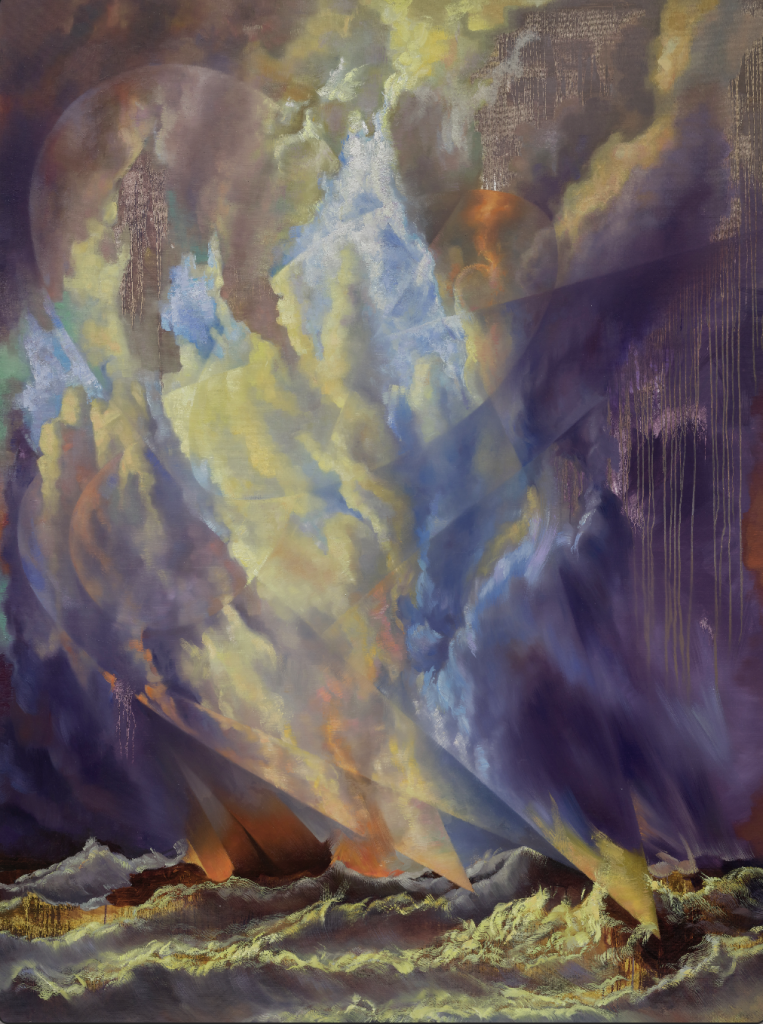

Artist Maria Kreyn dwells in the eye of the storm. For the past year, she’s spent her days painting monumental seascapes in her Williamsburg, Brooklyn, studio. The subject matter is an unlikely choice for a contemporary artist, but Kreyn’s aqueous scenes are mesmerizing.

“This series of work is new for me. I’ve been developing the works over the last couple of years somewhat in secret,” said Kreyn during a visit to her studio. Crashing waves, prismatic skies, and crepuscular rays of light all build into visual crescendos, creating scenes reminiscent of the works of the great Romantic painters J.M.W. Turner and Caspar David Friedrich.

