Photo David Heald/©Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York. Copyright: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York. All rights reserved.

[ad_1]

There’s a brief moment at just about the midpoint of HBO’s adaptation of “The Sympathizer” when the show’s recurring flaw really settles in. Its fourth episode chronicles the filming of a movie within the story. Like in the miniseries’ source material — Viet Thanh Nguyen’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel of the same name — this fictional Hollywood production bears a strong resemblance to Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 Vietnam War epic, “Apocalypse Now.” The novel and series’ unnamed protagonist is an adviser on the movie, directed by a volatile white male filmmaker simply called the Auteur.

Ostensibly, our protagonist — known to most people around him as an ex-captain in the South Vietnamese army, now living in the U.S. as a refugee — is there to make sure that the film and its portrayals of Vietnamese characters are culturally sensitive. But at best, he’s really there to try to temper anything super racist. (And for the most part, his attempts at course correction are utterly futile.)

The episode departs from the book in several ways, including when someone places a deer’s bloody head in another person’s bed. It’s a clear nod to “The Godfather” — and a bit too on the nose.

That lack of subtlety and taking a reference one step too far sum up the most frustrating shortcoming of the seven-episode limited series, which premieres Sunday night. Adapted by Park Chan-wook and Don McKellar, the show on its own is a stylish, impressively shot and well-acted spy thriller following the travails of the protagonist, who is secretly a communist agent.

But crucially, the series loses the heft of the book, sanding down its sharp edges. Elements of its mordant satire don’t cut through, and the novel’s searing commentary on who gets to tell stories about war and how they’re too often flattened is largely forgotten, only really explored in that one episode.

To put it more bluntly, the book understands that the audience is smart. The series, however, seems to think that we can’t be trusted to piece everything together ourselves.

Visually, it’s hard not to be immediately drawn in by the show’s auteurist touches. Each episode opens with the familiar HBO static logo — but in a preview of what’s to come stylistically, the shot zooms in on the “O” to form part of a scrolling film reel. There’s a wealth of visual references to movies of the 1970s, including not only Coppola’s films but also Martin Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver.”

As the protagonist, referred to only as the Captain, Hoa Xuande — best known for a recurring role on Netflix’s live-action “Cowboy Bebop” series — carries the show as its breakout star. Around him, there’s a wonderful ensemble of supporting players, including Toan Le as his boss, the General; Fred Nguyen Khan as his childhood friend Bon; and Vy Le as Lana, the General’s daughter. Familiar faces also pop in and out of the series, like Sandra Oh, who is fantastic as always. And you might do the “Leo pointing” meme upon seeing the actors who appear in the movie within the show, adding to the meta quality of that storyline.

Then there’s the Robert Downey Jr. of it all. Much of the advertising for the series has highlighted the fact that the newly minted Oscar winner portrays multiple roles: several of the white men in the protagonist’s life, including a CIA agent and ally of the General; a racist and mansplaining “Oriental studies” professor; and a Republican congressman whose main campaign pitch involves pandering to the Vietnamese refugee community by touting his opposition to communism. Downey’s truly gonzo performance is a fun commentary on the interchangeability of these white men, all of whom represent the colonizer in various forms.

On a practical and mercenary level, his star power likely helped the series get made. (He also serves as an executive producer.) But after a few episodes, his stunt casting becomes distracting and even a bit grating.

That kind of maximalism hampers the series at every turn. Just when you’ve gotten the point, the show hits it again, in case it wasn’t clear the first time. Much of the book concerns all of the ways that the protagonist is grappling with dual identities in his life and how he never quite fits in anywhere. He’s the biracial “bastard” child of a Vietnamese woman and a French priest. He’s on both sides of the Vietnam War simultaneously, embraced by the American political establishment as an anticommunist fighter while secretly sending information back to a childhood best friend named Man, a communist operative.

Upon arriving in America as a refugee, he struggles with feeling not Vietnamese enough but not quite American either. All of those representations of duality are inherent to the book. But in the series, they’re often spelled out with too heavy a hand.

Maybe it’s a cliché to say this about an acclaimed novel, but so much of what makes the book a page turner is the text itself. This is especially true of the novel’s interiority, which is hard to capture on-screen without being blunt in the dialogue and visual cues. And so much of the book is about the written word. Case in point: The framing device of both the book and the series is a written confession from the protagonist, which can be clunkier to convey visually than on the page.

This isn’t the place to rehash the perennial question of whether certain books are unadaptable. Books and their screen versions have different reasons for existing. There are so many ways to approach the adaptation process that don’t fall into a simple binary of remaining faithful to the original material or not.

One central argument for this series is visibility: More people are likely going to encounter the story of “The Sympathizer” through the HBO show than the novel. And in our age of Hollywood conglomerates regurgitating existing IP and trying to squeeze every drop out of lemons that went dry long ago, it’s undoubtedly more creatively fresh to adapt a groundbreaking novel from an acclaimed Asian American author than to, say, reboot an old franchise and shoehorn in some surface-level diversity.

At the same time, it’s disappointing when the result strips away a lot of what makes the source material distinctive. There’s a biting irony in an adaptation of Nguyen’s book — a novel about how the stories we collectively tell about wars are far more complicated than two sides, and how they routinely get watered-down — being itself watered-down. But that’s Hollywood for you.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

For over a decade, Kathleen Herles voiced one of the most iconic kids characters in history: Dora Márquez aka Dora the Explorer.

She was cast at the age of 7 and worked on the pilot for over a year. Initially, the show wasn’t picked up, and Herles was 10 years old by the time it premiered in August 2000. “Dora the Explorer” aired for eight seasons until August 2019 and featured the title character with her backpack and best friend Boots as they completed epic adventures.

A first-generation Peruvian American, Herles says voice acting was a huge learning experience for her and her parents, who emigrated from Peru in their late teens. While Herles had an inkling that the show might be a success, she never could have predicted the generation-wide impact she’d have on kids her age.

“I’m like the best babysitter of all time,” Herles jokes during our virtual interview.

Dora’s impact and the global success of the show can’t be ignored. Paramount+ is ready to introduce Dora to a new young audience, with its revival series, “Dora,” which premieres on Friday. Diana Zermeno is the new voice of Dora. Herles voices Dora’s mother, Mami, in a full-circle moment. She notes that there will be tons of differences in the upcoming reboot, but also tons of similarities.

“I think people who are my age, who grew up with [Dora] will still feel that sense of nostalgia, but it will also be something that this new generation will also connect with,” she says. “And the new voice of Dora, I remember when I first heard her, literal tears came to my eyes. I know she’s going to lead this new generation to what they need.”

To say the show changed Herles’ life is an understatement. She went from a full-time elementary student to recording lines for a TV show, toys, video games, and more.

So how did a 7-year-old come up with the voice that would define a generation? It turns out that was just how Herles sounded when she was younger. Nowadays her voice is a little deeper, but she easily slips into the voice of Dora with its unique high-pitch inflections and playful candor.

While she remembers being directed in the booth as a child, Herles says she tried to just have fun with it.

“You don’t put a lot of pressure on yourself when you’re a kid. You can play and you can make very natural decisions in your acting. I think that’s what’s really special about a child actor. You just feel a little more free,” Herles says. She tries to maintain this youthfulness as she pursues voice acting full-time after quitting her job as an interior designer last June.

“I want to make sure I don’t lose that playfulness — that’s what makes animation fun for everyone,” she said.

Beyond making a show that resonated with children and allowed them to learn more about a different culture and language, Dora was a historic turning point for kids entertainment. Not only was it almost revolutionary to have a Latina that openly speaks Spanish as the main character on a children’s TV show, but Herles was one of the few Latinas in the industry paving the way for other voice actors of color. As of 2021, only 16.5% of voice actors identify as Hispanic or Latino, and with women making up only 29.2% of the total voice acting world, that makes Latina voices an even rarer phenomenon, especially in the early 2000s.

During her time on the series, Herles says there was still a lot of stigma surrounding what a Latino should sound like. She remembers many people expecting to hear an accent or wanting her to feign an accent to seem more Latino. While this may seem like a minute detail for non-Latinos, it’s an incredibly dividing topic within our own communities. There’s stigma for those without accents because you’re not considered Latin enough, and there’s stigma for those with accents because you don’t sound American enough.

Herles says this was an issue in her own household. She was taught English first so that she’d have a more neutral accent and not encounter any comprehension issues in school — something her older brother struggled with.

