Category: Painting

A Contemporary Artist Is Helping Princeton Confront Its Ugly Past

[ad_1]

These days, public sculptures often seem seem intertwined with historical regret. There’s the bronze Robert E. Lee statue in Charlottesville, Virginia; the Roger Taney effigy outside the Maryland State House; the Confederate soldier in front of North Carolina’s Durham County Courthouse. This historical regret has inspired a rush to topple sculptures. But the feelings of remorse and shame have also stirred impassioned debate about the ways in which art ought to reflect America’s complex legacy: Who should embody the values of today? What distinguishes art from political propaganda? And which artists will fill the empty plinths?

Princeton University has one answer to these questions with a new public-art project that confronts the school’s participation in the nation’s early sins. On Monday, the university unveiled Impressions of Liberty, by the African American artist Titus Kaphar. The sculpture is the conceptual core of a campus-wide initiative that begins this fall and aims to reconcile the university’s ties to slavery. The Princeton and Slavery Project’s website has released hundreds of articles and primary documents about slavery and racism at Princeton, which was once jokingly described as the “northernmost outpost of Southern culture.” There is perhaps no better-suited artist than Kaphar to help the school grapple with past inequities and consider the stains of its founders. His art concentrates on the way history is remembered, highlighting the figures and inconveniences, as one 2009 Art in America review described it, who are “habitually … written out of grand historical narratives.”

Princeton is hardly the first college to reckon with the racial injustice that defined its founding, and to seek a kind of rhetorical cleansing. Georgetown, for example, announced last year that it would grant admissions preference to descendants of slaves whose sale it profited from in the early 1800s. Harvard, Brown, Emory, the University of Maryland, and the University of Virginia have also acknowledged their shameful pasts, examining through more traditional academic symposiums how slavery shapes their current environment.

But Princeton’s decision to deploy art is particularly incisive. It captures the extent to which writing the country’s history is as much an emotional process as it is a practical and cerebral one, particularly at a time when issues of historical record are far from settled. This fall, Princeton may begin confronting the wrongs of a relatively small bucolic campus. But the university presents a case study for better understanding the role contemporary art will play in how America confronts its legacy of slavery and discrimination.

Like many American institutions, Princeton shares a raw paradox with its nation: From the start, liberty and oppression were inseparable. Over the last four years, Martha Sandweiss, a Princeton history professor, has mined university and local archives to get a complete picture of the school’s links to slavery. Her research forms the basis of the Slavery Project. On the one hand, according to records, Princeton was a bastion of liberty, educating numerous Revolutionary War leaders and in 1783 hosting the Continental Congress, a pivotal moment in the country’s struggle for freedom and newfound independence. At the same time, Sandweiss found that the institution’s first nine presidents all owned slaves at some point, as did the school’s early trustees. She also discovered that the school enrolled a significant number of anti-abolitionist, Southern students during its early years; an alumni delivered a pro-slavery address at the school’s 1850 commencement ceremony.

“Like many American institutions, Princeton shares a raw paradox with its nation: From the start, liberty and oppression were inseparable.”

