Category: Photography

Photography Contest Winner Reveals Photo Was AI-Generated, Rejects Prize

[ad_1]

A winner in an international photography competition has renounced his award after revealing that his artwork was generated with the help of artificial intelligence.

German artist Boris Eldagsen said he submitted his image to this year’s Sony World Photography Awards in a bid to test whether such competitions are prepared for the entrance of realistic, AI-generated submissions. His announced win last month in the creative category led him to conclude that they are not.

“AI images and photography should not compete with each other in an award like this. They are different entities. AI is not photography. Therefore I will not accept the award,” he said in a statement last week that was shared on his website.

Eldagsen said he did not initially disclose that his artwork was AI-generated when in December he submitted his piece, titled “Pseudomnesia: The Electrician.” The contest said the submissions could be made using “any device,” he said.

Boris Eldagsen/Sony World Phototgraphy Awards

It was only after his black-and-white image depicting two women was named victor in the creative category that Eldagesn said he revealed to the contest’s organizers that he had received some extra help.

In a message that he said he sent to Creo, which organizes the contest with its World Photography Organisation, he said that he didn’t want any misunderstandings and that after two decades in photography “my artistic focus has shifted more and more to exploring creative possibilities of AI generators.”

In a later follow-up email, he said he wanted to make it clear that his art “was produced as an experiment with AI generators, knowing that there will be [an] outcry amongst the photographers community.”

The contest’s organizers stood by awarding him first place in the creative category, however, stating that it “welcomes various experimental approaches to image making from cyanotypes and rayographs to cutting-edge digital practices.

“As such, following our correspondence with Boris and the warranties he provided, we felt that his entry fulfilled the criteria for this category, and we were supportive of his participation,” Creo’s World Photography Organisation said in a statement shared with HuffPost Tuesday.

Eldagsen was still stripped of the award and any recognition on Creo’s website, however, with the organization reasoning that he rejected the accolade and he admitted to trying to fool the judges.

“Given his actions and subsequent statement noting his deliberate attempts at misleading us, and therefore invalidating the warranties he provided, we no longer feel we are able to engage in a meaningful and constructive dialogue with him,” the organization said.

A new winner will not be named in the creative category, a spokesperson said.

Eldagsen, who did not immediately respond to HuffPost’s requests for comment, said he hopes that his refusal of the award spurs more discussions on AI images in art.

“We, the photo world, need an open discussion,” he said in an online statement. “A discussion about what we want to consider photography and what not. Is the umbrella of photography large enough to invite AI images to enter – or would this be a mistake? With my refusal of the award I hope to speed up this debate.”

This wasn’t the first art contest to be controversially won by AI.

Last year, the Colorado State Fair awarded an AI-generated image a blue ribbon in the fair’s contest for emerging digital artists, sparking some outcry over the award entry’s legitimacy.

The contest’s judges told local news outlet The Pueblo Chieftain that they were unaware that the artwork had been created using AI, but even if they had known, it would have still been awarded first place. A spokesperson for the Colorado Department of Agriculture told the Chieftain that there may be future policy changes.

Creating AI-generated artwork is as simple as entering a series of words into AI art-generating software. One free online program is called Dream. These programs then turn out custom images based on those words.

In Eldagsen’s work, he said his images were “co-produced” using AI image generators. His series of work titled “Pseudomnesia,” which he notes is a Latin term for fake memory, was “imagined by language and re-edited more between 20 to 40 times through AI image generators,” he posted on his website.

[ad_2]

Source link

Art Photo Collector, “How wrong it is for a woman to expect the man to…

[ad_1]

“How wrong it is for a woman to expect the man to build the world she wants, rather than to create it herself.”–Anaïs Nin

Since the beginning of the medium, women have always been a vital part of the development and history of photography. Acknowledging and celebrating their contributions has, regrettably, not been a part of the narrative. Seeking to address this absence, historians/curators Luce Lebart & Marie Robert, along with over 160 female writers have brought us a volume of considerable importance.

Thames & Hudson’s new “A World History of Women Photographers” begins chronologically with Anna Atkins cyanotype experiments in the 1840′s and takes us on a fascinating history to today, expertly demonstrating through time how women photographers have never stopped creating, experimenting and re-interpreting the world. The editors write: “This ‘world tour’ enables us to re-evaluate some women who were celebrated and acknowledged in their own time, to remember others now unjustly forgotten, and to discover others whose work was never exhibited or discussed during their lifetime.”

There are 300 photographers presented in this “manifesto.” Each presents an opportunity for discovery and learning. Many have never been recognized until now. With the publication of A World History of Women Photographers, Lebart & Robert are expanding the history of photography and creating a world we want. –Lane Nevares

[ad_2]

Source link

On “Fleabag”, a Corbyn government and Kenneth Clarke’s tandoori moments

[ad_1]

I FINALLY GOT round to watching a few episodes of “Fleabag” to see what all the fuss is about. A few good scenes, I thought, and a magnificently disgusting character with a beard, but apart from that underwhelming. The breaking of conventions (addressing the camera, graphic sexual references, sleeping with a priest) was tediously conventional; the sentimentality, particularly about a pet hamster, was cloying….“Fleabag” and the “Fleabag”-related hype is nevertheless interesting for sociological reasons: it demonstrates the annexation of yet another area of British life by the self-worshipping upper-middle classes.

Comedy used to be a pretty working-class affair. In the Victorian and Edwardian era the upper-classes (including Edward VII) went to music halls to listen to working-class songs and jokes. Many of the giants of post-war comedy such as Eric Morecambe and Les Dawson (pictured, left) came from the northern working class, their talents honed in working-men’s clubs and local talent contests. The “Carry On” films traded in seaside-postcard smut while taking pot-shots at the pretensions of the British professional classes (“Carry On Doctor” is a masterpiece of doctor-deflation).

“Fleabag” is to comedy what “Coldplay” is to music: a demonstration that yet another working-class redoubt has been thoroughly conquered by the professional classes. Fleabag’s parents live in a giant house with a garden-party sized garden. Her sister is a high-flying executive. Though she’s a bit of a drop-out, she’s a drop-out in the way that only very privileged people can be: she runs a (tediously wacky) café and turns up to work when she wants to. This is as it should be. People should write about what they know and Phoebe Waller-Bridge (pictured, right), the writer of the series, is a descendant of baronets and a product of Saint Augustine Priory, a posh Catholic school. But it is yet another example of British social closure as a tiny elite takes over ever more areas of British life and then congratulates itself on how magnificently rule-breaking they are.

