I turn to you to inform me: Who are you? An article in the January 1st issue of Les nouveaux cahiers is behind this question.

Sincerely,

The signature is unknown to me. Your mother thinks it’s someone burning with a desire to avenge the Romans, and that “reduced to immobility” means: If I wasn’t reduced to immobility, I would show you. … On the off chance, I didn’t reply. I wanted to reply: And you, sir?—or else: sum qui sum—or to send a photo of myself—or a copy of my identity card. But it still seemed preferable to me to save twenty sous. He will never know who I am. The question is formulated in a truly admirable manner.

I’m only telling you about things of no interest, but I don’t find “cast-iron prose” at the tip of my pen every day.

Thank you for saying that the future needs me, but, as I see it, it doesn’t need me any more than I need it. If only I had a time-travel machine, I wouldn’t point it at the future, I would point it at the past. And I wouldn’t even stop at the Greeks, I would go at least as far as the Aegeo-Cretan era. But the mere thought takes effect on me as a mirage would on a man lost in the desert. It makes me thirsty. It’s better not to think about it, since we’re confined on this tiny planet and it will only become big, fertile, and varied again, as it once was, long after us—if it ever does again.

In the meantime, enjoy Aeschylus and the Sanskrit texts, which I hope you will soon receive.

Simone

[March 1940]

My dear brother,

I’m sending back your dedication in a slightly modified version. You’ll notice the reasons for the modifications yourself, I think. Most are prompted by concerns with logic and style, and especially the concern with preserving the unity of tone. I’m inclined to entirely cut the metaphor about sowing, wheat, etc., because it’s really not in the Louis XIII style of the whole thing, and the contrast is damaging. (Furthermore, the term plowing in this metaphor couldn’t be more unsuitable, for obvious reasons.) I slightly modified the terms of the temple metaphor, primarily for the same reason (to avoid a break in the unity of tone), and also to attenuate it and make it a little vaguer; it would prob ably be disagreeable for É[lie] Cartan, and in every respect inappropriate, for it to be written in such a way as to suggest an opposition between him, alone on one side, and everyone else on the other. In the last line, I changed one word, because your lawyer absolutely advises against leaving the one you used. Overall, I thought it wise to change a few nuances of detail that could lead ill-intentioned people to doubt whether you’re seriously expressing what you think.

Now just use these suggestions as you please, and send Henri Cartan the definitive text you’ve settled on.

I think it’s better to give up on the: “To Monsieur Monsieur …” One reader in a hundred might know this was the custom in the seventeenth century, and even he won’t think it’s serious.

We’ve given the proofs to the publisher. He’s asking for the dedication as soon as possible, of course.

I’m pleased to see that reading my friend Retz has given you a taste for that period’s style. It is infinitely superior, in my view, to that of the second half of the seventeenth century.

Fraternally,

Simone

[March 1940]

My dear brother,

Whatever you say about it, “some disquiet,” works very nicely. But discussing details of style in writing would be long and tiresome. I think your text has now reached the state of perfection, if as Valéry puts it perfection is defined by the exhaustion of the desire to modify.

How could you take my coadjutor for a Neapolitan! What blasphemy! Has anyone ever come out of there, in terms of political geniuses, other than low schemers? Doesn’t he exude Florence from every pore? And don’t you remember the Gondi Palace, in Florence, on Piazza della Signoria, set back on the left when one looks at the palace della Signoria? It isn’t adorned with much, but is most beautiful. I suppose the Neapolitan abbot you speak of is Abbot Galiani; all I’ve read by him are excerpts of letters, but I’m quite sure he had very little in common with Retz. In Mme d’Épinay’s entourage, there were only frivolous, skeptical people with low souls. While my coadjutor was first and foremost an honest man and a great soul, though that is somewhat hidden beneath the heap of adroitly intertwined intrigues. Today he might give the impression of a traitor, because in that happy period there were no political parties, and loyalty to an abstract idea, even a religious one, would have seemed utter foolishness. One was loyal to living human beings to whom one was bound by friendship, by commitments made, by the duty of protection or obedience, or by esteem. In that sense, the concern for loyalty and honor dominates all my coadjutor’s intrigues. The concern for public good also dominates them. The sense of everything he did was a desperate attempt to destroy Richelieu’s work; when he was defeated, something perished for all time. The beginning of the seventeenth century was, in France, Spain, and England, something extraordinarily luminous; an undefinable inspiration reached its peak here and perished all of a sudden, never to reappear. Personally, with the exception of Racine, I don’t esteem anything that came after 1660 (to the present day) as much as what came before. I’m not including Corneille, for whom I don’t have much esteem in any respect. But have I told you about Théophile?

