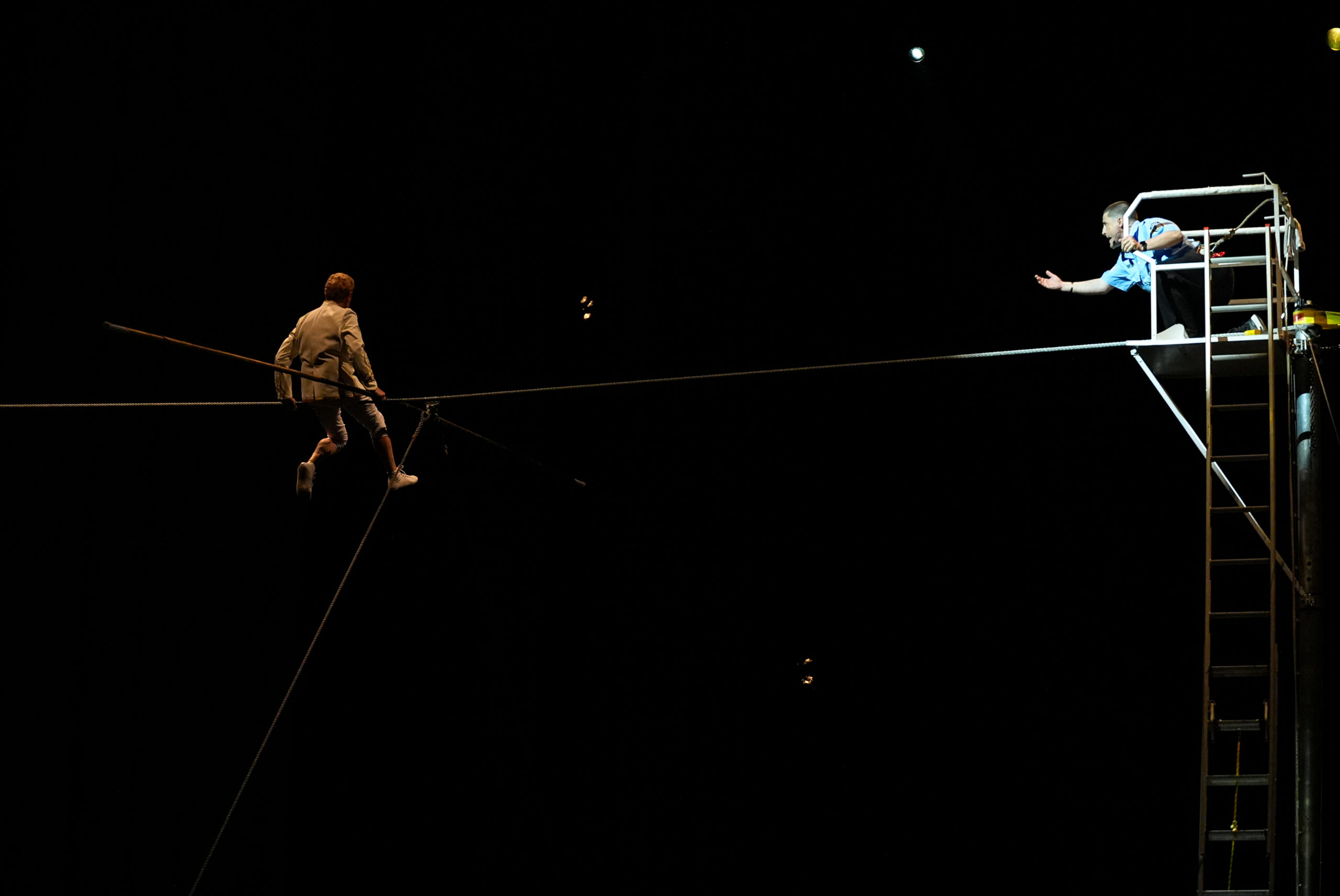

Photograph by Francesca Mantovani.

Anne Serre’s “That Summer,” which appears in the new Summer issue of The Paris Review, opens with an anticlimactic claim: “That summer we had decided we were past caring.” But the story that follows is packed with drama. Over the course of three pages, it chronicles interactions among four characters in a family—two of whom are institutionalized. There are two deaths. Serre’s narrator’s reflections on her family, charged and nuanced, are the main attraction. They bring to light entire dimensions of experience; when life has such a finely wrought interior, death is literally the afterthought.

