Acquisitions of the month: October 2024

[ad_1]

Clark Art Institute, Williamstown

Works from the Tavitian collection by Van Eyck, Rubens, Bernini, Vigée Le Brun and others, and a $45m donation

In a transformative donation, the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, has received a gift from the Aso O. Tavitian Foundation of 331 works of art, as well as more than $45m to fund the construction of a new museum wing and a new curator in early modern European painting and sculpture. The art comes from the personal collection of Aso Tavitian (1940–2020), a Bulgarian-born businessman and philanthropist who made his fortune in the software industry and was an avid art collector, amassing some 1,200 works. The donation includes an exceptional collection of Old Master paintings by artists including Watteau, Rubens, Van Eyck, Angelica Kauffman and Jacques-Louis David, as well as sculptures ranging from a bronze by Bernini and a bust of Nicolas Poussin by François du Quesnoy (both made in the 1630s) to a group of 18th- and 19th-century French plaster and marble figures by Jean-Antoine Houdon, Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux and Gustave Crauk, among others. The Clark already has a strong collection of early modern European painting, but fewer sculptures – a gap that this acquisition will help to fill. Tavitian was a longtime friend of the Clark, serving on its board of trustees between 2006 and 2012. The new wing, which will display the gifted collection in its entirety when it opens, will be named after him.

Madonna of the Fountain (c.1440), Jan van Eyck and workshop. Clark Art Institute, Williamstown

Het Noordbrabants Museum, ’s-Hertogenbosch

Head of a Woman (Gordina de Groot) (1885), Vincent van Gogh

Het Noordbrabants Museum in ’s-Hertogenbosch has acquired Van Gogh’s Head of a Woman (Gordina de Groot) (1885) for €8.6m, making it one of the most expensive works by Van Gogh ever bought by a museum. The work, a rough oil painting of the face of a peasant woman named Gordina de Groot (who is one of the models in his Potato Eaters, produced in the same year), had been in the personal collection of the London-based collector and dealer Daniel Katz, who bought it at a Christie’s sale in February 2023. After he did so, the Noordbrabants solicited Katz to part ways with the painting, whereupon he agreed to loan it; the work went on view at the Noordbrabants in January. Now, after a dogged fundraising campaign to save what it calls ‘the Mona Lisa of Brabant’, the museum has purchased the painting permanently, thanks to large donations by the Dutch central government purchase fund, the Mondriaan Fund and Vereniging Rembrandt (an association of art patrons), as well as smaller donations by some 3,000 individuals. The acquisition marks a major step in the Noordbrabants’s project to strengthen its collection of works by Van Gogh, who was born and raised in Zundert, North Brabant, and who painted Head of a Woman while living in Nuenen, some 35 kilometres from the museum.

Head of a Woman (Gordina de Groot) (1885), Vincent Van Gogh. Het Noordbrabants Museum, ’s-Hertogenbosch