Growing up, Herles struggled with wondering if she was Latina enough because her Spanish wasn’t perfect, and she didn’t have an accent like her brother or parents. Despite her own questions regarding her identity, Herles says it’s vital to not be type-casted as a Latina voice actor.

“I think even today it’s kind of hard for me to understand what the expectation is from me because I don’t see myself any less Latina or any less Peruvian because my Spanish isn’t perfect or has a specific accent attached to it,” she says. “We’re all different. I’m still Latina and nothing can take that away from me. This is where I come from and no matter how I speak, how I act, that’s never going to change. And that’s me.”

Beyond finding her own voice through Dora, Herles believes Dora paved the way for children’s programming and animation. She says it was not only an introduction into a new culture for many children, but a huge win for Latino representation during this time.

“I’ve heard so many times people saying [they] had no one to connect to until Dora,” she says. “I think that’s where you can see the importance of representation as a whole.”

For Herles herself, Dora was a doorway into the impossible. Her favorite episode to record was “Dora’s Fairytale Adventure” where Dora becomes a princess.

“I feel like a lot of girls dream of being a princess. For me, that was something I always loved, so when I got to do this episode, it really touched me in a different way. I didn’t know [being a princess] was possible because a lot of [them] didn’t look like me. Even as an actor, I didn’t know those were roles I could even play,” Herles says as she pulls out the toy version of Princess Dora and plays with the magically growing hair. “Dora’s bringing everybody together and keeping the door open to new experiences, to new adventures. That’s where her heart is, and it shows that’s how far she went.”

Despite having over 20 years of voice-acting experience, Herles says she still experiences imposter syndrome, even after she earned an Imagen Award nomination in 2007, and two NAACP Image Award nominations in 2007 and 2008.

She remembers being nominated in the same category as America Ferrera, Eva Longoria and Raven-Symoné, and feeling like she didn’t belong. Even now, when she’s attending conventions and waiting in the green room with other actors, she says she’ll look around and wonder if she’s meant to be there among the seasoned, beloved creatives.

“I feel like I have a community now within the industry, which I don’t think I had growing up. Having that support in the industry is really important, and I feel like that’s shaping who I am today. It makes me more confident and it pushes me to be better,” Herles says of finally feeling like she belongs in these spaces. “It’s always important to have that support and community in whatever you’re doing.”

While she says she struggled to see the impact her voice had in the past, she gets emotional thinking about Dora’s legacy now that she’s older.

“Dora will always be a part of me. She had such a big impact on my childhood and who I am, and who I was, that I don’t have to define myself without her. It makes me emotional to think about the impact, the importance [of Dora], and to be a part of something like that reminds me that my voice, as little as I may think it is, sometimes it’s a lot bigger.”

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

From the April 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

I’m in Paris, watching as a parade of Orientalist paintings appear, move then vanish from the walls of what was once a steel foundry. There are shisha smokers, belly dancers, and noble-looking men riding camels or battling lions – or, in the case of The Lion Hunt (1836) by Horace Vernet, doing both at once. This is ‘The Orientalists: Ingres, Delacroix, Gérôme’, the latest exhibition at Atelier des Lumières, a ‘digital art centre’ in the 11th arrondissement. On the floor are enormous projections of patterned rugs, while on the walls the paintings are surrounded by decorations. These are based on mashrabiya, the wooden latticework common in Arabic vernacular architecture, or on calligraphic metalwork, or on Iznik pottery. The designs turn like fast-moving cogs around the paintings as they come and go. Images that embody 19th-century European fantasies of harem life float through the space, while ‘It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World’ by James Brown plays.

Anyone passing through a major city in recent years is certain to have encountered signs of this phenomenon. Bus stops, billboards and underground stations advertise ‘immersive art’ exhibits that range from glorified ball pits (the Balloon Museum, London) to projections of paintings by Van Gogh (pick your city). Their offerings are aimed at a general audience and are a particular favourite of young families and those after an eye-catching selfie backdrop. What happens to our engagement with a painting when it is experienced in this way? How does being enlarged, made to move and given a soundtrack affect the way we see a work?

At the Atelier des Lumières, the best-known painting is undoubtedly the Grande Odalisque (1814) by Ingres. The differences between seeing the projection and the original are telling. Here, this languorous nude is given the special honour of filling one of the venue’s giant walls, her long, pale flank expanded to the size of a car. As animated curtains draw aside to reveal her nakedness, I find myself awed by the scale of the thing and interested in the reactions of my fellow visitors – yet before I have time to look closer, the show has moved on.

It is a different story in the Louvre, where the painting hangs. Visitors will find Ingres’s famous concubine at the end of a gallery that features work by the artist alongside contemporaries such as David, Géricault and Delacroix. In person, I’m surprised to notice details that had escaped me at scale: the white lump of opium in her pipe, the fine tendrils of smoke uncoiling from the incense burner, the texture of a fur.

I see afresh the anatomical inaccuracy – that overlong spine so vilified by Ingres’ critics – and the stoned aloofness in her gaze. Is there a trace of stifled resentment, or is she merely neutral? I visit other rooms where I discover the evolution of the artist’s treatment of the topic. I see another study of a long, smooth back in his earlier The Valpinçon Bather (1808) and feel mildly embarrassed by the soft porn stylings of The Turkish Bath (1862). Back at the Grande Odalisque, I notice the fine crazing across its surface; the actual object is vulnerable. Though perhaps that’s an upside to projection-based art shows: no travel-induced deterioration.

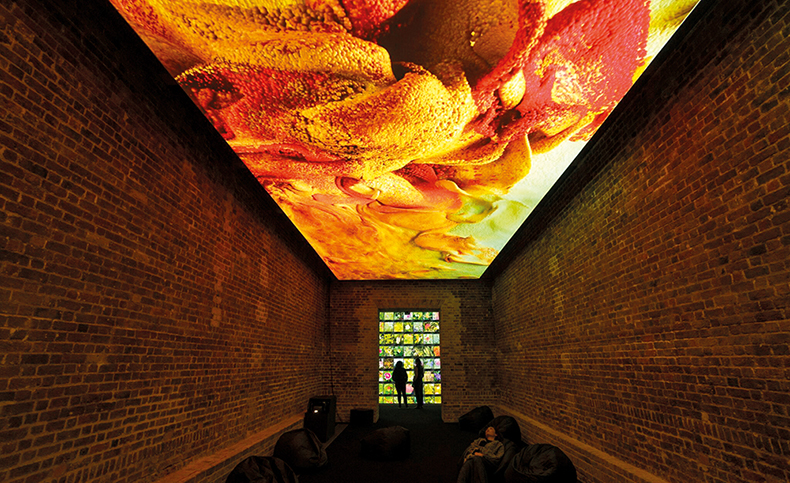

Atelier des Lumières’s display of Grande Odalisque (1814) by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. © Culturespaces/C. de la Motte Rouge

Right now, immersive options for the more artistically inclined visitor include ‘Leonardo da Vinci – 500 Years of Genius’ in Melbourne; ‘Monet: The Immersive Experience’ in Washington, D.C. and New Orleans; and ‘Van Gogh: The Immersive Experience’ in cities including London, Seoul, Milan, Atlanta and Tulsa. Each of these shows consists of digital animations of paintings projected across walls, ceilings and floors, usually in conjunction with sound, where swelling orchestral scores predominate.

It is unsurprising that Van Gogh appears so often in such settings. Celebrity aside, his roiling brushwork lends itself to animation to a greater degree than, say, Ingres’s far smoother application of paint. Van Gogh’s starry night skies swirl their way most effectively across the warehouse-like spaces that host these shows. There are some obvious advantages to experiencing artworks in this way. Masterpieces unlikely to be loaned to exhibitions touring regional cities can be seen all in one place. It is possible to enjoy (reproductions of) works that are usually inaccessible in private collections. Children appear more engaged than they do by a static work – it’s easy to imagine a visit planting a seed of artistic interest in a young mind.

There are downsides too, of course. The near-ceaseless movement can make close looking difficult; the eye is guided not by independent interest but by the animator’s choices; authorial intent is not respected (if one believes this matters); works are presented for maximum impact, with minimal context. This latter point becomes acute when the source material requires a nuanced understanding.

Even allowing for imperfect translation, the webpage for Atelier des Lumières’s latest show gives a flavour of the muddled art history at play: ‘Delacroix, Gérôme and Ingres, and other major names from European Expressionism, now invite you to embark on a pictorial expedition to the new, exotic and bewitching world of the Orient of our dreams.’ Without any interpretation in the space, everything can be taken at face value. The untutored visitor won’t necessarily know that what we see embodied in here is a Western romanticisation of the Middle East. (Ironically, the painting used on the cover of early editions of Edward Said’s Orientalism, Jean-Léon Gérôme’s The Snake Charmer, 1880, appears in this show.)

