Famed Sculptor Richard Serra, Known As The 'Poet Of Iron,' Dies At 85

[ad_1]

Considered one of his generation's most preeminent sculptors, Serra was known for turning walls of rusting steel into large-scale pieces of art.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

Considered one of his generation's most preeminent sculptors, Serra was known for turning walls of rusting steel into large-scale pieces of art.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

ALGIERS, Algeria (AP) — Officials in Algeria are chiding television stations over the content choices they’ve made since the start of Ramadan last week, injecting religion into broader discussions about how the country regulates content and advertising in media.

Their criticisms come amid broader struggles facing journalists and broadcasters, where television stations and newspapers have historically relied heavily on advertising from the government and large state-aligned enterprises in the oil-rich nation.

After meeting with station directors on Sunday, Algerian Communications Minister Mohamed Lagab accused networks of not respecting ethical and professional lines, calling their programmatic choices “out of keeping with the social traditions of our society and especially the sacredness of the month of Ramadan.”

Lagab, a former journalism school professor, preemptively rebuffed accusations of censorship, arguing that his ministry’s push didn’t run counter to Algeria’s constitutional press freedom guarantees.

“Television stations have the right to criticize, but not by attacking our society’s moral values,” he said.

Though he did not explicitly name any specific stations or programs, Lagab cited soap operas as a particular concern. His ministry last week summoned a director for the country’s largest private station, Echourouk, over a soap opera called “El Barani” that showed characters consuming alcohol and snorting cocaine — depictions that sparked rebuke from viewers concerned they were incompatible with Ramadan.

Lagab also criticized stations for dedicating excessive airtime to advertising, so much so that it rivaled the run time of certain shows. “If we put advertising (and programs) side by side, we would conclude they last longer than the soap operas broadcast,” Lagab said.

His remarks followed statements from Algeria’s Authority of Audiovisual Regulations, which polices television and radio stations. Throughout March, it has called on national television stations to rein in advertising and respect families and viewers during Ramadan, a holy month observed throughout the Muslim-majority country and broader region.

Lagab’s two-pronged attack — against stations’ content and advertising — is the latest challenge facing Algerian television stations, which are preparing for deepened financial strain as the government prepares new regulations on advertising in media. In anticipation of a new law, stations, especially private ones, have ramped up advertising to an unprecedented extent, hoping to rake in profits before the government sets new limits.

The advertising blitz has been particularly pronounced since Ramadan began last week. As demand increases for food and other consumer products used throughout the holy month, stations have found no shortage of advertisers.

Even if stations don’t change course after meeting with Lagab, experts say the government’s criticisms are unlikely to escalate into punishments like sanctions or fines.

“Most of these channels are politically aligned with the government and zealously support it,” said Kamal Ibri, a journalist whose news website closed for lack of advertising revenue.

Algeria’s largest television stations are a mixture of publicly and privately owned. Networks including the private Echourouk, private El Bilad and the state-owned ENTV broadcast news and other programming, including soap operas. In prior years, viewers have grown accustomed to special Ramadan-specific programs during that period.

Though some private channels have begun platforming opposition parties recently, few broadcast pointed criticisms of the government. Those that do have in recent years been penalized.

Journalist Ihsane El Kadi ‘s media company, which oversaw web television and radio programming was shuttered and had its equipment confiscated. He was sentenced to prison for “threatening state security” in April 2023.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

For weeks now, the world has been awash in conspiracy theories spurred by weird artifacts in a photographic image of the missing Princess of Wales that she eventually admitted had been edited. Some of them got pretty crazy, ranging from a cover-up of Kate’s alleged death, to a theory that the Royal Family were reptilian aliens. But none was as bizarre as the idea that in 2024 anyone might believe that a digital image is evidence of anything.

Not only are digital images infinitely malleable, but the tools to manipulate them are as common as dirt. For anyone paying attention, this has been clear for decades. The issue was definitively laid out almost 40 years ago, in a piece cowritten by Kevin Kelly, a founding WIRED editor; Stewart Brand; and Jay Kinney in the July 1985 edition of The Whole Earth Review, a publication run out of Brand’s organization in Sausalito, California. Kelly had gotten the idea for the story a year or so earlier when he came across an internal newsletter for publisher Time Life, where his father worked. It described a million-dollar machine called Scitex, which created high-resolution digital images from photographic film, which could then be altered using a computer. High-end magazines were among the first customers: Kelly learned that National Geographic had used the tool to literally move one of the Pyramids of Giza so it could fit into a cover shot. “I thought, ‘Man, this is gonna change everything,’” says Kelly.

The article was titled “Digital Retouching: The End of Photography as Evidence of Anything.” It opened with an imaginary courtroom scene where a lawyer argued that compromising photos should be excluded from a case, saying that due to its unreliability, "photography has no place in this or any other courtroom. For that matter, neither does film, videotape, or audiotape.”

Did the article draw wide attention to the fact that photography might be stripped of its role as documentary proof, or the prospect of an era where no one can tell what’s real or fake? “No!” says Kelly. No one noticed. Even Kelly thought it would be many years before the tools to convincingly alter photos would become routinely available. Three years later, two brothers from Michigan invented what would become Photoshop, released as an Adobe product in 1990. The application put digital photo manipulation on desktop PCs, cutting the cost dramatically. By then even The New York Times was reporting on “the ethical issues involved in altering photographs and other materials using digital editing.”

