A young Henry James, writing about Nathaniel Hawthorne in 1879, notoriously remarked, “One might enumerate the items of high civilization, as it exists in other countries, which are absent from the texture of American life, until it should become a wonder to know what was left.” For James, Hawthorne’s country had been a void, as immensely small, you could say, as it was big (which presented a daunting prospect for the writer), but certainly different from the clearly marked boundaries of nation and class that European writers had been accustomed to patrolling and negotiating. The problem of America is in effect a problem of scale and measure, not just how to measure the immeasurable but how to measure up to it, and in that way it anticipates the problems of accounting for the unaccountable that confronted the twentieth-century novelist. Gertrude Stein, twenty-six as the century began, saw this as clearly as anyone. America, she wrote in 1932, is “the oldest country in the world because by the methods of the civil war and the commercial conceptions that followed it America created the twentieth century, and since all the other countries are now either living or commencing to be living a twentieth century life, America having begun the creation of the twentieth century in the sixties of the nineteenth century is now the oldest country in the world.” In this nicely gnomic pronouncement there’s the wit of Oscar Wilde as well as—looking at the Civil War as method—an almost Leninist realism and sangfroid, not to mention the familiar twang of American self-promotion. It is a characteristically insightful and provocative comment from a brilliant woman who grew up in America with an ineradicable sense of the foreignness of her German Jewish immigrant family and went on to live all her adult life as an American in Europe. Stein, of course, was not in any sense alone in seeing America as a central presence in the new century—the American Century, as it would be called by many people with varying degrees of hope, resentment, and dread—but she was unusually sensitive and responsive to American formlessness. She found, not without a good deal of searching, a way of working with it that worked for her. In doing that, she also helped to transform not only the American novel but the twentieth-century novel.

Stein began in an unlikely, lonely place. The youngest of five children of Daniel and Amelia Stein, first-generation German Jewish immigrants and members of a prosperous merchant family, she grew up between America—she was born outside of Pittsburgh in 1874—and Europe, to which her restless father removed the family for a spell of years almost immediately after her birth. She grew up between continents, and she grew up among languages, speaking German (the language of her home) and French before English, which she initially picked up from books, and once back in the States, she grew up between the coasts. The Stein family was largely settled in Baltimore, until Daniel decided he’d be better off in Oakland, of which Stein would famously quip “there is no there there.” In a big house on the sparsely settled suburban outskirts of the expanding western port, Stein’s mother fell ill and slowly died while her father grew ever more irascible and demanding, and Stein buried herself in books: Shakespeare, Trollope, A Girl of the Limberlost.

Daniel died suddenly in 1891 and was neither mourned nor missed. His son Leo, to whom Gertrude was close, went east to Harvard; Gertrude followed him to attend classes at Radcliffe, where she studied English literature and took an interest in psychology. Henry James was a favorite writer of hers, and his older brother, the psychologist and philosopher William James, now became her teacher. He made a strong impression, and she impressed him; he encouraged her scientific ambitions, urging her to go to medical school at Johns Hopkins at a time when few women had MDs and those who did were often unable to practice. Leo was already at Hopkins, pursuing a degree in biology, and Stein joined him at the university, but instead of studying, she fell in love with a fellow student named May Bookstaver and became entangled in a tormenting lesbian love triangle. Leo left for Europe, in order to learn “all about art” at the foot of the famous connoisseur and socialite Bernard Berenson; escaping Bookstaver, Gertrude once again set out after him. At Berenson’s house in England, Leo and Gertrude met and argued about politics with Bertrand Russell, and Gertrude stayed on through a bone-chilling London winter. But then she went back to Baltimore and Bookstaver, only to flunk her qualifying exams. A medical career was not to be.