The approach to interpretation at immersive art venues does vary. Frameless in Marble Arch, London, is the ‘largest permanent multi-sensory experience in the UK of its kind’, offering a tour through some of the greatest hits of Western art history, organised into loosely thematic displays. The entrance to each is accompanied by a list of works and text panels that provide some useful context. In ‘Colour in Motion’, visitors will find projections of masterpieces by Van Gogh alongside those by Monet, Seurat, Paul Signac, Robert Delaunay and Berthe Morisot. The selection makes sense: their brushstrokes – already separate and definable – can easily be separated further. In the case of Seurat, the pioneer of Pointillism, each dot of paint was pixel-like already. Such brushwork lends itself to animated motion of various kinds. Here, Monet’s water lilies are broken down into individual strokes that lie in drifts on the floor. As you walk through, these respond by scattering in your path before floating up the walls and resolving themselves into a recognisable image.

Interior view of Atelier des Lumières, Paris. © Culturespaces/C. de la Motte Rouge

It’s at Frameless that I notice one important upside to this gargantuan mode of display. The central panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490–1510) by Hieronymus Bosch is only 185.8.cm high. Anyone who has visited the triptych in the Prado in Madrid will attest to the difficulty of taking in this complex work in person. With highly detailed work such as this, a huge increase in scale is helpful. The least successful display at Frameless is that with least incident in its source material. In ‘The Art of Abstraction’, paintings by the likes of Mondrian and Malevich are projected on to zig-zagging screens, taking on the appearance of so many room dividers.

Instead of relying solely on centuries-old paintings, immersive arts businesses are increasingly interested in commissioning contemporary artists. A new venue, Lightroom in London’s King’s Cross, opened in February 2023 with ‘David Hockney: Bigger & Closer (not smaller & further away)’. This 50-minute, 360-degree film shows Hockney drawing alongside a selection of his work, from 1960s paintings to iPad experiments of the 2010s. These are accompanied by narration from the artist and a soundtrack by composer Nico Muhly.

‘Immersive shows were all doing something to an artist, not with an artist,’ Lightroom’s CEO Richard Slaney tells me. He does not see what the company does as comparable with what is offered by Frameless and the like, though he describes the latter as ‘great fun’. Instead, he says, ‘Lightroom is all about the engagement of the artist in the process, and the soundtrack becoming a meaningful part of the art.’ The resulting spectacle was loved by audiences – it returns from 9 June – yet less popular with critics. The Guardian’s review was headlined ‘An overwhelming blast of passionless kitsch’.

Outernet, an immersive space in the West End of London, made the news in January when it reported visitor figures higher than the British Museum’s: 6.25 million in 2023, its first year of operation, versus 5.83 million. (It’s worth noting that Outernet is free, open on three sides and located by the entrance to Tottenham Court Road tube station. It’s unclear how many people were taking a shortcut.) Passers-by will find wraparound LED screens hosting everything from a child-friendly shower of emojis (no artist named) to Silent Writings, a digital artwork by Barbara Kruger currently on show in partnership with the Serpentine.

Alongside artists such as Kruger and Hockney working primarily in analogue mediums, a new generation of digital artists are also creating immersive works. This includes Refik Anadol, whose solo exhibition ‘Echoes of the Earth: Living Archive’ is currently at the Serpentine North Gallery. Anadol uses AI to create moving image works designed for immersive settings or enormous screens. For the Serpentine, the artist’s AI used tens of thousands of images of nature photography to generate flowers, fungi and birds that belong to no particular species.

Installation view of ‘Echoes of the Earth: Living Archive’ (2024) by Refik Anadol at the Serpentine Gallery, London. Photo: Hugo Glendinning; courtesy Rejik Anadol Studio and Serpentine Gallery; © the artist

For all the differences between Anadol’s work and Hockney’s experiment with immersive art, both have been criticised for prioritising spectacle over substance. Anadol and New York Magazine’s senior art critic Jerry Saltz had an online spat over Unsupervised (2023), a seven-metre-square abstract work then on show at MoMA, which Saltz called a ‘massive techno lava lamp’ and ‘a half-million-dollar screensaver’. Kay Watson, head of arts technologies at the Serpentine, tells me: ‘It’s taking a very long time for technologically based practices to be accepted by the mainstream art world.’ Watson is keen to stress that the growing field of projection or screen-based immersive art is only the beginning.

Arguably, it was ever thus. Immersive art can be traced back at least as far as a form of painting invented in 1787 by the Irish artist Robert Barker, who coined the term ‘panorama’. Barker patented a system whereby huge works painted on the interior of a cylindrical ground could be viewed from an inner platform. Much like today’s spectacles, his panoramas existed in a hinterland between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ taste. Our desire to be immersed in an experience has never gone away.

Atelier des Lumières, Outernet and Lightroom are among the hundreds of such businesses to have opened in the past five years. Entrance fees for adults usually range between £15 and £30: equal to or greater than the ticket price for an exhibition of physical objects, yet without the costs associated with more conventional exhibitions (art shipping, insurance, loans, conservation, etc.). In January, Arts Council England announced a three-year, UK-wide ‘Immersive Arts’ programme. The £6 million budget is intended to support 200 artists and organisations to develop virtual, augmented and mixed-reality technologies. In an accompanying statement, Saqib Bhatti, minister for tech and the digital economy, said: ‘Extended reality brings about artistic innovation and a list of economic benefits that goes on and on and on.’ Like it or not, immersive art – in many and varied forms – is here to stay.

From the April 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

The art world mutates faster than the human eye can take in. It resembles the fashion industry far more than it does, say, publishing or theatre or even Hollywood, which all seem gentle by comparison. It is not, then, such a great shock that the stately Marlborough Gallery, founded in 1946 in the age of high-minded modernism, has decided to call it quits after 78 years.

Marlborough comes from an age of Modern Masters, its undisputed greatness appearing to lift it above market fluctuations or changing tastes. Francis Bacon and Mark Rothko, surely the greatest artists since the second world war in figurative and abstract painting respectively, were both represented by this dealer, which exerted huge influence on both sides of the Atlantic.

It is no coincidence that despite having maintained its aura of “blue chip” eminence through the postmodernist 1980s and beyond, Marlborough is closing at a time when the very concept of artistic greatness it relied on is being questioned, the canon gleefully upturned. Not that Marlborough only dealt in dead white males. It also represented the visceral painter Paula Rego through her unfashionable years, when she was seen by some as a dreary figurative artist rather than the kick-ass icon she is now. She left in 2020 to join the much more cutting-edge Victoria Miro Gallery, which promotes her as an explicitly feminist artist alongside Chris Ofili and Grayson Perry.

Presumably one day Victoria Miro too will look old while White Cube will seem positively antediluvian. Cool gallerists in the past, such as Robert Fraser, John Kasmin or Anthony d’Offay all failed to keep up with new generations and faded away.

So perhaps the real story here is how Marlborough managed to last nearly eight decades when so many galleries have only a decade in the sun. This confirms its business model of selling apparently timeless artists was pretty effective. Even if the great Frank Auerbach has never been exactly groovy, representing him, as Marlborough did until recently, must be counted an asset.

Or is it? Will Auerbach be remembered when he’s gone? There are no longer any certainties about art surviving as the idea of greatness is relativised, not by radical academics, but the mainstream art market. Marlborough is passing into the past along with the 20th century “masters” it dealt in so prestigiously. It was a relic of a vanished world. Capitalism is merciless, art capitalism triply so.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

When the musician Laurie Anderson was beginning her career in the early 1970s, an avant-garde artist who wanted to work at scale had to go abroad — to one place in particular.

“I got my start in Germany, because of state-supported art,” recalled Anderson, who exhibited at its national museums and performed with its symphony orchestras when she was still an emerging talent. She lived for a time in West Berlin. She met Lou Reed, her future husband and a sometime Berliner himself, in Germany in 1992.

Fitting, then, that she would accept a prestigious guest professorship this year at a German art school. Then, in late January, a local blogger fulminated after finding her signature among 16,000 names on a two-year-old open letter that denounced “apartheid” in Israel and the Palestinian territories. The university then called, seeking explanations. Rather than distill her thoughts about “this unbelievably tragic war” into the kind of public statement they seemed to want, she withdrew. “It did teach me that I didn’t really want to have that kind of sponsorship,” she concluded. “If I’d known they were going to ask things like that, I never would have accepted that job in the first place.”

