The Paris Review – Hands

[ad_1]

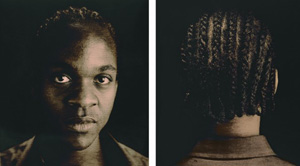

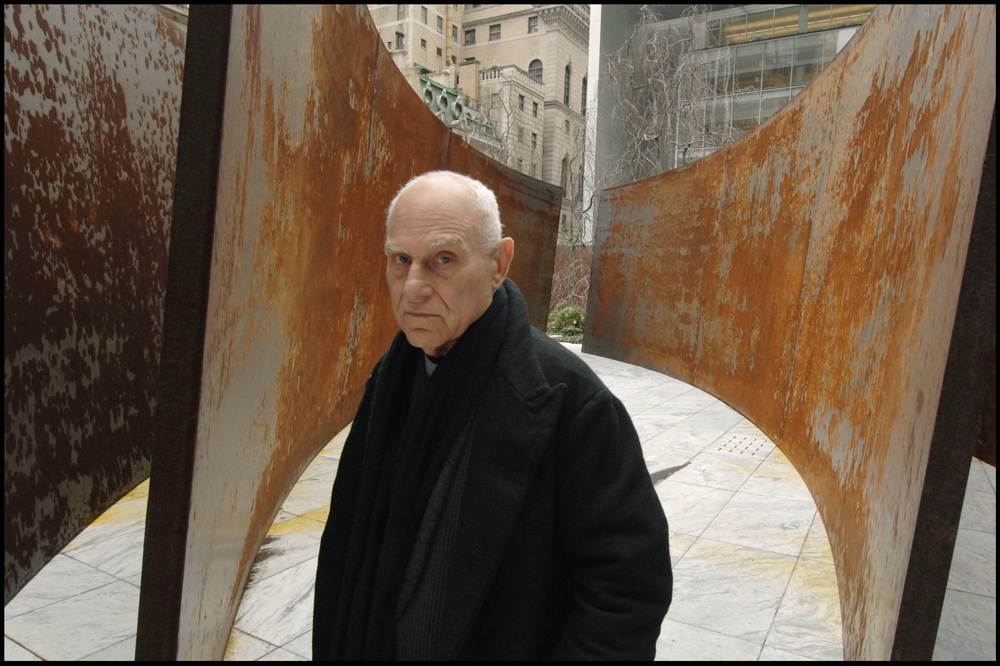

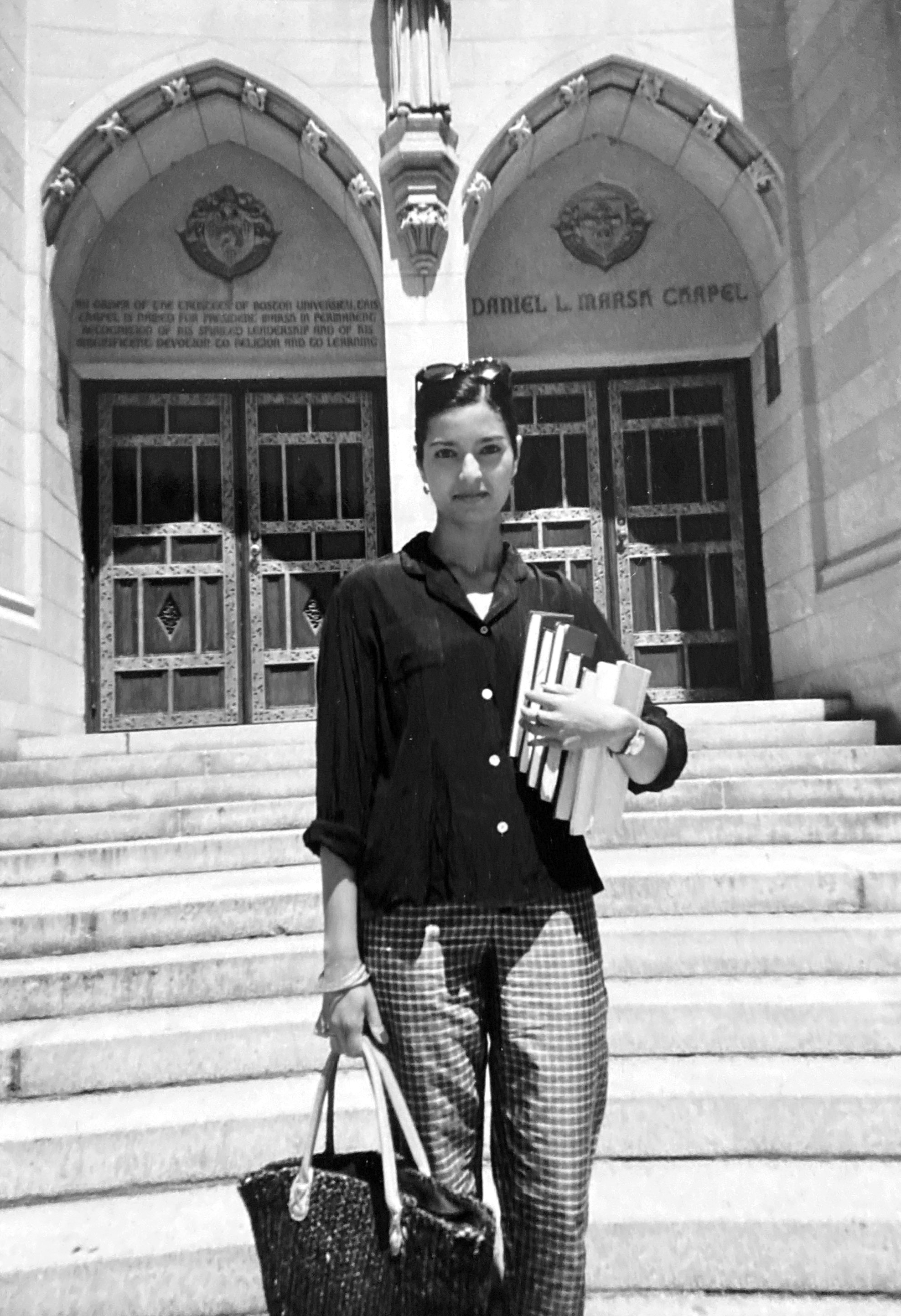

Photograph by Edna Winti. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY 2.0 Deed.

I am prepared. I have had my will drawn and notarized. I’ve given away old books from my library that I will never read again. I’ve gotten rid of porno magazines and cock rings, things that would be difficult or compromising for my beloved to discard. Mother has all my baby pictures I stole. I have paid for my cremation. I carry a pocket full of change to give to panhandlers. My elementary catechism has returned; those who help the lowliest …

Marcus says he just doesn’t understand me sometimes, says he has dreams for us, a home we will build together, but it seems to him I’m giving parts of my life away. I sit quietly at the deli booth, staring at my unfinished sandwich. It is rare now for me to be hungry; the bones in my face have become more distinct. It is when I don’t respond that he gets annoyed, but I can’t help it. I don’t want to change his feelings or argue the probabilities. I don’t believe I have long; my blood has turned against me, there is no one here to heal me. The sunlight from the window pours heavily onto his face, rugged and aged. Myself, I have to stay away from the sun; my face discolors from all the medications I take.

Marcus has become quiet, maybe brooding. I hear a knock on the window next to me. It is a tall man, very dark and in a ragged black suit. He points with a dirty finger at the tray that holds my half-eaten sandwich, then brings his fingers to his mouth. I nod my head. Marcus hates when I do stuff like that, and he barks, “Why’d you do that? Why can’t you just save it for later?”