A popular explanation for this great social closure is that the fix-is-in: a tiny clique of hyper-connected metropolitan liberals have seized control of the machinery of cultural production and then throw a few baubles to selected minorities in order to persuade everybody (including themselves) that Britain is still an opportunity society. But I worry that the explanation may be darker: as the working class contracts and loses its cultural self-confidence, so working class institutions such as working men's clubs are dying. The modern equivalents of Les Dawson or the Carry On Team don’t have anywhere to learn their craft while the Phoebe Waller-Bridges of this world drift from independent schools to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art convinced that they’re overturning social conventions and setting the world to rights.

***

PEOPLE ARE finally beginning to take seriously the possibility of a government led by Jeremy Corbyn, the Labour Party leader. Mr Corbyn’s impressive performance in the last general election, in 2017, was largely written off as a protest vote: chunks of Remainer England voted for Mr Corbyn precisely because they thought that he had no hope of actually winning. Now with the Conservative Party determined to destroy itself, and Brexit-related turmoil mounting, people are getting seriously worried.

Businesses are calculating exactly what a far-left government would mean and preparing to act accordingly. Foreign powers are beginning to think seriously about what they would do if Britain were run by a man whose basic foreign policy principle is “whatever America is for I’m against”. The Israelis are terrified about the prospects of a British prime minister who has supported Hamas, a militant Islamist group in Palestine, and indulged anti-Semites in his party’s ranks. I suspect that fear of a Corbyn-led government will soon become a major force in British politics—and not just a vague theoretical fear but a real and vivid fear. People will move. Money will flee. Foreign powers will prepare for the worst.

***

THE BRITISH political system is almost perfectly designed to make a hash of withdrawing from the European Union (EU). The system is an adversarial one: the governing party faces the opposition across a yawning divide and politicians bellow at each other. But leaving the EU demands a series of complicated compromises in the middle. The system is also designed to address a problem and move on to something else: each side states its position, parliament divides, and then you move on. But leaving the EU demands persistence above all: you have to keep worrying away at the same problem for week after week. It’s rather like using a hammer to chop down a tree. This structural problem is only going to get worse when (and if) parliament moves from the withdrawal agreement to the more laborious business of shaping our future trading relationship with the EU.

Kenneth Clarke, who succeeds amazingly well in combining his twin roles as Tory grandee and regular bloke, recently gave a long interview to the Guardian in which he said that he repairs to the Kennington Tandoori every Tuesday evening on his own to enjoy a curry and read a copy of The Economist. A colleague of mine found himself having dinner in that very Tandoori last Tuesday. Sure enough Mr Clarke was sitting there, on his own in a window seat, solidly working his way through his copy of The Economist. When he left his place was taken by Ann Widdecombe, a former colleague of Mr Clarke’s who has just quit the Tories to join Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party. My colleague can’t be completely sure but he doesn’t think Ms Widdecombe was reading The Economist.

Picture credits: REX/Shutterstock/BBC

[ad_2]

Source link

Can AI-generated art be copyrighted? A US judge says not, but it’s just a matter of time | John Naughton

[ad_1]

Evelyn Waugh famously held that taking a keen interest in ecclesiastical matters was often “a prelude to insanity”. Much the same might be said about newspaper columnists taking an interest in intellectual property law. But let us take the risk. After all, you only live once – at least until Elon Musk creates an electronic clone of himself.

On Friday 18 August, a federal judge in the US rejected an attempt to copyright an artwork that had been created by an AI. The work in question is, to the untrained eye at least, no great shakes. It is called “A Recent Entrance into Paradise” and depicts a three-track railway heading into what appears to be a leafy, partly pixellated tunnel and had been “autonomously created” by a computer algorithm called the Creativity Machine.

In 2018, Stephen Thaler, CEO of a neural network firm called Imagination Engines, had listed Creativity Machine as the sole creator of the artwork. The US Register of Copyright denied the application on the grounds that “the nexus between the human mind and creative expression” is a crucial element of protection.

Mr Thaler was not amused and issued a lawsuit contesting the decision, arguing that: AI should be acknowledged “as an author where it otherwise meets authorship criteria”; that ownership of copyright should then be vested in the machine’s owner (ie him); and that the register’s decision should be subjected to judicial review to clarify “whether a work generated solely by a computer falls under the protection of copyright law”.

Which brings us to the district court in Washington DC and Judge Beryl A Howell, who ruled briskly that the register had not erred in denying Thaler’s application for copyright. “United States copyright law,” quoth she, “protects only works of human creation.” She did, however, concede the validity of Thaler’s claim that “copyright law has proven malleable enough to cover works created with or involving technologies developed long after traditional media of writings memorialised on paper” and went on to point out that the most recent version of the US Copyright Act allows copyright on “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed”.

So the law, in all its majesty, is apparently not blind to technological innovation. But, writes Judge Howell, it has always insisted that “human creativity is the sine qua non at the core of copyrightability, even as that human creativity is channeled through new tools or into new media.” Why, had not the supreme court itself ruled that photographs were copyrightable creations of “authors” (AKA photographers)? After all: “A camera may generate only a ‘mechanical reproduction’ of a scene, but does so only after the photographer develops a ‘mental conception’ of the photograph, which is given its final form by that photographer’s decisions.”

Quite so. But when did the supreme court come to this enlightened view? Er, 1884, when the court upheld the power of Congress to extend copyright protection to photography in a case involving a photograph of Oscar Wilde, no less! This is interesting because in 1884 – and indeed until comparatively recently – cameras were essentially dumb, analogue machines. You pointed them at a scene, decided on the required exposure (possibly with the aid of an exposure meter), set the shutter speed and aperture and pressed a button. The image produced by this process was chemically etched on to a glass plate or a strip of celluloid.

And now? Almost all cameras are digital and are in smartphones. You choose what you want to photograph, sure, but everything that happens from then on is done by computation. In many smartphone cameras, the images are “post-processed” by tiny but powerful AIs. (Which is why Apple has a legion of engineers working just on the iPhone camera.) The result is that it’s now rather difficult to take a “bad” photograph – one that that is under- or over-exposed, out of focus or blurred by camera-shake. Accordingly, most of the human “craft” of photography is taken out of your hands. And the creativity involved is boiled down to spotting an opportunity (Cartier-Bresson’s “decisive moment”, perhaps) or a scene, framing it and pressing a button. Everything else is done by AI.