She’s far from the only artist who finds herself unsure of her welcome here these days. The arts scene in Germany — and especially Berlin — has been turned upside down by Hamas’s attacks in Israel on Oct. 7, and the siege and bombardment of Gaza.

Prizes have been rescinded. Conferences called off. Plays taken off the boards. Government cultural officials have suggested tying funding to what artists and institutions say about the conflict, and media — both traditional and social — bubble with public denunciations of this writer, that artist, this D.J., that dancer. The disinvitations have brought counter-boycotts. And a climate of fear and recrimination has put Berlin’s status as an international cultural capital in greater hazard than at any time since 1989.

Berlin had once been the artistic beacon of all Europe, but what’s happening here today is a very German story. The country’s responsibility for the Holocaust still defines a cultural sector whose institutions are committed to a national process of reckoning and atonement. That culture of remembrance also undergirds Germany’s staunch support for Israel, and the strict limits it places on criticisms of its ally. (Only recently has the rising toll in Gaza prompted some German leaders to question their unwavering support.) So while artists around the world — from the stage of the Oscars to the Whitney Biennial — have been vocal about the war, in Germany such statements can have a major cost: canceled performances, lost funding, and accusations of antisemitism in a society where no charge is more serious.

“Berlin was broke, but a community was there,” said the electroclash star Peaches, who has lived here since 2000, when we met up for breakfast in Prenzlauer Berg. I asked her what’s changed lately, and she noted how risk-taking institutions were already running scared amid threats to funding. “What was going on here was openness to all these intersections. And since the last few months, there’s been a lot of that taken away.”

That sense of new limitations, new controls, new anxieties, is already exacting a price on culture in a city that had made a welcome of artists into its post-Wall calling card.

“This angst makes it harder for us to work internationally, attract the best talent on the highest level and bring diverse audiences together,” said Klaus Biesenbach, the director of the Neue Nationalgalerie, who previously led museums in New York and Los Angeles. “If the artists leave, one of the last real bonuses that Berlin has would be gone.”

The cancellations, postponements and uproars have hit every cultural sector, with anger and accusations coming from as high as the chancellery. The Berlin International Film Festival saw withdrawals and protests this year — and after its closing ceremony, at which several laureates called for a cease-fire in Gaza, federal and state officials issued threats to withhold future support.

D.J.s have been dropped from lineups at Berghain and other clubs, sometimes after posting anti-Israeli statements, but often for much milder support for Palestinian lives.

The Maxim Gorki Theater, one of the city’s most acclaimed playhouses, canceled a prizewinning play about Israelis and Palestinians in Berlin — leading several intellectuals and artists to cancel appearances there in turn.

In the galleries of the KW Institute for Contemporary Art, a hub for the city’s art scene, recently shipped sculptures are sitting in unpacked crates. Their creators now refuse to exhibit in Germany to protest what they describe as restrictions of speech supporting Palestinians.

Some cultural leaders are raising alarms. In January, the Berlin state government proposed a new funding clause that would require grantees to sign a document opposing “any form of antisemitism” — and used a definition that listed certain criticisms of Israeli policy as antisemitic. Artists protested, and the proposal was withdrawn, but the outgoing director of the Goethe-Institut, which promotes German language and literature abroad, fretted in Der Spiegel that “longstanding partners in the international cultural world are losing confidence in the liberalism of German democracy.”

For many artists, especially foreigners who settled in Berlin as a place of freedom and cultural abundance, the very survival of the city as an artistic capital is in doubt, or perhaps already gone.

“Berlin, in my view, is not a place where artists can create freely,” said Ai Weiwei, the Chinese artist and dissident, who keeps a studio in Berlin but no longer lives here. “Whenever I hear about German government officials imposing restrictions on artists’ freedom of speech, or expression, it fills me with despair.”

It’s of course not just in the capital. The Frankfurt Book Fair “indefinitely postponed” a prize ceremony for Adania Shibli, an acclaimed Palestinian writer and Berlin resident. The city of Bremen reneged on its own prize ceremony for the Jewish writer Masha Gessen over an essay comparing Gaza to the ghettos of Nazi-occupied cities. The Berlin-based artists Jumana Manna, who is Palestinian, and Candice Breitz, who is Jewish, both had exhibitions at regional museums canceled on the grounds of (as usual) controversial social media posts. Even Greta Thunberg, the climate Cassandra, has been canceled in Germany after wearing a kaffiyeh and calling for a cease-fire at a recent protest.

But it is Berlin that stands to lose the most from all these disinvitations and denunciations, and from the larger malaise in German democracy from which they spring. The success of the far-right Alternative for Germany party, and the broader advance of the populist right in Europe, have shaken postwar and post-Wall norms of historical responsibility. The arrival of a million refugees from Syria and elsewhere in 2015 continues to shape ongoing debates about who is a German. New spending freezes and austerity budgets, triggered by restrictions on government debt, spell trouble for a capital that still has three major opera houses.

All this while indisputably antisemitic rhetoric, and even violence, have been rising in Germany. In October, masked assailants chucked Molotov cocktails at a synagogue (they missed; no one was hurt). Anti-Jewish slurs and stars of David were painted on government buildings and residences.

When pro-Palestinian activists came to the Hamburger Bahnhof, one of Berlin’s leading institutions for contemporary art, and shouted down the director of one of the country’s Jewish museums with slogans such as “Zionism is a crime,” they affirmed the belief of many here that anti-Israeli rhetoric is just a step away from antisemitism.

Against that backdrop, some Jewish Berliners see criticism of Israel as much more than a foreign policy dispute. “I’m an aggressive Zionist for only one reason: because I want to survive,” Maxim Biller, the author of the novel “Mama Odessa” and one of the country’s leading columnists, told me over coffee. “And I can be a German writer with a Jewish project here only because there is a state of Israel.”

Naturally there is a German compound noun for that interdependence, endlessly slung around and debated in the last few months. The word is Staatsräson, or “reason of state”: a national interest that is not just nonnegotiable but existential, defining the state as such. Angela Merkel, the former chancellor, described Israel’s security as Germany’s Staatsräson in a historic address to the Knesset in 2008. Her successor, Olaf Scholz, has repeatedly invoked Staatsräson in his defenses of Israeli policy since Oct. 7.

“Staatsräson means: The existence of Israel is a condition of possibility for the existence of Germany,” explained Johannes von Moltke, a professor of German cultural history at the University of Michigan, who’s currently in Berlin. “Because if there is no Israel, then Germany’s guilt is all-consuming again. And you can’t countenance that possibility.”

In other words, the cultural crackup of the last few months only appears to be part of an international conflict. It is, in fact, resolutely German. What is really being fought over here is a hazy, transcendent national concept that, since Oct. 7, has overtaken more firmly constitutional principles of free expression and free association.

The tensions have been building since at least 2019, when the federal Parliament adopted a resolution designating the movement calling for a boycott of Israel as antisemitic, and urging local governments and “public stakeholders” not to fund organizations or individuals that support it. That makes a big difference here, since so many artists, writers and musicians receive generous government aid. The resolution, though nonbinding, led some cultural institutions to rescind invitations to critics of Israeli policy, and many more to take a hesitant approach.

“People in cultural institutions are risk-averse,” said Tobias Haberkorn, who edits the Berlin Review, a new literary publication. “So if they have to decide, ‘Am I going to invite this or that artist with a Middle Eastern background, or not?’ I can very well see them not inviting them. Just to avoid the potential hassle.”

Since Oct. 7, accusations of antisemitism have flown much more broadly. Some are merited. Many others are dubious. Quite a number of those accused of antisemitism have been Jewish, such as Gessen.

“There are many Jewish perspectives, and that is not being honored here in a country where the history cannot be excused,” said Peaches, who is also Jewish. “For any progressive Jewish person who is thinking about what is going on, and understanding the history of what is going on, to be called antisemitic — by Germans — is ridiculous. Never did I think in 2024 that I would be thinking about that.”

Yet it’s worth pointing out how few of these accusations revolve around cultural production. It is rare for Berlin’s theaters or festivals to cancel someone for what they actually sing or paint or film. What gets you now are statements, posts, likes, signatures: the imperatives of social media, which are swallowing culture wholesale. Once debates like this would have played out in Germany’s elite press, where intellectuals clashed over the country’s moral responsibility to the past. Today the national papers, and the institutions too, are playing catch-up to Ruhrbarone, a small website from the provincial city of Bochum that took down Anderson and many others.