“That Summer” previously appeared in French, in Au cœur d’un été tout en or, a collection of stories of similar brevity. That was not Serre’s first book of short-shorts, though her books available in English are made up of longer texts. They include three short novels—The Governesses, The Beginners, and A Leopard-Skin Hat—and The Fool and Other Moral Tales, a collection of novellas. All are translated by Mark Hutchinson, who is a longtime friend. Her untranslated works include Voyage avec Vila-Matas, which riffs on an experience of reading Serre’s Spanish contemporary, going so far as to feature a fictionalized version of Enrique Vila-Matas, and Grande tiqueté, written in a combination of French and a language Serre invented for the purpose. In her latest novel, Notre si chère vieille dame auteur, an elderly author whose death is imminent directs the process of assembling the manuscript that she has, already, left behind.

This interview was conducted primarily over email. A WhatsApp call was thwarted by “enormous storms” in the Auvergne region where, for two months out of the year, Serre lives, in a house that was also her grandparents’. As in Paris, she lives alone, something she has wanted since her adolescence. Asked if she would field a personal question, the author was encouraging. “Literature is personal,” she said.

—Jacqueline Feldman

INTERVIEWER

Are you in Auvergne right now?

ANNE SERRE

Yes, I am. As I’ve been doing every summer for a long time now, I’m spending two months of vacation here, in this region of mountains and small lakes, in the house I have inherited. Now that my whole family has passed away, the house belongs to me.

I don’t write here. I spend my vacation the same way I did when I was a child. I walk in the lanes and meadows, look at the scenery, swim in the lakes, and at night I read in bed. There are a huge number of books in the house—three generations’ worth. Basically, I do pretty much the same things I did when I was twelve or fourteen.

INTERVIEWER

Do you feel you need to be back in Paris in order to write?

SERRE

I don’t think it’s connected to the city of Paris. I just happen to live there for the rest of the year, and I live alone. I’ve always lived alone. My apartment in Paris is a bit like a big office, if you will. I work at my own pace, when I want, how I want, and however I please. For the time being, I’m alone in my house in Auvergne too. Not until August will some friends come for a visit. But the house is so filled with presences for me—my family, my father, my sisters, my grandparents, even my great-aunt and uncle who also lived here at one time—that there are too many people around for me to be able to write. Even if they’re only ghosts.

INTERVIEWER

Has it always been important to you to live alone?

SERRE

Yes, I always wanted to live alone. Even as a child or a teenager, when I thought about the future, I never saw myself getting married or living with someone as a couple. Which didn’t stop me from falling in love, of course. I like men and have been passionately in love, but I’ve always organized things so as not to live under the same roof as them. Since I never wanted children either, it wasn’t difficult.

INTERVIEWER

Does living alone lend itself to writing?

SERRE

Yes, I think that in my case living alone has been essential for writing. I’ve always been astonished that women writers I greatly admire could have a family life. Think of Nathalie Sarraute, for example, whose work is extremely demanding and required all her time—she had three daughters and was married. I always wondered how she managed it …

INTERVIEWER

In “That Summer,” many details of the family’s life are out of view. When the sisters don’t leave the island, Capri is described as being “petrified.” You have that title, in English, The Fool and Other Moral Tales, and I thought I might ask about morality. Even the first-person plural at the start of the story seems marked by a complicity, or the evasion of responsibility … Is it corrupting to be part of a family?

SERRE

Your question about “corruption” reminds me of Henry James, an author I’ve always loved, whose work is shot through with a strange feeling, never really explained, of something unspeakable you can’t quite put your finger on. There’s something on the moral plane that horrifies James (and perhaps horrified him during his childhood), but he doesn’t know quite what it is. In everything he writes, he’s trying to find it. This thing that horrified him, I think, is a form of inversion, the wrong side (but of what I don’t know) presented right side up or the other way around. It’s particularly noticeable in The Turn of the Screw. That’s where he comes closest to finding it. It’s what makes the book so fascinating, in fact.

INTERVIEWER

“I think, unfortunately, that I preferred him mad.” I wanted to ask you about this line, too, from “That Summer.” The narrator is referring to her father. What is the role of the perverse in your texts—if “perverse” is the right word?

SERRE

Most of my narrators use irony and self-deprecation, I think. It’s just the way my mind works. But I’ve certainly inherited this in large part from the English satirists and all those marvelous Irish writers from Sterne to Beckett, and also from Cervantes, Voltaire’s tales, and so on. I’ve always loved seditious fantasy and farce, enormities uttered with a smile, the narrator playing around with his role as storyteller and the tale being told. I like the detachment they allow in the face of tragedy—not to deny tragedy, but to bring out its grotesque side, since death will obliterate everything. That said, the narrator in “That Summer” is distinguished more by her candor. She likes the complex, conflicting emotions aroused by her father’s folly—and says so—no doubt because they allow her to perceive all kinds of interesting things she wouldn’t perceive in more straightforward, peaceful circumstances.

