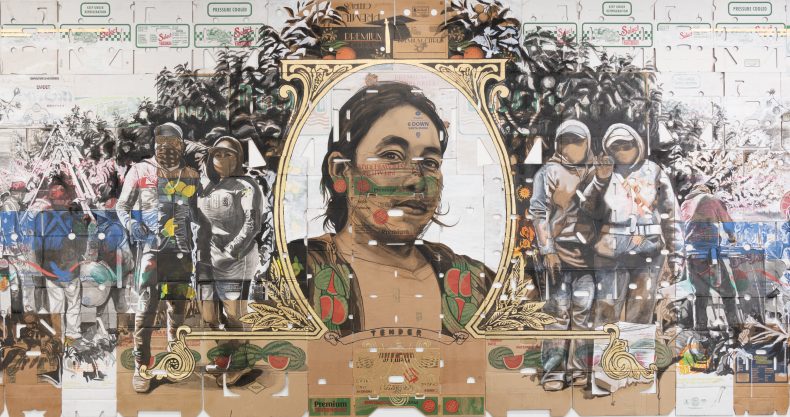

Sam McKinniss, Star Spangled Banner (Whitney), 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

1. The Divine Celebrity

“There isn’t really anybody who occupies the lens to the extent that Lindsay Lohan does,” the artist Richard Phillips observed in 2012. “Something happens when she steps in front of the camera … She is very aware of the way that an icon is constructed, and that’s something that is unique.” Phillips, who has long used famous people as his muses, was promoting a new short film he had made with the then-twenty-five-year-old actress. Standing in a fulgid ocean in a silvery-white bathing suit, her eyeliner and false lashes dark as a depressive mood, she is meant to look healthily Californian, but her beauty is a little rumpled, and even in close-up she cannot quite meet the camera’s gaze. The impression left by Lindsay Lohan (2011), Phillips’s film, is that of an artist’s model who is incapable of behaving like one, having been cursed with the roiling interior life of a consummate actress. Most traditional print models can successfully empty out their eyes for fashion films and photoshoots, easily signifying nothing, but Lohan looks fearful, guarded, as if somewhere just beyond the camera she can see the terrible future. Unlike her heroine Marilyn Monroe, Phillips also observed in a promotional interview, Lohan is “still alive, and she’s more powerful than ever.” It is interesting that he felt the need to specify that Lohan had not died, although ultimately his assertion of her power is difficult to deny based on the evidence of Lindsay Lohan, which may not exude the surfer-y, gilded vibe he might have hoped for, but which does act as a poignant document of Lohan’s skill, her raw and uncomfortable magnetism.

“Lindsay has an incredible emotional and physical presence on screen that holds an existential vulnerability,” Phillips argued in his artist’s statement, “while harnessing the power of the transcendental—the moment in transition. She is able to connect with us past all of our memory and projection, expressing our own inner eminence.” “Our own inner eminence” is an odd, not entirely meaningful phrase, used in a typically unmeaningful and art-speak-riddled press release. What the artist seems to say or to imply, however, is that Lohan’s obvious ability to reach inside herself and then—without dialogue—vividly suggest her depths onscreen acts as a piquant reminder of our own complexity, the way each of us is a celebrity in the melodrama of our lives.

What makes Lindsay Lohan art and not a perfume advertisement, aside from the absence of a perfume bottle? The same quality, perhaps, that makes—or made—Lohan herself a star, as well as, once, a sterling actress. All Phillips’s talk of transcendence and the existential may be overblown, but then stars tend to be overblown, as evidenced by the superlatives so often used in descriptions of Hollywood and its denizens: “silver screen,” “golden age,” “legendary,” or “iconic.” “Muses must possess two qualities,” the dance critic Arlene Croce claimed in The New Yorker in 1996, “beauty and mystery, and of the two, mystery is the greater.” At first blush, Lohan might not have seemed like an especially mysterious muse, with her personal life splashed across the tabloids and her upskirt shots all over Google. In fact, her revelations are a trick, the illusion of intimacy possible because she has enough to plumb that we can barely touch the surface. We can see her pubis and her mugshots and the powder in her nostrils, but it is impossible for us, as regular, unfamous people, to know what it feels like to be her.