The man comes to our table, pulls the tray closer to him, unwraps the sandwich from the paper. Marcus leans back far away. The man is intimidating, his form towers over us. I want to tell him to take it away, but he just stands there and eats. Finally, Marcus says, “There’s an empty table over there!” The man gives thanks and then asks for the rest of my drink, which I refuse because I know it would piss Marcus off since he bought lunch. Marcus and I are silent for the rest of his lunch break.

It has become a ritual of sorts, to have lunch on Thursday with Marcus at his work. Sometimes I am too early, or I can see that he is busy with a client. The nursery is very dense and serene, and as he walks through it, he is in total command, like a god in his Eden. The customers are rapt at his every word on how to take care of the plant, what it is suited for, what it will look like in a year, two years. This is one of the reasons I love him, his ability to nurture. It is like he knows the secrets of life and wants to share them with me. I don’t want to be seen at his work.

This is a way I show him my love. My face looks too haggard. I have strange discolorations on my forehead and chest. I look as if I am going to die soon. I don’t want any rumors started about Marcus and me at his work. I don’t want him having to answer difficult questions about his friend. I can imagine his soiled hands clenching.

When I am early, or he’s busy, I go sit at this small Catholic church across the street. The parking lot is usually empty and there’s a porch by the rectory, which I go sit on. The Father has looked at me before through his window and knows that I am just there to wait.

Often when I am there, a large Mexican woman comes by. She carries paper bags from Pic ’n’ Save. Over the brims of the bags, plastic-and-silk flowers stick out. Some weeks they are all blue, others purple, still others pink and red. The woman has taken to nodding at me, “Como ’sta?”

One day, with a smile on my face, I said, “Merci.” She gave me a look and then I knew I’d made a mistake. “Bien, bien, señora!”

She laughed and said, “Ay.”

French has always come easier to me. I’m sure she thinks I’m some sort of pocho, like an Oreo, brown on the outside, white on the inside.

The large woman usually wears something that my grandmother would wear, a kind of flowery smock so she won’t get dirty. She decorates the statue of Mary that stands in the corner of the parking lot, under a large, sturdy eucalyptus tree. On holidays, she’s put out plastic jack-o’-lanterns, Styrofoam snowmen at Mary’s feet, and always lots and lots of fake flowers. Marcus has often told me that he’d give me some perennials, other flowering plants to give to the woman, but I think she wouldn’t want them. I think she loves the fake flowers’ everlasting quality. She does it as a devotion, and when she finishes, she prays, her knees on the cement, her head bowed down, hands pressed together. I’ve told Marcus it is like she has her own form of serenity, that she sees beauty over life, or that she sees her actions as more important than presenting living things.

The most notable thing about the Mary statue is that she has no hands.

Being at the rectory alone makes me think of death. Would I do it to myself if I got really ill? What if I start losing my mind? What if I start looking like more of a freak than I already do and people start staring? What if it becomes too painful for Marcus to be with me?

My upbringing haunts me, like a shadow of the tree. I was taught that I could never go to heaven if I killed myself, that even the most ill cannot do that, because life is a gift we must fully use or otherwise appear ungrateful. My archbishop taught me that. My parents had set up those meetings with Archbishop Mahoney because they didn’t know what to do with me, and they were afraid a doctor would lock me up in an institution. When I was twelve, I had already tried pills I got at school and from my father’s medicine cabinet. The paramedic who revived me cried openly, said he’d never seen a young boy try such a thing. Worse yet, my parents were horrified when they came out to the garage and saw lit stacks of newspaper, soaked with lighter fluid, surrounding me. Parts of my arms and legs were burned severely and today I carry those scars. No one ever understood why I would become so quiet, disappear into my parents’ closet for hours in the dark. Sometimes I would torture my pets, make the other children on our block cry. Still the only feeling I have now is guilt, and when I think of myself, I think I’ve wasted my life. All I remember fully though is a sound, the rush of air igniting.

I figure the hands of Mary must have broken off during an earthquake, or maybe due to vandals. There’s a bronze plaque that reads, “I have no hands but yours.”