Adobe, in the eye of this storm for decades, has given a lot of thought to those issues. Ely Greenfield, CTO of Adobe’s digital media business, rightfully points out that long before Photoshop, film photographers and cinematographers used tricks to alter their images. But even though digital tools make the practice cheap and commonplace, Greenfield says, “treating photos and videos as documentary sources of truth is still a valuable thing. What is the purpose of an image? Is it there to look pretty? Is it there to tell a story? We all like looking at pretty images. But we think there's still value in the storytelling.”

To ascertain whether photographic storytelling is accurate or faked, Adobe and others have devised a tool set that strives for a degree of verifiability. Metadata in the Middleton photo, for instance, helped people ascertain that its anomalies were the result of a Photoshop edit, which the Princess owned up to. A consortium of over 2,500 creators, technologists, and publishers called the Content Authenticity Initiative, started by Adobe in 2019, is working to devise tools and standards so people can verify whether an image, video, or recording has been altered. It’s based on combining metadata with exotic watermarking and cryptographic techniques. Greenfield concedes, though, that those protections can be circumvented. “We have technologies that can detect edited photos or AI-generated photos, but it’s still a losing battle,” he says. “As long as there is a motivated enough actor who's determined to overcome those technologies, they will.”

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

Ariana Grande holds the No. 1 spot on Billboard’s album chart this week with “Eternal Sunshine,” beating out new releases by Kacey Musgraves and Justin Timberlake.

“Eternal Sunshine,” Grande’s first new studio album in almost four years, stays at the top for a second time with the equivalent of just over 100,000 sales in the United States, including 115 million streams and 13,000 copies sold as a complete package, according to the tracking service Luminate.

Grande’s total was down 56 percent from its opening week, giving it enough — by a thin margin — to succeed over Musgraves’s “Deeper Well,” which started with the equivalent of 97,000. “Deeper Well,” Musgraves’s second LP since winning album of the year at the Grammys in 2019 with “Golden Hour,” starts at No. 2 with 38 million streams and 66,000 copies sold. Those sales included 37,000 copies of the album’s nine vinyl editions — among them a picture disc showing cardinals in a tree and another featuring “scented sleeves.”

“Everything I Thought It Was,” Timberlake’s first new album since “Man of the Woods” six years ago, opens in fourth place with the equivalent of 67,000 sales. It is Timberlake’s first solo studio album not to make it to No. 1 since “Justified,” which went to second place in 2002.

Also this week, Morgan Wallen’s “One Thing at a Time” is No. 3 and Noah Kahan’s “Stick Season” is No. 5.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

I want to talk for a moment about categories. You have occupied many — butch, queer, woman, nonbinary — yet you’ve also said you’re suspicious of them.

At the time that I wrote “Gender Trouble,” I called for a world in which we might think about genders being proliferated beyond the usual binary of man and woman. What would that look like? What would it be? So when people started talking about being “nonbinary,” I thought, well, I am that. I was trying to occupy that space of being between existing categories.

Do you still believe that gender is “performance?”

After “Gender Trouble” was published, there were some from the trans community who had problems with it. And I saw that my approach, what came to be called a “queer approach”— which was somewhat ironic toward categories — for some people, that’s not OK. They need their categories, they need them to be right, and for them gender is not constructed or performed.

Not everybody wants mobility. And I think I’ve taken that into account now.

But at the same time, for me, performativity is enacting who we are, both our social formation and what we’ve done with that social formation. I mean, my gestures: I didn’t make them up out of thin air — there’s a history of Jewish people who do this. I am inside of something, socially, culturally constructed. At the same time, I find my own way in it. And it’s always been my contention that we’re both formed and we form ourselves, and that’s a living paradox.

How do you define gender today?

Oh, goodness. I have, I suppose, revised my theory of gender — but that’s not the point of this book. I do make the point that “gender identity” is not all of what we mean by gender: It’s one thing that belongs to a cluster of things. Gender is also a framework — a very important framework — in law, in politics, for thinking about how inequality gets instituted in the world.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

The Liste Art Fair in Basel, Switzerland, has announced the participating galleries for the 2024 edition. Running concurrently with Art Basel and in the Messe Basel, where Art Basel also takes place, this year’s fair will feature 91 galleries from 35 countries.

Among the exhibitors are 22 first-time participants including Tokyo’s Yutaka Kikutake, the Los Angeles–based gallery murmurs, Silke Lindner from New York, and Rele, which has locations in Lagos, London, and Los Angeles.

The 2024 edition will also feature 65 solo and 16 group presentations, five joint booths, for a total of more than 100 contemporary artists represented with an overarching theme of “the complex relationship between humans and the environment,” according to a release.

This year, the Friends of Liste group has given financial help to 12 galleries including Bombon from Barcelona, Spain; Crisis from Peru; and the South Korean gallery Cylinder.

Liste Art Fair Basel will take place June 10–16 at Messe Basel’s Hall 1.1. The fair’s digital format, Liste Showtime Online, will open on June 5 for previews and to the public from June 10–23. Their second digital format, Liste Expedition Online, is already accessible.