Still, at the moment it meets the “human involvement” criterion of the 1884 judgment and of contemporary copyright legislation. But my hunch is that its days are numbered. Indeed, even Judge Howell seems to agree. “We are approaching new frontiers in copyright,” she writes, “as artists put AI in their toolbox to be used in the generation of new visual and other artistic works. The increased attenuation of human creativity from the actual generation of the final work will prompt challenging questions regarding how much human input is necessary to qualify the user of an AI system as an ‘author’ of a generated work.”

She’s right. And – who knows? – if he lives long enough, Mr Thaler may even get his copyright.

What I’ve been reading

Worldly wisdom

Eleven Theses on Globalisation is the title of a bracing post on his Substack by the economist Branko Milanović.

Well versed

There’s a marvellous essay by the late Seamus Heaney in Salmagundi magazine called Place, Pastness, Poems: A Triptych on the poetic uses of memory.

AI future shock

Read The AI Power Paradox: Can States Learn to Govern AI – Before It’s Too Late?, a sobering essay in Foreign Affairs by Ian Bremmer and Mustafa Suleyman.

[ad_2]

Source link

Portfolio reviews at Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival, Toronto

[ad_1]

© Ian Willms, from the series The Road to Nowhere, 2012-13. Winner of the 2013 Portfolio Reviews Exhibition Award.

Just a heads up to our readers in Canada. On Sunday 4 and Monday 5 May, our Editor in Chief Tim Clark will be participating alongside a whole host of curators and directors, publishers and photo editors who have been brought together for two days during Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival in Toronto, Canada to do reviews for established and emerging artists, with a focus on documentary, photojournalism or photo-based art practices.

This is an important event for artists with projects at advanced stages of development who are seeking opportunities for publishing and exhibiting nationally or internationally- as well as looking for guidance on conceptual approaches or career development advice.

2014 Reviewers include:

Mauro Bedoni Photo Editor, Colors, Milan

Matthew Brower Lecturer in Museum Studies, University of Toronto

Laurence Butet-Roch Photo Editor, Polka, Paris

Johan Hallberg-Campbell International Board of Editors, Photo Raw, Helsinki

Federica Chiocchetti Independent Curator and Founder, Photocaptionist, London

Tim Clark Editor-in-Chief and Director, 1000 Words, London

Stacey McCarroll Cutshaw Editor, Exposure, Los Angeles

James Estrin Senior Staff Photographer, New York Times, New York

Kristen Gresh Assistant Curator of Photographs, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Cheryl Newman Photography Director, The Telegraph Magazine, London

Bonnie Rubenstein Artistic Director, Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival, Toronto

Jonathan Shaughnessy Associate Curator, Contemporary Art, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Stefano Stoll Director, Images Festival, Vevey

Amber Terranova Freelance Senior Photo Editor, The New Yorker, New York

Shelbie Vermette Director of Photography, The Grid, Toronto

Fu Xiaodong Independent Curator, Beijing

Portfolio Reviews Exhibition Award

One artist will be awarded with a solo exhibition presented at the CONTACT Gallery in January 2015. The award includes a $1000 credit at Vistek, and a $2500 credit at Toronto Image Works. Chosen by a jury of international professionals in the field of photography, this award recognises outstanding work presented at the Portfolio Reviews. The programme was created to support and advance the careers of talented emerging photographers.

Related Events

Portfolio Night & Cocktail Reception

Monday 5 May, 7pm

Artists and photographers are given the opportunity to share their work in an open forum with reviewers and invited local professionals.

Stories and Pictures

Tuesday 6 May, 5pm

Join James Estrin from the New York Times and Cheryl Newman from the Telegraph for an evening of lively discussions about identity and documentary today. The evening will also include a Q&A with members of the Boreal Collective moderated by Shelbie Vermette, Director of Photography, The Grid.

Stay for the afterparty with the band Das Piumas.

Presented with the Boreal Collective.

The Review Days take place at The Gladstone Hotel and the cost is $200 for 4 reviews. For those interested in attending, there may still be slots available. Please check with the organisers at Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival here.

[ad_2]

Source link

Jenny Lam Is Making Art For Everyone

[ad_1]

To read about the other Culture Shifters, return to the list here.

When Jenny Lam was 8, she turned down a job offer from Walt Disney Animation Studios.

Her father had mailed sketches of her cartoon cats to three Disney animators, including Eric Goldberg, who drew the Genie in “Aladdin.” Soon after, Lam’s mother received a phone call from Goldberg. He invited Lam and her parents to visit him in Burbank, California.

Lam was on winter vacation, and Goldberg took time out of his break to see her and her family. After flying to the Disney studio, she and Goldberg drew and swapped their cartoon sketches, and he told her she could be a storyboard artist there when she turned 18.

Her response: “But I want to go to college first.”

“That’s how I’ve been through everything, running it on my own and winging it,” she explained over Zoom. “Trial and error. Figuring things out as I go.”

Ever since then, Lam has taken “being fiercely independent” very seriously — and the 35-year-old artist and curator is thriving in the arts, especially photography. This May, during Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, Lam is having a solo art show at the main branch of the Chicago Public Library, featuring 12 photographs she has taken around the city over the past decade with her iPhone 5s. Starting in September, some of her other iPhone 5s photography will be on display in two international exhibitions in South Korea and Italy.

As Lam carves her own path, she is also championing other artists. In her latest online exhibition “Hygge,” which opened in January, she spotlights 30 artists worldwide and showcases their artwork on Artists on the Lam, a blog and platform to support and gather other talented people.

Over the years, Lam has held exhibitions in odd places: the basement of a chapel, a former bank building and a loft above a now-defunct shoe store. She’s also curated many imaginative and rule-breaking shows. In “I Can Do That,” she encourages visitors to touch, replicate or directly change and make marks on the artwork to see if they could improve it.

“When I used to go to some galleries, I felt the cold atmosphere there. But I want to let others know art doesn’t have to be cold,” she said.

Taylor Glascock for HuffPost

Her artistic judgment proved to be correct. Nancy Bechtol, a 73-year-old artist and photojournalist, has been in five Lam-curated shows over the past 13 years, including “I Can Do That.” Lam’s knack for “creating situations and having people collaborate in unique ways” has been “eye-opening” for Bechtol.