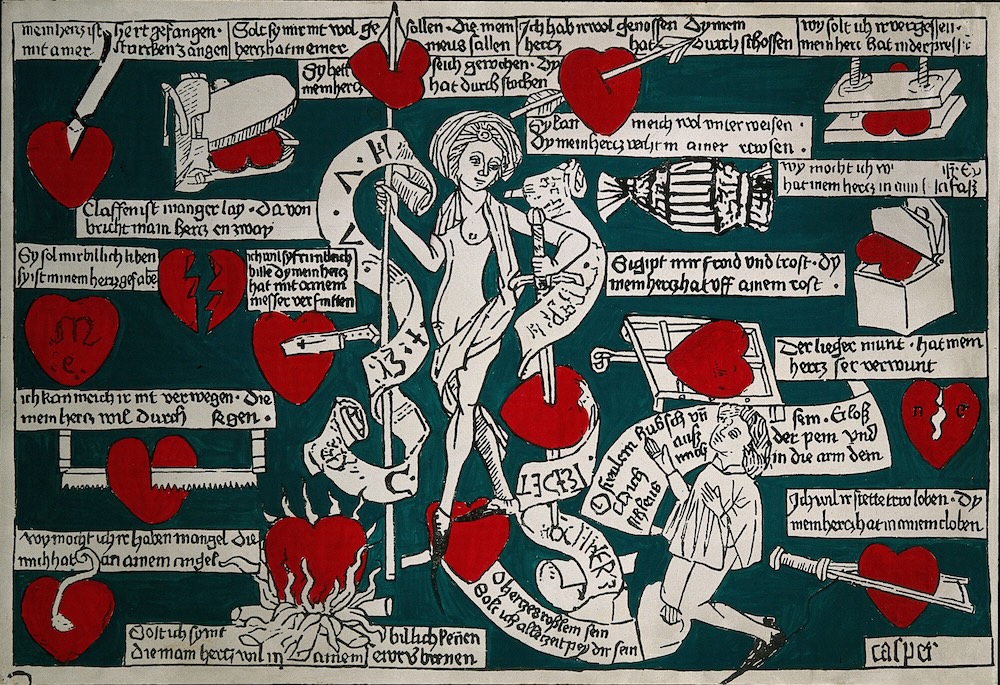

Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

The Procession of Giants in Brussels on 31 May 1615 (1616), David Noveliers

Every year in Brussels in the medieval period, a pageant called an Ommegang took place, organised by the crossbowmen guild and consisting of processions and other festivities. The Ommegang of 1615 was a notable one, buoyed by a remarkable event that took place on 15 May. During the annual archery competition that formed part of the Ommegang, the daughter of King Philip II of Spain, Isabella Clara Eugenia, who ruled the southern Netherlands as Sovereign Princess, shot down the wooden parrot that was perched atop the Church of Our Lady of the Sablon with her crossbow. To mark the feat, Isabella and her husband, Archduke Albert of Austria, commissioned eight paintings of the Ommegang celebrations by noted court artists of the time, six of which have survived. The Prado, which already owns three of these works (all by Denijs van Alsloot), has now added another to its collection with the acquisition of an extraordinary 3.5-metre-long canvas by David Noveliers depicting the procession of giants, which involved huge, clothed wooden figures being paraded through the streets, as well as revellers, musicians and, on the far right of the painting, an enormous black horse draped in cloth.

The Procession of Giants in Brussels on 31 May 1615 (1616; detail), David Noveliers. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven

Doge Marino Faliero Accusing Michele Steno of Insulting the Honor of the Dogaressa (1844), Francesco Hayez

Marino Faliero, also known as Marin Falier, was doge of Venice for only seven months, but in that time he made a significant impression. He launched an abortive coup in 1355 against the city’s aristocracy in an attempt to strengthen his rule, which ended in his capture and beheading – a fate memorialised by Delacroix in a painting of 1826. Lord Byron’s blank verse drama Marino Faliero, Doge of Venice (1821) is about this turn of events, focusing on the (possibly apocryphal) story that Faliero’s coup was conceived as an act of revenge on the aristocrat Michele Steno for casting doubt on the faithfulness of Faliero’s wife, the dogaressa. Now the Yale University Art Gallery has acquired a painting from 1844 by the Italian Romantic painter Francesco Hayez, depicting the moment when Faliero is said to have confronted Steno in the doge’s palace. The work is highly detailed and full of visual drama, from the doge’s seething red eyes to Steno’s bowed head and the expectant faces of the onlookers. Faliero’s arm is outstretched, as if to banish Steno away from the palace; but a closer look reveals that he is in fact pointing to his own throne, on which lines have been scrawled implying that the dogaressa has been unfaithful. The painting was bought from Galerie Canesso and is now on display in Yale’s European galleries.