“When [Lohan] bats her eyes over the Gagosian Gallery logo at the end of Phillips’s short film, millions of art world dollars immediately alight upon our shores,” the late and cantankerous art critic Charlie Finch wrote in a review of Lindsay Lohan, later noting that the film also acts as a salute to “the cosmetology industry as treated cosmologically.” “Few beauties have (ahem) not required the surgeon’s knife as little as Lindsay,” Finch continues, “but her lips sure appear to be as (allegedly) collagen-injected as those of Melanie Griffith, Meg Ryan, or Cher. Score another point for Richard Phillips, patron saint of female models everywhere and their cutting-edge search for visual perfection.” It was certainly permissible to write about a female subject in a rather different tone in 2011, and the titillated focus on cosmetic surgery here now feels quaint. Still, whether or not Finch is being facetious, he is right about Phillips’s willingness to lavish his attention on the hard work stars do to keep themselves suitably celestial, ensuring prominent places in the firmament of fame.

In the same year, Phillips mounted a show at London’s White Cube that featured portraits of a host of other desirable famous people, including Zac Efron, Robert Pattinson, and Miley Cyrus, all of whom the gallery’s write-up described as “secular deities.” In each image, Phillips carefully renders a wallpaper-style repeated pattern of a high-end designer monogram—for instance, the Louis Vuitton “LV”—behind his subjects, meant to replicate what are known in the trade as “step and repeat” backdrops from red carpets, but also intended to highlight the astronomical and enviable value of the figures he depicts. The works, which he called a comment on “the marketability of our wishes, identity, politics, sexuality and mortality,” are not necessarily anti-celebrity, and in fact the flatness and the faux naïveté of Phillips’s brushwork lends them the impression of a brilliantly executed bit of fan art.

Actors and actresses are often rumored to be smaller than the average person, maybe because of the adage that the camera adds ten pounds, or maybe because they are increased to a Godlike scale regardless when they are projected on a screen, making their real size more or less irrelevant. Certainly, there is no other quality that magnifies an individual like charisma, helping to explain why we continue to be shocked to learn that, say, Marlon Brando was a little under five foot nine. Phillips’s canvases, which render what are in effect premiere headshots at about ten times the size of actual life, perform the same alchemy the cinema screen does, minus the narrative and the individuating sheen of cinematography. They show Chace Crawford or Leonardo DiCaprio for what they really are: supersized, halfway between a spokesmodel and a god, as inseparable from commerce as a Louis Vuitton handbag. Asking what differentiates Lindsay Lohan from a perfume advertisement, aside from the lack of purchasable perfume, is, in other words, redundant: Lohan may be hard to understand or to completely tame, but she was still at one time a big seller, and just like an artwork her intrinsic value is and always has been subject to trends, market fluctuations, her ability to look good in a well-appointed room. Disappointingly sublunary, to think that a star might be no more than a product—but then it is equally depressing to think that the same is true of a supposed artwork.