“For an artist to let a visitor come in and draw or manipulate your original artwork is quite a leap,” said Bechtol, who was one of the first artists featured on Artists on the Lam. “That’s the Jenny mindset. She thinks in ways that are creatively engaging. She’s embracing people artistically, intellectually, emotionally, in many ways.”

To Lam, art is for everyone — and her online platform helps that to be true.

“People who otherwise wouldn’t have been able to see an exhibition in person at a gallery show — whether its location or now because of the pandemic — can now access it,” she said.

One example is her digital exhibition “Slaysian” — meaning “Celebrating Asian” — which focused on Asian American artists in the Midwest, though she didn’t initially intend to put the gallery online. The in-person group show was originally supposed to open on March 20, 2020, which later became Illinois’ first shelter-in-place day.

“A week before it happened, I was like, ‘We’re gonna postpone it; it’s too dangerous,’” she said. “So, I spent my first week of shelter in place moving the entire show online.”

While the change was unexpected, the result has been exhilarating. “All of a sudden, my gallery became a big thing online where I was getting a lot of press, and many people liked it,” Lam said. “It was a welcome comfort in a frightening time to see people enjoying art.”

She did not “consciously tie” her exhibition with her Asian American identity; she emphasized in the open call for artists that “you don’t have to make art about being Asians.” Yet it was a well-timed defense for her community.

“There was a lot of scapegoating and anti-Asian sentiment. But having all these Asian artists making art and showing our stories provided an antidote to that,” she said. “I didn’t propose that it changed the world or anything, but art can be used for compassion and connection.”

The daughter of Hong Kong immigrants, Lam grew up in Northbrook, a predominantly white suburb in Chicago, where she was often the only Asian in her class.

“For me, it was a point of pride,” she said. “I always felt very proud to be Chinese and to be able to teach people about my culture more.”

Taylor Glascock for HuffPost

Like many Chinese American immigrants, her parents mostly spoke Cantonese to her at home. But they didn’t force her to become a doctor or a lawyer.

“I was fortunate that my parents never pushed me to be anything I didn’t want to be,” she said. “So, I’ve always been an artist from the get-go. I was born an artist.”

Her mom is a retired graphic designer, which, according to Lam, is perhaps the biological origin of her visual talents and gifts. “But it’s funny, because I kind of rejected the graphic design part of art,” she said. “I’m always like, ‘Oh, I can do this on my own. I can teach myself.’”

Even as a baby, she learned English by watching “Sesame Street” and began drawing and scribbling on a piece of computer paper with a pen she grabbed from her mom.

“It’s why to this day, I can’t hold a pencil or a pen the right way. It looks like I’m putting a balled-up fist,” she said.

At age 17, Lam went to Columbia University, instead of an art school, and studied visual arts. “I wanted a general education. As a kid, I was a huge nerd. I just loved learning for the sake of it,” she said. “And also, just in case there was a tiny chance I changed my mind and didn’t want to be an artist anymore. But [that] wouldn’t happen.”

With only 13 students in the program and one art class per semester, Lam likens her studies at Columbia to working in a studio. “We weren’t really taught technique. It would be [more] like concepts. So, it’s good that I was self-taught. I knew how to learn because otherwise, I wouldn’t know what to do,” she said.

Taylor Glascock for HuffPost

In 2005, Lam first heard the word “curator” after joining Postcrypt Art Gallery, the only art-related student club for undergraduates at the time.

Later, as the club president during the last two years of college, she grew to love putting on those “great DIY underground” shows and events.

“It was literally underground because the gallery was in the basement of a chapel, a strange location for an art gallery,” she said. “That’s how I fell in love with curating. So just kind of ‘bouncing,’ making art and curating art for other artists.”

After graduating in 2009 during the recession, Lam returned to Chicago. “I didn’t know what to do. There wasn’t really any opportunity,” she said.

Thankfully, Robin Rios, owner of 4Art Inc. Gallery — where she was an intern one summer during college — invited her to become the head curator. A few months later, in 2010, she curated “Somnambulist,” a dream-related exhibition. The gallery space on the second floor was empty and “raw,” like a “warehouse space,” she said.

This time, Lam’s ability to self-explore came into play as well.

“Later, Robin and I came up with the idea of hanging the artwork from the ceiling beams, which turned out great because it added to the dreamy atmosphere,” she said.

Lam always wants to “pick things up” for herself, she said, so she decided to do something on her own and become an independent curator. That’s how she started Artists on the Lam and curated her first independent show, “Exquisite Corpse,” in June 2011.

“Working for yourself meant making up your own rules,” she explained. “I want to have more flexibility. I want to change things up: both traditional exhibitions and something innovative and interesting.”

During our conversation, Lam kept receiving submissions by email because it was the final day of the open call for “Hygge.”

“It’s just a cozy home show,” she said. “One thing this pandemic has taught us is how to better enjoy the simple pleasure of being in the house with your family, with the people you care about, and appreciating life and art together.”

[ad_2]

Source link

Art Photo Collector, “Reform can only be accomplished when attitudes…

[ad_1]

“Reform can only be accomplished when attitudes change.”–Lillian Wald

Autumn is New York is a delight for many reasons. From the colors to the changing light to the fashion and energy in the art world, the city is alive and flourishing. It is an exciting time to see great work, whether it’s a major museum show, a smaller solo exhibition, auction house preview, or a distinguished art fair.

The Art Dealers Association of America’s (ADAA) The Art Show was founded as a non-profit art fair in 1989 to support the work of the venerable 130 year-old Henry Street Settlement. To date, The Art Show has raised more than $35 million for the organization, demonstrating how art and community can work together for the common good.