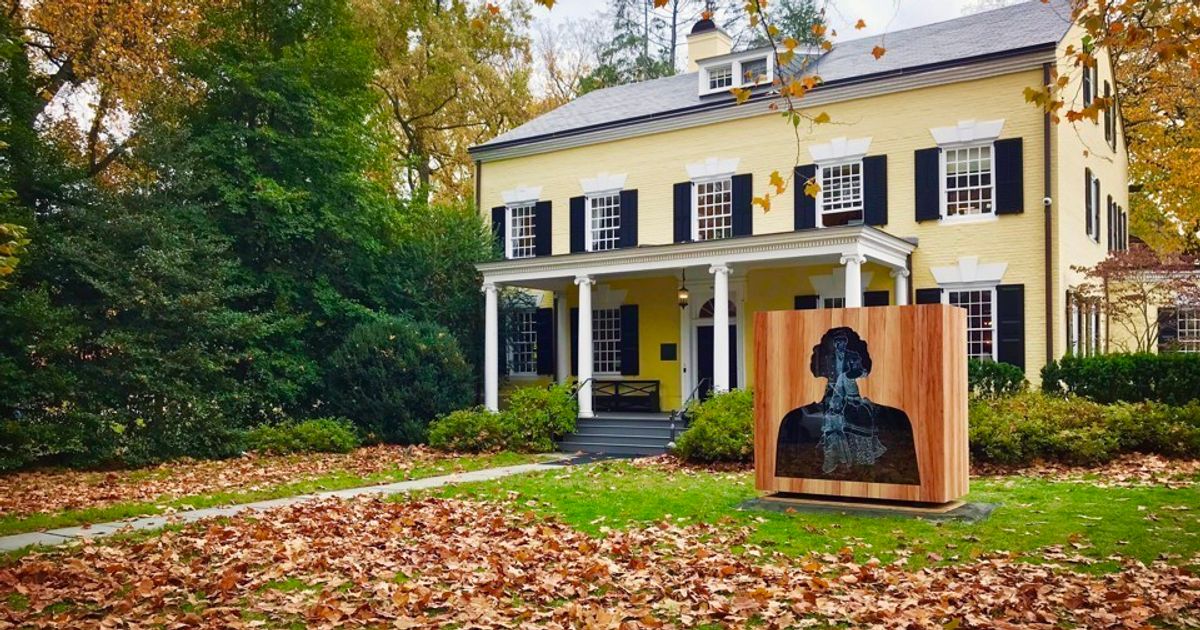

For the next month, Kaphar’s sculpture will occupy the lawn of Maclean House — the former home of university presidents, including Reverend Samuel Finley, who enslaved people there until his 1766 death. “Art is a language,” Kaphar told me during our first interview in his studio. “There is always a narrative coded in painting and sculpture. When you look at something, ask yourself, who is represented and who is invisible?” Impressions of Liberty, he said, is a direct response to the university’s findings that Finley’s slaves were auctioned at Maclean House. His artwork inverts the mythical hero-figure of a founding father — typical of public monuments — and the human beings Finley enslaved on campus. As with much of his art, Kaphar’s goal is to upend Old Master painting techniques to expose how images endure and shape the country’s idea of truths.

RELATED: UVA’s Troubling Past

This summer, I accompanied him on a visit to the Yale University Art Gallery, where we stood before one of his depictions of George Washington (now in Yale’s collection). This three-dimensional painting may be Kaphar’s most aesthetically compelling work yet to challenge ideals in art and U.S. history. Shadows of Libertyemploys a Colonial art tradition — an oil painting of a political leader on his proverbial white horse — but masks Washington with cascading fragments of his slave records and, in a nod to the symbolism associated with African power figures, rusty nails. Kaphar explained how Yale’s classic portraits, by the likes of John Trumbull and Thomas Eakins, inspired his reconsideration as a graduate art student of Washington the patriot and Washington the slave owner. The strips nailed to Washington, according to Pamela Franks, the gallery’s contemporary-art curator, open “new ways of understanding American history” for its museum visitors.

Titus Kaphar’s Shadows of Liberty, 2016, at Yale University Art Gallery (Courtesy of Titus Kaphar and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York)

In a similar vein, the piece Kaphar has sculpted for Princeton features layered photographs, etched in glass, of Finley and black actors dressed in period costumes to represent the slaves the former university president held in his campus residence. Kaphar created a composite bust in negative relief of Finley, coating it with graphite and encasing it in Sycamore wood to echo the campus’s “liberty trees” nearby, which were, according to Princeton legend, planted to commemorate the repeal of the Stamp Act.

“There are no Gods among us. I’m trying to tell the story of America without demonizing or deifying our forefathers,” Kaphar told me over phone in September, weeks after white supremacists converged in Charlottesville, Virginia, to protest the removal of the Robert E. Lee statue. His aim, Kaphar explained, is to create an experience akin to that of a manual-focus camera, that now-anachronistic device in which perspectives slide in and out of view. Kaphar does not want his work “to erase history,” but rather to ask viewers to contend with competing images in the foreground and the background — something the eye and brain struggle to do.

“There’s so much power that happens,” Kaphar said, “when we shift our focus or our gaze — just slightly, momentarily — and confront the unspoken truth.” Asked to describe his reason for back-illuminating Finley’s carved-out bust, he explained, “I’m trying to create a literal space for anyone who passes this sculpture to begin thinking about iconic leaders in history, how glorified images of the past affect the world we live in today.” For generations, slave-owning Christians — including Princeton’s founders — used religious ideas to justify a horrific national practice, he noted; Finley is holding a bible in Impressions of Liberty. But, Kaphar added, “art should never tell anyone what conversation to have. It’s not a didactic sculpture. I want people to sit with the idea that Finley doesn’t represent good or bad.”