INTERVIEWER

There’s also a “slightly erotic” tinge to the father’s “joy” that can involve thinking he’s Alfred de Musset, George Sand’s lover. Erotic and family love occur together elsewhere in your oeuvre. Did you need both to form this story?

SERRE

I think that in everything I’ve written—starting with my first novel, The Governesses—I’ve associated Eros with joy. And also, despite its gray areas, with family love. My sense, but I may be deluding myself, is that I made a decision one day, when I was very young—I would choose joy. In the same way you might choose to live in this or that country. I imagine that the foundations must have been laid in my early childhood (otherwise I probably wouldn’t have been able to make such a decision), but later, in spite of the bereavements and difficulties I experienced, I adopted it, not as a form of “positive thinking” or as a shield against grief but because I’d noticed that siding with joy enabled me to think more clearly—to focus my thoughts. I see a bit of myself in a sentence by the Italian poet Dolores Prato, in her book Scottature. “I was in thrall to that powerful, indomitable joy that mysteriously took hold of me now and then, sometimes for no reason at all.”

INTERVIEWER

How did “That Summer” begin?

SERRE

“That Summer” began with an opening sentence that popped into my head and made me want to tell a story. When I’m writing, it’s as if I’m making a piece of furniture, a table or a beautiful wooden chair. I’m like a cabinetmaker. I love the work, so I’m always very cheerful when I’m doing it.

INTERVIEWER

Did you do many drafts of this story?

SERRE

No. In general, I write straight through, without a break. Especially stories. Then I read them over and sometimes make little changes. But the rhythm and images, I seldom change. I trust my initial impulse.

INTERVIEWER

Your stories are allusive, often featuring famous names. George Sand’s and Musset’s appear in the first lines of “That Summer,” when you’re describing the father’s illness. Can you tell me about Sand and Musset?

SERRE

I heard a lot about Musset and Sand when I was a child because my father was very fond of Musset’s work and was fascinated by his affair with George Sand. We often visited Sand’s house in Nohant. From a child’s point of view, she was a strange figure because she had a man’s name (the same name as my father) and dressed like a man. I was still at an age when you confuse reality and fiction slightly. I think that, for me, “Musset” and “George Sand” were names of characters in a fiction told by my father … and this may have left its mark … Whenever I feel love for an author—when I love someone’s work, as well as admiring its author I also feel deeply grateful to him—I have an unfortunate tendency to start thinking of him as a character in a book …

INTERVIEWER

How does reading contribute to your writing generally?

SERRE

Like any compulsive reader, my mind is full of images from the novels I’ve read. When I’m writing a story, some of these images pop into my head, get mixed up with other images from different sources (scenes I’ve experienced or imagined), and are transformed. Most of the time, I can’t really say from which specific novel such and such an image came. I might be a bit obsessed, for example, with the image of a sloping field at nightfall, with a little house at the top where the windows are all lit up, and I say to myself, Well, what do you know? I’ve seen that in a Peter Handke novel. Then later, when I’m reading over the story again, I’ll realize the image doesn’t come from Handke at all, but from an Irish novel.

INTERVIEWER

Recurring characters and settings are a feature of your work. I’m curious about Combleux—the place where, in “That Summer,” one sister is hospitalized.

SERRE

Combleux is a name I thought I’d invented, though I later discovered that a town called Combleux does actually exist in France. It’s a name I immediately associate with Proust’s imaginary town of Combray. So in a way the hospitalized sister is in In Search of Lost Time, while the father, who’s in a famous sanatorium in Switzerland, is in The Magic Mountain, or maybe in the position of Robert Walser in his Swiss asylum at Herisau.

But then the plot thickens, because not only did I discover after my book was published that a town called Combleux actually exists, but, more recently, I was invited to go and talk about my work—in Combleux! And while strolling around the town before the reading, I was suddenly brought up short by a charming riverside restaurant that I recognized at once. I had had lunch there decades before with my father and sister … Things like this happen to me now and then, and every time I’m filled with a curious feeling—a mixture of amazement, amusement, and sadness at having forgotten so much.

INTERVIEWER

Elsewhere in Au cœur d’un été tout en or, one of your characters refers to literary journalists who ask unsuitable questions. Specifically, your narrator says that they ask, “if it’s autobiographical, which of course means nothing.” Do you, too, think that a text’s being autobiographical means nothing?