This year’s art fair, now in it’s 34th iteration, runs from November 3rd-6th. The show is a must-see and is their largest one yet, with 78 member galleries represented. I am particularly excited to see the work of Harold Mendez and Nyeema Morgan of Chicago’s Patron Gallery. Founded by Julia Fischbach & Emanuel Aguilar, Patron Gallery’s roster of artists is diverse, inclusive and a great insight into what is happening in contemporary art. Along with ADAA’s other prestigious member galleries, many of whom are showing the finest work available today, there is plenty to discover. –Lane Nevares

[ad_2]

Source link

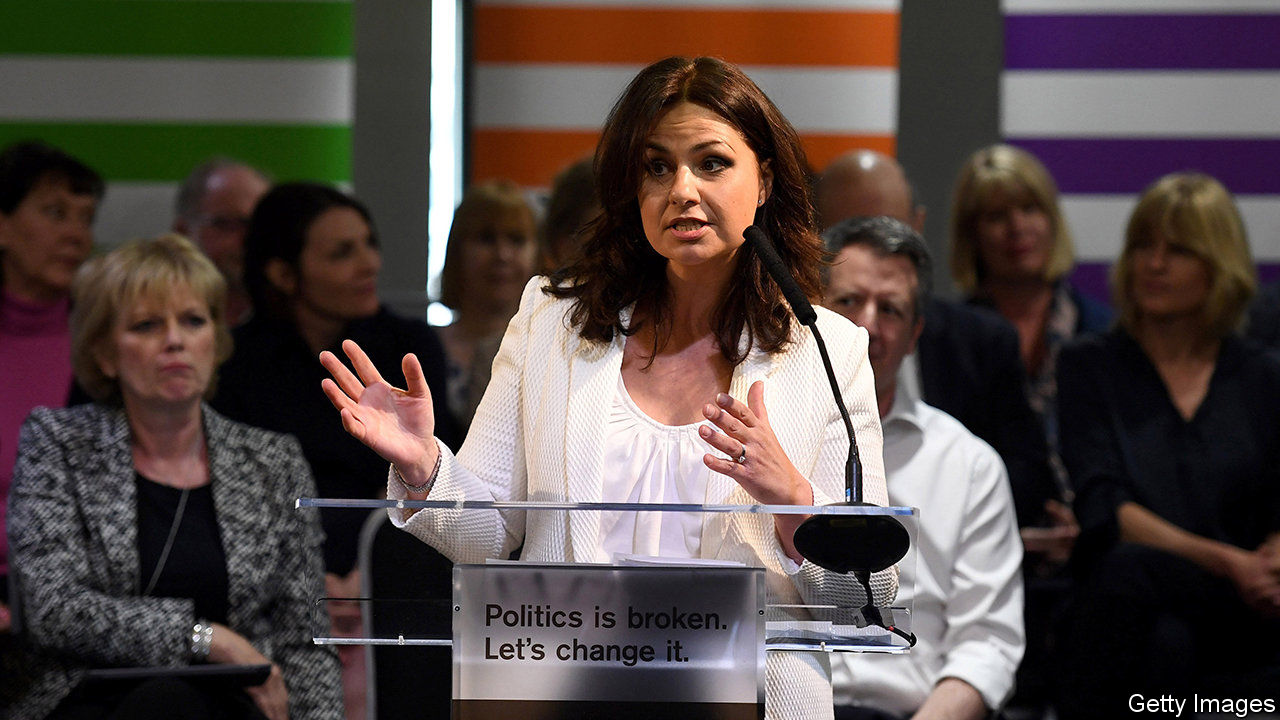

On Change UK’s inadequacies, political agreements and missing Scots

[ad_1]

I WAS much impressed by Heidi Allen’s first speech when she left the Conservative Party to join the Independent Group, now known as the Change UK Party. How could the Conservative high command have ignored such a prodigious talent? But I’m afraid I was very much underwhelmed by her performance at a Beer and Brexit debate on May 14th, organised by King’s College, London. Ms Allen is now the acting leader of Change UK. But even as her job title has grown she seems to have shrunk as a politician. Gently interrogated by Anand Menon, the reigning Brexit guru at King’s, she produced a succession of bland and vague answers that suggested that she’s not capable of either rigorous thought or vigorous organisation.

Ms Allen regurgitated a splattering of good-government platitudes about how Britain needs to be much better at harnessing expertise. Politics should be run more like a business. Parties should take an inventory of the skills and talents of each new intake of MPs. Parliament is run like an old-fashioned gentleman’s club, and so on and so forth. There’s some sense in this—particularly about the skills inventory. But isn’t calling for politics to be run more like a business a bit old hat for a party that presents itself as a change-agent? Donald Trump ran on the promise of using his skills as a businessman to shake up Washington, DC in 2016, and Silvio Berlusconi said the same about Rome in the 1990s. And isn’t the boss of Change UK rather badly placed to call for a more business-like approach to politics? The party has lurched from one disaster to another: failing to establish a brand; faffing about over its name; publicly disagreeing over policies; producing ridiculously slip-shod campaign literature; and, in every way conceivable, allowing itself to be out-performed, out-organised, and out-thought by what is supposed to be the party of out-of-touch bigots, Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party.

Change UK looks as if it will get the Palme d’Or for the most risible projects in recent political history. For a moment it looked as if Tom Watson and the Labour Party’s Social Democratic wing might stage a mass walk-out and join the Tiggers (as Change UK members were known when their nascent party was still the Independent Group). But Mr Watson chose to stay and fight and the Tiggers had to rely on the force of their personalities rather than on numbers. The trouble is that this is far from enough: the founders of the Social Democratic Party back in 1983 were big beasts who were capable of making the weather. Change UK is a collection of small beasts who will probably be swept away by the storm.

***

TO EDINBURGH—that wonderful study in stone as poetry—to debate the future of capitalism with Stewart Wood, a Labour peer, courtesy of Reform Scotland, a think-tank. To be honest we struggled to find big things to disagree about. There is broad agreement across the political spectrum about the toughest problems facing Britain: the over-centralisation of economic and political power in London; the long-tail of low-skilled workers who are trapped in low-paying jobs; the cult of short-termism; financial engineering; the lack of respect for the manufacturing sector. And yet the British political class is instead focusing on policies that are as divisive as possible: on the right, leaving the European Union, and on the left, massive state intervention in the “commanding heights” of the economy such as re-nationalising the utilities and taking 10% of the country’s biggest public companies. While we squabble over what is contentious, we fail to address what we agree about.

***

SCOTLAND AND England are arguably further apart politically than they have been at any time in the history of the Union, and not just because the Scots voted to remain in the EU and the English to leave. The Labour Party once specialised in projecting Scottish politicians to the heights of power in Westminster—Tony Blair, Gordon Brown, John Smith, Ramsay MacDonald, Keir Hardie. The Liberal Party and its various off-shoots had deep roots in Scotland as well as the English provinces (think of Jo Grimond and Charles Kennedy). The aristocratic wing of the Tory Party also boasted deep Scottish connections: Alec Douglas-Home had an estate up there and even David Cameron could boast a Scottish name and Scottish shooting buddies.

