Rene Magritte’s L’empire des lumières(1954). Christie’s Images Limited, 2024

[ad_1]

If there is one thing we have learned this year it’s that the collector class still has money to spend, but will only spend it on choicest, most fresh-to-market works. Christie’s 20th century evening sale on Tuesday, which totaled $486 million with a sell through rate of 92 percent by value and 83 percent by lot, certainly proved that maxim true.

The evening opened with 19 lots from the collection of designer and philanthropist Mica Ertegun, which alone brought in $184 million. And while there were moments of drama throughout the sale, often those moments were like a premier league match slogged down by video-assisted referees, plagued by momentum-killing flukes like a dropped call or having to convert currency on the fly.

(All figures reported here include buyer’s premium, unless noted otherwise noted.)

Like last night’s modern art sale at Sotheby’s, which also included a single owner estate sale—in that case, the collection of beauty industry titan Sydell Miller—Christie’s 20th century sale was uneven and slightly erratic, with its fair share of bidding wars and auction records but also an disappointing amount of bid-squeezing and awkward silences. More than 40 percent of the lots hammered at or below their low estimate and 12 lots failed to sell, four of which came in the last six lots of the sale. By that time, most of the people who came to watch had cleared the sales floor for the more inviting environs of their idling black cars or their reserved table at Mr. Chow.

“All this is really about desire,” art advisor Megan Fox Kelly told ARTnews ahead of the marquee sales week. Advisors, she said, try to be rational, provide information, statistics, background, and comparable. “But really it’s all about their desire. I think that’s what we’re going to see this week. People aren’t sitting on their hands right now. There’s confidence. But really it comes down to just a few things, quality of the object, provenance, and desire.”

Rene Magritte’s L’empire des lumières(1954). Christie’s Images Limited, 2024

There were highlights, of course, and that’s where the desire came in. The high watermark was the sale of Rene Magritte’s L’empire des lumières(1954) which brough in almost exactly a quarter of the evening’s total, $121 million, a world record for the artist at auction. The bidding, which bounced around the sales floor and both phone banks before ultimately being won by a collector on the phone with Alex Rotter, the chairman of 20th and 21st century art, lasted a full eleven minutes. You have to hand it to Christie’s for the embrace of spectacle. When auctioneer Adrian Meyer announced the work was open for bidding at $75 million, well below its $95 million estimate, the lights in the room went black. Then suddenly the walls of the sales floor were illuminated with a deep blue, much to the delight of the audience who “ooohd” and “aaahd” like they were at a magic show in the 1920s.

For the last year or so, Magritte has been the art world equivalent of Taylor Swift tickets. There seem to be plenty of popping up, but the price is high, and they are all desirable. Four of the top ten lots from the sale were by the whimsical Belgian surrealist, one of which happened to be another L’empire des lumières, though this example, which was from 1956, was smaller both in size and in price. It sold for $18.8 million against an estimate of $6 million to $8 million. Like many of the lots during the sale, the mini-Lumières went to a buyer on the phone with Christie’s deputy chairman, Asia Pacific, Xin Li-Cohen, hopefully signaling a reactivated Asian market. After this evening she deserves a shoulder massage after having had her arm up, either bidding or covering her mouth as she spoke to a collector, for what seemed like more than half the lots in the sale.

Ed Ruscha’s absolutely stunning 1964 Standard Station, Ten-Cent Western Being Torn in Half, which also received the dramatic light show treatment, this time in a sci-fi-ish red, held the number two slot on the evening’s top ten list, bringing in more than $68 million on an estimate of around $50 million. (That was a new auction record for the artist.)

Works by Alberto Giacometti, Joan Mitchell, David Hockney, and Willem de Kooning rounded out the top seller list. It’s notable that the two Mitchells, City Landscape and Untitled (both from 1955), hammered at below the low estimate while also counting among the most expensive works sold. Auction math is a funny thing.

Joan Mitchel, Untitled (1955). Christie’s Images Limited 2024.

Also notable are the works that were passed on, which included marquee names like Jasper Johns, Henri Rousseau, Georgia O’Keeffe, Wayne Thiebaud, and Gustave Caillebotte. Given the political environment during what I like to call the auction houses’ harvest season, it’s no surprise that there were some subpar works in the mix, along with the museum-worthy Magrittes and the Ruscha.

“Both sales were solid, while perhaps uneven in quality,” art advisor Mary Hoeveler told ARTnews after the sale, referencing Sotheby’s Monday night sale on Monday night and Tuesday’s at Christie’s. “Christie’s kept the estimates low to not only encourage bidding, but to see where the market is. There is steam behind the market again, and once people see that, more and better works will show up. Next season the consignments will start to flow again.”

At a press conference after the sale, Rotter said that Christie’s was operating under the “masterpiece approach” for this sale.

“In a market that is not so easy to maneuver, we thought that if we present the greatest works we can get, the Magritte, the Ruscha, these are the best examples. Now, there were things that didn’t sell. There were casualties. But I’m not worried about it,” he said. “The works that we put all the emphasis behind really proved us right. They had multiple bidders and showed that a market based on individual taste is on the rise.”

