Irving Berlin was a Jewish immigrant who loved America. As his 1938 song “God Bless America” suggests, he believed deeply in the nation’s potential for goodness, unity and global leadership.

In 1940, he wrote another quintessential American song, “White Christmas,” which the popular entertainer Bing Crosby eventually made famous.

But this was a profoundly sad time for humanity. World War II – what would become the deadliest war in human history – had begun in Europe and Asia, just as Americans were starting to pick up the pieces from the Great Depression.

Today, it can seem like humanity is at another tipping point: political polarization, war in the Middle East and Europe, a global climate crisis. Yet like other historians, I’ve long thought that the study of the past can help point the way forward.

“White Christmas” has resonated for more than 80 years, and I think the reasons why are worth understanding.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GJ36gbGlm8Y[/embed]

Yearning for unity

Christmas in America had always reflected a mix of influences, from ancient Roman celebrations of the winter solstice to the Norse festival known as Yule.

Catholics in Europe had celebrated Christmas with public merriment since the Middle Ages, but Protestants often denounced the holiday as a vestige of paganism. These religious tensions spilled over to the American colonies and persisted after the Revolutionary War, when slavery divided the nation even further.

After the Civil War, many Americans pined for national traditions that could unify the country. Protestant opposition to Christmas celebrations had relaxed, so Congress finally declared Christmas a federal holiday in 1870. Millions of Americans soon adopted the German tradition of decorating trees. They also exchanged presents, sent cards and shared stories of Santa Claus, a figure whose image the cartoonist Thomas Nast perfected in the late 19th century.

The Christmases that Berlin and Crosby “used to know” were those of the 1910s and 1920s, when the season expanded to include the nation’s first public Christmas tree lighting ceremony and the appearance of Santa Claus at the end of Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade.

Despite these evolving secular influences, Christmas music and entertainment continued to emphasize Christianity. Churchgoers and carolers often sang “Silent Night” and “Joy to the World.”

‘The best song anybody ever wrote’

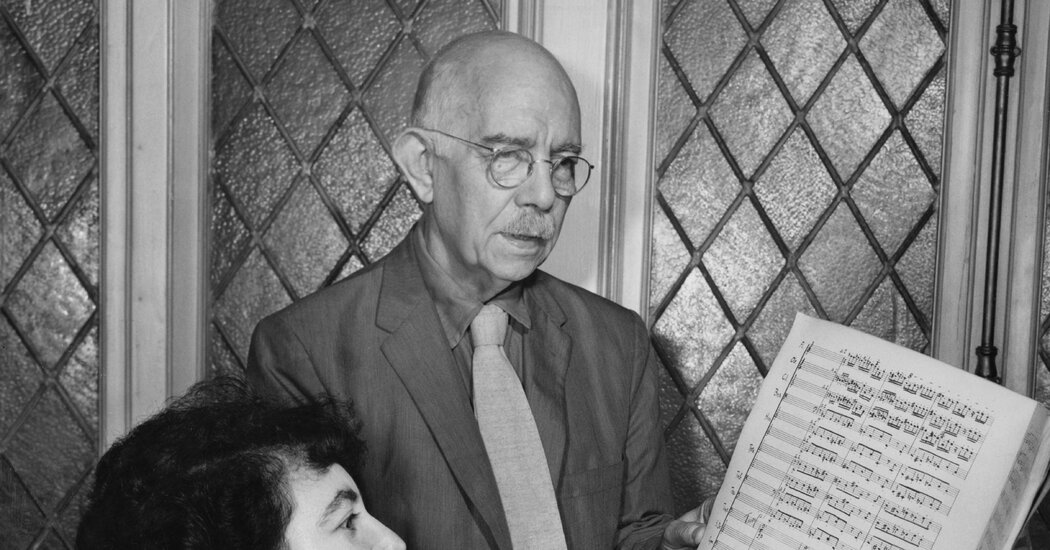

Berlin’s inspiration for the song came in 1937, when he spent Christmas in Beverly Hills. He was near the film studios where he worked but far from his wife, Ellin – a devout Catholic – and the New York City home in Manhattan where they had always celebrated the holiday with their three daughters.

Being apart from Ellin that Christmas was particularly difficult: Their infant son had died on Dec. 26, 1928. Irving knew his wife would have to make the annual visit to their son’s grave by herself.

By 1940, Berlin had come up with his lyrics. In his Manhattan office, he sat at his piano and asked his arranger to take down the notes.

“Not only is it the best song I ever wrote,” he promised, “it’s the best song anybody ever wrote.”