She wanted, in any case, to be a writer. Imitating Henry James, she wrote a novella called Q.E.D., about her relationship with Bookstaver, that she promptly packed up and forgot about. Then she started a novel about a German-Jewish American family like the Steins. It was to be called The Making of Americans, and it seems to have begun conventionally enough, until Stein, apparently dissatisfied with the results, had another idea. Recalling some of the research she had conducted under William James, she decided that her novel should constitute not just a family history but a comprehensive inventory of every type of human character. “I began to be sure,” Stein would remember, “that if I could only go on long enough and talk and hear and look and see and feel enough and long enough I could finally describe really describe every kind of human being that ever was or is or would be living.” This was certainly an unusual project, but the more Stein pursued this encyclopedic butterfly, the farther out of reach it flew. She would come back to The Making of Americans in time, completing it after almost a decade—an immense work—and she would always promote it as her greatest achievement. She did not hide what a struggle it had been. Years later, as a traveling celebrity in America, she delivered a lecture on “The Gradual Making of The Making of Americans,” and the quotes she culls from the book’s pages are telling: “I am altogether a discouraged one. I am just now altogether a discouraged one … I do a great deal of suffering.”

It was 1905, and Stein had picked up and followed Leo to Paris, but in a sense she was still where she had always been: betwixt and between continents and languages and caught in the thick of family. Leo, however, had at last found his calling: having discovered Cézanne, he set up as a “propagandist” for modern art. Leo and Gertrude and their oldest brother, Michael, who looked after the family business and had also come to Paris, were all busy collecting the work of young artists, and they were surrounded by them—Matisse and Picasso were their friends—and absorbed in questions about art and innovation and the somehow related question of their Americanness, which defined them in their own and others’ eyes. (“They are not men, they are not women,” Picasso said of the Steins. “They are Americans.”)

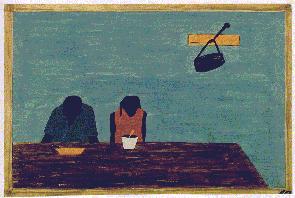

And for Stein of course there was the question of her own character and loneliness and work. Leo suggested that she translate Flaubert’s Three Tales, a literary touchstone of the turn of the century. The task would improve her French and perhaps give her ideas. It did, but not in the way Leo intended. “A Simple Heart,” the most famous of Flaubert’s Three Tales, tells the simple story of the life of a French servant woman. No, Stein would not translate it. She would write three lives of her own: American lives—American lives and women’s lives and lives that all bear a certain resemblance to the life of Gertrude Stein. The lives of the Gentle Lena and the Good Anna bookend Stein’s collection. These are poor German immigrant women toiling away dutifully as servants all their life long, their gentleness and goodness as much bane as boon. In the middle is the story of Melanctha, a “complex, desiring” young woman, a searcher. Melanctha is Black and, by the conventional standards of Stein’s day, not good at all. All three women live in a fictional American city called Bridgepoint (which is to say neither here nor there, but on the way to somewhere, the American situation par excellence), and all three are poor and, though very much American, in another sense, not: foreign-born, Black, speaking nonstandard English, they are very much outsiders, just like their creator in Paris.