The sculpture alone is a bold, exquisite way to visually confront what research has revealed about the school’s roots in slavery. But Princeton University is spreading the mission across various pieces of art through a show this fall entitled “Making History Visible: Of American Myths And National Heroes.” At the exhibit’s entrance, viewers begin with Kaphar’s piece Monumental Inversion: George Washington—a sculpture of the leader astride his horse, made out of wood, blown glass, and steel. The sculpture depicts the former president’s dueling nature: He’s glorified within a great American equestrian monument but he’s also sitting astride a charred cavity, surrounded by glass on the ground. In juxtaposing Kaphar’s artwork and a George Washington plaster bust, “Making History Visible” forces visitors, hopefully, to see and feel the contradiction in colonial leaders who sought freedom from tyranny but did not extend that ideal to slaves. It’s a strong lesson for any college in how a painstakingly curated exhibit can, hopefully, prompt questions about the ways society ought to remember the past, and how those decisions affect the way students understand historic truths today.

Titus Kaphar’s Monumental Inversion: George Washington, 2016, at Princeton University Art Museum (Courtesy of Titus Kaphar and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York)

Art is about the power of symbols, according to James Steward, the museum’s director. “The conversation we are having now about monuments and their visual power are about so many of the same issues in this exhibition,” he said when asked about the country’s removed statues. “Part of our job and what Titus does is to make the past visceral.” Some museum visitors, Steward admits, have had a strong, negative response to Monumental Inversion — which he respects, at least, as an opportunity to open a dialogue.

Like anybody else, students become inured to historical names and concepts taught in the same, conventional classroom ways or frameworks, according to Bradford Vivian, the author of Commonplace Witnessing: Rhetorical Invention, Historical Remembrance, and Public Culture. A professor of communication arts and sciences at Pennsylvania State University, he described why art can provoke, in an individual, forms of reflection, interpretation, and even feeling that she hasn’t before experienced.

Kaphar describes his mission as an attempt to amend history through contemporary art. But not every such effort has succeeded. In 2011, the New York-based artist Fred Wilson met impassioned outcry — from people of all races — for his now-abandoned E Pluribus Unum public-art proposal. Invited by the Central Indiana Community Foundation to create a sculpture for the “Indianapolis Cultural Trail,” Wilson’s design reimagined the only monument in the city’s downtown depicting a black person as a new statue. The design replicated the black man, replacing his manacles with a multicolored flag, and rendering him in an elevated, assertive posture on a plinth of his own; it was to be erected blocks from the original. But local groups didn’t want an artist to critique the city’s visual history with a new sculpture near their old one; a letter published in the Indianapolis Recorder, for example, called for the art to honor one of the city’s prominent black business owners.

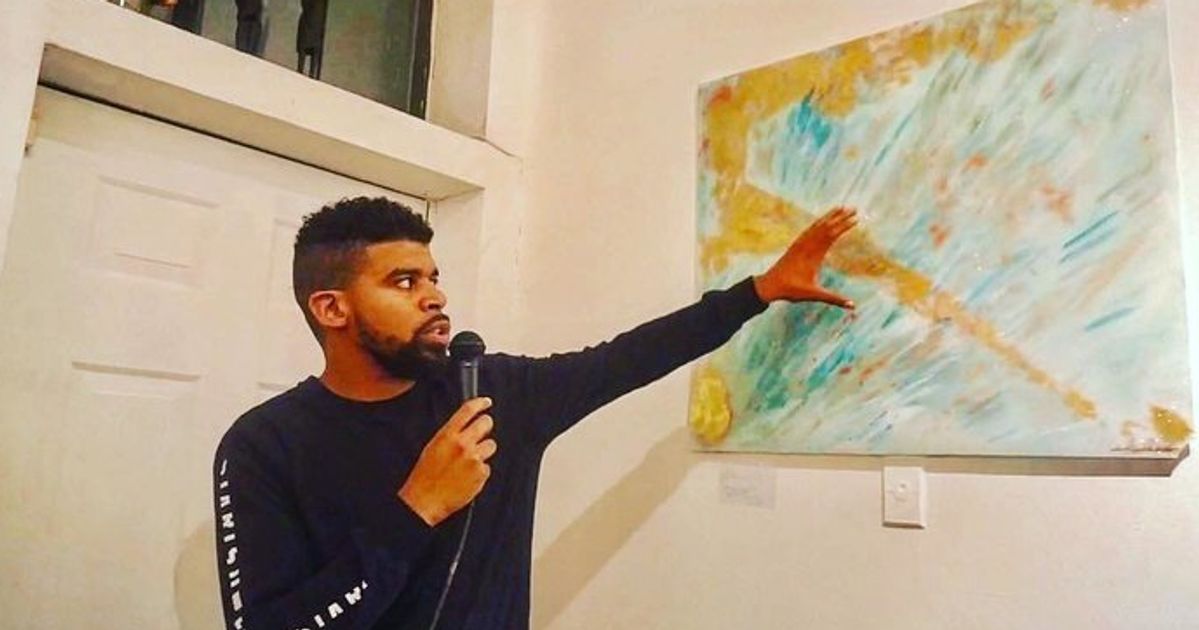

Titus Kaphar stands next to his commission for Princeton University, Impressions of Liberty. (Courtesy of Titus Kaphar and Kaphar Studio)

