TODAY is Brexit day at the Conservative Party conference and Theresa May has opened proceedings with two chunky announcements about Britain’s next steps towards the exit door. First, she intends to include a Great Repeal Act in next year’s Queen’s Speech. This will revoke the 1972 European Communities Act (ECA), the legislation that took Britain into the club and which channels European laws onto British statute books, from the point of Brexit. Second, she will trigger Article 50 (the two-year process by which Britain will negotiate its exit terms) by the end of March 2017. This is earlier than some had expected, as it comes before French and German elections in May and September respectively, and before the next Queen’s Speech. The prime minister is under pressure from die-hard Brexiteers—a gang led by Iain Duncan Smith has just published a package of demands amounting to a recklessly fast and complete break from the European Union—and is offering these two pledges as proof that the wheels of the process are finally starting to turn.

The sequencing of these two milestones is curious and points to a broader truth of the upcoming talks. It would be more natural for Parliament to debate and vote on repealing the ECA before the government invokes Article 50. After all, the latter (moving to leave the EU) is inconsistent with the former (the codification of Britain’s ongoing membership). Moreover, the binary result of the June referendum leaves many important questions unanswered; about the fashion in which the country will leave the club, for example, and the sort of new relationship to which it should aspire. As she begins negotiations next year Mrs May will have no mandate more nuanced than that conferred, informally, by the referendum: take Britain out of the EU. It would make sense for Parliament to deliberate on the next steps before the talks have begun, rather than afterwards, as the prime minister’s proposed timetable implies. After all, Article 50 requires a country leaving the union to issue notification of its intent “in accordance with its constitutional requirements”. Is parliamentary approval not the essence of Britain’s constitutional order?

The point would not be to block Brexit. Though the referendum was not binding, moves by MPs to overrule its result would be a political travesty in the absence of a dramatic shift in public opinion (of which there is no sign, yet). No, the point would be to involve MPs—who, remember, are paid to hold the government to account—in a process that will define not just Britain’s relations with the wider world but the character of its economy and society for the foreseeable future. Different sorts of Brexit lay the foundations for different national futures: open or closed, free-market or protectionist, individualist or paternalist. If MPs have time to chunter about the Great British Bake-Off, a televised baking contest, they have time to weigh in on Brexit. Plenty of authorities agree—last week the constitution committee of the House of Lords ruled that it would be “constitutionally inappropriate” for Article 50 to be triggered without a parliamentary vote. Still, few expect the legal challenges being mounted in support of this argument to succeed.

This is worrying. Repealing the ECA will, for example, give ministers vast discretionary power to amend European laws through statutory instruments. Even if Britain does not initially want to change such laws, many make reference to EU institutions and protocols, so they will need rewriting to make sense; a “Draft Brexit Act” published by Allen & Overy, a law firm, suggests that “deletions, simplifications, shortenings and removal of red-tape” as well as clarification of the “status of guidelines” will all be up for grabs. This will provide plenty of opportunity for ministers to water down or otherwise fiddle with legislation they do not like. Consider the breeziness with which Bernard Jenkin, one of Mr Duncan Smith’s co-authors, insists that how Britain fills the “lacuna in our regulatory landscape…need not be set out in detail” when Parliament overturns the ECA. He even points to the hardly uncontentious field of pharmaceutical regulation as an example. No surprise, then, that lobbyists and lawyers are rubbing their hands at all the business this deluge of barely scrutinised ambiguities will generate.

Moreover, that is just the job of unwinding Britain’s existing relationship with the EU. Simultaneously the country will be negotiating a new settlement, probably including some interim arrangement to kick in after Britain formally leaves the union in early 2019. The possibilities of ongoing membership of the single market, or a free-trade deal and curbs on free movement, will open up myriad questions about the country’s future. And assuming Britain leaves the customs union, it will eventually launch formal trade talks with countries outside the EU.

The sheer quantity of scrutiny will severely test Parliament’s capacity (as well as offering yet more rich pickings for lawyers and lobbyists). That MPs are being marginalised at this crucial early stage is thus a concern: so much of what is to come turns on Mrs May’s initial negotiating strategy. Quizzed on the matter by Andrew Marr on his BBC politics show this morning, she left little room for MPs to hope for a more substantive role as talks advance. Parliament will “have its say” by voting for the Great Repeal Act, she said, and would be informed about non-sensitive details “at various stages” thereafter. She thus echoed David Davis, the Brexit secretary, who last month warned a parliamentary committee that MPs should not expect total transparency.

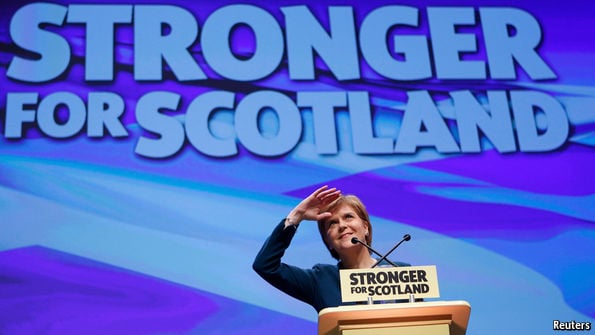

The irony is that Brexit was sold to British voters as a means to take back parliamentary sovereignty from an undemocratic Brussels, but the European Parliament will probably play a more proactive role in the coming negotiations than will Westminster. Though the Council will in practice lead the talks, MEPs have been assured of extensive briefing during the process (Article 218 of the Lisbon Treaty requires that the Parliament be kept “immediately and fully informed at all stages” of an exit negotiation); they have already appointed a point of contact for the talks, Guy Verhofstadt; and most crucially they have a veto on the final deal that will give them huge informal influence over the European institutions’ negotiating posture. Their ability to lobby and shape the process is certainly greater than that of British MPs, whose political freedom of manoeuvre and collective stock of relevant knowledge and experience are both much smaller. The chaotic state of Britain’s opposition Labour Party—which bafflingly opted not to debate Brexit at its conference last week—and the secessionist orientation of its second opposition force, the Scottish National Party, do not help matters.

All of which is not just a shame. It is disturbing. It speaks of a risky centralisation of control over a process whose outcome will shape Britain for generations. Mrs May is essentially competent and cool-headed, more so than any of her three Brexit ministers (Mr Davis plus Liam Fox, the international trade secretary, and Boris Johnson, the foreign secretary). But her time at the Home Office before becoming prime minister also hints at a tendency towards control-freakery and perhaps even a resistance to scrutiny. For her sake and that of Britain, MPs should push back against this. They have probably lost the battle for a vote on triggering Article 50, the ongoing legal challenges notwithstanding. But they should demand proper briefings and opportunities for scrutiny going beyond the pantomime of regular ministerial questions. For example, the new Brexit select committee should enjoy privileged access to sensitive information about the negotiations, just as the Intelligence and Security Committee does about Britain’s spies. Tomorrow, Brexit day over, the Tory conference will turn its attentions to social reform. For Mrs May is determined that her premiership be about more than Brexit. Fair enough. But even the most contentious social reforms come and go, whereas Brexit is permanent and all-encompassing. MPs must ruminate on that distinction and assert themselves accordingly.