Perhaps the lowest point yet came at the end of this year’s film festival, when numerous prizewinners called for a cease-fire in Gaza; two went further, using the words “genocide” and “apartheid” to describe Israel’s actions. That prompted Germany’s culture minister, Claudia Roth, to announce an inquiry into the film festival’s governance. In a subsequent interview with Der Spiegel, Roth said that “the freedom of the arts includes curatorial responsibility,” and suggested that the festival’s organizers had to ask themselves: “Which films are being selected? How are the juries appointed?”

The festival’s outgoing artistic director, Carlo Chatrian, hit back at that government interference in an open letter, accusing German officials and news organizations of rhetoric that “weaponizes and instrumentalizes antisemitism for political means.”

Surely this city ought to have learned by now that directing culture toward political ends rarely ends well. Those who have forgotten might take a walk over to the Gendarmenmarkt, a grand central square now gashed by construction barriers, and its monumental statue of a German playwright and philosopher with a rather subtler understanding of how culture and government inform each other. His name was Friedrich Schiller, and what he saw was that the arts were not aristocratic luxuries, not decorations; they were the very motor of human freedom. The arts, Schiller taught his fellow Germans in 1795, “enjoy an absolute immunity from human capriciousness. The political legislator can bar the way to its domain, but he cannot rule within it.”

This freedom of the arts still defines Berlin, which knows better than most cities what dangers lurk when they are overregulated. It defined the Weimar period, when Otto Dix caricatured the powerful and August Sander photographed society without embellishment. And the postwar era, when novelists forged a new German literature in a register that definitively broke from the Nazi past. And also the Cold War, when punk bands on either side of the Wall made music in defiance of national aims. And especially the heady years after reunification, when a global generation of designers and D.J.s reestablished the unlovely city as Europe’s beating heart.

Lose that cultural freedom and you lose much more than a “scene.” You lose the very ground — the ground of sympathetic imagination — upon which you combat antisemitism and all other forms of bigotry. “The opportunity to experiment for creatives and artists from all over the world is one of the most important things Berlin still has going for it.” said Biesenbach. “We need to protect it.”

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

The sleek suspense of a mob thriller and the big, dramatic swings of a telenovela combine to produce something truly unpredictable in “Rest in Peace,” by the Argentine director Sebastián Borensztein. We first meet Sergio (Joaquín Furriel), a handsome business owner and beloved husband and father, as he’s tearing up at his daughter’s lavish bat mitzvah; in moments, the mood shifts, when he spots a menacing stranger eyeing him from a corner and faints. As his wife, Estela (Griselda Siciliani), soon discovers, Sergio is drowning in debt and facing threats from a mysterious, ruthless lender. Their picture-perfect existence is on the verge of shattering — and then it does, albeit not how either of them (or the viewer) might have expected.

A tragic accident offers Sergio a way out of his predicament, though at the cost of his life with his family. The twists of the film are best left unspoiled, because Borensztein and his fine cast (Siciliani is majestic, in particular) achieve an impressive series of tonal tilts in the course of a narrative that eventually spans decades. Just when you think a cat-and-mouse game is about to begin, the film douses you in endearing romantic and familial drama; just as surprisingly, danger creeps back into the narrative. The result is a movie whose genre pleasures are undergirded by genuine emotional heft.

Between 2013 and 2015, in the midst of the Syrian Civil War, the Yarmouk Palestinian refugee camp in Damascus — known colloquially as “Little Palestine” — was placed under siege. Citizens were barred from entering or exiting the area, and eventually, food and water were restricted, leading to widespread starvation. Amid all this horror, Abdallah Al-Khatib, a Yarmouk resident in his 20s, picked up a video camera and started recording what he saw around him: the tremendous suffering, but also the resilience of resistance.

Edited over several years, “Little Palestine, Diary of a Siege,” which premiered at festivals in 2021 and now arrives on streaming, is a dispatch from the past with uncanny echoes of the present. Al-Khatib’s camera captures his community as they sing, paint, chant, rally, scrounge for food and try to take care of one another. His interactions with the older generation — Palestinians who have endured many displacements over decades — are poignant, underscoring the oppressive cycles of history. But it’s his conversations with the children of Yarmouk, aged far beyond their years but still not rid of hope, that have stayed with me. In one shot, a crowd of schoolboys share their dreams with the camera. Their beaming, excited smiles belie the tragedy of their words. “I dream of my brother coming back to life,” says one. “I dream of eating sugar,” says another.

This portrait of Funky Town, an underground nightclub in Chengdu, China is a hypnotic, mutating beast; it goes seamlessly from night to day, techno to the noise of traffic, nonfiction to gently staged drama. To capture the cultural place of this beloved institution — a bastion for free expression and desire that is soon to be shut down because of a subway expansion — the director, Ben Mullinkosson, follows a few of its regulars in and out of the club: a young drag queen, a woman struggling with mental health issues, a Russian expatriate exploring his sexuality, an exuberantly gay DJ. Instead of traditional interviews and documentary scenes, the movie finds intimate moments within layered, often ironic, compositions. In one shot, two people have a deep conversation in the background while a woman vomits into a cup in the foreground; in another, a high-angle shot of a crowd on a street makes the scene look like a kind of pointillist painting. Formally and emotionally expansive, “The Last Year of Darkness” is a stirring evocation of the beauty and ephemerality of being young.

Two strangers cross paths on Christmas Eve in Mumbai. He’s just returned from a trip; she’s out in the city with her young daughter, having been abandoned by her philandering husband. A chance meeting at a restaurant leads to another encounter at a movie theater, and then a walk through the city and a drink and a dance back home. Sriram Raghavan’s movie takes its time with its setup, indulging in each scene and exchange with patience and exquisite detail, never showing all of its cards.

From the very first minute to the very last, “Merry Christmas” keeps you guessing — about the motives of the characters, their fates and the type of movie this is. Rom-com? Crime thriller? Black comedy? It’s a little bit of everything, and it’s executed with impeccable yet restrained style, much like Raghavan’s prior outing, “Andhadhun.” The stars, Katrina Kaif and Vijay Sethupathi, are at once mysterious and winningly sincere, and the film’s storybook-like rendering of a Mumbai decked out for Christmas is delightful.

There’s a moment in Kamila Andini’s sensitive coming-of-age drama that will feel familiar to many women, whether or not they grew up in the rural Indonesian town where the film is set. In a grassy field, a group of high-school girls whisper about sex and desire. It’s the question of pleasuring oneself that both excites and scares them the most. Can women even do it? How does it work? They ask each other.

“Yuni” is about women’s oppression — about the social forces that constrain girls from pursuing their dreams — but its strength lies in its focus on women’s pleasure. The movie’s protagonist, the high-school senior Yuni (Arawinda Kirana), faces some tough dilemmas. She wants to go to college, but her family is already entertaining potential marriage for her. She is eager to explore her body on her own terms, but her school has instituted mandatory virginity tests for the girls in a twisted response to a case of rape.

Things are bleak, and Andini’s sobering film offers no miracle escapes, but it makes it a point to show us the defiance of Yuni and her classmates, their small yet powerful negotiations in this constricted world. Shot with tactile sensuality, as if in formal protest of the systems the movie critiques, the best scenes in “Yuni” are its moments of intimacy between women — dancing, gossiping or dreaming together, helping each other survive an unforgiving world.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

The National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., has hired Natalia Ángeles Vieyra to serve as its first associate curator of Latinx art. She will begin in her role on July 1.

Currently an independent curator, Vieyra is a specialist in Latinx, Latin American, and Caribbean art from the 19th century to today. Her dissertation at Temple University focused on Puerto Rican artist Francisco Oller.

She most recently worked as an associate curator of American art at the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts, where she helped the institution secure several acquisitions of Latinx and Latin American artists. She has also held a fellowship at the Harvard Art Museums and curatorial roles at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia and the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam.

In a statement, Vieyra said, “I am incredibly honored to join the National Gallery of Art at this pivotal moment in its history. I am excited to connect with and inspire Latinx communities through art, and to champion Latinx artists on the national stage.”

At the NGA, Vieyra will join the museum’s modern and contemporary art department, where her focus will be on studying and growing the NGA’s holdings of work by Latinx artists, which currently includes works by as Ana Mendieta, Felix González-Torres, Rupert García, Carmen Herrera, Daniel Lind-Ramos, Freddy Rodríguez, Christina Fernandez, Miguel Luciano, and Martine Gutierrez.