The University of California, Los Angeles, architecture professor Dell Upton, who wrote the book What Can And Can’t Be Said, has been researching monument building in the contemporary South. He cautions that the impact of Princeton’s art will prove tremendously limited if it can’t show students the vast economic tentacles between past and present. Upton pointed to Hans Haacke’s famous 1971 project, which used photographs and charts to illustrate power structures and financial entanglement in New York real estate as an example of some of the city’s most dubious landlords. Princeton’s racist history enabled it to provide social and political benefits for alumni—an advantage that students will continue to enjoy well into the future.

When Impressions of Liberty is removed from Maclean House in December and enters Princeton’s permanent museum collection, its greatest achievement may lie in the realization that no apology or recompense can ever suffice. But the potential of teaching through art is that there is also a central emotional component, an ingredient that can be missing from more standard ways of learning about one’s predecessors. “Each history deserves disruption,” the Chicago-based artist and founder of the Rebuild Foundation Theaster Gates told me, “but atoning for something is very different from grappling with it.”

Theaster Gates’ In Case of Race Riot II, 2011, at the Brooklyn Museum (Courtesy of Brooklyn Museum)

I asked Gates in October about the extent to which art can reconcile with the past. His 2011 sculpture In Case of Race Riot IIwas recently on view as part of the Brooklyn Museum’s “The Legacy of Lynching”—an attempt to spark “an honest conversation” about racial injustice in America today. In Case of Race Riot II is simplistically haunting art, a wood and metal box housing a coiled fire hose, alluding to the high-pressure water hoses police used on peaceful African American demonstrators in 1963 in Birmingham, Alabama.

“People receive information and empathy in different ways,” he explained. “No civil-rights project can ever fully redeem anything. But when we stumble upon a piece of artwork—in a museum or anywhere else we find it—we might lean in and see better through a visual language. And that language might create a bridge to understanding.”

This story originally appeared on TheAtlantic.com.

More from The Atlantic: A Catfishing With a Happy Ending, Death at a Penn State Fraternity

Support HuffPost

Every Voice Matters

[ad_2]

Source link

Why A $450 Million Painting Attributed To Leonardo Da Vinci Worries Art Historians

[ad_1]

Ahead of Wednesday’s record-breaking auction at Christie’s, during which a painting attributed to Leonardo da Vinci sold for a throat-clenching $450 million, art critic Jerry Saltz voiced some doubts.

Saltz, in an essay for New York magazine, called the portrait of Christ “dead” and “inert,” suggesting that the artwork ― which had been predicted to fetch only $100 million ― is “a sham.” It’s “no Leonardo,” he wrote. Saltz, neither a historian nor an expert in old master work, went on to suggest that Christie’s sale would end poorly. “No museum on Earth can afford an iffy picture like this at these prices.”

And then “Salvator Mundi (Savior of the World)” a 500-year-old portrait of Christ thought to be a copy when it was plucked from an estate sale for a measly $10,000 in 2005, sold for nearly half a billion dollars to an undisclosed private buyer. Suddenly, the controversy surrounding the painting’s authenticity ― its whereabouts over these last few centuries and whether multiple restorations had indelibly altered its surface ― became white noise. Christie’s had managed to rocket past previous auction benchmarks, brokering a historic sum for the seller, Russian billionaire Dmitry E. Rybolovlev’s family trust.

TOLGA AKMEN via Getty Images

Perhaps a museum lacked funds to secure the questionable picture, but a nameless member of the 1 percent surely possessed pockets deep enough.

To most people, $450 million is an unimaginable sum. As Hrag Vartanian at Hyperallergic pointed out, that’s more money than the total estimated cost of the new Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City: $422 million. (It’s also reportedly more money than the Koch brothers are expecting to spend in the 2018 election cycle: $300 million to $400 million.)

“This is a very small step for mankind, but a big step for the art market,” Frank Zöllner, a German art historian and professor at Universität Leipzig, who’s written a book on Leonardo, told HuffPost in a statement over email. “A heavily damaged painting by Leonardo, which was created with the substantial involvement of his workshop after 1507 or even later, achieved a record price, which is significantly higher than the sums that are called for modern masters.”

“Of course, [‘Salvator’] is the symbol of a very unequal, even obscene distribution of wealth in the world,” Zöllner added.