2. The Decaying Celebrity

In 1974, in Florence, a Californian hippy couple were visiting the Uffizi when a strange thing happened to the heavily pregnant wife: as she stood admiring a da Vinci, she began to feel her baby moving, as if he too had been struck by the genius of the work. “Allegedly, I started kicking furiously,” Leonardo DiCaprio told an interviewer at NPR in 2014. “My father took that as a sign, and I suppose DiCaprio wasn’t that far from da Vinci. And so, my dad, being the artist that he is, said, ‘That’s our boy’s name.’ ” That I first encountered this origin story as a child at the height of Leo-mania in the nineties, in an unofficial souvenir book about the then-twenty-one-year-old actor and heartthrob, feels entirely apposite: it is a clever bit of mythmaking, an anecdote that might just as well have belonged to classic Hollywood and the era of Photoplay or Screenland as to the first, faltering days of the online age. DiCaprio’s father, an underground comics publisher who associated with both Timothy Leary and the graphic artist and world-renowned macrophiliac Robert Crumb, foresaw Leonardo’s future status as an artist even if he was not certain of the medium he would work in. Many of us who were prepubescent when Leonardo DiCaprio first rose to real prominence are eminently aware of his nineties image as the ultimate nonthreatening (very nearly nonsexual) sex symbol, so rosy-faced and champagne-haired and softly pretty that that he might as well have been a handsome girl, but the ardor of his swooning fanbase did not cancel out his reputation in adult critical circles as a genuine early master of his craft. Consider the cool, casual way he delivered Shakespeare in Romeo + Juliet (1996), Baz Luhrmann’s loony, technicolor adaptation of the play: young, alive, unmistakably Californian, he spoke all his thee’s and thou’s with the throwaway inflection of a person fluently communicating in a second language they had practiced all their lives.

As it happened, DiCaprio ended up with a more literal link to art in later life, becoming a collector of such scale and (to use Phillips’s word) eminence that, in spite of his being a supposedly frivolous Hollywood A-lister, the art world takes him fairly seriously. Unlike, say, collecting classic cars or couture clothing, the maintenance of an art collection has the dual benefit, for a celebrity, of conferring cultural cachet and trumpeting their tremendous wealth (provided, of course, that their selections knowingly and tastefully run the gamut from aesthetically desirable to conceptually rigorous, haute-contemporary to historical). DiCaprio—who does not seem to have an art buyer in his employ, and who therefore presumably actually cares about the pieces he acquires—is catholic in his tastes, collecting works by artists like Basquiat and Picasso as well as other, much newer works by relative unknowns.

It may be the comprehensive breadth of his collection that has led to his being courted, then immortalized, by more than one prominent artist. Elizabeth Peyton has painted him twice—the first work, Swan, was produced based on a photograph by David LaChapelle in 1998, and the second, Leonardo, was created after DiCaprio sat for her in 2013. In Swan, the actor is at the vertiginous height of his babyish loveliness, and he is depicted with a swan’s neck draped around his shoulders, ruby-lipped and pouting, his eyes bluer than any human being’s and his skin as pale and as bloodless as a vampire’s. In Leonardo, he looks stolid and serious, his flat cap pulled down to hide a little of his famous face. There is an evident difference in the style of both these works: Swan is more abstracted, closer to a fantasy than to a fact, and Leonardo has a detailed intimacy that makes it more recognizably an image of its subject. In addition to the maturation of the painter, it is reasonable to imagine that her first portrayal of DiCaprio, especially because it has been drawn from a heavily stylized fashion image, has more to do with how she imagined him at a great, awestruck distance in the nineties, and the second is a more accurate and less starry record of what it is really like to meet one’s hero, i.e., sometimes not as glamorous as one might think.

In her list of the top ten cultural objects of the year for Artforum in 1999, Peyton cited Leonardo DiCaprio’s brief appearance in the 1998 Woody Allen film Celebrity as an artistic highlight. Playing a young A-list actor with the generic, haute-American name Brandon Darrow, DiCaprio is required to stand in for all of Hollywood’s excesses, and he does so with aplomb, strutting through an Atlantic City casino and snorting cocaine off the back of his delicate hand with such assurance and such grace that it is easy to see why he was a phenomenon in the late nineties. His cameo is “ten electrifying minutes of seeing Leonardo be what he really is,” Peyton rhapsodized. “Usually we have to see him being nice and innocent. Here he is a huuuuge star: powerful, arrogant, and beautiful.” That combination of power and beauty is what the painter aims to capture in her subject in Swan, and the cruel and foppish pursing of his lips suggests a little arrogance too. Although Peyton has reproduced her young DiCaprio from an editorial photograph, her choice to use the image with a swan may be a subtle nod to Zeus, who in Greek myth disguised himself as one in order to fuck Leda, as if he were a celebrity disguising himself to hook up with an unfamous fan.