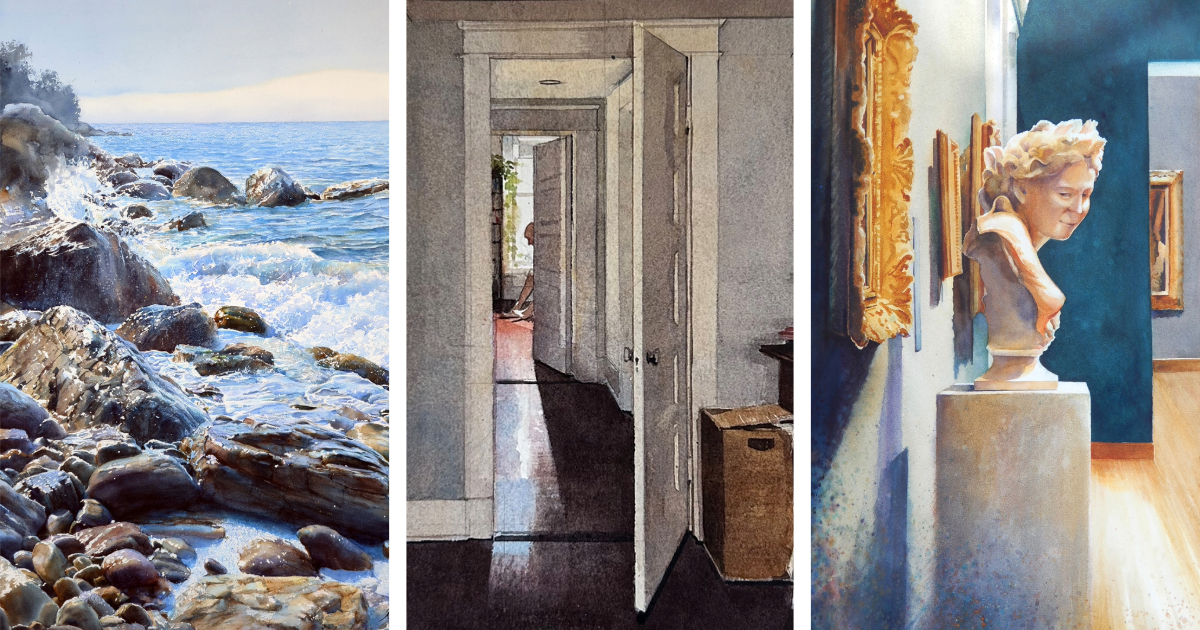

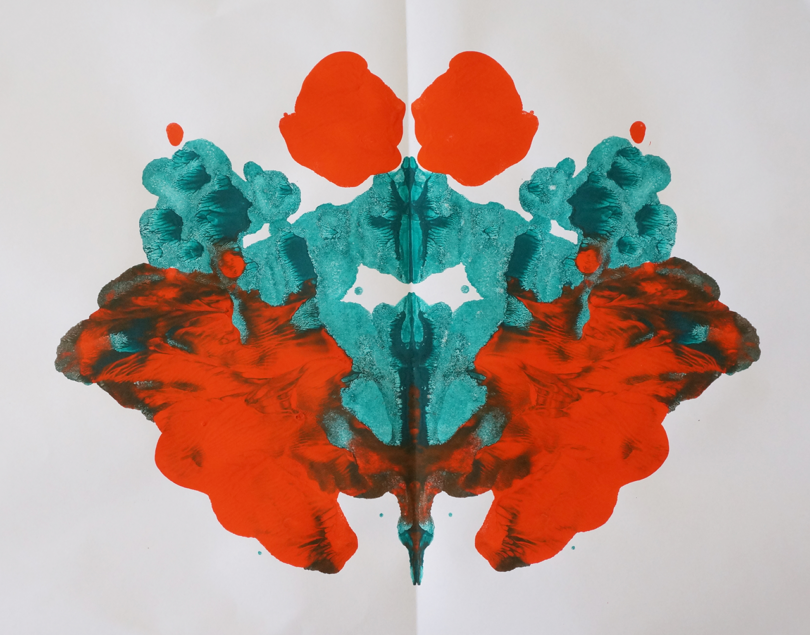

Installation view “Maria Kreyn: Chronos” at St George’s Anglican Church in Venice, 2024.

But these swirling tempests are also unequivocally contemporary. Geometric, almost spiritualist forms, refract throughout the compositions, as if, for a moment, the divine order of the universe were revealed.

Right now, 10 of these paintings are on view in “Chronos” at an exhibition at the St. George’s Anglican Church in Venice, coinciding with the 60th Venice Biennale (through June 22). The exhibition is organized by the Ministry of Nomads Art Foundation led by dealer Maria Vega, with whom Kreyn has previously collaborated. It’s a lush show and follows up to two solo exhibitions last fall— “Untune a String” at the Hole in New York in the fall of last year, her first showing with the gallery, as well as “Lensing a Storm” with the Ministry of Nomads in London.

Kreyn made these works with Venice in mind. “Maria Vega asked me ‘What’s your next dream?’ And I looked at her honestly and said ‘Venice.’ I love the interface of the city with the water and the dialogue with the weather, the climate, and the way the world is changing. There’s no other place like it,” she said.