The full exhibitor list follows below. (Galleries marked with * indicate first-time exhibitors.)

| Exhibitor | Location(s) |

| a. Squire* | London |

| Addis Fine Art | Addis Ababa/London |

| Afriart | Kampala |

| Bel Ami | Los Angeles |

| Blue Velvet | Zurich |

| Bombon | Barcelona |

| Brunette Coleman* | London |

| Callirrhoë* | Athens |

| Capsule | Shanghai |

| Chris Sharp* | Los Angeles |

| Ciaccia Levi | Paris/Milan |

| Cibrián* | San Sebastian |

| CLC Gallery Venture | Beijing |

| Clima | Milan |

| Coulisse* | Stockholm |

| Crisis | Lima |

| Cylinder* | Seoul |

| Damien & The Love Guru | Brussels/Zurich |

| diez | Amsterdam |

| Drei | Cologne |

| Edouard Montassut | Paris |

| eins* | Limassol |

| Eli Kerr | Montreal |

| Fanta-MLN | Milan |

| Femtensesse | Oslo |

| François Ghebaly | Los Angeles/New York |

| Franz Kaka | Toronto |

| Gallery Vacancy | Shanghai |

| Gauli Zitter* | Brussels |

| General Expenses* | Mexico City |

| Gian Marco Casini | Livorno |

| Ginny on Frederick | London |

| Good Weather North | Little Rock/Chicago |

| Hot Wheels | Athens/London |

| Kai Matsumiya | New York |

| Kendall Koppe | Glasgow |

| Khoshbakht | Cologne |

| Kogo | Tartu |

| Lars Friedrich | Berlin |

| Laurel Gitlen | New York |

| Laveronica | Modica |

| Longtermhandstand* | Budapest |

| Lovay* | Geneva |

| Lucas Hirsch | Dusseldorf |

| Lungley | London |

| Madragoa | Lisbon |

| Margot Samel | New York |

| Martina Simeti | Milan |

| Matthew Brown | Los Angeles |

| murmurs* | Los Angeles |

| Nicoletti | London |

| Noah Klink | Berlin |

| Nova | Bangkok |

| Öktem Aykut | Istanbul |

| P21* | Seoul |

| Page (NYC)* | New York |

| palace enterprise | Copenhagen |

| Parallel Oaxaca | Oaxaca |

| Parliament | Paris |

| Petrine | Paris |

| philippzollinger | Zurich |

| Piedras | Buenos Aires |

| Piktogram | Warsaw |

| Polansky | Prague/Brno |

| Project Fulfill | Taipei |

| Rele* | Lagos |

| Rose Easton* | London |

| Schiefe Zähne | Berlin |

| Selma Feriani | Tunis |

| Seventeen | London |

| Shore | Vienna |

| Silke Lindner* | New York |

| sissi club* | Marseille |

| Sophie Tappeiner | Vienna |

| Sperling | Munich |

| suns.works | Zurich |

| Super Dakota | Brussels |

| Suprainfinit | Bucharest |

| Tabula Rasa | Beijing/London |

| Tara Downs* | New York |

| Temnikova & Kasela | Tallinn |

| The Ryder | Madrid |

| Theta | New York |

| Valeria Cetraro | Paris |

| Vanguard | Shanghai |

| VIN VIN | Vienna |

| Voloshyn | Kyiv/Miami |

| wanda | Warsaw |

| Wonnerth Dejaco* | Vienna |

| Wschód | Warsaw |

| Yutaka Kikutake* | Tokyo |

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

Hadiya Williams spent 20 years in the world of graphic design before discovering a full-force passion for clay. What began as an innocent hobby in 2017 turned into a full-time job when design studio Black Pepper Paperie Co. was established, with Williams as the founder and creative director. Based in Washington, DC, she now spends her days creating decorative art referred to as terrestrial and generative, ceramic objects, and surface designs.

It’s easy to see how Williams’ previous career and her current one are related through the graphic patterns and abstract creations that she favors. But her inspiration also comes from somewhere deeper: the connections between West African art, textiles, and the design styles of the mid-20th century Black Arts Movement and the early 20th century Harlem Renaissance. The resulting artistic creations represent cultural influences from across the Black Diaspora, connecting the distant past to today’s present and the future that’s to come. As Williams unites art, design, traditions, and stories through patterns and techniques, her gift is made clear to anyone paying attention.

Williams has had the opportunity to collaborate with various brands, including F. Schumacher Co., Target, Lulu and Georgia, WALPA (Japan), AARP, and Meta.

Today, Hadiya Williams joins us for Friday Five!

My love for thrifting and old objects runs deep, stemming from a childhood spent admiring my mother’s style and her things – the art, the textiles, the music, etc. Those early connections shaped my passion for design, and I’ve been an avid collector ever since. Thrifting isn’t just a hobby; it’s a way to travel through time and experience the past through tangible relics. Over the years, I’ve honed my style, drawing inspiration from classic design details that resonate with me. Each find tells a story, preserving a piece of history that continues to influence my creative work and the things I hold close to my heart.

Two of my favorites, visual artist Nakeya Brown and BLK MKT Vintage in Brooklyn, New York, do a wonderful job of collecting, capturing, and preserving Black Americana and nostalgia from a woman-centered perspective. Above is the piece, Going Down Makes Me Shiver, from Nakeya’s 2014 collection, If Nostalgia Were Colored Brown. It was one of the first pieces of art that I purchased, and it encompasses so much of what I love about art: material culture, design, music, and nostalgia.

Vintage chairs hold a special place in my heart; whether you collect them or craft them, they are a great way to express your design sensibilities. Over the years, I’ve developed a small collection of vintage chairs and seating, anticipating the day when I can showcase them in a space that does them justice. Among my recent favorites are Nicole Crowder Upholstery’s 8 x 8 A Line Collection, a contemporary reinterpretation of the classic 1963 Hans Wegner Shell chair. Inheriting eight original chairs in 2020, Nicole breathed new life into them through reupholstery, transforming them into one-of-a-kind pieces that each have a special story. This merging of classic craftsmanship with contemporary sensibilities and storytelling captures the sweet spot where I appreciate design the most.