In a statement, E. Carmen Ramos, the NGA’s chief curatorial and conservation officer, said, “We are thrilled to welcome Natalia Ángeles Vieyra as our first curator of Latinx art. The span of Natalia’s scholarship and curatorial practice from late 19th- to early 20th-century Puerto Rican art to contemporary art, is well suited to the National Gallery’s transhistorical collections. As a scholar of Latinx art myself, I look forward to supporting Natalia as she helps deepen our collections and develops projects that illuminate the important ideas and practices of Latinx artists, highlighting their relevance to our world, past and present.”

This new curatorial position at the NGA comes as part of the Advancing Latinx Art in Museums (ALAM) initiative that was announced in February 2023. A partnership between four of the country’s leading philanthropic organizations, the Mellon, Ford, Getty, and Terra foundations, ALAM pooled together $5 million to give 10 US museums $500,000 each to hire curators focused on Latinx art; the NGA’s grant comes via the Getty’s funding.

Of the 10 ALAM-funded roles, five represent newly created positions at institutions, reserved for early-career curators. In April 2023, the Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas at Austin hired Claudia Zapata as its first associate curator of Latino Art as part of the grant it received through ALAM.

But museums hiring specialists in Latinx art is also part of an increasing trend in the field. Last October, the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio hired Mia Lopez as its first curator of Latinx art.

Ramos added in her a statement, “This is an exciting moment for the National Gallery of Art as we inaugurate a new position that will bring visibility and increase scholarship of Latinx art and help us better serve our national community.”

Photo David Heald/©Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York. Copyright: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York. All rights reserved.

Additionally, the National Gallery of Art also announced that it had hired Lena Stringari as chief of conservation, beginning July 14.

Stringari, who is currently deputy director and chief conservator at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, will oversee six conservation departments and a scientific research department that work to preserve the NGA’s collection of some 160,000 objects.

During her more than 30-year tenure at the Guggenheim, Stringari helped establish the museum’s acclaimed Variable Media Initiative in 1999, which helped set a standard for the preservation of media-based works and performance pieces. She also led the 10-year Panza Collection Initiative, which involved conservation and research into works of Minimalism and Conceptualism from the 1960s and ’70s. More recently, she organized conservation-focused exhibitions on works by Jackson Pollock and Eva Hesse.

In a statement, Ramos said, “Lena’s impressive experience in leading complex teams and undertaking major conservation projects and research, as well as her commitment to sustainability and nurturing future generations of conservators, all make her an ideal leader for this role. I eagerly look forward to working with her in support of our talented conservation team and its service to our audiences and the nation.”

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

My kids squeal with delight when they discover refractions cast on our walls by light through our sun catcher. Even I still marvel at the phenomenon and serendipity, pausing to take notice whenever the occurrence catches my eye. For Draga & Aurel – an Italy-based multidisciplinary studio founded by Draga Obradovic and Aurel K. Basedow – the wonder of such natural occurrence is so marvelous that it served as inspiration in their latest collection, Flare. Consisting of seven different coffee tables and a totem sculpture, the series is an actualization of fractal concepts.

Working with the artisans on Lake Como where Draga & Aurel are located, the designers combine sheets of lucite that have been produced in different colors and thicknesses to create interesting gradients and hues. The sheets are then cut again and glued, producing that familiar effect of light refracting through an object in a kaleidoscope of color. The resulting tables and totem evoke feelings of revelation, discovery, and awe at every angle.

FLARE is a spark of color that explodes, frees itself, and takes shape. It’s joy, experimentation, intuition, and freedom of expression.

– Draga & Aurel

The Flare collection is available exclusively at the New York gallery, Todd Merrill Studio. To learn more about the designers, visit draga-aurel.com.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

For landscape artist Marcia Burtt, acrylic paint has been a perfect medium for her creative process and techniques. “The biggest benefit,” she says, “is that the medium allows me to paint without having to worry about what the finished piece will look like. I can experience each session as a joyful adventure with no apologies, agony, or recriminations. I don’t have to plan or draw beforehand because I know I can obliterate or repaint later without regret.” Last year, when Burtt served as the Juror of Awards for the 10th annual AcrylicWorks art competition, she enjoyed seeing the exciting variety in the entry pool—and the wealth of talent. The following honorable-mention-winning artworks she selected are a great example of the tremendous diversity and boundless creativity to be found in contemporary acrylic painting. Start browsing 10 acrylic works to kickstart your own creative engine!

If you paint with acrylics, don’t miss your chance to participate in the latest AcrylicWorks competition. In addition to cash awards for three top winners, 100+ finalists will be featured in the annual publication, The Best of Acrylics. Enter today! Final deadline is April 9, 2024.

I Only Want to Be With You by Hanna MacNaughtan

I Only Want To Be With You was inspired by the most beautiful little meadow that grows along the river not far from my home. On certain days when the light is just right, there’s a beautiful golden glow that rises up all around it. Perhaps it’s caused by the light reflections from the river that runs along the far edge.

In Retrospect by Cher Pruys

I absolutely love working in acrylics. The fast-drying characteristic of this medium is, at times, a bit challenging when it comes to blending, so I find it crucial to water down my acrylic paints. The 300-lb. hot-pressed surface aids in the successful portrayal of fine detail that’s such an integral part of my work.

Nest Foraging by Reenie Kennedy

Birds often inspire my work, as they add a punch to most settings. Just looking at them sets my mind on a storytelling path. Because it dries fast, acrylic is an excellent medium for layering colors, as I did here, to add depth and shadows to the work. My goal for this piece was to form a balance between warm and cool tones among the intricate weave of reeds, guiding the eye from shade to bright sunlight and around the composition.

Flow—Hold the Key to Open the Door of Memory by Haoran Chang

When a ray of light shines, the opposition between reality and emptiness will affect us. When the key between your fingers opens the door of memory, you must decide whether to move forward toward the light or retreat into the endless darkness.

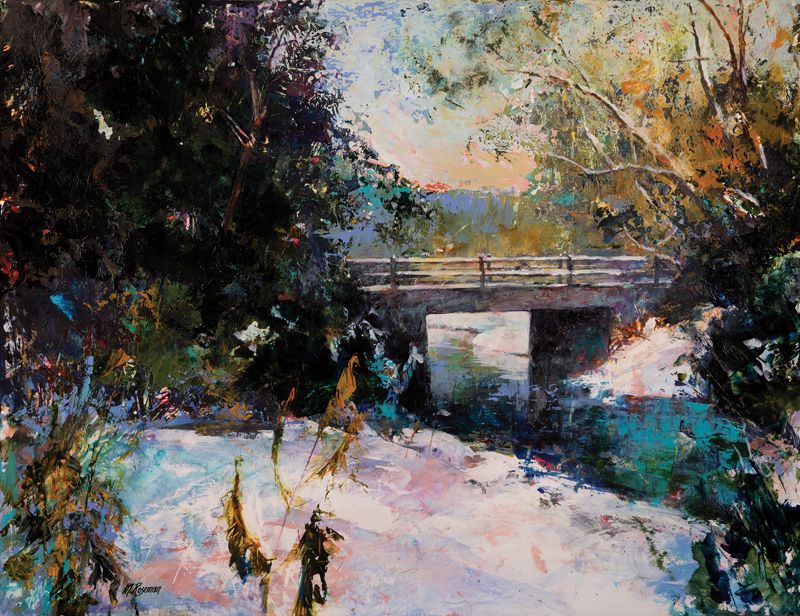

Winter Sunset by Margaret Roseman

Working with acrylic paints on Yupo paper allows me to create works that push toward abstraction while still capturing the atmosphere inherent in a landscape. Applying layers of unexpected color in both a transparent and opaque form produces a unique textural quality that captures the sparkle of light. In all of my works, the tendency for near-abstraction and dramatic contrast allows me to manipulate form and color to capture the essence of a scene.