In 2019—by which time he was very powerful indeed, even if he was also significantly less beautiful—DiCaprio commissioned the Swiss artist Urs Fischer to produce a portrait of his family, presumably hoping to usher his art-appreciating mother and father into the annals of art history in much the same way he himself had been immortalized in those earlier works by Peyton. Fischer chose to render the DiCaprio family at a larger-than-life scale, not in paint or marble but in wax, as part of an ongoing series of candle works. The piece, titled Leo (George & Irmelin), shows two melded Leonardos, one being embraced by his mother, Irmelin, and one apparently engaged in conversation with his father, George, in a setup meant to reference the son’s status as the child of separated parents. The figures, brilliant white with light pink and baby blue touches, are designed to melt into liquid once the wicks that emerge from their four respective heads are lit, and inside they are pitch-black, making the piece a rather bleak portrayal of a shattered family unit.

Looking from Elizabeth Peyton’s Swan to her later Leonardo, it is possible to see a record of another kind of dissolution, from the smooth and stainless early Leo to the older, less cherubic incarnation, a transformation that seemed to happen at DiCaprio’s behest as he eschewed stylists and personal trainers in his off-set downtime—a destruction of his ultrasaleable and almost feminine cuteness in favor of a more crumpled human guise, not overexercised or neatly shaven or attired in designer clothing but more versatile, more real. Paradoxically, in spite of his profile as a Hollywood actor never having been more serious or more prominent, in Leonardo and in Leo (George & Irmelin), his image is not necessarily that of a “huuuuge star,” but of something closer to the thing he “really is”: a very famous middle-aged man who has been touched by time in more or less the same way as an average and unfamous one, his youthful luminousness having melted like pale wax. The writer Osbert Sitwell once observed that those who sat for portraits by John Singer Sargent looked at the results and “understood, at last, how rich they were.” One wonders if DiCaprio looked at Urs Fischer’s rendering of him as a thing of obvious impermanence, a fleeting source of light, and finally understood that no amount of wealth would stave off death, however many twenty-four-year-olds he slept with.

3. The Martyred Celebrity

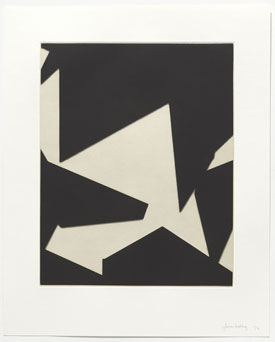

In 2017, the painter Sam McKinniss produced a portrait of the late Whitney Houston entitled Star Spangled Banner, based on a shot from Houston’s transcendent performance of the American national anthem at the Super Bowl in 1991. The piece is a spotless invocation of the blend of tragedy and majesty that now characterizes Houston’s story. She is framed in close-up, her lips parted either in preparedness to sing or in the aftermath of having unleashed her soaring, immaculate voice, flawless as crystal, and the fact we cannot tell which of these moments is depicted hardly matters—all that does is that this face, this mouth, is the place from which once emanated something of such holy beauty that it’s easy to imagine Houston feeling heavy with the knowledge of her staggering ability, so that the sheen on her skin might signify exertion, but might also indicate that she is nervous.

Interestingly, Houston’s version of the anthem was not live, but prerecorded: in the video McKinniss uses as a reference, she is singing, but into a dead mic, making the performance itself a constructed simulacrum of the experience of seeing Whitney Houston sing, and the painting of this moment an effective simulacrum of that simulacrum. Watching the clip, it is easy to slip into the belief that what we’re seeing is reality, and that there is no space between the ecstatic vocal we are hearing and the one emerging from her body. This is perhaps the quality that makes a good celebrity, and makes good art, and makes good art about celebrities: it’s magic, the ability to cast a spell or an illusion without letting the one being hypnotized know that they’re being fooled.