Eaton Hotel-Wild Days DC, Mosaic by Zoe Charlton Photo: Courtesy of the Eaton Hotel

Lately, I’ve been talking about my desire to travel the world and stay in boutique hotels. I’ve always liked hotels, but there’s something special about boutique ones with their unique designs. I’ve stayed in a few over the years, and you can see how much effort the designers put into them. It’s a dream of mine to design a collection for a boutique hotel one day. Among the many I’ve visited, the Eaton Hotel in DC holds a special place in my heart. Since its opening in 2018, it has fostered a vibrant social culture centered around community, all while maintaining quality hospitality and timeless design. When a hotel can seamlessly blend the comforts of home with a sense of escape, it achieves perfection.

As a general advocate for sustainability, I hold a deep love for the enduring charm of paper books, quietly hoping they never fade into obscurity. While I enjoy my current fiction and non-fiction as audiobooks, my shelves are adorned with a plethora of art and design tomes. It’s practically a reflex for me to grab a new one whenever the opportunity presents itself, making sure that even when I travel, there’s enough space for a few books. The ones in this photo are a good representation of what inspires me and what kinds of books I gravitate toward. Each one offers a well of inspiration, from the tactile feel of the paper selection to the beautiful photography and art, the meticulous craftsmanship of layout design, and the varying dimensions that lend a unique character to each piece. Needless to say, paper holds a sacred place among my top five passions, with art books reigning supreme as the ultimate indulgence.

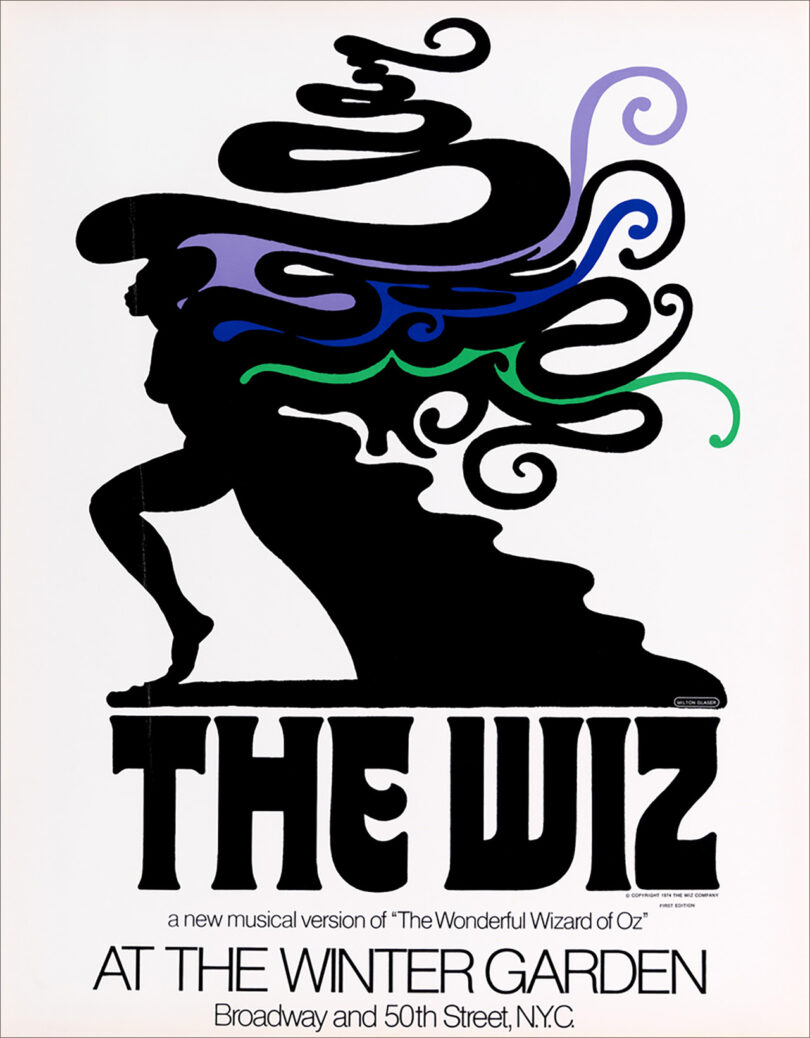

The Wiz, Milton Glaser, 1976; Lithograph on woven paper Photo: Courtesy of Cooper Hewitt

If I had to pick one era of music, it would undeniably be the 1970s. It holds a significant place in my heart, as it has shaped various aspects of my life. Being born towards the end of that decade, the memories of my childhood are deeply connected with its cultural influence, impacting everything from my creative work to my personal style and aesthetic preferences. The music of the 70s, particularly soul-centered genres like R&B, funk, jazz, afrobeat, disco, and Latin jazz, resonates with me profoundly. It has a timeless quality that transcends the confines of its era, resembling a form of Afro-futuristic sound. Moreover, the album art from this period stands out as some of the most exceptional in music history.

The 1976 The Wiz Broadway poster by Milton Glaser is featured because of this production’s overall impact on Black American culture, the music quality, the cover art, and because the play, film, and soundtracks are my absolute favorites. This universe holds all of the things that I’ve referenced throughout about certain objects and works of art traversing time and space.

Started in January 2023, the Ancestor Index (AI) is a visual archive of my ancestral venerations crafted in collaboration with MidJourney. Using my own handmade ceramic and surface pattern work to generate these one-of-a-kind images, they pay homage to my ancestors, Black women and girls, and the movements of the Great Migration. Using my own handmade ceramic and surface pattern work to generate these one-of-a-kind images that pay homage to my ancestors, Black women and girls, and the movements of the Great Migration.