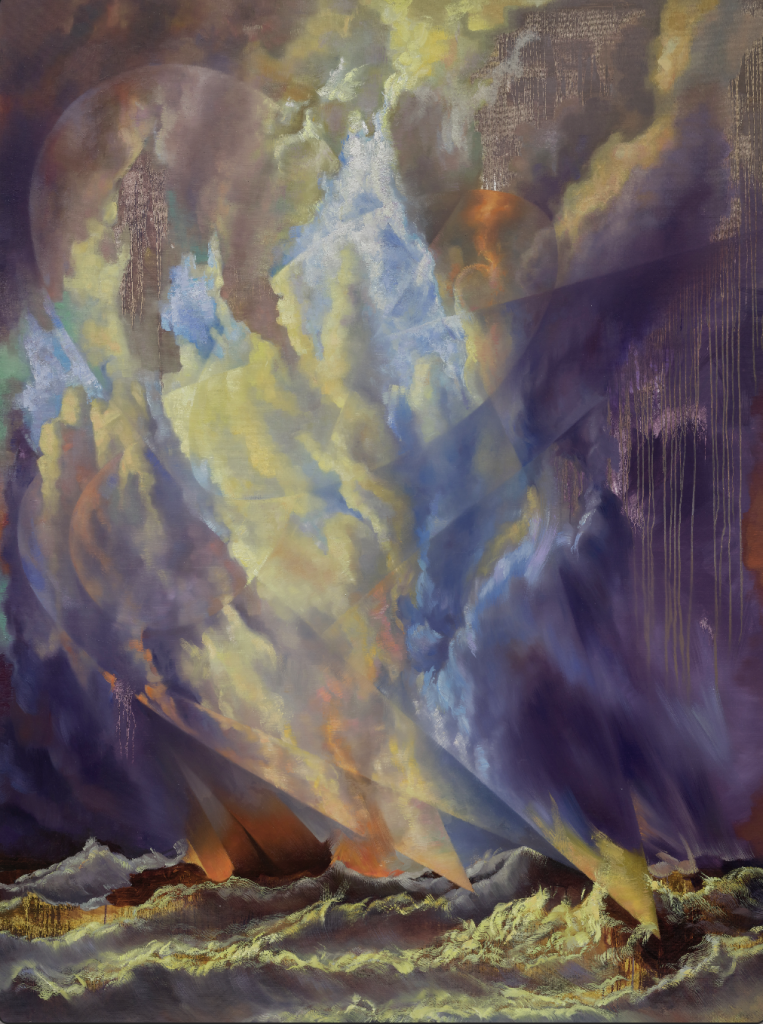

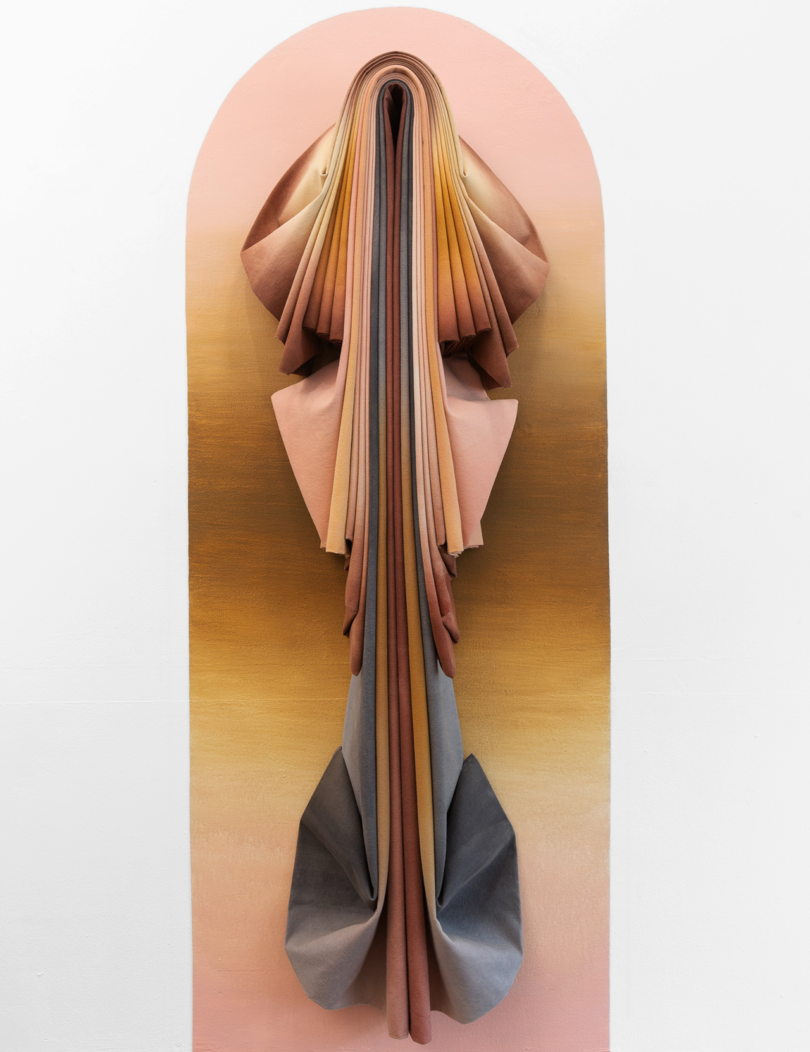

Maria Kreyn, Folding Time I (2024). Courtesy of the artist.