Les astres dont la bienveillance

Se sent forcer de ta vaillance

Sont apprêtés pour t’accueillir;

Déjà leur splendeur t’environne;

Dieu comme fleurs les vient cueillir

Pour t’en donner une couronne

Qui ne pourra jamais vieillir.

(Ode à Guillaume d’Orange)

[The stars whose benevolence

Feels strengthened by your valor

Are ready to welcome you;

Already their splendor surrounds you;

God picks them like flowers

To give you a crown of them

That will never age.]

And this, on the civil war of 1620 (in which Richelieu was on the rebel side, by the way)

La campagne était allumée

L’air gros de bruit et de fumée,

Le ciel confus de nos débats,

Le jour triste de notre gloire,

Et le sang fit rougir la Loire

De la honte de vos combats.

[The countryside was burning

The air thick with noise and smoke,

The sky chaotic with our disputes,

The day sorrowful with our glory,

And blood made the Loire blush

With shame for our battles.]

And doesn’t this seem like the best of Valéry?

Je sentis mon sang se geler

Et comme autour de moi voler

L’ombre de ma douleur future.

[I felt my blood freeze

And as if around me there flew

The shadow of my future pain.]

He too had that sense of friendship and that generosity of soul that hasn’t been seen since that period. He wrote to Balzac: “What acquires me friends and the envious is simply the easiness of my morals, an incorruptible loyalty and the open profession I make to love perfectly those who are without fraud and cowardice.”

Naturally, he was made to suffer horribly and die prematurely. If he’d had a little baseness in his soul, he could have lived to a ripe old age, and would perhaps be regarded today as one of the two or three greatest French poets. Personally, I see Villon, Maurice Scève, him, and Racine as above all the others, and by far.

I’m not sure that the discovery of incommensurables is a sufficient explanation for the Greeks’ obstinate refusal of algebra. They must have known Babylonian algebra from the beginning. Tradition holds that Pythagoras traveled to Babylon to study there. Naturally, they transposed this algebra into geometry, long before Apollonius. Transpositions of this kind found in Apollonius probably concern quadratic equations; those of the second degree could all be solved once the properties of the triangle inscribed in the semicircle were known, a discovery attributed to Pythagoras.

(This way one finds two quantities of which either the sum and product are known, or the difference and product.) But the singular thing is that this transposition of algebra into geometry seems not to be a side issue, but the very mainspring of geometric invention throughout the history of Greek geometry.

The legend concerning Thales’s discovery of the similarity of triangles (when a man’s shadow is equal to the man, the pyramid’s shadow is equal to the pyramid) relates this discovery to the problem of a proportion whose term is unknown.

We know nothing of the following discovery, by Pythagoras, of the properties of the right triangle. But here is my hypothesis, which is certainly in keeping with the spirit of Pythagorean research. It is that this discovery comes from the problem of finding the mean proportional of two known quantities. Two similar triangles having two noncorresponding equal sides represent a proportion with three terms:

If the two extremes are constructed on a single straight line, the figure becomes a right triangle (since the angle between a and b becomes a straight angle, half of which is a right angle). The right triangle’s essential property is that it is formed by the juxtaposition of two triangles similar to it and to each other. I think that Pythagoras discovered this property first. The right triangle also provides the solution to the opposite problem: if the mean proportional and the sum or difference of the extremes are known, find the extremes.

As for conics and their properties, the inventor in this case is said to be Plato’s student Menaechmus, one of the two geometers who solved the problem of doubling the cube posed by Apollo. (The other is Archytas; he solved it with the torus.) Menaechmus solved this problem with conics (two parabolas, or a parabola and a hyperbola). So, it doesn’t seem unlikely to me that he invented them for this purpose. And the problem of doubling the cube comes down to finding two mean proportionals between two known quantities.

It’s easy to imagine the process of the discovery. For the cone consists of a circle of variable diameter, and the parabola provides the series of all the mean proportionals between a fixed term and a variable one.

So, there is a continuous series of problems: a proportion with four terms of which one unknown— a geometric progression with three terms of which the middle term is unknown—a progression with four terms of which the two middle terms are unknown.

Just as the right triangle’s properties made it possible to solve second-degree problems, those of the conics made it possible to solve those of the third and fourth.

Note that while we solve the equations by supposing that the expressions √,∛, etc., have meaning, the Greeks gave them a meaning before tackling the equations of corresponding degree.