SERRE

I was referring to certain French journalists who take an exaggerated interest in the biographies of living writers. I have nothing against autobiography and love reading memoirs and letters and writers’ diaries. I’m fascinated by Elias Canetti’s powers of recollection, recounting his life down to the last comma in three enormous volumes, or Stefan Zweig’s overflowing memoirs. When Gertrude Stein writes about her day-to-day life with Alice Toklas in Paris or Billignin, I’m in heaven. But I’d be hard pressed to write an autobiographical text myself because my memory is full of gaps and whole sections have fallen to pieces—as it has been, no doubt, since my mother died when I was twelve. My memory is made up of a multitude of images that are very precise but curiously naive or elementary, like playing cards, but with no connection between them and not necessarily in the right order. When I’m writing a story and one of these images pops up, I feel as if I’m turning over a card in a game of solitaire and finding a place for it among the other cards already on the table, and this allows me to construct a narrative.

INTERVIEWER

Is writing useful for remembering?

SERRE

I don’t try to remember things when I’m writing. In a way, my own life doesn’t interest me all that much, except as material. As I said before, I try to make an object, preferably a beautiful object, with a strong presence. I don’t worry at all about how inaccurate or distorted my memories might be. I embrace it, in fact.

INTERVIEWER

Since “That Summer” is a translation, I wanted to ask about that process, too. Can you tell me about your friendship with Mark Hutchinson?

SERRE

Our friendship has lasted for more than forty years now. When we first met, I was on the editorial board of a small literary magazine in Paris where I published some of my early stories. One day we decided to get together with the members of an Anglo-French poetry review that was also based in Paris. Mark was a contributor to that review. He’d come over from England, a young poet with an impressive baggage of reading and learning. As well as talking to me about authors I knew next to nothing about because they’re not much read in France, unfortunately—Blake, Yeats, Eliot, Pound, Auden, Brodsky, Marianne Moore—he talked about life in a way I’d never heard anyone talk about it before. Over the years, as a result of our more or less continuous dialogue, not only the English-speaking world and its culture but a particular form of knowledge Mark possesses have become part of me, opening up my inner world. It never occurred to me when we met (or even twenty years later) that one day, Mark, who mainly translates poetry, including René Char and Emmanuel Hocquard, would translate my books into English. But a few years ago, when the editor in chief of New Directions, Barbara Epler, decided to publish The Governesses in English, our friendship set off naturally down that path.

INTERVIEWER

What can prose do that poetry can’t? What draws you to writing narratives?

SERRE

To tell the truth, I’m more familiar with prose than with poetry, much of which is inaccessible to me, I’m sorry to say. Whereas Mark’s enormous library contains not only poetry, fiction, and essays but philosophy, anthropology, psychoanalysis, and so forth, my own library consists almost entirely of novels, short stories, writers’ diaries and memoirs, a handful of plays (which I prefer reading to seeing performed onstage), and plenty of monographs about painters, which I look at when I’m feeling poorly or am laid up in bed with flu. There’s only one shelf of poetry. I like having those books and seeing their covers—Emily Dickinson, Anna Akhmatova, Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Every once in a while, I open one up, read a few pages, and tell myself, like Rabelais, that this is the “substantific marrow,” but I’m not spellbound the way I am by fiction. I’ve noticed in fact that I tend to read everything as if it were fiction. If I’m reading The Memorial of Saint Helena, for example, I think of Napoleon as a character. If I pick up Winnicott’s The Piggle, I think of the little girl as Alice. With Saint-Simon’s Memoirs, I think of characters from the commedia dell’arte …

Mark once said to me (and I remember this because I wrote it down in a notebook, and I always remember what I write down in my notebooks) that poetry is a way of grasping seemingly disparate facts that are grouped together because they’re part of the same species. That for Marianne Moore it was “imaginary gardens with real toads in them,” and for Basil Bunting, “words that name facts dancing together.” So I get the general picture. For my part, however, I need to be told a story, and I need there to be, at the heart of that story, a dangerous, mesmerizing well or passageway, as there are in most great works of fiction. It’s this passageway that attracts me. As I approach it (in reading), I feel something very powerful, a bit like Ulysses with the Sirens, if you like! And I’m sorry I can’t be more precise in describing that passageway—its nature, its function. Perhaps I try to understand it by writing …

Jacqueline Feldman’s On Your Feet, a bilingual experiment, was published in March by dispersed holdings. Precarious Lease, her account of a Parisian squat, is forthcoming from Rescue Press this fall.

That can be a problem. Martiel can seem a one-note artist, and the note can ring all too clearly or hardly at all. He can also turn you away.That can be a strength, too, and critics must have brought the same complaints to Burden long ago. Martiel addresses Cuba’s repressive state honestly as well. He pins three of its medals directly to his chest—medals awarded to his father before him.

That can be a problem. Martiel can seem a one-note artist, and the note can ring all too clearly or hardly at all. He can also turn you away.That can be a strength, too, and critics must have brought the same complaints to Burden long ago. Martiel addresses Cuba’s repressive state honestly as well. He pins three of its medals directly to his chest—medals awarded to his father before him.