TIMOTHY A. CLARY via Getty Images

Art experts expressed concern with the $450 million price tag, well above the previous record for a painting sold at auction ― $179 million for Picasso’s “Les Femmes d’Alger,” set in 2015.

“I am deeply shocked by” the price, Stephen Campbell, an art history professor at Johns Hopkins University who focuses on Renaissance art, explained. “As a colleague said to me today, the 1 percent — who owns half the planet’s wealth — are looking for the last few places to deposit their wealth. This is a very limited, overvalued sector of the art market. ... The pricing could be controlled in such a way that a public institution could afford it. This is not a celebratory moment.”

Campbell’s unease stems, in part, from the painting’s murky history, a pressure point for a portion of the scholarly community. Campbell saw “Salvator Mundi” in person six years ago. At the time, he was impressed by the lineup of experts willing to vouch for the work, as well as with the scrupulous condition report Christie’s released elucidating the painting’s entire conservation history. The report notes that X-rays and infrared reflectography revealed the signature pentimenti, or visible changes, that helped confirm the painting’s attribution.

“That being said,” Campbell continued, “there is very little Leonardo visible in the painting that was seen yesterday.”

Campbell estimated that only 20 percent of the painting’s surface was rendered in Leonardo’s 16th-century Italian workshop. The rest was carefully reconstructed by conservators, including Dianne Dwyer Modestini. And even that scant 20 percent is in question; there’s a possibility it was executed by Leonardo’s assistants, meticulously trained to mimic his style, and not by the old master himself. The true hand of the artist, Campbell said, is impossible to definitively discern.

“Most post-1500 [Leonardo] paintings are hybrids,” Campbell said. As a result, “when art historians say Leonardo, they’re talking about a category,” he explained. “It’s a ‘Leonardo effect.’”

Campbell is not the only historian with suspicions. Art adviser Todd Levin and Sotheby’s senior international specialist Philip Hook have also expressed measured doubt about the work and its provenance. The painting that once hung in the collection of Charles I of England now appears cracked and worn, overpainted and slightly reimagined. Its whereabouts from 1763 to 1900 are unknown. It resurfaced, only to be sold in 1958 for £45 and disappear once again ― until it popped up in 2005, courtesy of art dealer Alexander Parish. Between 2013 and 2017, the then-consortium-authenticated painting sold once for over $75 million, and again for $127.5 million.

“The attribution of this painting is hotly debated among Leonardo scholars and Renaissance art historians as it always happens with the discovery of new works by a major artist,” Francesca Fiorani, associate dean for the arts and humanities and professor of art history at the University of Virginia, told HuffPost. “Time will tell if the attribution of this panel to Leonardo will stick or whether in a few years the painting will look very different.”

In a statement to HuffPost, a representative for Christie’s cited Luke Syson, curator of Italian paintings before 1500 and head of research at the National Gallery in London; Keith Christiansen, chair of European paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Vincent Delieuvin, curator of 16th century Italian painting at the Musée du Louvre; and Martin Kemp, emeritus professor of the history of art at the University of Oxford, among others, as experts willing to endorse the work as Leonardo. Kemp reiterated his support of the attribution during a phone call with HuffPost on Thursday.

“There were some self-seeking publicity people, journalists, who tried to denigrate the painting, which was so expensive ― that was so valued. But they weren’t serious objections,” Kemp said. As evidence of Leonardo’s handiwork, Kemp homed in on several aspects of the work, including the mysterious orb that appears in Christ’s hand.

“It wasn’t like an ordinary sphere,” Kemp recalled of his time gazing at the painting in person. “It looked like rock crystal. ... It’s not the normal ‘Mundi’ sphere. This is the sphere of the fixed stars, of the cosmos. So Leonardo transmuted it from being a savior of the world to being a savior of the cosmos. That’s the kind of genius he was capable of.”

As for the sum paid to secure the “Salvator,” Kemp agreed it’s “astonishing.” But the painting, which he described as the “spiritual equivalent to ‘Mona Lisa,’” is, he said, “worth what someone’s willing to pay for it.”

“The people who are paying these sums of money undoubtedly would have undertaken due research,” he added. “It is largely a restoration, and it is a damaged picture, but so are a lot of old master works. It’s not the best I’ve ever seen, and it’s not the worst.”

At the end of the day, Campbell concluded that the doubt surrounding the alleged Leonardo doesn’t matter, because, for all practical purposes, the attribution of the artwork was confirmed by the Christie’s sale.

“As a colleague of mine said, ‘Nothing makes a Leonardo more than a hundred- million-dollar price tag,’” Campbell said. “The valuation works in reverse to justify the attribution.” Ultimately, Campbell said that he could accept the painting as a Leonardo, but he could not reconcile with its price. “It’s become a trophy, a market fetish. It’s being taken away from the interest of scholars,” he said.