This is part of my 2024 limited edition collection in collaboration with sustainable baby and lifestyle brand Esembly Baby.

My 2023 Collection with Lulu and Georgia includes wall art, decorative pillows, and table linens.

Hand-built stoneware mugs made for F. Schumacher Co. Nashville, 2024.

My 2020 wallpaper collection in collaboration with WallPops Peel-n-Stick wallpaper.

This post contains affiliate links, so if you make a purchase from an affiliate link, we earn a commission. Thanks for supporting Design Milk!

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

Lynn Welker’s abstract paintings are spare sanctuaries in a disorderly world. By Michael Gormley Lynn Welker’s semi-abstract inventions, created using a direct-painting plus collage technique, reference Pablo Picasso’s and George Braque’s early cubist experiments. Welker, who attended the University of Cincinnati College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning in the mid-’60s, notes, “Picasso was very…

The post Moods of Nature appeared first on Artists Network.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

A new security law amending Hong Kong’s basic law (its mini-constitution) was passed yesterday and will be implemented from 23 March. The law has cast a pall over the city’s bustling art week, as well as a full-sized Art Basel Hong Kong (26-30 March) that had been excitedly billed as a return to pre-pandemic form.

Passed unanimously by the 89-member “patriots only” legislature known as Legco, the article 23 measure is a local follow-up to the June 2020 national security law imposed by mainland China. It was first introduced in 2003 but shelved that year after triggering the first of three mass protest movements that have since taken place in the city.

Backers and opponents alike say article 23 simply reinforces extended policies that have clamped down on resistance against Hong Kong’s Beijing-controlled government, and that its impact will depend on actual implementation. Both sides draw comparisons to America’s draconian 2001 Patriot Act following 9/11, which gave intelligence agencies and law enforcement dramatically increased powers of surveillance and other counter-terrorism measures.

“The pendulum has been swinging one way: it keeps tightening,” says a Hong Kong-based curator, speaking anonymously. “There have been pauses along the way. Will there be another one? Will it tilt back a bit more?”. Some “contemporary art won't be affected," he says: “abstract art, for example, they don't care. But the space for the broader relevance of art is tightening and closing down.” He adds, however, that “the government propaganda isn't fooling anyone, locals or foreigners. It's almost like the propaganda now isn't aimed at convincing people, it's so weird.”

“At this stage we have no indication that Article 23 will have any impact on the way we operate,” says an Art Basel Hong Kong spokesperson. “We have never faced any censorship issues at our shows, nor have we been asked to do anything differently since the introduction of the national security law in 2020. As with all Art Basel shows, our selection committee is responsible for reviewing applications and selects galleries solely based on the quality of their booth proposal."

The spokesperson continues: “We are committed to Hong Kong's vibrant cultural community, and to continuing to provide a platform for the vital exchanges and conversations around art for which Art Basel is renowned."

The 212-page measure, which Hong Kong’s chief executive John Lee has heralded as “historic”, introduces 39 new kinds of security crimes. It stipulates life sentences for sabotage, treason and insurrection, five to seven years for theft of state secrets and espionage, and up to ten years imprisonment for collusion with “external forces”. (The government has made a concerted effort to reframe the 2019 protests, which were sparked by an unpopular extradition bill, as a “colour revolution” and “black riots” instigated by foreign powers.)

Also under the new law, failure to disclose the “commission of treason“ by others brings 14 years’ imprisonment. Organisations such as the Hong Kong Bar Association and Hong Kong Journalists Association have expressed concern about the broad, vague definitions of the infractions.

Two Hong Kong-based artists anonymously describe the measure as expected after earlier crackdowns. “It feels inevitable, like many decisions here since 2019,” says one who is preparing to leave the city next year. “The sensation has been that there's nothing to be done, that meaningful decisions were never really in the hands of people here and any appearance of local influence was merely for optics.”

“No one actually talked about [Article 23] yesterday,” says the other. “It feels like something you know will eventually happen and you could not stop but you can ignore it. And we avoid talking about it as if this is not important.”

The first artist adds: “People in the industry have been working very well within the confines, the many unknowns and red lines. Due to the lack of space here because of the high cost of living, and the resulting family/social pressures required to adapt to living in one of the world's smallest amount of personal space per capita, Hong Kong is more a market than a place of artistic production. The market has and will adapt to these new conditions.”

The same artist believes Article 23 will further accelerate the ongoing cultural brain drain. “Hong Kong artists like many middle class Hongkongers [historically] go overseas for education, often obtain passports or residency abroad, and return to the city if conditions are positive here. Since 2019 they do not return. Every practicing Hong Kong contemporary artist I know has or is working on a plan to leave.”

The curator says that implementation is the key question. “It's true that a lot of such regulations and laws exist in other countries. How they are applied is completely different.“ He adds that “already [here] they will catch you with NSL [national security law].” He says that while the tough law and now article 23 have “eviscerated the official opposition, plus clamped down the space for freedom of expression in Hong Kong”, the bigger, often overlooked worries “are quieter trends that people (including the media) aren't paying attention to.” These are “the climate of fear that people—or more specifically organisations and funders—feel is really causing issues in the non-profit sector.”

A push across the board to minimise risk when providing funding for the arts, meanwhile, means a “systematic vetting of artists for even minor risks, and often choosing or pressuring organisations not to do an event,” the curator says.

“And again, they are taking not just the mainland [China] playbook but the Singapore playbook,” where systematic visits to check for infractions under the auspices of health and safety are commonplace. “They just grind you down like that with official-looking visits and checks.”