Also note that the assimilation of the unknown to a variable goes back at least as far as Menaechmus, if not further. One can hardly suppose that the Babylonians, with their numerical equations, had this notion. The fifth-century Greeks had the notion of function and of representing functions by lines. The story of Menaechmus gives the impression that for them curves were a means of studying functions, rather than an object of study in their own right.

In all this, one sees progress whose continuity is never interrupted by the crisis of incommensurables. To be sure, there was a crisis of incommensurables, and its impact was immense. The popularization of this discovery cast discredit on the notion of truth that endures to this day; it brought about, or at least contributed to bringing about the idea that one can equally demonstrate two contradictory theories; the Sophists spread this point of view among the masses, along with knowledge of an inferior quality, exclusively aimed at the conquest of power; starting in the late fifth century, it resulted in the demagogy and imperialism from which it is inseparable, with consequences that ruined Hellenic civilization; it is through this process (to which other factors such as the Greco-Persian Wars naturally contributed) that Roman weapons were finally able to kill Greece, without any possible resurrection. My conclusion is that the gods were right to have the Pythagorean guilty of divulging the discovery of incommensurables perish in a shipwreck.

But I don’t think there was a crisis among the geometers and philosophers. Pythagoreanism was ruined (insofar as it was) by something entirely different, namely the mass massacre of Pythagoreans in Magna Graecia. In fact the star pentagon, which represents a relation between incommensurables (the division of a line into extreme and mean ratio), was one of the Pythagoreans’ symbols. But Archytas (one of the survivors) was a great geometer, and he was the teacher of Eudoxus, who is responsible for the theory of real numbers, the notion of limit, and the notion of integration as described in Euclid. There is nothing to suggest that when the Pythagoreans spoke of numbers, they only meant whole numbers. On the contrary, by saying that justice, etc., etc., are numbers, they made clear, it seems to me, that they were using this word to refer to any kind of proportion. They were certainly capable of conceiving of real numbers.

In my opinion, the essential point of the discovery of incommensurables lies outside of geometry. It consists of the fact that certain problems concerning numbers can sometimes have a solution and sometimes be insoluble; for example, that of a mean proportional between two given numbers. That alone suffices to prove that the number in the narrow sense of the word is not the key to every thing. Now, when was this realized? I don’t know if there is any information about this. In any case, it was possible to realize it before geometry; one merely needed to make a special study of problems of proportion. And in that case the geometric process to find mean proportionals (height of the right triangle) would immediately have appeared, as soon as it was discovered, as not being subject to any similar limitation. So much so that one can wonder if the Greeks might have studied the triangle to find proportions expressible other wise than in whole numbers, and if consequently they might have conceived of the line as a function from the start, as they later did with the parabola. One can find objections to this theory, but in my opinion they fall flat if one remembers the role secrecy played among Greek thinkers and their custom of only diffusing by distorting. The fact that Eudoxus is the creator of a perfect and completed theory of real numbers in no way rules out that the geometers could have glimpsed this notion from the beginning and constantly strived to grasp it.

One might ask oneself why the Greeks were so committed to the study of proportion. It’s certainly a question of religious preoccupation, and consequently (since we’re talking about Greece) a partially aesthetic one. The link between mathematical preoccupations on the one hand and philosophical-religious ones on the other, a link that is historically known to have existed in Pythagoras’s era, certainly goes back much further than that. For Plato is a traditionalist to the extreme and often says, “the ancients who were so much closer to the light than we are …” (obviously alluding to an Antiquity far more remote than that of Pythagoras); furthermore, he posted “No one enters here who is not a geometer” at the door of the Academy and said, “God is ever a geometer.” The two attitudes would be contradictory—which cannot be—if the preoccupations from which Greek geometry arose (if not the geometry itself) didn’t date back to early Antiquity; one can suppose that they come either from the pre-Hellenic inhabitants of Greece, or from Egypt, or both. Furthermore, orphism (which has this dual origin) was such an inspiration to Pythagoreanism and Platonism (which are practically equivalent) that one can wonder if Pythagoras and Plato did much more than comment on it. Thales was almost certainly initiated into Greek and Egyptian mysteries, and was consequently steeped, from a philosophical and religious perspective, in an atmosphere similar to that of Pythagoreanism.

I therefore think that the notion of proportion had been since quite a remote Antiquity the object of a meditation that constituted one of the processes for purifying the soul, perhaps the principal process. There can be no doubt that this notion was at the center of the Greeks’ aesthetics, geometry, and philosophy.