The day I read that, the Mexican woman had come up behind me quietly and placed her hand on my shoulder. She started speaking Spanish much too quickly for me to understand. When she figured out I didn’t speak Spanish well enough, she switched over to a slow English. “My name es Yoli, Yolanda.”

It was my turn to say, “Como ’sta?”

There was a gentleness in her voice. “I see you here all the time?” I told her I was waiting for a friend. “Oh, you can help me though?” She pulled out a small hand rake and said, “Weeds.”

I got on my knees with a chuckle and started raking out the weeds that had grown in the flower bed. Eventually, my hands began to ache from the exertion. It was very quiet work.

She changed the vases and put blue flowers and then some calla lilies in the glass containers. I told her how Marcus worked at the nursery across the street and said that I could give her some flowers and other plants if she wanted. I told her maybe some small ivy around the edges would be nice. She smiled and said, “Gracias.”

I started to notice the meditative quality of working this soil, how there was something like a warm charge I received from the earth, that I became more spirit than being. And like the wind flittering through the eucalyptus tree, it felt like she was speaking to me telepathically.

“My son used to do this every Thursday, before I took over.” I stopped what I was doing. “He loved real plants, fussed over this small garden. The Father mentioned often how devoted Tulio was, how his love was an example to all of us. I was so proud of him.” On Yoli’s face, I saw a pride I wished my own parents could give me. “The women of the church would surround me and praise me for raising such a fine young man. But nobody saw how lonely he was. How he would drink in my kitchen till he passed out crying, ‘Mama, Mama.’ ”

I turned back to my work, flustered because I knew how he needed to create beauty in his life. “When the earthquake came,” she said, “and the hands of Mary broke, he wanted the church to have it fixed, but Father said, ‘No, it is more symbolic this way.’ Tulio could not understand; it was like the Mother of God was a real person to him and needed to be healed.”

I huffed, thinking of my own life. She turned her face away from me. “Everyone was surprised that day. I wasn’t. They came to my house, the Father, women of the church. I could tell they had been crying. They said, ‘Yoli, don’t cry but you have to see your son, you have to come with us.’ Tulio had said he was going to trim down the tree over Mary, that the boughs were too low, so off he’d gone with the ladder and some rope.”

The shade of the tree covered us both as she spoke. “Mary stands so far away from the street no one noticed Tulio stringing up the rope, pushing himself off the ladder. When I saw him, it seemed the air gently rocked him back and forth, his feet nearly touched the head of Mary. It was many days before I cried. Somehow, I knew it was all my fault.”

I wanted to ask her why, but I knew. Tulio saw no life ahead, and simply creating these altars was not enough. He was a man who wanted to heal and to be healed.

Marcus came at that moment, asked me to see a ficus tree he wanted to bring home. All I could say to Yoli was, “I’m sorry, so sorry.” Marcus was proud of the ficus he had picked for me; it looked sturdy, the roots unbound. Near the trees were shelves with pots and ceramic figures of cherubs and gargoyles. I noticed that a few of the cherubs’ arms were broken, parts of the wings missing. I could see myself grinding the arms down just to the hands and I started contemplating whether I should use glue or plaster, maybe cement.

I couldn’t tell if it was an act of creation or violence against the church. Maybe both. In my mind I saw what Tulio must have looked like. His smile must have been dazzling.

I picked up the broken arm and asked Marcus if I could possibly have this and another hand. Marcus shrugged his shoulders, questioned me, Do I want the tree or what? I kissed him lightly on the mouth, surrounded by the lushness of the nursery. He looked embarrassed in his paradise.