Though the city’s scene has until now nurtured an exciting generation of young artists, “for emerging artists, would they still be interested in developing art that [encourages] challenging thoughts?” wonders the second artist. “Or would they simply create decorative and positive art works in the future? Hong Kong is part of China so it is never too late for Hong Kong artists to learn from artists in [mainland] China,” be that through evading or complying to censorship.

She posits that the measure will not impact Hong Kong’s art week or art market. “Parties still go on. No one wants to talk about serious and heavy topics when they want to make a living, especially with the people with power and status and money, people who are with the same class of the rulers.” Instead of more political engaged art, “Hong Kong’s art world is moving forward towards the funding bodies’ interests like art tech, celebration, and spectacles for tourists.”

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

The first-ever underwater inquiry into the far-flung Greek island of Kasos concluded after four years last October—and the results are in.

The Greek Ministry of Culture has announced that an international, interdisciplinary team of researchers documented 10 total shipwrecks dating from 3,000 B.C.E. through last century at depths of 20 to 47 meters. Although it appears that none of the vessels were brought back to land, researchers did snap 20,000 underwater photos to further explore their remains. In addition to generating such materials for future study, the project aimed to emphasize that locals working with the waters, such as fishermen and divers, participate in the long history of Kasos’s seas.

A diver documenting archeological remains. Courtesy of the Greek Ministry of Culture

Accounts of Kasos from Homer’s Iliad guided the team’s search. This southernmost island in the Dodecanese complex totals 49 square kilometers, characterized mostly by stony mountains and beaches. Seafaring Phoenician merchants sought shelter here, and Homer noted that Kasos contributed ships to the Trojan War.

“The middle of the Island is almost a plain, well planted with Olive trees, and Vine-yards; with all sorts of Fruits,” English merchant Bernard Randolph wrote in 1687. In the 18th century, French naturalist Charles Sigisbert Sonnini added that the wine and honey produced on Kasos are legendary.

A diver exploring the sea. Courtesy of the Greek Ministry of Culture

The Kasos Maritime Archaeological Project’s website highlights the range of researchers involved in this collaborative project, organized by the National Hellenic Research Foundation (NHRF) and the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities (EUA)—including archaeologists, conservators, engineers, surveyors, geologists, commercial divers, heritage managers, and historians.

Researchers take notes underwater. Courtesy of the Greek Ministry of Culture

By 2021, that team’s “innovative and spherical approach” had turned up an ancient Roman shipwreck loaded with ceramic amphorae crafted in Spain and Tunisia that were once filled with oil, alongside 1st-century and 5th-century B.C.E shipwrecks and a modern boat made of wood and metal which was most likely sunk during World War II.

New additions from this week’s announcement include ancient ships bearing merchandise from Spain, Italy, Africa, and the coast of Asia Minor, the Greek Ministry of Culture reported, along with “important individual findings” such as a stone anchor hailing from the Archaic period and terra sigillata drinking vessels of African origin, from Roman times. Researchers also created the first-ever map of the Kasos-Karpathos reef and the Carpatholimnionas area using lateral scanning sonar.

Researchers gently brush off a finding. Courtesy of the Greek Ministry of Culture

What’s more, the years of research have yielded an 11-minute documentary produced by AORI FILMS titled Diving in the History of the Aegean, which has been selected to compete at global archeological film gatherings like the Archaeology Channel International Film Festival in America and Firenze Archeofilm Festival in Italy.

And their work’s still not done. Next, researchers will analyze their findings alongside further context from historians, archaeologists, and conservators—and publish a full report through the National Research Foundation later this year. June will initiated a similar exploration into the sea around the nearby island of Karpathos.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

Billy Porter is known for going big. The 54-year-old actor and singer routinely stole scenes as the drag ball emcee Pray Tell in FX’s drama Pose, a role that won him an Emmy. In Amazon’s 2021 update of Cinderella, he turned the fairy godmother into a fabulous, tough-talking fairy “godmuvva”, as he puts it. But his latest role, in the Bill Oliver-directed relationship drama Our Son, takes a different tack: as Gabriel, a relatively meek stay-at-home dad divorcing his husband, Nicky, (Luke Evans), Porter is required to play small, wounded and, sometimes, bitter, without any of the glitz or glam of his best known characters.

It’s the kind of role that Porter always knew he could pull off, but has rarely been considered for. Even fans, he says, don’t really get it. “At the premiere, somebody said to me, ‘Oh my God, Billy, how do you act like that?’” he recalls. “Would you ask Viola Davis that question? Would you ask Al Pacino that question? The world has a difficult time understanding that fabulous and serious do coexist – and you’re looking at him.”

In case you were wondering, yes – this is basically how Porter speaks 100% of the time. Over the course of our 45-minute interview, he compares himself with the four-time Oscar nominee Viola Davis on three separate occasions; he punctuates his musings on a ceasefire in the Middle East with the word “doll”. Peering out from Zoom in a hotel room in Florida, dressed (relatively) casually in a white T-shirt with sparkly rainbow accents, he comes across as a born orator, delivering every response as if he’s playing to the cheap seats in an auditorium. His charisma, which made him a star on TV and on Broadway, is on full display.