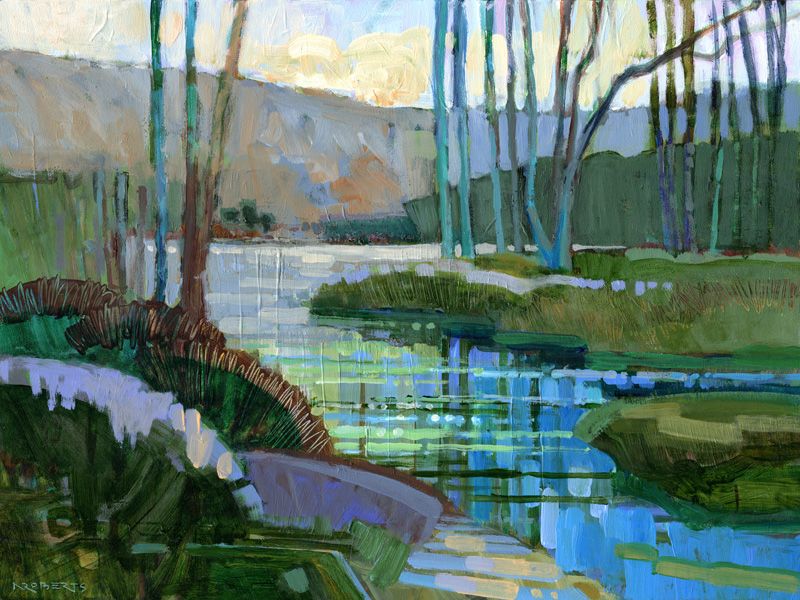

Creek Song by Nancy Roberts

I started Creek Song along a quiet creek near my home in Northern California, then continued it in my studio, working from memory and imagination. Using both heavy body and Golden OPEN acrylics on an Ampersand Gessobord panel, it was a joy to explore and sculpt the design—building with sheer layers of color, impasto passages, linear marks, and scraped patterns as this shimmering new landscape emerged. My paintings tell me what they want. My job is to listen.

After the Rain by Shu-Chih Murray

Painted from life in my studio, these yellow irises came from my garden. I started the work by laying the irises on my canvas to arrange the composition. I applied water to the canvas before using acrylic ink, creating natural waves and curves. Then I switched painting techniques and used acrylic ink before adding water, allowing gravity to do its job. Once dry, I used water-soluble oil for details.

Sunlit Green Apples by Tai Meng Lim

I captured the various colors of the apples in reference photos before I started painting. I chose natural sunlight as the illuminating source and experimented with different exposures and settings. Once I had the reference, I prepped the ground with gesso and then carefully mapped out the drawing on illustration board. Next, I created the underpainting with a raw umber color to define the value. I followed that with more applications of color in multiple layers, working from thick to thin to build up a realistic image. To build the transparency and reflective effects, similar colors were then painted next to one another in a sequence of shapes and lines, creating a flow that provides the composition with a sense of dynamism.

Twilight by Linda Heath Clark

Twilight was created using subtractive scratchboard techniques with acrylic on a white clayboard surface. I achieved the final three-dimensional effect by alternating painted layers of high-flow acrylics with the selective removal of the dried acrylic by scratching through to the white clay below using knives, scalpels, tattoo needles, fiberglass brushes, and steel wool. I then reapplied thin washes of acrylic and scratched again. Scratching creates highlights and details. Washes of acrylic tint the scratches, suggesting contours and shadows. The scratches are fully visible when viewed up close, yet from a distance, the piece blends into a harmonious whole.

Out to Pasture by Carol Loeb

Rusty objects, from old factories to abandoned vehicles to ancient metal containers, are favorite subjects of mine. I’m intrigued and captivated by the variations of colors and textures on the metal as time and neglect claim another victim. In Out to Pasture, I limited my color palette to warm orange-browns and soft blue-grays, eliminating everything else around the tractor to keep the focus on it. I applied layers of opaque acrylic paint for the lichen, and used translucent acrylic paint to build up depth within the metal surfaces. The subject is the tractor, but the story is about time.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

Claude Monet's sun-dappled riverscape Moulin de Limetz (1888) will be sold in May during Christie’s 20th century evening sale in New York, where it is expected to fetch between $18m and $25m. Moulin de Limetz is partially owned by the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, while the descendents of the woman who donated the painting retain a share.

Moulin de Limetz features a view of a grain mill on the River Epte in France, roughly a mile away from the artist’s longtime home in Giverny. The painting was first acquired from Monet by famed Impressionist art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel.

Joseph S. and Ethel B. Atha, celebrated collectors in Kansas City, acquired Moulin de Limetz sometime after 1936. The Atha family traces its roots in Kansas City to the early 1900s, when Frank Perry Atha expanded operations of the Folger Coffee Company to the American Midwest from California. When Ethel died in 1986, Moulin de Limetz was partially bequeathed to the Nelson-Atkins in a unique deal that allowed the museum and family to share the painting. The work has hung at the museum since 2008. After the death of Ethel’s daughter, Evelyn Atha Chase, in September 2023, her family decided to sell its one-third share in the painting, and worked with the museum to move forward with an auction. Proceeds from the museum’s share of the painting will go toward creating an endowment in Joseshp S. and Ethel B. Atha’s names.

"We are so grateful to the Atha family for their generosity, which has made it possible for us to share this wonderful Monet with our community for many years,” Julián Zugazagoitia, the director and chief executive of the Nelson-Atkins, said in a statement. “While we did pursue the possibility of acquiring the family’s remaining share, this was ultimately not possible. However, while we will miss this beautiful work, this sale is also an opportunity for the museum to create the Joseph S. and Ethel B. Atha Art Acquisition Endowment with the auction proceeds that will allow us to acquire art to honour the family in perpetuity and continue adding to and refining our exceptional collection.”

There are two versions of Moulin de Limetz completed by Monet in 1888. The other painting was sold at Sotheby’s New York in November 2023 for $25.6m, with fees. That version was acquired by the Hasso Plattner Foundation and early this year, the painting joined the collection of Museum Barberini in Potsdam, Germany, on permanent loan.

The Nelson-Atkins has four other paintings by Monet in its collection. This month marks the 150th anniversary of the first Impressionist exhibition in Paris.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

Paris’s Louvre Museum has returned Hans Holbein’s portrait of Anne of Cleves to the Richelieu Wing after the 1539 painting was removed for conservation and cleaning. The portrait has been in the collection of the Louvre since the museum’s 1793 opening.

The differences achieved by the restoration team are impressive, particularly in the removal of built-up layers of dirt which revealed the original bright blue background behind Anne of Cleves, which for many years has appeared to be a murky sea green.

Hans Holbein, Anne of Cleves (ca. 1539). Photo: © 2017 RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Tony Querrec.

A before-and-after comparison was analyzed by the British historian, broadcaster, and author Owen Emmerson in a video posted on his X account on March 13. Emmerson called the results “absolutely breathtaking,” highlighting that we can now fully appreciate Anne’s rich red gown and its shining pearl detailing. In another post, Emmerson pointed out that when his late 18th-century copy of the painting was cleaned, “a sludgy green background was revealed, suggesting [that the true bright blue background] may have been concealed for centuries.”

The cleaning process has also brought dazzle back into the jewels worn by the future Queen of England, including a bejeweled gold cross necklace and several gold rings. These jewels have been documented in close-up photos in the museum’s March 12 Instagram post announcing the return of the painting to room 811. Room 811 contains works by Dutch artists made in the first half of the 16th century.

Detail of Hans Holbein, Anne of Cleves (ca. 1539). Photo: © 2017 RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Tony Querrec.

It was this portrait by Hans Holbein the Younger that famously sealed the deal on the marriage between the then 24-year-old Anne and 48-year-old King Henry VIII. Anne, born Anne von der Mark, was the second eldest daughter of Duke Johann III of Cleves—a Catholic state on the Rhine—and had been promised in marriage to the son of the Duke of Lorraine since she was 12. After the death of Henry VIII’s third wife, Jane Seymour, in 1537, the king sought out new brides in European courts. The King commissioned court painter Holbein the Younger to create portraits of Anne and her younger sister Amalia, who had been suggested by the King’s chief minister Thomas Cromwell.

When Anne arrived in England, Henry was displeased with the reality of his new bride’s looks in comparison to the vision promised in Holbein’s portrait. Cromwell had assured the king of Anne’s beauty, saying that “every man praiseth the beauty of the same lady as well for the face as for the whole body,” but Henry was deeply disappointed. Despite apparently exclaiming, “I like her not! I like her not!” at their first meeting, the pair married on January 6, 1540. Six months and six days later, the pair’s marriage was annulled on grounds of non-consummation.

Anne of Cleve’s marriage was the shortest-lived of Henry’s six marriages. She lived out the rest of her life in an a respected position in court, known as the “King’s Beloved Sister” and outlived each of Henry’s next two wives. She was even invited to Hampton Court Palace for Christmas in 1541 in attendance of Henry’s new wife Catherine Howard, whom he had married 16 days after his marriage with Anne was annulled.

An updated photo of the painting has been added to the artwork’s listing on the Louvre collection website, but no further information on the restoration has been released by the museum.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

Since mid-February, Holly G’s email inbox has been filling up with at least half a dozen press requests a day.