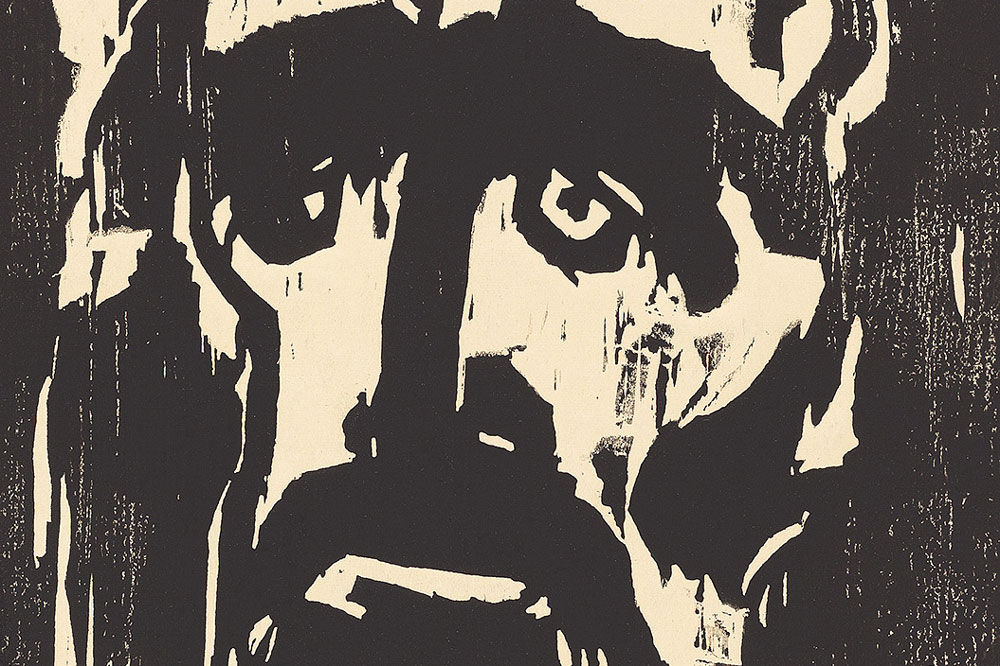

“Melanctha” is the longest story in Three Lives, and it was in telling the story of Melanctha that Stein discovered herself as a writer. Melanctha is the child of parents who resemble Stein’s—the father angry and threatening until he simply disappears from his daughter’s life, the mother present only in her being interminably ailing—and the story starts when she is a teenager, avid to find out what she can about life. Hanging out at the train station, she finds out something about sex and men. She finds out more about sex and men from an older woman, educated, experienced, hardened—her name in fact is Jane Harden—who takes her under her wing and perhaps into bed, and then she begins to find out about love from the young doctor attending to her mother. Jefferson Campbell is very much the opposite of the mercurial Melanctha—he is “very good” and “very interested in the life of the colored people”—but then opposites attract. Melanctha and Jeff grow close—he is infatuated—yet when Melanctha hints suggestively at her sexual history, Jeff turns jealous. Melanctha resents what she encouraged, and the relationship turns into a torment. Melanctha and Jeff break up, and she takes up with “a gambler, naturally a no-good.” Depressed, Melanctha comes down with TB and dies. “Melanctha” is done.

The story is quickly told and in a sense not much of a story at all. Sometimes it seems like a nineteenth-century cautionary tale about how bad girls come to a bad end, or perhaps a tongue-in-cheek send-up of such a tale. At other times it might be taken as the story of a good person whose life is blighted by racial prejudice and social intolerance, a sad story, though told with a certain off-putting ruthlessness. “Melanctha all her life did not know how to tell a story wholly,” Stein writes, as if preparing the way for her premature demise. In places, it appears to be a kind of modern fairy tale, almost willfully naive, while elsewhere and quite differently it comes off as a near clinical examination of the psychological dynamics of love, not unlike the sorts of things Marcel Proust and D. H. Lawrence were starting to write at around the same time.

“Melanctha” is all those things and none of those things, and sometimes it seems like it is really nothing much at all. The main reason it’s so hard to pin down what “Melanctha” is getting at is that the story is so very long in the telling, not to mention the ever more peculiar language in which it is told. “Melanctha” is 120 pages long, composed in a manner that might be best described as conspicuously wordy:

Life was just commencing for Melanctha. She had youth and had learned wisdom, and she was graceful and pale yellow and very pleasant, and always ready to do things for people, and she was mysterious in her ways and that only made belief in her more fervent.

What wisdom had she learned? What did she do for other people? Whose belief is it that grew more fervent? Her own beliefs (in what?) or others in her? (Both readings are possible.) “Melanctha” is full of vague sentences like these—filled out with conventional descriptions and polite nothings and sentimental or racist turns of phrase like “the wide, abandoned laughter that makes the warm broad glow of negro sunshine”—and as it goes on, those sentences tend to grow longer and more and more and more repetitive:

“Melanctha Herbert,” began Jeff Campbell, “I certainly after all this time I know you, I certainly do know little, real about you. You see, Melanctha, it’s like this way with me … You see it’s just this way, with me now, Melanctha. Sometimes you seem like one kind of a girl to me, and sometimes you are like a girl that is all different to me, and the two kinds of girl is certainly very different to each other … I certainly know now really, how I don’t know anything sure at all about you, Melanctha.”