Our Son, though, is the first time Porter has been able to properly flex his dramatic chops on screen. Preparing for the role, he says, was relatively easy. “I could connect to the complexities of what it is to be in a marriage,” he says. Although relatively circumspect about details of his personal life during our conversation – particularly because his mother died only a week before – he does reveal that working on Our Son ended with a case of life imitating art. “I was married at the time, and I am no longer, and I knew in the filming of this movie that I probably wouldn’t be married after it was done,” he says. There is one way, of course, that his divorce, from his husband of six years, Adam Smith, felt “vastly different” from that of Gabriel and Nicky: “It’s not amicable – that’s all I can say.”

Gabriel is the kind of complex queer character that Porter dreamed of playing when he was struggling to make it as an actor in the 1990s. Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, he graduated from Carnegie Mellon University’s College of Fine Arts in the early 90s and moved to New York shortly afterwards. He soon found that complex roles for Black performers were few and far between; his big break was as the Teen Angel in the 1994 Broadway revival of Grease – hardly the multifaceted opportunity he had hoped for. “I was wearing 14 inches of orange rubber hair on my head and prancing around like a Little Richard automaton on crack,” he recalls. “I was a clown.”

He soon realised that he had to “shift the consciousness of the people” in order to find work that he felt was meaningful – and that would involve hard work on his part. He saw Viola Davis – “a friend of mine, not close … colleague … we’ve worked together … we know each other,” he says before mentioning her name, seemingly unsure of how to classify their relationship – as an example of how a serious Black performer could make it in the suffocating Hollywood system.

“She played every crack mother, every mother of a drug addict, every stereotypical dark-skinned Black woman role they threw at her, and she imbued those characters with dignity. I was like, ‘That’s what I’m gonna do,’” he says. He decided that he “didn’t care about being pigeonholed in the business”, and that he would “take the queer roles and imbue them with so much dignity” that by the time the industry was ready to give a serious, nuanced role to a Black gay man, he would be “the bitch that you call”.

At this point, Porter has been working in entertainment for more than 30 years, and has had a front-row seat to the seismic shifts that have taken place as the industry has reoriented itself around streaming. During last year’s Screen Actors Guild (Sag) strike, he was an outspoken critic of studio chiefs such as Disney’s Bob Iger, who suggested that striking workers’ demands were unreasonable; he also revealed that the instability resulting from the strike meant that he was putting his house on the market, for fear of no longer being able to afford it. A few months removed from the resolution of the strike, he feels like Sag and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) “came to some really good terms”, but he’s still miffed that “the burden and the fallout still gets passed on to us, and not the people in the C-suite”.

“Our deals are going away, our jobs are going away, everyone’s downsizing, but the people in the C-suite are still making [money],” he says. He’s still frustrated that there’s no accountability for “the people who ran the business into the ground”. “Whose fault is it that the business can’t sustain itself and is going to implode?” he asks, his eyes steely behind thick-rimmed glasses. “Streaming destroyed the artist’s ability to make money, our ability to participate in capitalism. Being an artist, we’re always freelance, and very often blue collar.”

That it took so long for the streamers to renegotiate terms with Sag-Aftra, Porter says, has resulted in a shrinking middle class of working actors. “Those Friends people are making $100m a year!” he exclaims. “I’m getting six-cent cheques! It’s not OK!”

Even so, Porter describes himself as one of the “extremely blessed ones” who is able to generate income through other means – “I’m a person who is so multi-faceted – I have a brand new pop album out, honey, on Republic records. I can go back to do a Broadway show, you know what I mean?” – but he makes it clear that he’s still very much a working actor. “People have this perception that we’re millionaires. You know how much I made on Cinderella? Only enough to cover my mortgage for four months, maybe,” he says. “It’s unacceptable that I’m one award away from an Egot (he has won an Emmy, Grammy and a Tony, but not an Oscar) and one strike puts me out of my house.”

Porter is, indeed, an impressive multi-hyphenate: in addition to acting and singing, he also made his directorial debut in 2022 with the Amazon Prime teen film Anything’s Possible, about a transgender high-school student. In his early-30s, a period of his career when “the work dried up”, he took a screenwriting course at the University of California in Los Angeles; now, he’s putting those skills to work, co-writing a biopic based on the life of the revolutionary writer and activist James Baldwin, in which he will also star. His motivation is simple: “If not me, who? I’ve been sitting around waiting for people to tell the Langston Hughes story, the James Baldwin story – anyone Black and queer, as far as I’m concerned. I’m done waiting – I’ll do it myself. The audacity, right?” he says. “Who’s going to tell it better than the Black gay man who embodies that in today’s age? It’s such an important story to tell, and I feel so blessed to be in this time where it will get told.”

Porter says that Baldwin’s story “couldn’t have been told before this time because nobody gave a fuck”, but that executives are wiser, now, to the fact that stories catering to marginalised audiences can be hugely lucrative. “If there’s green [money] attached to it, executives will care, and that’s always across the board,” he says. As often becomes clear during our conversation, Porter seems to have thought this concept through in his head, in a way that doesn’t necessarily translate out loud. He says: “How do we, on this end, acknowledge that the colour is green? It’s not black, it’s not white, it’s not yellow, it’s not Muslim – the colour is green.”

He has been inspired to see Greta Gerwig – his co-star in the 2014 film adaptation of the Philip Roth novel The Humbling, “before anybody knew her” – push a female-oriented film like Barbie to box office success in the way he hopes to with Black queer stories. “Barbie is green – [Gerwig] got all the fucking green; she can do whatever she wants, because they want that,” he says. “I’m trying to figure out for myself what that looks like, because we have to understand, too, it’s a business – it is show business, and business is the bigger word. We cannot lose sight of that.”