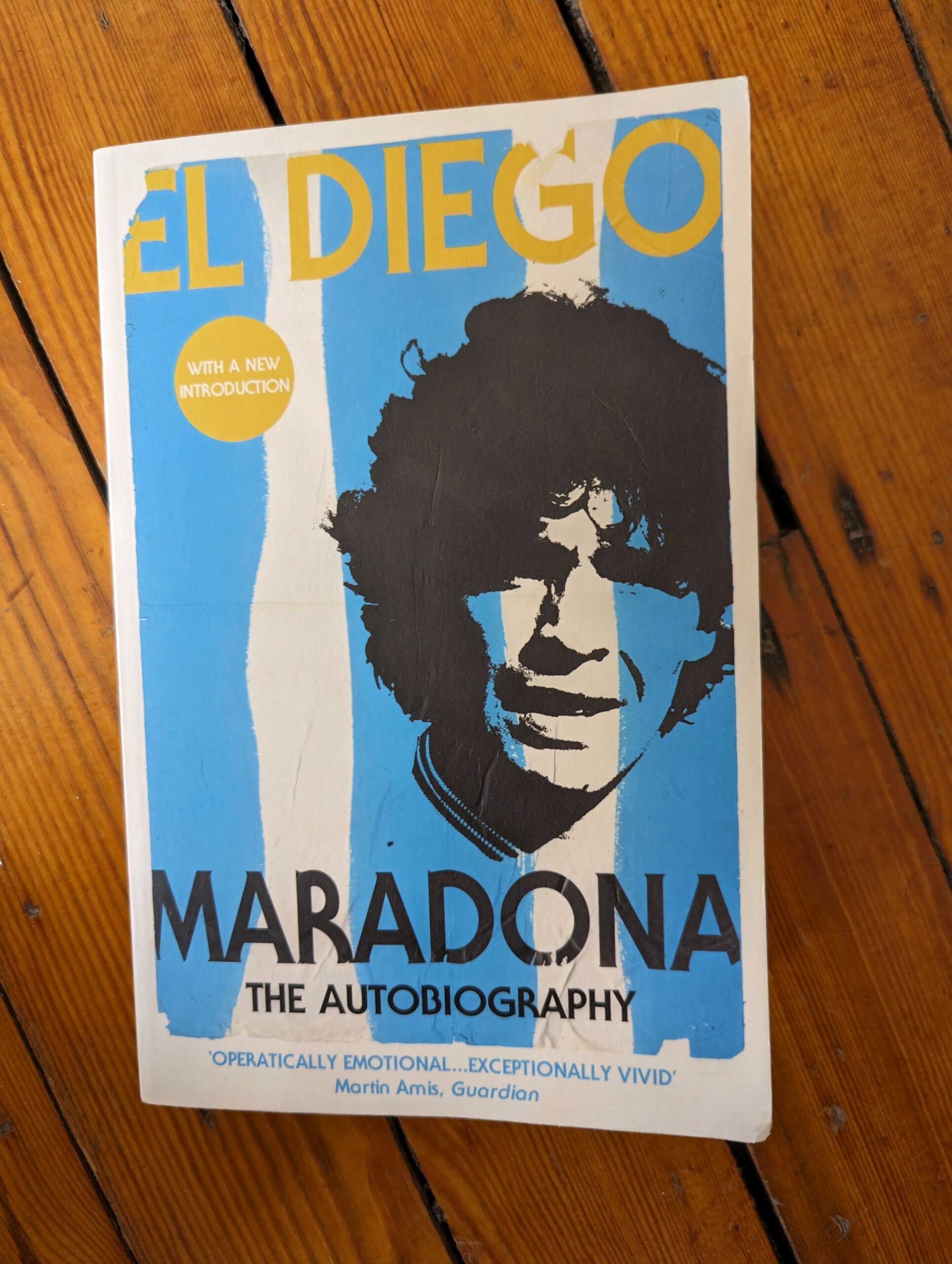

Gil Cuadros (1962–1996) was diagnosed as HIV positive in 1987 and channeled his experiences into the acclaimed collection City of God, published by City Lights in 1994. “Hands” is excerpted from My Body Is Paper: Stories and Poems, a previously unpublished body of work forthcoming from City Lights in June.

[ad_2]

Source link