McKinniss has often maintained that he paints swans because swans are, in their own way, celebrities, reasoning that their long affiliation with romance makes them so soppily familiar, and so loved, that they might as well be A-listers in their own right. It is this sentimentality, I think, which gives Star Spangled Banner its almost inexplicable power. How does one explain the presence of a feeling in a painting? The easiest thing to point to is the source material, which has been carefully selected to show Houston in a moment of potential and personal triumph; less easy to point to is the exact method with which McKinniss manages to capture the glimmer of vulnerability in her eyes, the wonder in the slackness of her mouth.

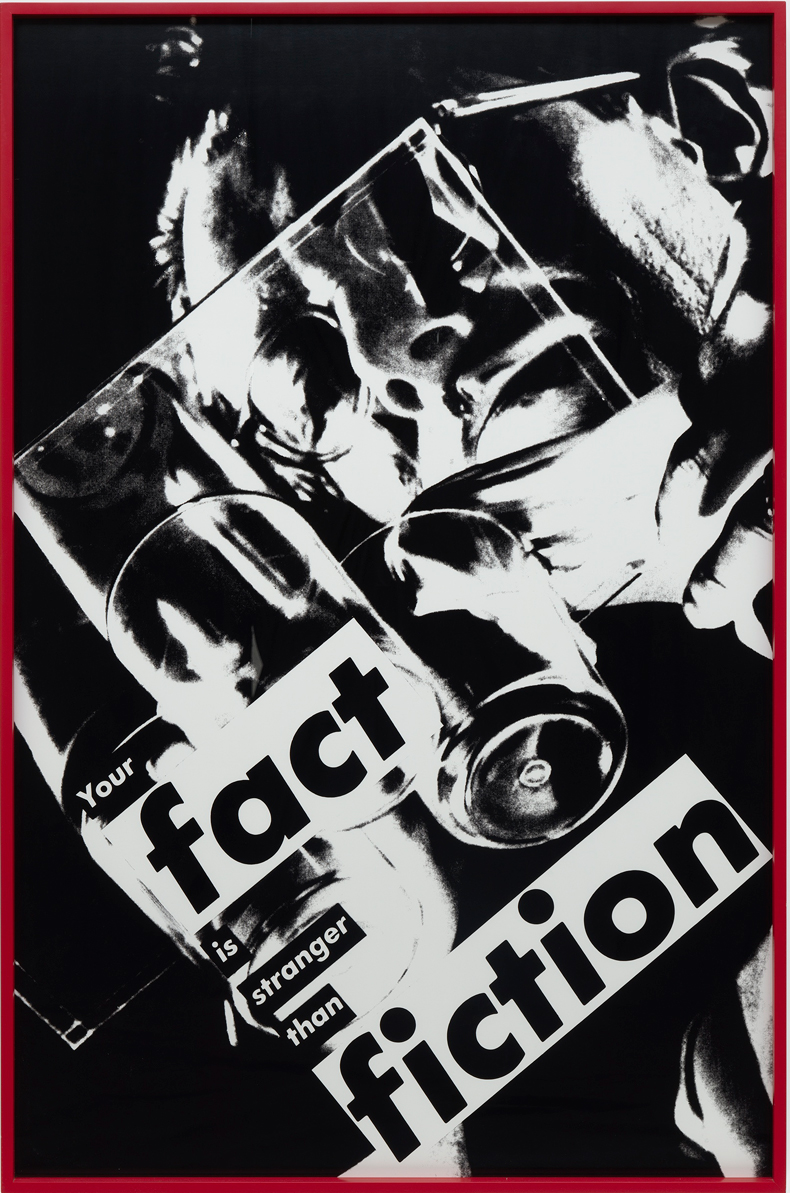

McKinniss’s painting brings to mind another artwork about an extremely famous, abundantly talented woman who met an untimely, tragic end—namely, Andy Warhol’s fading silkscreen of Marilyn Monroe, her tight smile and slender, embowed brows replicated and then ghosted, faintly, into nothing, into death. Painted in 1962, the year Monroe died from a barbiturate overdose, Marilyn Diptych is based on a publicity still from the Henry Hathaway 1953 film Niagara, and as with McKinniss’s choice of source material for his Whitney Houston painting, the decision to use this particular shot is charged. In Niagara, Marilyn plays a beautiful adulteress named Rose who, like Marilyn, is doomed, more or less from the film’s first frame, by her sexuality. She is hoping to abandon her jealous and violent husband, George, in favor of a lover who will keep her in the forefront of his mind like an especially catchy love song. Like Marilyn’s own second husband, the baseball player Joe DiMaggio, George has captured and attempted to domesticate a femme fatale, and cannot understand why marriage has not been enough to curb her appetite—the addition of a diamond to her finger not, as it turns out, being equal to a neutering or a lobotomy. Murder, as is often the case for a man like this, is decided on as the appropriate solution. When advertisements for Hathaway’s film boasted that it contained “the longest walk in cinematic history”—the walk being Marilyn’s undulating sway, captured on 116 unbroken feet of celluloid—they failed to mention that this walk was her character’s attempt to escape death. (Her imminent demise, of course, was what made the exercise so piquant and so titillating, whether or not audiences wanted to admit it to themselves.)