At the time, Beyoncé had just announced that she’d be releasing a country album. Immediately after, Holly started an educational series on X, formerly known as Twitter, spotlighting a new Black country artist every day. Her desire to spread awareness about Black country musicians and their history is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of her impact on the country industry.

Enter Black Opry, led by Holly G and co-director Tanner Davenport, which serves as a support system and resource for Black country music fans, industry professionals and artists, such as the Kentucky Gentlemen, Roberta Lee, Julie Williams and others.

“Country and roots music have been made and loved by Black people since their conception,” the Black Opry site reads. “For just as long, we have been overlooked and disregarded in the genre. Black Opry is changing that.”

Launched in April 2021 as a blog with just over 3,000 followers, Black Opry has since grown into “a home for Black artists and Black fans of country, blues, folk and Americana.” Its X account boasts an audience of over 15,000, and the group brings Black talent to stages all over the country.

In addition to community, the site offers playlists and musician profiles for audiences to discover their new favorite artists. Black Opry challenges the idea that Black artists and fans should simply be grateful to be on the country music scene at all ― especially in a genre our forefathers created.

“If we want something that’s gonna be equitable and long-lasting, I think we build our own shit,” said Holly, 34, who is Black Opry’s founder. “We want to have an ecosystem that exists outside of the mainstream that supports these artists.”

On Super Bowl Sunday, Beyoncé successfully broke the internet with just a few words in a Verizon commercial: “OK, they ready. Drop the new music!” Five months after a record-breaking world tour, the Houston native released the first two singles from her album “Cowboy Carter.” Later in February, she made history as the first Black woman to top Billboard’s country charts.

Beyoncé’s foray into country music has ignited a discourse about race and the seemingly lily-white genre. So many questions have bubbled up in the last six weeks: Who gets to be considered “country,” and why? Can the genre, or the American flag associated with it, be “reclaimed”? How did whiteness obfuscate the very Black, very layered origins of country music? Why did it take so long for a Black woman to claim that No. 1 spot?

Beyoncé is using her global superstardom and agency to redefine and rectify a bad experience, one all too familiar for Black artists in country music. In “American Requiem,” the first track on “Cowboy Carter,” she sings: “They used to say I spoke ‘too country’ / Then the rejection came, said I wasn’t ‘country enough.’”

Having donned cowboy hats in the early 2000s and been ridiculed by TV personalities for her Southern accent, Beyoncé is undeniably country at her core — but she shouldn’t be tasked with “fixing” an entire genre, or credited for doing so. The systemic factors that other Black country artists and industry professionals have had to contend with will still exist. But the Black Opry has been trying to fix that.

The reality is that the gatekeepers, aka the centralized authority and voting body that is the Country Music Association, dictate what and who are considered “country enough,” and that’s just one of the many factors limiting the success of Black talent. Moreover, country radio has an intense stronghold in the industry, serving as “the No. 1 source of discovery in country music,” according to Rolling Stone.

Jason Davis via Getty Images

The Black Opry understands that rather than negotiating for a seat at the table within institutions designed to keep country music white, it’s time to build another table altogether. A similar mentality appears to be the impetus for Beyoncé’s “Cowboy Carter.”

In an Instagram post announcing the 10-day countdown to the album, Beyoncé wrote: “My hope is that years from now, the mention of an artist’s race, as it relates to releasing genres of music, will be irrelevant.”

The question is not whether Beyoncé cares to be embraced by the country music establishment, or its fans. As she wrote on Instagram, “This ain’t a Country album. This is a ‘Beyoncé’ album” ― one born out of her desire to “propel past limitations” and transcend genre. The real question is what lies ahead for Black country artists after Beyoncé moves on. (“Cowboy Carter” is the middle installment of a trilogy that began with 2022’s dance record “Renaissance”; fans are already speculating that Act III will be a rock album.)

Beyoncé’s Instagram post also mentioned not feeling welcomed in the country space, likely alluding to her performance of “Daddy Lessons” at the 50th annual CMA Awards in 2016, after which she was the target of hostility from white country fans, conservatives and the industry at large. Online discourse intensified after CMA appeared to scrub all mention of the performance off its platforms. (Following the backlash, CMA denied erasing any mentions of the performance. In a statement to HuffPost, CMA said that it removed an “unapproved” five-second promotional clip prior to the broadcast.)

Davenport, the Black Opry co-director, has been a member of the Beyhive since 2003. He attended that CMA Awards show as a college student. Earlier that day, he’d been tipped off that Beyoncé might be performing, so he ran down to the box office of the Bridgestone Arena in Nashville, Tennessee, and purchased tickets.

Image Group LA via Getty Images

“For your favorite artist of all time to come out and perform in the genre that you’ve always loved as a kid, I was overwhelmed,” Davenport said. “It felt, to me, like a celebration, but within a matter of minutes, that moment reversed itself. To everyone else around me, it felt like they were in danger or something.”

It made sense to Davenport why the Chicks and Beyoncé — Southern women from Texas — were on stage. But it was also clear that white Americans perceived it as an affront to their identity.

“They felt like something that they cherish so much was being taken away from them,” Davenport said. “I vividly remember when I was down there, I was surrounded by majority-white people. I will never forget there being a woman in front of me saying ‘That Black bitch needs to get off stage,’ and me being shocked that that even came out of her mouth.”

Holly said it was a daring decision for CMA to bring “three liberal” Chicks back to country music’s main stage (after they were blacklisted for criticizing then-President George W. Bush). But it’s a testament to Beyoncé leveraging her power to buck industry standards.

Still, if Beyoncé could feel that kind of hostility at the 2016 CMA Awards, what about Black country artists with far less visibility, influence or money?

That’s where Holly and Davenport’s organization has been doing the work. Holly knows all too well what kind of racism and hostility can be found in the country music space. She is a queer Black woman from Virginia, and she has always been drawn to country music.

Like many Black country fans, Holly silently endured concert experiences filled with microaggressions, such as stares from other attendees, Confederate flags flying at various venues, white fans trying to test her country music acumen and other slights. As anti-Black police brutality spurred a “racial reckoning” in summer 2020, Holly witnessed some country musicians begin to pick sides.

“To see all of the people whose music I loved and respected for so long either be silent, or speak against my dignity and humanity as a person, made me feel like I had to figure out a different way to consume country music, or I had to leave it alone,” Holly said.

Erika Goldring via Getty Images

Lately, she and her work with Black Opry have gotten a lot of welcome attention, but she says it’s also been emotionally and mentally taxing to try and discern which parties, especially among the power brokers, are genuine in their interest.

“For my mental health, I had to get off social media completely,” Holly said, acknowledging her inconsistency in posting about Black country artists. “I don’t want anybody for a second to think that we’re not grateful for the opportunity to get not only our story out there, but the names of all the artists that we work so hard for. Because for us, that’s what it’s about. I think all of the artists that we work with are big Beyoncé fans, and so everybody is super excited about that.”

Holly, a former flight attendant, never fathomed working in the music industry, earning a spot in the American Currents exhibition at the Country Music Hall of Fame or sending multiple Black Opry artists to Rhode Island’s Newport Folk Fest, the biggest folk festival in the country.

“It’s just a very insane evolution from somebody who was just a fan of something and wanted to see it be better,” Holly said.

Holly and Davenport first met in person at the 2021 CMAs. They initially connected over Holly’s tweets about Rissi Palmer’s “Color Me Country” radio show on Apple Music, which aired every other Sunday evening. The Grammy-nominated Palmer made history with her song “Country Girl” in 2007, becoming the first Black woman on the country music charts since Dona Mason in 1987.

For Davenport, who was raised in Gallatin, Tennessee, 20 minutes north of Nashville, country music was the backdrop of his life. His mother drove him to school every morning with country music on the radio, listening to Jerry House and the House Foundation on WSIX-FM.

“I remember kind of being in shock that [‘Color Me Country’] had existed, because it was the answer to a question that I’ve had for such a long time: Am I one of the only people of color who likes country music?” Davenport said. “Growing up in school, when I would share with friends that I really loved that new Faith Hill album or a new Martina McBride song, they would look at me like I had 14 heads.”

His love for music and storytelling motivated him to pursue a degree in mass communications from Belmont University and, later, to work for a Christian radio station.

But when forced to either deny his personhood or live proudly as a gay man of faith, Davenport chose himself — and ultimately sacrificed his career. Little did he know that meeting Holly online would result in opportunities much greater, such as managing artists.