Porter describes his Baldwin biopic as “sprawling”, and says that a piece of the novelist’s writing will be used as a framing device through which to explore his whole life. Baldwin, of course, was a strong advocate for the rights of Palestinians; Porter has been staunchly supportive of Israel in the past, opposing the cultural boycott of a film festival in Tel Aviv in 2021, and he was one of 700 celebrities who signed an open letter last year asking Hollywood to support Israel in its retaliation against Gaza after Hamas’s attack on 7 October.

When I ask Porter how he plans to navigate Baldwin’s relationship with the Palestinian rights movement in the script, given his own support of Israel, he quickly clarifies his position. “First and foremost, I’m supportive of a two-state solution. The second thing is, this is not my hill, and I am not going to die on it. It’s not mine! I’m not Jewish, nor am I Palestinian,” he says. “What’s going on over there is horrific – the choices that we, in America, have made, are wrong. Please don’t make me a poster child for that. I don’t want to be in the conversation, because I don’t know enough about it!

“I am in support of my Jewish friends and my Palestinian friends,” he says. “It’s a two-state solution that’s been going on for thousands of years over there. I don’t know!” he says, letting out a nervous giggle. “What I do know is that we don’t need to continue to be bombing over there. I know we should stop doing that, I do believe that. And the Palestinians – not Palestinians, what are the people called, who started the shit? The extremists?”

Hamas?

“Thank you! See, I don’t even know. All I know is that the extremists came in and did something that was horrific, and then they retaliated,” he says. “Now, the retaliation is a little overkill, now, doll. But why are we at war at all? That’s not just about them, that’s everywhere. We’re always at war. It breaks my heart. I don’t know what to say, and I don’t know what to do, other than hug you and say I’m sorry, and what can we do to fix it? I’m in support of peace! Fucking peace!”

At this point, Porter is the most worked up he’s been through our conversation – but in a split-second, he’s composed himself. “There’s nothing to navigate – I’m not James Baldwin, he’s a character, so I have to be true to the character. I don’t know what he was talking about in the 40s, 50s, 60s – it’s 2024 now. I don’t have the history to even know what the version of the Israel-Palestine conflict was when he was around,” he says. “It’s not a part of the script – his civil rights work in America is what we’re focused on, more than what he thought about the crisis in the Middle East.”

Our time is up, and Porter thanks me for asking the question, noting that his Instagram comments have been filled with people writing “Free Palestine”. “I’ve been getting a lot of bullshit online about it – I’m like, ‘I don’t know, y’all!’ The man’s been dead since 1987, please!” he says. As ever, it’s a big exit.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

Karachi-born conceptual artist Rasheed Araeen’s Islam and Modernism encourages Muslim artists and scholars to learn from the Islamic history of ideas pertaining to modernity in lieu of a Eurocentric discourse. The London-based author juggles philosophy, religion, a short critique of Hegelian aesthetics, and abstract art under one title, taking only the so-called “Arab world” as a reference point of Islamic scholarship and art. As a result, the book is a timely and necessary, but also a puzzling and cluttered read.

An engineer by education, Araeen is one of the pioneers of minimalism in Britain and co-founder of the art journal Third Text. His geometric sculpture and painting from the 1960s to ’80s brought prominence to the presence of Pakistani diasporic artists largely made invisible by the British art scene. Western art critics of the time could not reconcile his expressions of identity as a Muslim, Pakistani artist interested in minimal, geometric art. He has since been highly critical of Western scholarship that ignores Islam’s spiritual and philosophical ethos, which has influenced modern art created across Islamic cultures.

Araeen concisely turns to formidable Islamic scholarship on modernity, such as works by Indian poet and philosopher Muhammad Iqbal, Swiss writer Titus Burckhardt, and verses from the Qur’an, instead of Eurocentric literature dominated by Christian authors. He writes, “The main issue is Eurocentric modernism and its history, which can be dealt with by redefining modernism and re-writing its history. How can this be achieved when Eurocentric modernism is persistent in its domination of the art world with all its institutions”?

He suggests rectifying this problem in two ways. First, missing gaps in Islamic philosophy and history of knowledge that arise because of deliberate or unconscious ignorance must be addressed by contemporary scholars and practitioners. Secondly, institutions that promote research “liberating” art from Muslim regions from its “subservience to the West” must be established. As an example of the latter, he mentions the Sharjah Biennial in the United Arab Emirates. Araeen cites the case of the influential Pakistani Modern artist Anwar Jalal Shemza, who began to work in Britain in the late ’50s within an art scene that maintained an incompatibility between modernism and the works of non-Western artists influenced by Islamic scripture.

Problems in the text arise when Araeen does not consider the nuances of identity that may not depend on personal religious beliefs. Moreover, in framing West Asia and North Africa as the harbinger of Islam, he does not take other Muslim art traditions into account, especially those of South Asia and West Africa. The complex histories of Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh, which comprise multiple religious identities and historical literatures, are largely absent from the book. Further, to consider only Islamic scholarship in one geographic area is to inevitably isolate Buddhist, Hindu, Jain, and other interlinked intellectual lineages informing one another and co-existing in the same region for millennia.

Islam and Modernism is a readable, provocative polemic deliberating on the present philosophical and aesthetic crises in art from the Islamic world. Though teeming with opportunities for further scholarship, its arguments fail to blossom as an in-depth study. Our first qualm to resolve must be the exclusion of art from “non-Arab” Muslim communities. Assessing the relevance of Eurocentric modernist studies for non-Western art can then follow.

Islam and Modernism by Rasheed Araeen (2022) is published by Grosvenor Gallery and available online.

[ad_2]

Source link