Doge Marin Faliero Accusing Michele Steno of Insulting the Honour of the Dogaressa (1844), Francesco Hayez. Photo: Yale University Art Gallery

Pallant House Gallery, Chichester

25 works by Julia Margaret Cameron, Paul and John Nash, Eileen Agar and more (acceptance in lieu, donation by Cameron’s great-great-granddaughter)

Anne Hewat, the great-great-granddaughter of the photographer Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–79), built up an impressive collection of British art for her home in Chichester, together with her husband, Angus. The couple were long-standing supporters of Pallant House Gallery in their home town – Angus was a trustee and Anne volunteered there, and they, along with two other donors, donated a plot of land to the museum, allowing it to build a new wing there in 2006. Angus and Anne died in 2014 and 2020 respectively; now Pallant House has announced the acquisition, through the acceptance in lieu scheme, of 25 works of art from the Hewat collection, including photographs taken by Cameron of Alfred, Lord Tennyson and John Herschel, a watercolour by Paul Nash, a linocut by Cyril Power and a colourfully abstracted self-portrait by Eileen Agar. The full set of works is currently on show at Pallant House in the exhibition ‘Julia Margaret Cameron to Eileen Agar: The Hewat Collection’ (until 12 January 2025).

Portrait of young girl with lute guitar (Lady Florence Anson) (1866), Julia Margaret Cameron. Pallant House Gallery, Chichester

Musée du Louvre, Paris

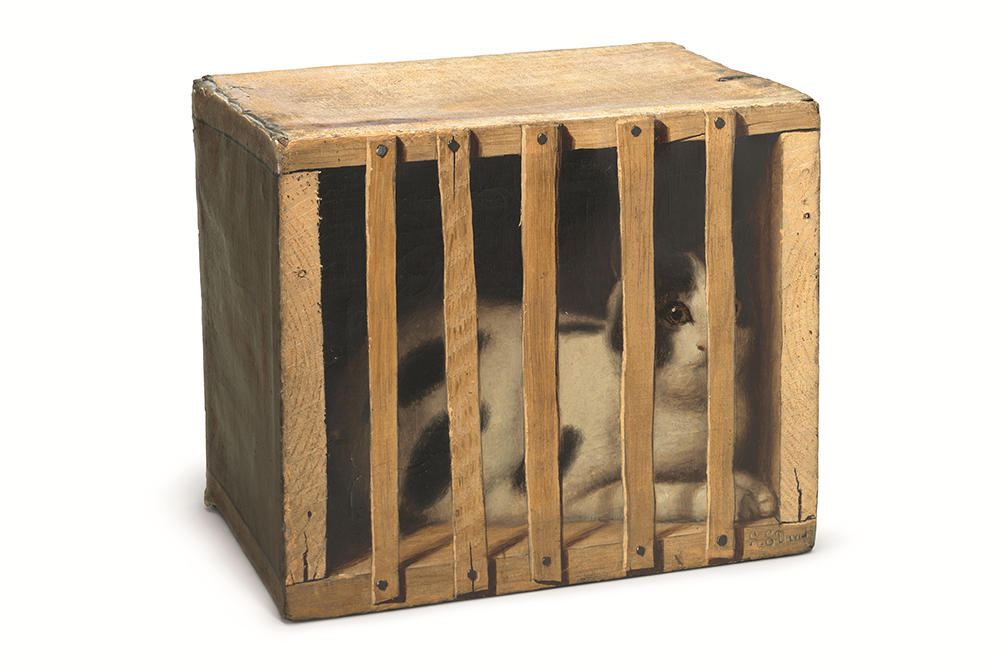

Safe bearing the coat of arms of Louis XIV (1671), Louis Piau

A large chest bearing the coat of arms of Louis XIV, the ‘Sun King’, has been acquired by the Louvre. The king oversaw a blossoming in arts and culture in France, particularly in the decorative arts, his major project being the extensive renovations of and additions to the Palace of Versailles. This chest, made of oak with ornate steel plates and crafted by Louis Piau, the royal locksmith, is one of the few surviving examples of ornate furniture from the early part of Louis XIV’s 72-year reign that can be directly linked to the crown. It joins, among other objects in the Louvre’s collection, the king’s personal jewel casket, decorated with elaborate gold filigree and dating from 1676.

Chest bearing the coat of arms of King Louis XIV, signed and dated by Louis Piau (1671). Photo: © Musée du Louvre, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn/Tony Querrec

[ad_2]

Source link