The Greeks’ originality in terms of mathematics isn’t, as I see it, their refusal to accept approximation. There is no approximation in the Babylonian problems, and for a very simple reason: it’s because they are constructed from the solutions. Thus there are dozens (or hundreds, I don’t remember) of fourth-degree problems with two unknowns that all have the same solution. This shows that the Babylonians were only interested in the method, and not in solving problems actually posed. Likewise, in the problem of the canal I mentioned to you, the sum of workers and workdays is obviously never given. They enjoyed supposing unknown what is given, and known what is not. It’s a game, obviously, that does the greatest honor to their conception of “disinterested research” (did they have scholarships and medals to stimulate them?). But it’s only a game.

This game must have seemed profane to the Greeks, or even impious; other wise why wouldn’t they have translated the algebra treatises that must have existed in Babylonian at the same time that they transposed them into geometry? Diophantus’s work could have been written many centuries earlier. But the Greeks did not see any value in a method of reasoning for its own sake, they valued it insofar as it allowed the effective study of concrete problems; not that they were avid for technical applications, but because their sole object was to conceive more and more clearly of an identity of structure between the human mind and the universe. Purity of soul was their only concern; “imitating God” was its secret; the study of mathematics helped to imitate God insofar as one saw the universe as subject to mathematical laws, which made the geometer an imitator of the supreme legislator. It’s clear that the Babylonians’ mathematical games, where the solution was given before the data, were useless to this end. What was needed was data actually provided by the world or action on the world; so what was needed was to find ratios that did not require the problems to be artificially prepared to “come out right,” as is the case with whole numbers.

It’s for the Greeks that mathematics was truly an art. Its purpose was the same as the purpose of their art, namely to make perceptible a kinship between the human mind and the universe, to make the world appear as “the city of all rational beings.” And it was really made of solid matter, matter that existed, like that of all the arts without exception, in the physical sense of the word; this matter was space actually given, imposed as a de facto condition to all of man’s actions. Their geometry was a science of nature; their physics (I’m thinking of the Pythagoreans’ music, and especially of Archimedes’ mechanics and his study of floating bodies) was a geometry in which the hypotheses were presented as postulates.

I fear that today it is rather toward the Babylonian conception that we’re moving, in other words playing games rather than making art. I wonder how many mathematicians today see mathematics as a process aimed at purifying the soul and “imitating God”? What’s more, it seems to me that the matter is lacking. There is a lot of axiomatics, which seems to be closer to the Greeks, but aren’t the axioms largely chosen at will? You speak of “solid matter,” but isn’t this matter essentially formed by the entirety of mathematical work accomplished to this day? In that case, current mathematics would be a screen between man and the universe (and consequently between man and God, as understood by the Greeks) instead of putting them in contact. But perhaps I’m disparaging it.

Speaking of the Greeks, have you heard of a certain Autran, who has just published a book about Homer? He has put forward a sensational theory, namely that the Lycians and the Phoenicians of the second millennium B.C. were Dravidians. His arguments, which are philological, do not appear to be unworthy of interest, as much as one can judge without knowing the Dravidian languages and the inscriptions he quotes. But the theory is most appealing— too appealing, even—in that it gives an extremely simple explanation of the analogies between Greek and Indian thought. Climate might be sufficient explanation for the differences. Be that as it may, how could one help feeling nostalgic for an era in which the same thought was found everywhere, among all the peoples, in all the countries, where ideas circulated over a prodigious expanse, and in which one enjoyed all the riches of diversity? Today, as under the Roman Empire, uniformity has descended upon every thing, erasing all the traditions, and at the same time ideas have practically stopped circulating. Well! Perhaps in a thousand years it will be a bit better.

Fraternally,

Simone

Translated from the French by Nicholas Elliot.

From A Life in Letters, edited by Robert Chenavier and André A. Devaux in collaboration with Marie-Noëlle Chenavier-Jullien, Annette Devaux, and Olivier Rey and translated by Nicholas Elliot, to be published this month by the Bellknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Simone Weil (1909–1943) was a French philosopher, mystic, and political activist, widely considered one of the most original thinkers of the twentieth century.

Robert Chenavier is president of the Association for the Study of Simone Weil’s Thought and the author of four books, most recently Simone Weil, une Juive antisémite?

André A. Devaux (1921–2017) was a professor of philosophy at the Sorbonne.

Nicholas Elliott is a writer and translator based in New York City. He has worked extensively in theatre in New York and France, is a contributing editor for film at BOMB magazine, and was the American correspondent for the French film magazine Cahiers du cinéma from 2009 to 2020.