Lynn Catterson, a part-time lecturer at Columbia University who specializes in the Renaissance, the historical art market and 19th-century Florence, similarly described the painting’s value as “ridiculous and endemic to a planet whose economic disparities are worse than severe. And that is leaving aside issues of authenticity and provenance.”

As Tim Schneider wrote for Artnet News, Christie’s revised fee structure saddles buyers capable of purchasing works over $4 million with a 12.5-percent premium, which ultimately carried the final $400 million bid for “Salvator” to a total payout closer to the half-billion mark. For cultural institutions with limited budgets, the premium allows private buyers to outbid them at auction, leaving cultural touchstones in the hands of the ultra-rich.

This year’s Global Wealth Report, published on Tuesday, confirmed that 1 percent of the world’s population owns half the world’s total household wealth. Just as money has the power to shape democracy, so does it threaten to rewrite art history. If a seismic price tag becomes a more powerful indicator of masterworks than scholarly consensus, provenance and authentication, the sale sets a frightening precedent for, as Saltz put it, #FakeArtNews.

“Most people do not seem to realize that an attribution is an opinion and, as such, legally is not binding,” Maurizio Seracini, an art diagnostician who’s worked extensively with Leonardo’s work, said. “Nevertheless, investors are purchasing art at incredible prices based just on opinions! No wonder why the production of fakes is booming internationally!”

A $450 million valuation is then, by most accounts, unbelievable. However, if any artist could posthumously pull it off, Leonardo might be the most probable candidate.

“On one level, a staggering figure in the art market reminds me of global financial disparity,” Bronwen Wilson, a professor of Renaissance and early modern art at UCLA, said. “But I also find myself ruminating on Dan Brown, video games and lineups to see Leonardo’s works ― for the ‘Mona Lisa,’ ‘The Last Supper,’ and exhibitions ― which is to say that there is also something about Leonardo’s particular purchase on the cultural imagination that plays a role in this instance.”

The cult of Leonardo extends far and wide. He’s become the mythical manifestation of interdisciplinary genius, a superhuman amalgamation of artistic talent, scientific acumen and unbridled curiosity. And there is still another Leonardo work in private hands: “The Madonna of the Yarnwinder.”

As Campbell mentioned, it will be interesting to see what happens if and when this final masterpiece hits the auction block. Perhaps “Madonna” won’t match the hefty price tag of “Salvator,” suggesting soaring auction prices have reached their tipping point. However, if values continue to inflate, the art market’s steel bubble will continue to serve as a glorified piggy bank for the 1 percent.

This post has been updated to clarify the effect of Christie’s buyer’s premium.

Support HuffPost

The Stakes Have Never Been Higher

[ad_2]

Source link

Why A $450 Million Painting Attributed To Leonardo Da Vinci Worries Art Historians

[ad_1]

Ahead of Wednesday’s record-breaking auction at Christie’s, during which a painting attributed to Leonardo da Vinci sold for a throat-clenching $450 million, art critic Jerry Saltz voiced some doubts.

Saltz, in an essay for New York magazine, called the portrait of Christ “dead” and “inert,” suggesting that the artwork ― which had been predicted to fetch only $100 million ― is “a sham.” It’s “no Leonardo,” he wrote. Saltz, neither a historian nor an expert in old master work, went on to suggest that Christie’s sale would end poorly. “No museum on Earth can afford an iffy picture like this at these prices.”

And then “Salvator Mundi (Savior of the World)” a 500-year-old portrait of Christ thought to be a copy when it was plucked from an estate sale for a measly $10,000 in 2005, sold for nearly half a billion dollars to an undisclosed private buyer. Suddenly, the controversy surrounding the painting’s authenticity ― its whereabouts over these last few centuries and whether multiple restorations had indelibly altered its surface ― became white noise. Christie’s had managed to rocket past previous auction benchmarks, brokering a historic sum for the seller, Russian billionaire Dmitry E. Rybolovlev’s family trust.

TOLGA AKMEN via Getty Images

Perhaps a museum lacked funds to secure the questionable picture, but a nameless member of the 1 percent surely possessed pockets deep enough.

To most people, $450 million is an unimaginable sum. As Hrag Vartanian at Hyperallergic pointed out, that’s more money than the total estimated cost of the new Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City: $422 million. (It’s also reportedly more money than the Koch brothers are expecting to spend in the 2018 election cycle: $300 million to $400 million.)