In taking Marilyn Monroe as she appeared circa Niagara—her first true lead, and a role that would help calcify her reputation as a woman who was just too hot to be allowed to live—Warhol forces us to rewind to the first reel of the picture, showing her vividly rendered in yolk yellow and rose pink, a slash of cerulean blue over her eyes, and then repeats the image until minor variations become clear. Marilyn’s career, too, was quite often a series of repeated images with minor variations, her astounding comic talent and nearly untapped ability to render delicate and trembling emotion typically forced into the unyielding shape of sexy airheads, gold-diggers, and girls with no aspirations outside marrying rich.

In the diptych’s second half, the same picture reappears in black and white, and rather than subtle dissimilitude, each new version is marked by an obvious degradation, as if it has been eroded or destroyed. A dark smudge, like a grave contusion, runs vertically through one column, and another is so highly contrasted that very little remains of the subject other than her most essential features, showing Marilyn Monroe as she might be spoofed in a newspaper cartoon, or used to advertise a beauty product.

“You’re a killer of art,” Willem de Kooning once supposedly slurred drunkenly at Andy Warhol at a party, making a familiar accusation before doubling down with something slightly different: “You’re a killer of beauty.” If the former is debatable, the latter is a curious accusation to level at a man most famous for loving surfaces, perfection, plastic. It is, though, an accurate reading of Marilyn Diptych, a work that is fundamentally about the public’s ravenous consumption of, and then destruction of, the beauty of an actress who was given little opportunity to prove what else she could provide. You’re a killer of beauty, the repeated, fading faces seem to say to those who look at them, the work’s tone far closer to that of the pieces that make up Warhol’s Death and Disaster series than that of his more conventional Hollywood portraits. Marilyn Diptych is Marilyn Monroe as a car wreck; as a jet crash; as a desolate electric chair. Like McKinniss’s Star Spangled Banner, it succeeds in its determination to depict something essential of its subject, making visible to the naked eye what we might previously only have been able to experience with the gut or the heart. Unlike McKinniss’s painting, what it communicates is not the radiance or the talent of the woman at its center, but the obverse: the insidious and unstoppable leeching of those qualities by an unfeeling industry, a media with a thirst for tragedy and a slavering audience, until what remains is so faint we can no longer perceive it as the image of a woman at all.

From Trophy Lives: On the Celebrity as an Art Object, out from MACK Books this month.

Philippa Snow is a critic and essayist. Her work has appeared in publications including Bookforum, Artforum, The Los Angeles Review of Books, ArtReview, Frieze, The White Review, Vogue, The Nation, The New Statesman, and The New Republic.