British politics is now as English as it has ever been. The only Scotsman in front line politics is Michael Gove, the adopted son of a Scottish fishmonger, and a man capable of reverting from Oxbridge English to Aberdeen Scottish if need be. The people occupying the great offices of state (the prime minister, the chancellor, the foreign secretary) all seem to be in a competition to see who can be the most southern. The Scottish Labour Party has all but died from complacency and mediocrity and the national party has been captured by a clique of London MPs: Jeremy Corbyn and Emily Thornberry both have seats next door to each other in Islington and Diane Abbott and John McDonnell both represent London seats. The Scottish Raj that once ruled over its southern neighbour is scattered to the winds: Gordon Brown and Alistair Darling have returned to Scotland and Tony Blair is in a private jet somewhere in the mid-Atlantic.

Political life in Scotland is dominated by a Scottish National Party (SNP) that has no real relevance down south (though it has 35 MPs, and Ian Blackford, their leader, manfully makes the same speech at Prime Minister’s Questions every week about how Britain is taking Scotland out of the EU against its will). The liveliest issue up north at the moment is the upcoming trial of Alex Salmond on charges including sexual assault and attempted rape. (He says he is innocent of any criminality.) This is dividing the SNP—and Scottish politics in general—between admirers of Nicola Sturgeon, who began her political life as Mr Salmond’s protégé but has since turned against him, and Salmond loyalists who think he is being unjustly accused. The squabble could weaken the SNP’s (increasingly death-like) grip on Scottish politics and prepare the way for significant advances for either the Tories or the Labour Party, with profound implications for the next general election down south.

The other great issue is Ruth Davidson’s re-emergence on the scene after several months on maternity leave. If things had gone well with Brexit, Ms Davidson would be re-appearing just as the Tory Party was putting Brexit behind it and turning to the question of where Britain needs to go now it is leaving the EU (Ms Davidson is a remainer who has reconciled herself to delivering the will of the people). But the Brexit problem is even more fraught today than it was when she went on leave—and the Tory brand is far more toxic. Ms Davidson resisted enormous pressure from within her party to loosen its connection with the Conservative Party south of the border. With Brexit lurching from disaster to disaster and the Tory Party increasingly associated with the likes of Jacob Rees-Mogg, she may rue her decision.

[ad_2]

Source link

Edinburgh art festival 2023 review – from a riveting meditation on borders to magnificent monochromes | Art

[ad_1]

Film scene: a wood-panelled library of some elegance on the Canadian-American border. So precisely on the border, in fact, that a line of black duct tape running across the polished marble floor divides the building between Quebec and Vermont.

It was here, explains our soft-spoken narrator, that three men brought a backpack through the US entrance in 2011, depositing it in a lavatory to be collected by a criminal who then left through the Canadian exit. The bag was full of smuggled guns.

In 45th Parallel, a film by the Turner prize-winning artist Lawrence Abu Hamdan screening at Edinburgh’s Talbot Rice Gallery, the camera now homes in on the narrator, Mahdi Fleifel. A Danish-Palestinian director, Fleifel knows something about borders himself, having been raised in a refugee camp in Lebanon. In the film, he is sitting in the adjoining opera house of the Haskell Free Library. On stage (technically Quebec; the opera house’s seating is in Vermont) is footage of the fatal spot on the Mexican-American border that featured in the notorious supreme court case of Hernández v Mesa.

Jesus Mesa was a US border patrol agent who came across some Mexican children playing on the border one June evening in 2010. He killed unarmed Mexican teenager Sergio Hernández with a single gunshot to the head. All that separated them was 18 metres (60ft) and the invisible border – literally an unmarked line in the sand.

Mexico indicted Mesa for murder, but the US refused to extradite him. The US supreme court voted 5-4 that the American constitution terminates at the border and does not extend – as Mesa’s bullet did –into Mexico. The implications of this verdict (to paraphrase the film’s superb script) are very far-reaching – like the fatal bullet itself.

Drone strikes launched in the US end the lives of Syrian civilians, infants in Afghanistan, a wedding procession in Yemen. Devastating reconnaissance footage is woven into the film’s immensely subtle narrative. Borders prove intangible and absurd, porous in life, and susceptible to the loopholes embodied in the Haskell Library itself, yet also a matter of life and death, according to the law.

Abu Hamdan’s work is always a brilliant fusion of moving image, researched fact and theatrical performance (in this case by the captivating Fleifel). Completed last year, 45th Parallel is his best film yet and not to be missed at this somewhat uneven edition of the annual Edinburgh art festival. All its moral and philosophical dilemmas, its visions, tales and sounds (including an eerie music specially scored for the opera house scenes) are as condensed as a sonnet. The whole vast experience is contained in 15 minutes.

Also at the Talbot Rice Gallery, Irish artist Jesse Jones has turned the next-door gallery, ordinarily full of light, into a pitch-black multimedia installation, The Tower. Out of the darkness looms a sequence of spotlit vignettes: a circular stone portal in the wall, pierced with holes through which you peer into an anchorite’s cell; a girl crouched at the bottom of a towering ladder; a stone statue of a long-haired woman dressed in nothing but animal skins, rising out of a heap of shattered rocks.

On a giant screen, young women sing in ecstatic medieval polyphony. There is a prevailing sense of female community, of the bonds between women, the heights they have to scale, the darkness into which they are pushed, punished, shut away. Bewildering when you first enter, the elements gradually begin to merge into a kind of ancient-modern promenade performance that clearly touches on Hildegard of Bingen and Julian of Norwich. But only the accompanying text, with its references to Ireland’s patriarchal history, and its abortion laws, brings the work into the present or indeed into any kind of meaningful coherence.

More concise, and far less elaborate, is a work by Crystal Bennes in Platform: Early Career Artist award at Trinity Apse, a former gothic kirk off the Royal Mile. Bennes’s subject is the 17th-century economist and politician William Petty and his early version of racial eugenics, a proposal to “improve” Ireland by sending 7,000 English women into forced marriage with Irish men. Their children would all be raised as English Protestants, the girls with a work ethic invoked here in sculptures related to the hard labour of laundry, land and dairy farms. Best of all is a lifesize cameo of the vile Petty, bewigged, impressed into the surface of a basin of what appears to be curdled and solidifying milk.

