Writing Process Blog Tour

Thanks so much to Daniela Cascella for inviting me to take part in the Writing Process Blog Tour. Daniela’s writing, which you can read in her blog as well as in her fantastic book En abîme, is hugely influential for me. I strongly identify with the way she uses language and her interplay of personal memory and sound, of culture and history.

Here are my answers:

What am I working on?

I am currently in a very busy period with quite a substantial amount of commissions for various types of publications and exhibition spaces, which include essays, interviews and reviews. So for the the past three months I have focused on meeting all these deadlines while maintaining the highest possible standard of writing. Whenever I have to produce a lot of writing in a small amount of time I worry about the quality of my texts: repeating myself, running out of fresh ideas and so on. There is always this little paranoia lurking in the back of my head, which adds to the stress of meeting deadlines.

This is why I am very much looking forward to my summer holidays so I can focus on a couple of personal projects that will demand quite a lot of uninterrupted time. The first is a long-form essay which will explore the use of interior and domestic spaces across the fields of film and visual arts to convey psychological states and address issues related with class, domesticity and creative aspirations. The second project could become my first novel (!). I am on the very very early stages of researching and note taking, so it wouldn’t be immediate, but the ideas and the urge are there. I haven’t got the slightest idea of how to write a novel, having written in various short forms up until now, so I still have to develop a methodology of sorts. At this point, however, I just want to sit down and write, and see where that takes me.

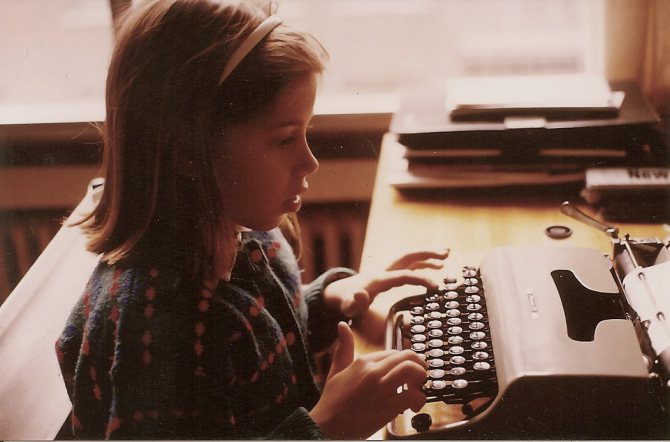

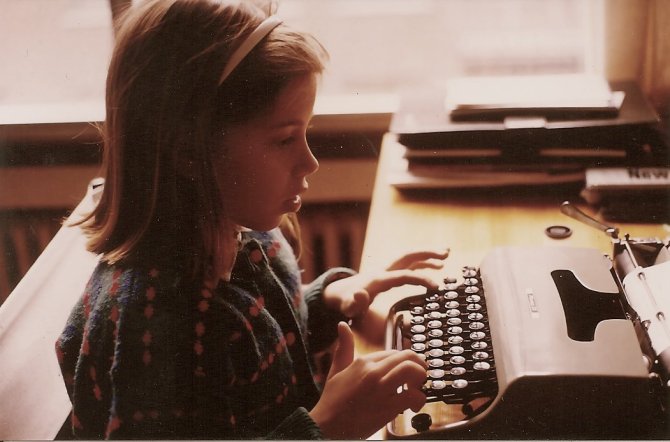

Me, writing god knows what at 8 or 9 years old

How does my work differ from others of its genre?

I have no idea of how my work differs from others of its genre. That is probably not for me to say! I can only say that one of my pet hates involves art writing that sounds very complicated and lofty, but which is just masquerading a total lack of content and personal ideas. I guess that can actually be applied to any sort of writing. I like writing that contains and discusses complex ideas but that manages to do so in an accessible, readable manner. I strive for my writing to be like that.

What do I write what I do?

I have always considered myself a writer, since I was a small child. I started writing short fantastic stories when I was 6 or 7 years (I actually wish I could find those manuscripts, typed with a red Olivetti type writer my brother gave me as a present). When I was a teenager I went through a heavy poetry phase, and all wrote was poetry, which I sort of understood as lyrics to songs I never wrote (yes, I am frustrated musician). I then became a journalist and then I specialised as an art critic, which I have been for a few years now and which is a format that I adore and feel very comfortable with. Art writing is elastic enough to allow and welcome different approaches, even rather experimental, and I can address not just art but also film, critical theory, philosophy and music, which is basically what I want to write about, so I feel very happy about having found this outlet and carved my niche. However, fiction beckons. I have been wanting to write fiction in the form of a novel for pretty much a decade, but it really wasn’t the moment. I feel ready now, I just need the time, which is why I have started applying to writing residencies. It is the first time that I actually have the need for them. What I mean is that I don’t feel tied to any particular type of writing, I feel that the form my writing takes is just an adaptation to my needs and aspirations in different moments. What prevails is an urge to write; to read, to think and to write about art, culture and subjectivities. My ideas for my prospective novel address the same concerns as my art writing. It makes no difference to me.

How does my writing process work?

There are two ways to respond to this question. The first one would be to explain how I write. And the thing is, I don’t have a very strict methodology in place, it varies depending on the particular texts I am facing. After all these years at it, I am very disciplined when it comes to writing and I can manage to just sit down and write on a daily basis, which helps a lot. I am extremely responsive to stimulus though, so I usually benefit from exposing myself to a lot of reading, exhibition seeing and film watching when I have to write. When I am very busy with deadlines and I have to chain my leg to my desk, I barely have time to “nurture” myself in that way and I become quite despondent about it. I need good inputs to produce decent outputs. I believe in intuition, so sometimes I sit to write with absolutely no idea of how am I going to go about it. It just happens. I have never really suffered from “blank page fright”. I am a terrible public speaker, I get nervous when I have to talk or present to an audience, but when I am writing I always feel ok. I might hate what I have written on a given day and delete or re-write most of it, but I am already “in process”, and eventually I will get to something I am pleased with (hopefully). I always, always, write on my computer. I carry a notebook with me at all times and I take lots of notes, and sometimes I will even draft structures for pieces. But once I sit down to write I will barely look at them or use those structures. When I write I inhabit a brand new place, with unpredictable results. When I am working well, I am “riding the wave”. When nothing good comes out, I get mildly depressed or rather cranky, but I keep writing, just in case I can get “to the wave”. I always, always write to music, since I was little. It is very important for me and really determines the mood of what I produce. It usually is experimental, electronic or classical music. It has to be instrumental music, no words. Steve Reich is pretty much my usual soundtrack of choice. Or Eliane Radigue. I play minimal, repetitive music because it gets me to a focused, productive place.

The second way of answering has to do with a new methodology I have developed. When I wrote my text on Eliane Radigue I discovered a way of writing about art, music and historical characters I am interested in which combined fact and fiction. It mixes the genres of essay and fictionalised biography. I am not quite sure how to define it, but I know it’s definitely not new. Some people have pointed an affinity between this particular text and the writing of W.G. Sebald, which both pleases me and humbles me no end. I consider Sebald one of the most gifted, compelling and poignant writers of the 20th century, so I don’t feel worthy of that comparison. In any case, it was incredibly liberating to find a way to write a fiction of sorts while keeping all of my factual and artistic interests in the text. It has given me a much-needed boost of energy and confidence to face my (hopefully imminent) fiction writing.

![]()

SOURCE: SelfSelector - Read entire story here.