“This is a very small step for mankind, but a big step for the art market,” Frank Zöllner, a German art historian and professor at Universität Leipzig, who’s written a book on Leonardo, told HuffPost in a statement over email. “A heavily damaged painting by Leonardo, which was created with the substantial involvement of his workshop after 1507 or even later, achieved a record price, which is significantly higher than the sums that are called for modern masters.”

“Of course, [‘Salvator’] is the symbol of a very unequal, even obscene distribution of wealth in the world,” Zöllner added.

TIMOTHY A. CLARY via Getty Images

Art experts expressed concern with the $450 million price tag, well above the previous record for a painting sold at auction ― $179 million for Picasso’s “Les Femmes d’Alger,” set in 2015.

“I am deeply shocked by” the price, Stephen Campbell, an art history professor at Johns Hopkins University who focuses on Renaissance art, explained. “As a colleague said to me today, the 1 percent — who owns half the planet’s wealth — are looking for the last few places to deposit their wealth. This is a very limited, overvalued sector of the art market. ... The pricing could be controlled in such a way that a public institution could afford it. This is not a celebratory moment.”

Campbell’s unease stems, in part, from the painting’s murky history, a pressure point for a portion of the scholarly community. Campbell saw “Salvator Mundi” in person six years ago. At the time, he was impressed by the lineup of experts willing to vouch for the work, as well as with the scrupulous condition report Christie’s released elucidating the painting’s entire conservation history. The report notes that X-rays and infrared reflectography revealed the signature pentimenti, or visible changes, that helped confirm the painting’s attribution.

“That being said,” Campbell continued, “there is very little Leonardo visible in the painting that was seen yesterday.”

Campbell estimated that only 20 percent of the painting’s surface was rendered in Leonardo’s 16th-century Italian workshop. The rest was carefully reconstructed by conservators, including Dianne Dwyer Modestini. And even that scant 20 percent is in question; there’s a possibility it was executed by Leonardo’s assistants, meticulously trained to mimic his style, and not by the old master himself. The true hand of the artist, Campbell said, is impossible to definitively discern.

“Most post-1500 [Leonardo] paintings are hybrids,” Campbell said. As a result, “when art historians say Leonardo, they’re talking about a category,” he explained. “It’s a ‘Leonardo effect.’”

Campbell is not the only historian with suspicions. Art adviser Todd Levin and Sotheby’s senior international specialist Philip Hook have also expressed measured doubt about the work and its provenance. The painting that once hung in the collection of Charles I of England now appears cracked and worn, overpainted and slightly reimagined. Its whereabouts from 1763 to 1900 are unknown. It resurfaced, only to be sold in 1958 for £45 and disappear once again ― until it popped up in 2005, courtesy of art dealer Alexander Parish. Between 2013 and 2017, the then-consortium-authenticated painting sold once for over $75 million, and again for $127.5 million.

“The attribution of this painting is hotly debated among Leonardo scholars and Renaissance art historians as it always happens with the discovery of new works by a major artist,” Francesca Fiorani, associate dean for the arts and humanities and professor of art history at the University of Virginia, told HuffPost. “Time will tell if the attribution of this panel to Leonardo will stick or whether in a few years the painting will look very different.”

In a statement to HuffPost, a representative for Christie’s cited Luke Syson, curator of Italian paintings before 1500 and head of research at the National Gallery in London; Keith Christiansen, chair of European paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Vincent Delieuvin, curator of 16th century Italian painting at the Musée du Louvre; and Martin Kemp, emeritus professor of the history of art at the University of Oxford, among others, as experts willing to endorse the work as Leonardo. Kemp reiterated his support of the attribution during a phone call with HuffPost on Thursday.

“There were some self-seeking publicity people, journalists, who tried to denigrate the painting, which was so expensive ― that was so valued. But they weren’t serious objections,” Kemp said. As evidence of Leonardo’s handiwork, Kemp homed in on several aspects of the work, including the mysterious orb that appears in Christ’s hand.

“It wasn’t like an ordinary sphere,” Kemp recalled of his time gazing at the painting in person. “It looked like rock crystal. ... It’s not the normal ‘Mundi’ sphere. This is the sphere of the fixed stars, of the cosmos. So Leonardo transmuted it from being a savior of the world to being a savior of the cosmos. That’s the kind of genius he was capable of.”

As for the sum paid to secure the “Salvator,” Kemp agreed it’s “astonishing.” But the painting, which he described as the “spiritual equivalent to ‘Mona Lisa,’” is, he said, “worth what someone’s willing to pay for it.”

“The people who are paying these sums of money undoubtedly would have undertaken due research,” he added. “It is largely a restoration, and it is a damaged picture, but so are a lot of old master works. It’s not the best I’ve ever seen, and it’s not the worst.”