A few steps further down the steep stone alleys off the Mile is the strangest contrast imaginable, between two well-established artists in prominent public galleries.

Peter Howson has been awarded a three-floor retrospective at the City Art Centre at the age of 65. Nobody even slightly familiar with the strenuous and tormented expressionism of this Ayrshire-raised, Glasgow-trained painter will be surprised to hear that very little has changed down the years. Where Howson once painted the hell of Glasgow life among drunks, vagrants, the poor and unemployed, so he came to record the hell of the Bosnian war with the same brutal machismo, conflating hints of Michelangelo with a raw and sometimes caricatural muscularity.

And so he now paints scenes from the Bible, having a new sense of God’s presence in the world. There are small portrait heads of gnarled saints and apostles and vast martyrdoms and crucifixions. Wall texts declare these works to be “countercultural to the expectations of a 21st-century artist” but they are entirely expected in other ways. Everything, from the delicate to the numinous, compassionate or redemptive, is sacrificed to the force of Howson’s dark brushwork. We are all still in hell.

Directly across the road at the Fruitmarket gallery, Portuguese artist Leonor Antunes has a hanging garden – or perhaps it is more like a sequence of rooms – of knotted and woven works suspended from the ceiling. Each is diaphanous and elegant, crafted in all kinds of materials from silk, twine and hemp to copper wire and pineapple leather. Some feel like screened enclosures, others are more vine-like, reminiscent of bridles or rope ladders.

The works apparently refer to other artists, including Lena Bergner and Trude Guermonprez, Bauhaus designers forced to flee Germany in the 1940s, and Sadie Speight who worked on the Royal Festival Hall. Their names occasionally appear in Antunes’s titles, as if she were talking to them somewhere offstage. And though there is an almost ethereal serenity to this refined and meticulous art, it is also discreet to the point of reticence, if not withdrawal.

The Stills gallery has a magnificent show of monochrome photographs by the veteran Prague-born photographer Markéta Luskačová, focused upon her images of children’s lives. Gawping, gazing, curious, rapt, comforting each other in fights, innocently aping the adults, trying to learn how to be grown up, in hardship or poverty, when still young enough to invent hilarious games involving nothing but their own school jumpers.

At first, it seems they are all from Soviet bloc countries – four to a bed, out on their mother’s back during the potato harvest, watching itinerant jugglers in some far-distant market. But then you notice the familiar stripes of a primary school dress in some English playground in summer and the dreich flat sands of Whitley Bay in Tyne and Wear. The street musician performing with a couple of small puppets, poignant counterparts of the human infants in the buggy beside her, was photographed in London in 1990.

Luskačová’s compositions are as superb as her power of noticing. Girls skip across a playground, linked cardigan to cardigan in a chain of black diamonds. A boy holds his upright dog by the paw, a little friend exactly half his height. A child stands vertical before his grandmother, flat upon the floor, in a configuration like a sign of the cross. It takes a moment before you realise she is dead.

Luskačová wheeled her own small son around the London to which she fled, from communist Prague, in 1975. It is almost as if she takes in the world from his height. A photograph shot in Brick Lane in 1977 shows an encounter between a lion cub and a greyhound, barely restrained on its leash. Behind them stand a pair of small children, equally alive to the staggering moment.

-

The Tower is at the Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh, until 30 September

[ad_2]

Source link

Sean O’Hagan: “If you don’t annoy some people some of the time, you’re not doing your job properly!”

[ad_1]

0

0

1

2015

11488

Michael Hoppen Gallery

95

26

13477

14.0

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-GB

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:"Table Normal";

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:"";

mso-padding-alt:0cm 5.4pt 0cm 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0cm;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:11.0pt;

font-family:"Helvetica Neue";}

Federica Chiocchetti: Could you tell us a little bit about your background prior to your post as photography critic at The Guardian?

Photography was always there in the background as a fascination of mine and several interviews I did for The Observer Review section with the likes of Robert Frank, William Eggleston, Stephen Shore, and Anders Petersen prompted me to start writing about it more. That was about 10 years ago, when there seemed to be an absence of writing on photography in the ‘serious’ papers. It was usually left to the art critic or whoever else was available to review a big exhibition or book. It was not taken seriously as an art form – still isn’t, but to a lesser degree – compared to, say, theatre or film or dance. So, I was very much on a mission to help put that right. It just grew from there and I was offered a regular online forum by The Guardian a few years ago, which became On Photography.

FC: What is your conception of ‘good’ writing on photography? Is there anyone in particular that has inspired you? And what advice would you give to an emerging writer on photography?

SH: Writing that is clear and clear-headed even if it is tackling difficult or elusive or obtuse subject matter. I have a certain responsibility because I work for a newspaper with a huge readership. Many of my readers are regulars but many more may come to a column or a feature out of curiosity and with only a passing interest in the subject. I’d like them to come back. I’m not writing for an art magazine where one can assume that the reader has a certain familiarity with the subject or with the history of conceptualism or whatever. I can’t use dense, theoretical language to deconstruct works by Jeff Wall or Gursky, nor would I want to.

My formative inspirations were non-fiction writers like Joan Didion, in particular her first two collections of essays, The White Album and Slouching Towards Bethlehem. I like Truman Capote’s essays as well, much more than his fiction. And Gay Talese’s classic collection, Frank Sinatra Has A Cold, which has just been published as a Penguin Classics. On the more contemporary front, I’d recommend John Jeremiah Sullivan’s collection, Pulphead: Notes from the Other Side of America, which is a very personal take on music, politics and culture. As far as photography writing goes, it always amazes me how many great photographers are also great writers - Diane Arbus, Robert Adams, Danny Lyon. And Eggleston’s short illuminating afterword from The Democratic Forest still resounds. We ALL need to be more at war with the obvious right now!

FC: How do you discover new talent?

SH: Increasingly, it discovers me. Strange, but true. It’s the power of the internet again. People know where to find you!

I try to stay alert to what people I trust are enthusing about. I read photography mags, blogs, websites – at least the more interesting ones. There is an awful lot of new work out there and I have to be ultra-selective just because of space and the requirements of the job so I see all these other outlets as a kind of filter. And, of course, people send me stuff - books, pdfs, ongoing projects. It’s kind of relentless and so is the demand for an instant response. I worry about that a bit as I tend towards the reflective. I think we should all slow down... and breath. Let things settle. The quick response is journalistic, of course, but it is not necessarily critical. And opinions are not enough. That’s where we live right now, though. I wish there was a slow journalism movement. I really do.