“I certainly know now really, how I don’t know anything sure”: I am not sure that Stein knew for sure what she was up to as she hit on this style, which—with its limited vocabulary, ever-expanding paratactic sentences, and repetition compulsion—might be dismissed as both flat and flatulent, maddening and even perhaps a bit mad, but as “Melanctha” proceeds becomes ever more recognizable and unignorable. Stein may have been up to a number of different and not, at first sight, necessarily compatible things. Here she is finding words at last to tell her own story, the Bookstaver story. Bookstaver would later remark that Jeff and Melanctha’s grinding exchanges were little more than transcripts of hers with Stein. In that sense, the language of “Melanctha” might be considered symptomatic on the one hand and therapeutic on the other, a way for Stein to get something off her chest and put it behind her. Then again, she is also finding words to tell the story of a woman, Melanctha, deprived of the authority or capability to tell her own story, someone whose sex and race and life place her outside the space of “proper” storytelling. To that extent, her writing of Melanctha is as public and political as it is private and therapeutic. Though Stein was never an overtly political writer—she didn’t do messages—and her actual politics involved an unsavory fascination with such putative strong men as Napoleon and Marshal Pétain, she was alert to politics (those “methods of the civil war”) and to the political nature of language.

In the end, however, “Melanctha” is not so much about telling anyone’s story as it is about putting story aside. Here, Stein, trained in scientific experiment and emboldened by the experimentation of the artists around her, turns from story to take a new look at what stories are made out of: language, sentences, words. “Melanctha” is written out of an intense, even desperate awareness of how language shapes experience—its imprecisions, its evasions, its formulae, its structure, its unavoidable limitations. She takes, for example, the clogging –ings and jingly –lys intrinsic to the English language, and instead of playing them down, as “good” writers have long been taught to do, she lets them loose. Is what results “bad” writing? It is writing that tends toward a drone, and a drone is perhaps the tone of boredom, depression (the melancholy inscribed in Melanctha’s name). Certainly, to echo Stein, one of the things this sad tale of an unrealized life is designed to do is to make the reader feel language and also feel language fail.

And it does that, but then again (as I keep having to say) it does something else: it gives language, rather miraculously, a new life. Stein’s drone begins to gather overtones, until Melanctha’s story breaks the bonds of story and conventional usage to become an exploration of and a meditation on the possibilities of language, language that exists in and for, as she would come to define it in a later essay, “Composition as Explanation,” a “continuous present.”

Repetition renders Stein’s simple words and chain-link sentences surprisingly complex in effect, opening them up to multiple and shifting registers. The language of “Melanctha” can be read as Black American dialect (at least that is what a lot of Stein’s early readers took it for), and Richard Wright later told a story of reading it aloud to an illiterate Black audience who responded with immediate recognition. The language of “Melanctha” is dialect, and it is also language as it is spoken, in which we often return again and again to the same words to try to get a point across. Then again (again), the language of “Melanctha” is very much written language, an oddly unreal and quirky idiom of the printed page on which, by dint of its repetitions, it practically prints patterns (which is to say that the language of “Melanctha” is visual, too). It is also musical, echoing and chiming, and abstract and philosophical: all those reallys and certainlys and trulys reflect not only how we speak but raise the question of what we speak in the hope of, what certainty, what truth, what reality? Finally, the language is erotic, shot through with sexual innuendo—“Jeff took it straight now, and he loved it … it swelled out full inside him, and he poured it all out back”—and the rhythms (and perversity) of sex:

“But you do forgive me always, sure, Melanctha, always?” “Always and always, you be sure Jeff, and I certainly am afraid I can never stop with my forgiving, you always are going to be so bad to me, and I always going to have to be so good with my forgiving.” “Oh! Oh!” cried Jeff Campbell, laughing, “I ain’t going to be so bad for always, sure I ain’t, Melanctha, my own darling. And sure you do forgive me really, and sure you love me true and really, sure, Melanctha?” “Sure, sure, Jeff, boy, sure now and always, sure now you believe me, sure.”

Much influenced by visual artists, Stein’s work would in time prove an inspiration to such very different American composers as John Cage and Philip Glass, while “Melanctha,” shot through as it is with the rhythms of Black American speech, brings to writing something of the incantatory eroticism of the blues and soul music.

With “Melanctha,” Stein had found a way of writing that was all her own, a no-language and a new language that sounded a little bit like lots of things and like no one else. Overcoming the sense of uncertainty and inadequacy and isolation that had marked her childhood and her intellectual and sexual coming-of-age, she had fashioned an instrument that allowed her to air and explore her most characteristic and intimate concerns—her sexuality, her femininity, her philosophical turn of mind, her love of words and wordplay at once childish and sophisticated—in entire freedom and in depth.