At the end of the day, Campbell concluded that the doubt surrounding the alleged Leonardo doesn’t matter, because, for all practical purposes, the attribution of the artwork was confirmed by the Christie’s sale.

“As a colleague of mine said, ‘Nothing makes a Leonardo more than a hundred- million-dollar price tag,’” Campbell said. “The valuation works in reverse to justify the attribution.” Ultimately, Campbell said that he could accept the painting as a Leonardo, but he could not reconcile with its price. “It’s become a trophy, a market fetish. It’s being taken away from the interest of scholars,” he said.

Lynn Catterson, a part-time lecturer at Columbia University who specializes in the Renaissance, the historical art market and 19th-century Florence, similarly described the painting’s value as “ridiculous and endemic to a planet whose economic disparities are worse than severe. And that is leaving aside issues of authenticity and provenance.”

As Tim Schneider wrote for Artnet News, Christie’s revised fee structure saddles buyers capable of purchasing works over $4 million with a 12.5-percent premium, which ultimately carried the final $400 million bid for “Salvator” to a total payout closer to the half-billion mark. For cultural institutions with limited budgets, the premium allows private buyers to outbid them at auction, leaving cultural touchstones in the hands of the ultra-rich.

This year’s Global Wealth Report, published on Tuesday, confirmed that 1 percent of the world’s population owns half the world’s total household wealth. Just as money has the power to shape democracy, so does it threaten to rewrite art history. If a seismic price tag becomes a more powerful indicator of masterworks than scholarly consensus, provenance and authentication, the sale sets a frightening precedent for, as Saltz put it, #FakeArtNews.

“Most people do not seem to realize that an attribution is an opinion and, as such, legally is not binding,” Maurizio Seracini, an art diagnostician who’s worked extensively with Leonardo’s work, said. “Nevertheless, investors are purchasing art at incredible prices based just on opinions! No wonder why the production of fakes is booming internationally!”

A $450 million valuation is then, by most accounts, unbelievable. However, if any artist could posthumously pull it off, Leonardo might be the most probable candidate.

“On one level, a staggering figure in the art market reminds me of global financial disparity,” Bronwen Wilson, a professor of Renaissance and early modern art at UCLA, said. “But I also find myself ruminating on Dan Brown, video games and lineups to see Leonardo’s works ― for the ‘Mona Lisa,’ ‘The Last Supper,’ and exhibitions ― which is to say that there is also something about Leonardo’s particular purchase on the cultural imagination that plays a role in this instance.”

The cult of Leonardo extends far and wide. He’s become the mythical manifestation of interdisciplinary genius, a superhuman amalgamation of artistic talent, scientific acumen and unbridled curiosity. And there is still another Leonardo work in private hands: “The Madonna of the Yarnwinder.”

As Campbell mentioned, it will be interesting to see what happens if and when this final masterpiece hits the auction block. Perhaps “Madonna” won’t match the hefty price tag of “Salvator,” suggesting soaring auction prices have reached their tipping point. However, if values continue to inflate, the art market’s steel bubble will continue to serve as a glorified piggy bank for the 1 percent.

This post has been updated to clarify the effect of Christie’s buyer’s premium.

Support HuffPost

The Stakes Have Never Been Higher

[ad_2]

Source link

Lizzie

[ad_1]

[ad_2]

Source link

A Painting Today: “Milkin’ It”

[ad_1]

8 x 12"

oil on panel

sold

The next time you're lucky enough to stand in front of an original painting by Johannes Vermeer, imagine yourself, in 1657 in the Netherlands. You're standing behind the artist as he's painting in his studio on the top floor of a nice townhouse and the only lighting is the blue daylight coming through a window and the candles lighting his palette and canvas. Their maid, an older, sturdier woman poses beside the window, seemingly unaware of the viewer, pouring milk in a ceramic bowl with stale bread used as props on the table. Nothing fancy. Just a domestic woman doing her everyday chores.

The Milkmaid is one of Vermeer's most-famous paintings - one of a few that survived a fire. And lucky for us. Vermeer appreciated light like no other artist of his time. The woman against the white wall, the glimmer of white on the stream of milk being poured, the left side of her face and clothing lit as the rest recedes into shadows. And his details. Right down to the nails in the wall and seeds on the loaf of bread. Just wow.

The Milkmaid has traveled all over the globe and is currently back home at the Rijkmuseum in Amsterdam. Thanks go to Cindy Pronk, a photographer who lives in Holland and offered her original photo for a painting reference during this time when traveling and museum visits have been put on hold. I really appreciate the generosity of others.

[ad_2]

Source link

Missy

[ad_1]

[ad_2]

Source link