FC: Do you read/appreciate photography theory?

SH: It depends. Good writing is good writing, whatever. But, when I read bad theoretical writing – dense theoretical jargonese – the old punk in me agrees with Nan Goldin, who said recently: “Fucking postmodern and gender theory. I mean, who gives a shit? People made all that crap up to get jobs in universities.” I think it kills the work for people who are not from that academic background. That kind of writing is exclusive by its nature. It often makes things less clear.

That said, I am familiar with theoretical writing. I did an English degree at a time when post-structuralism and semiotics were like time bombs exploding in the academy. I still return to Barthes and Foucault from time to time. I love Barthes when he is at his most personal and Camera Lucida is a very personal meditation on photography and memory and mourning.

I worry about the teaching of photography in colleges and the emphasis on theory. You see degree shows and MA shows where students present half-digested theory and really dull photographs. I think the ascendency of the curator is a cause for concern as well. They sometimes seem more important than the artists, which is something Brian Eno predicted when I saw him gave a lecture at the beginning of the nineties. I like this essay by Paul Graham, which touches on some concerns of mine. I don’t think it helps to exclude people – or images – from the ongoing debate about the meaning of photography. Theory can be a way of entering and decoding a work but, too often, it seems to me like an end in itself. It’s still valid to walk out into the world with a camera and simply take photographs, though there is, of course, nothing simple about doing that well. I often detect a kind of implicit disdain for that approach from curators and academics.

FC: What is the harshest criticism that you received in your career as a photography critic for The Guardian?

SH: Where to begin? You have to become thick-skinned pretty quickly if you venture online. There was a post recently suggesting that a ‘proper’ art critic should have reviewed Lorna Simpson’s show at BALTIC - “she deserves to be reviewed in a context and by a reviewer commensurate with her status!” - which I took personally for about five minutes until I realised the next post had demolished the inherent snobbery of that remark pretty succinctly. I received a fair amount of flak as well as support for my views on The Deutsche Börse Photography Prize a few years ago, when I suggested it was biased towards art photography at the expense of other genres, but that comes with the turf. I guess if you don’t annoy some of the people some of the time, you’re not doing your job properly.

FC: Which British photographers do you feel have been underemphasised by UK photographic institutions?

SH: Oh dear, where to begin? Chris Killip had a major retrospective in Essen, not that long ago, but has not had one here. That is mystifying to me. In fact that whole generation of great British documentarists get short shrift from British institutions. I can only put that down to curatorial bias. If not, what else explains it? I think people in the photography community were relieved when Tony Ray-Jones was finally given a show last year (at Media Space.) Likewise Tom Wood at The Photographers’ Gallery. I know Paul Graham had a big show at The Whitechapel a few years back, but why not at the Tate or the Hayward? It just seems odd at this stage of the game.

FC: What trends do you find interesting at present?

SH: Found photography continues to fascinate people in and out of the photography community – Thomas Sauvin’s Beijing Silvermine project looks like the last word but probably isn’t. I get sent a lot of diaristic work, which is probably the biggest trend. Says a lot about where we live. A lot of it seems solipsistic and has none of the heft of, say, Nan Goldin’s work.

I’ll be glad to see the back of (too) big prints, which everyone seemed to be doing for a moment there, whether the work required it or not. And, please, no more Google Street View projects! I think photographers do tend to get apocalyptic about the post-digital deluge – Instagram etc. – and the sheer numbers can be scary, but most people don’t even see that stuff. For me it’s just another moment in the continuum. I read somewhere that, in the sixties, over half of all households in America had a Polaroid or Instamatic camera, but I don’t think Robert Frank and Garry Winogrand were running around in a panic thinking, “It’s all over for us – everyone’s taking photographs!”

What it does to looking or processing images is another thing, though. We’re all living though a huge social experiment that it is hard to gauge the real meaning of. I’m a bit more concerned with what texting, tweeting and the rest is doing to literacy. Kids’ brains are definitely being rewired. Where will it lead? Who knows?

FC: Do you think that prizes and awards are a good thing?

SH: Yes and no. It’s good to be acknowledged, but there are too many prizes now. And they can tend to be a lottery of sorts. I looked at this year’s Deutsche Börse shortlist and thought, What?! Where’s Viviane Sassen, for example? But, that’s the nature of prizes: it’s four people’s opinions usually – and two of them are curators. I tend to take them with a pinch of salt - unless I’m up for one!

FC: Could you tell us a photobook and an exhibition from the past that blew your mind?

SH: The past is a big country. How about the very recent past? The Robert Adams retrospective at Jeu de Paume in Paris recently was just so impressive - a life in a body of work. I spent ages in there. He’s a living master. At the other extreme, someone who is relatively new. I walked into Tereza Zelenkova’s small show, The Absence of Myth, at Legion TV, a small gallery in Hackney last year and was blown away by the work and the way it was laid out - texts and multiple black and white prints in large frames. She’s a young photographer, but there is something very thoughtful as well as day dreamily melancholic about her approach to the gothic and uncanny. She’s fascinated by Georges Bataille and manages to get something of his aura into the words and pictures. She has her own way of seeing things. That’s what I’ m looking out for.

In terms of historical shows, Eggleston’s Ancient and Modern at The Barbican in 1992 was a game-changer for me. It presented a new way of seeing: the ordinary made luminous, the world as we know it, but slightly skewed.

And photo books...Off the top of my head: Love on the Left Bank by Ed van der Elsken was perhaps the first photobook that made me see the potential of photography to create a staged, semi-fictional, but somehow utterly real, visual narrative. It still amazes me that it was first published in 1957. So far ahead of the game. I also remember coming across Ray’s A Laugh by Richard Billingham in a bookshop in the mid-nineties and being really confused and excited by it. It had a similar impact on me as a great punk or hip-hop record would once have had – that feeling that you were encountering something new and so viscerally powerful that you were not quite sure what to do with it.

I had a similar reaction to Lieko Shiga’s Rasen Kaigan. What’s going on in these pages!? Still not sure, but it’s pretty powerful. And, recently, this photobook arrived though my letterbox and it’s pretty damn exciting, too: Shanxi by Zhang Xaio, published by Little Big Man.

[ad_2]

Source link