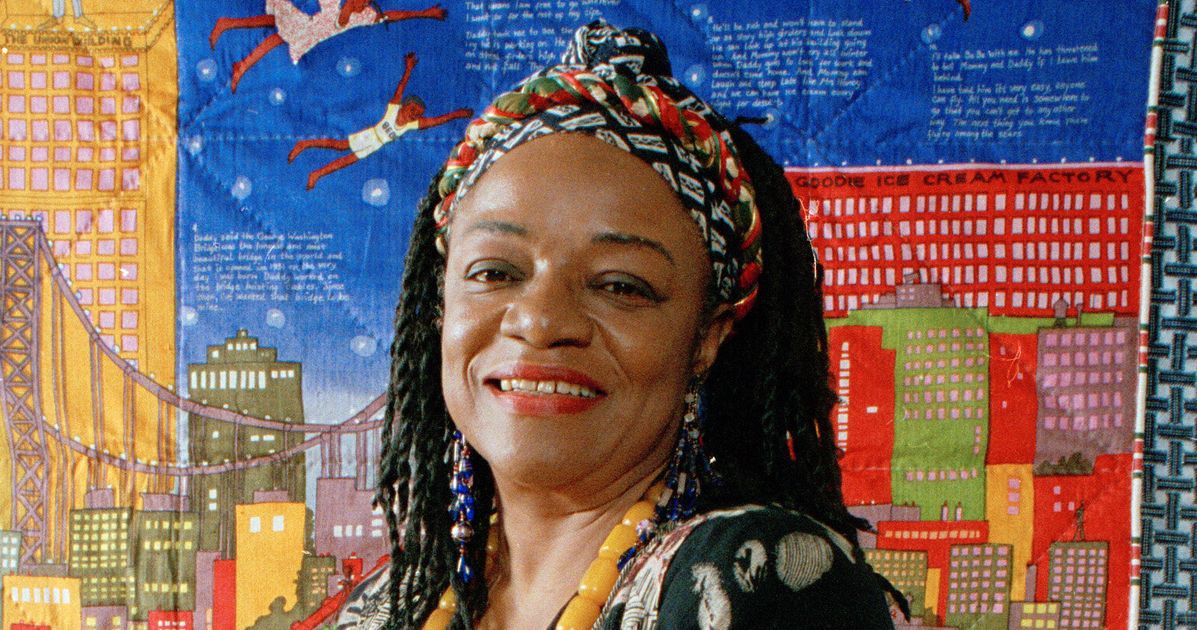

“Chronos” is a significant moment for the New York painter, whose career has followed an unorthodox and highly personal path. Born in Russia in 1987, Kreyn came to the U.S. with her parents and sister as a child. A bit of a polymath, Kreyn studied mathematics and philosophy at the University of Chicago, and ultimately taught herself to paint, learning from studying the works of artists like El Greco and Diego Velazquez. Throughout her twenties, Kreyn, slowly but surely, began building her painting career through word-of-mouth commissions, outside of the gallery model.

“I spent 10 years painting the figure in a way that may have appeared more academic than it was. The underpinnings of the work may seem classical because I’ve been looking at Old Master paintings since I was a child. I became obsessed with figuring out how to create deep atmospheric space,” she explained.