It was her way of writing, and it was her way of being an American writer. If, as a child in America, Stein had felt hardly American, and as an adult in Europe felt at times helplessly American, on the page she was free to be her American self and, more than that—having arrived at this moment of revelation, she would have an unwavering sense of prophetic purpose—to free American literature to be itself.

She returned to The Making of Americans, and as she worked on this, her magnum opus, she also worked out a theory of the Americanness of American literature, in which the problem of scale (something Melville and James and Whitman had in various ways confronted without, however, formally defining it) became—this was Stein’s discovery—central to its promise. She develops her ideas in a lecture on English literature that she delivered in 1934. England, she said, an island nation, had naturally produced a literature marked by a delimited sense of scale, which provided a background for stories of “daily living.” English literature had been a glory in its day—Stein was steeped in it, and she paid homage to it—and it had gone through several phases, from the invention of English as a literary language in the work of Chaucer through the subsequent enlargement of its vocabulary to the muscular and mature syntax and sense of Dr. Johnson. By the nineteenth century, however, English literature had been reduced to mere phrasemaking, saying the expected thing and saying nothing much while having things both ways, a convenient accommodation of God and Mammon that you would expect from an island empire anchored in the harbor of its self-regard. Here Stein rebels against the balance of the nineteenth-century novel.

English fiction, the fiction of a closed circle, had lost its honesty and its power, just as England had lost the power to dominate a world that had begun to expand continuously and violently outward—a world that could be said to have begun with the discovery of America and that looked like America more than anything else. England had the defined shape of an island, but America had no defined shape: it was a frontier, moving, the eccentric center of a widening world, a world not of settled definitions, but of unending exploration, where everything was in question. James, in Stein’s view, had been the first American writer to catch a glimpse of this new, decentered reality, for though he had worked with an inherited English sense of the shape of the novel, he also had, in her words, “a disembodied way of disconnecting something from anything and anything from something [that] was an American one.” This accomplishment had paved the way for Stein, who not only recognized it for what it was but formalized it, isolated it, as a researcher might a strain of bacteria, and made it into a matter of conscious procedure:

I went on to what was the American thing the disconnection and I kept breaking the paragraph down, and everything down to commence again with not connecting with the daily anything and yet to really choose something.

So she characterizes her way of working in “The Gradual Making of The Making of Americans,” and she goes on from there to describe how this new way of breaking things down became a way of building things back up, and so on. The work was forever ongoing, a continuous revelation of the writer’s power not to reflect given realities in given forms, but, as Stein says, “to really choose something,” and from it emerged a vision of a new kind of wholeness born of words: “I made a paragraph,” she boasted, “so much a whole thing that it included in itself as a whole thing a whole sentence.”

And this is the key thing that Stein discovers and passes on: putting the sentence at the center of writing, a sentence that can go on and on or be cut as short as can be, but that one way or another, as a kind of exploratory probe, takes precedence over the idea of the work as a whole. You start with the sentence and the sentence finds out where it is going and you go from there. This American “disembodied way of disconnecting something from anything” goes on finding its own path across the page: “Then at the same time is the question of time. The assembling of a thing to make a whole thing and each one of those whole things is one of a series.”

She concludes: “I felt this thing, I am an American and I felt this thing, and I made a continuous effort to create this thing … a space of time that is filled always filled with moving.”

From Stranger than Fiction: Lives of the Twentieth Century Novel, to be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux this November.

Edwin Frank is the editorial director of New York Review Books and the founder of the NYRB Classics series. He has been a Wallace Stegner Fellow and a Lannan Fellow and is a member of the New York Institute for the Humanities, a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, and a recipient of a lifetime award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters for distinguished service to the arts. He is the author of Snake Train: Poems 1984–2013.

Nor can I say for sure when clear Plexiglas allows a cloudy look at the surface and when Paiement continues to paint over the Plexiglas. Nature and handiwork come together.

Nor can I say for sure when clear Plexiglas allows a cloudy look at the surface and when Paiement continues to paint over the Plexiglas. Nature and handiwork come together.