Berlin had connected his lonesome Christmas to the broader turmoil of the time, including the outbreak of World War II and fraught debates about America’s role in the world.

This new song reflected his response: a dream of better times and places. It evoked a small town of yesteryear in which horse-drawn sleighs crossed freshly fallen snow. It also imagined a future in which dark days would be “merry and bright” once again.

This was a new kind of Christmas carol. It did not mention the birth of Jesus, angels or wise men – and it was a song that all Americans, including Jewish immigrants, could embrace.

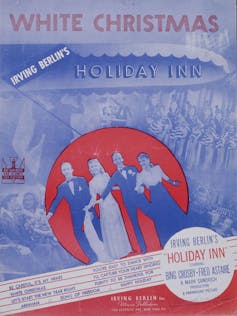

Berlin soon took “White Christmas” back to Hollywood. He wanted it to appear in his newest musical, one that would tell the story of a retired singer whose hotel offered rooms and entertainment, but only on American holidays. He titled the film “Holiday Inn” and pitched it to Paramount Pictures, with Crosby as the lead.

Fighting for ‘the right to dream’

Raised in Spokane, Washington, Crosby had launched his music career in the 1920s. A weekly radio show and a contract with Paramount led to stardom during the 1930s.

With his slim build and protruding ears, Crosby did not look the part of a leading man. But his easygoing demeanor and mellow voice made him immensely popular.

“Holiday Inn” premiered in August 1942. Reviewers barely mentioned the song, but ordinary Americans couldn’t get enough of it. By December it was on every radio, in every jukebox and, as the Christian Science Monitor newspaper noted, in nearly “every home and heart” in the country.

The key reason was the nation’s entry into World War II.

“White Christmas” was not overtly patriotic, but it made Americans think about why they fought, sacrificed and endured separation from their loved ones. As an editorial in the Buffalo Courier-Express concluded, the song “provided a forcible reminder that we are fighting for the right to dream and for memories to dream about.”

This made it a song all Americans could embrace, including those not always treated like Americans.

GraphicaArtis/Getty Images

Affirming faith in humanity

Berlin and Crosby didn’t set out to change how Americans celebrate Christmas. But that’s what they ended up doing.

Their song’s universal appeal and phenomenal success launched a new era of holiday entertainment – traditions that helped Americanize the Christmas season.

Like “White Christmas,” popular songs such as “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” (1943) tapped into a longing for being with friends and family. “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” (1949) and other new songs celebrated snow, sleigh rides and Santa Claus, not the birth of Jesus.

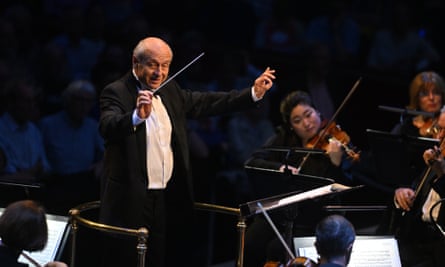

Robert R. McElroy/Getty Images

“White Christmas” had already sold 5 million copies by 1947 when Crosby recorded “Merry Christmas,” the first Christmas album ever produced. On the album, “White Christmas” appeared alongside holiday classics such as “Jingle Bells” and “Santa Claus Is Coming to Town.”

Hollywood followed suit. In the popular 1946 film “It’s a Wonderful Life,” for example, bonds of family and friendship proved their value just in time for Christmas.

Faith was affirmed, but it was a faith in humanity.

Over the coming decades, Christmas entertainment continued to reach new audiences.

The upbeat songs of Phil Spector’s 1963 album “A Christmas Gift for You,” for example, appealed to baby boomers. Producers also catered to younger audiences with television specials such as “A Charlie Brown Christmas” and “How the Grinch Stole Christmas.”

Hollywood then rediscovered Christmas during the 1980s, largely because of “A Christmas Story,” a film that didn’t exactly view Christmas through rose-colored glasses. While satirizing the chaos and angst of the holiday season, the film nonetheless embraced Christmas, warts and all. A steady stream of Christmas films followed – “Scrooged,” “Home Alone,” “Elf” – where themes of nostalgia, family and togetherness were ever-present.

Since the 1940s, the Christmas season has become even more inclusive. A 2013 Pew Research survey found that 81% of non-Christians in the U.S. celebrate Christmas. Yes, the holiday has also become more commercial. But that, too, has made it all the more American.

Amid these changes, Irving Berlin’s song has been a holiday mainstay, reminding listeners of what makes them not just American, but human: the importance of home, a longing for togetherness and a shared hope for a better future.