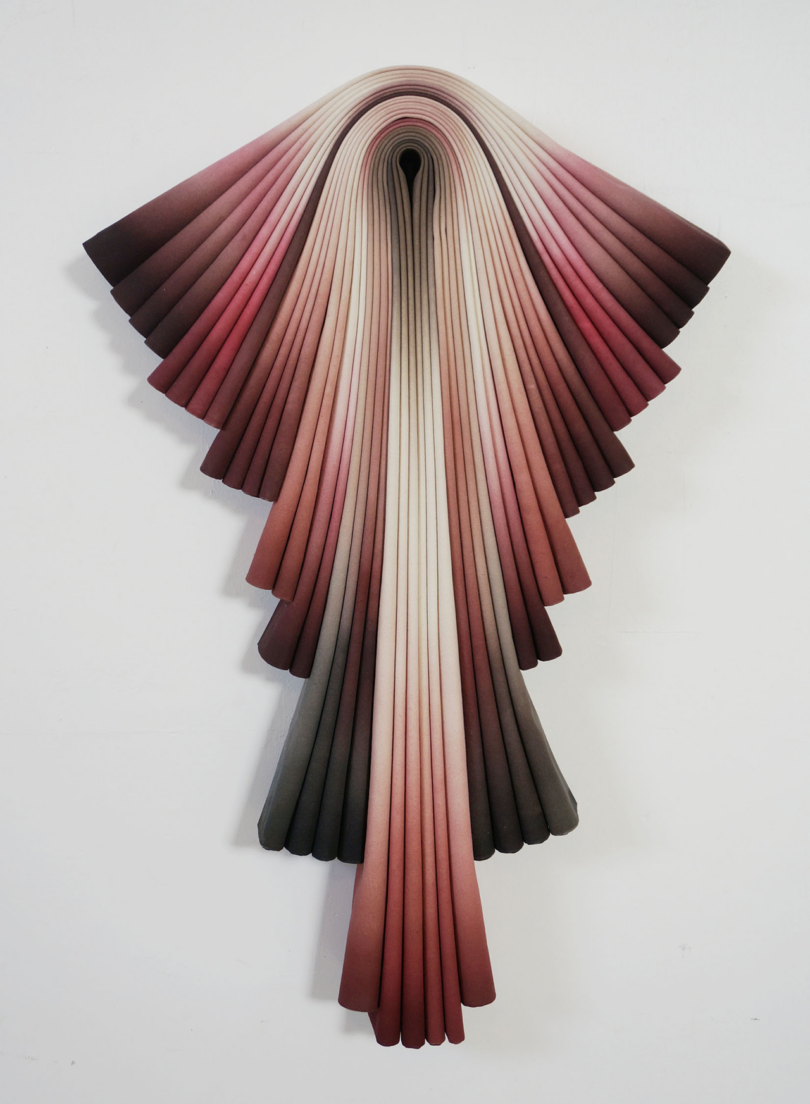

Maria Kreyn, Past is Prologue (2024). Courtesy of the artist.

Kreyn has often skirted the institutional art world, rarely showing with galleries. Instead, she has found opportunity and inspiration at unlikely intersections. This series of storms emerged after the artist was commissioned by none other than Andrew Lloyd Webber to complete an eight-painting series based on William Shakespeare’s works, called the Shakespeare Cycle.

“The painting for ‘The Tempest’ was the last and became the most abstract. With my figurative work, I’d been trying to touch the complexity of emotion and human experience and the range of light and darkness,” she explained, “After making this work I thought: what happens if I just zoom out from the figure to the point where you don’t even see the figure? Where maybe a human presence is implied, but I can play around with paint in a way that opens up a new realm of freedom stylistically.”

Kreyn’s Shakespeare Cycle works are now on permanent display in the lobby of London’s historic Theater Royal Drury Lane. These paintings also appeared in The Crown. That’s not the first television cameo, either; a painting of Kreyn’s also drives the plot of Shonda Rhimes’ ABC television show The Catch.

All to say, her paintings have thrived in third spaces and St. George’s Anglican church is no exception. The austere space of the church adds new resonances to these at-once ominous and ethereal paintings.

“These are meant to be emotional landscapes that are complex, ambiguous, and open-ended,” Kreyn explained. “These storms are like the gaze of a portrait, a vortex, and portal into something that feels eternal, and almost like an icon, without it being religious at all.”

Here, Kreyn’s color palette leans towards the Mannerist, with acidic, impossible hues that hint at global pollution. For example, in the painting, Folding Time I tones of reddish browns and purple blues can be read either as the uncanny hues of a dystopian future or the antiqued effects of age on color. The spaces of creation and destruction merge. In this way, the exhibition, and the church, become a place of reverence for the sublime power of the seas and skies while acknowledging the anxiety of our precarious ecological moment.

For the artist, those moments of connection are the ultimate reward for exhibiting. She’s still not so sure her works belong in traditional galleries, however.

“A lot of things have taught me that paintings aren’t exclusively for galleries,” she said, “Paintings are for human beings. I mean that in the deepest possible way.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.