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

Sallyann Corn always knew that she would end up in a profession where she could utilize her imagination and translate ideas into forms. Growing up in a small town, however, meant that she had only heard of three potential tracks: art, architecture, and fashion. Her interest in clothing then led to an exploration of visual merchandising. But when she switched to an industrial design program in college there was an immediate click. “I knew that was exactly the path meant for me,” Corn says. “It felt so all-encompassing, and it has allowed me the freedom to pursue many mediums, scales, and project types.”

In 2008, Corn founded the Seattle-based studio fruitsuper with Joe Kent. Partners in business and life, the duo’s collaboration emphasizes playful simplicity, spanning a range of arenas from products to physical environments and curation.

Yet the pair not only caters to individual clients, they also welcome the public to join in and experience the energy for themselves. Their retail space and wine bar in Pioneer Square serves as a neighborhood hub, featuring fruitsuper’s signature items alongside pieces by other makers from across the United States. It is here that the team hosts rotating exhibitions, panel discussions, gatherings, and private events. These endeavors are part of fruitsuper’s ultimate mission – to celebrate a diverse and growing independent creative community.

With jobs and the day-to-day often intertwined, at times it has been challenging to maintain a healthy balance, especially when Corn and Kent had one shared space for all of their activities. Even with the separate studio they have today, the couple still finds easy ways to help make the switch from work mode to down time, like lighting candles or changing outfits.

There’s one element, however, that remains essential, and offers endless inspiration. “Travel is imperative to our practice, because it immediately makes us see the everyday in a new way,” Corn notes. “Objects as simple as toothpaste, traffic signals, and garbage cans surprise and delight us.”

Today, Sallyann Corn joins us for Friday Five!

Photo: Kunihiro Fukumori

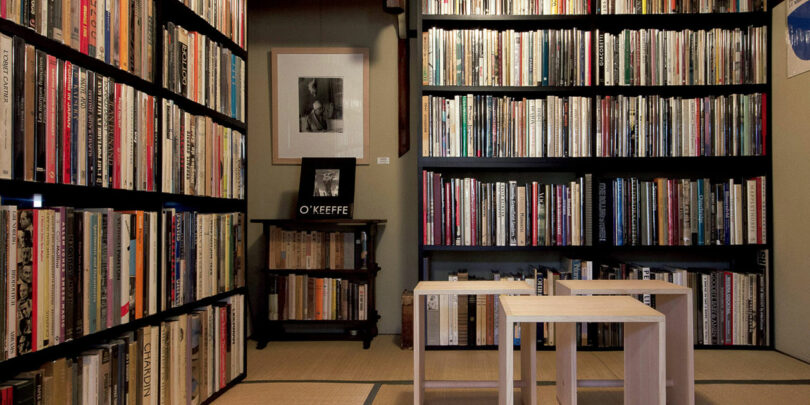

To label us “Book Lovers” would be an understatement. We love to scour, hunt, and bury ourselves in local bookstores, no matter what city we’re in. We find that a small, independent bookstore with teetering stacks and narrow paths truly showcases the unique voice of each store owner and their city. We never shy from purchasing books while traveling, as we’ve found some of our absolute favorite literary treasures around the globe. A few of our favorites: Arcana Books (Los Angeles), Book/Shop (Oakland), Books & Things (Kyoto), Booklarder (Seattle), Casa Bosques (Mexico City), and Monograph Bookwerks (Portland).

Photo: Courtesy of Baisikeli

We’re less spandex-wearing and gear-focused and more the bells and baskets, stop-when-we-see-a-wine-bar type of bicycle riders. But we find nothing more exciting than renting bikes to explore new areas. During travel and at home, we love to find a neighborhood spot that provides bicycle rentals; as they’re almost always far better quality bikes than hourly rentals and often come with personalized route suggestions, bike adjustments and favorite neighborhood tips. Renting a bike for a day allows us to cover so much more ground and explore more than we ever could on foot. And always provides a much deeper connection to new neighborhoods than jumping in a car or on public transportation.

From a dry cedar sauna to natural hot springs, inside or outside, we love a soak/steam it out session. It’s such a meditative and restorative activity! We love that it essentially forces you to be nothing but present; no phones, books or other distractions can be involved. So your only focus is on your breathing, your sweat, your thoughts and your company. It’s incredibly invigorating!

For years I was foolish enough to not make time for walking. But now that I’m in the habit, I find myself less able to focus and be productive if I haven’t gone on at least two long walks each week. My commute from home to our studio or shop is around 3 miles and takes me about one hour. I’m not a headphone wearing person, so this hour of solitude is fantastic and now integral to my creative practice. I’ve found that I now arrive at work with a clear head and I’m much more prepared and ready to start my day. Between weather shifts and route options, it feels like endless choose-your-own adventure paths that lead me to new observations in places I’ve walked by dozens of times before. Two favorite walking spots that provide endless inspiration are the Myrtle Edwards Park/Olympic Sculpture Park in Seattle and the Highline in NYC.

Photo: Studio Fræ

For the past 3 years we’ve been fortunate to participate in DesignMarch in Reykjavik. We’ve fallen in love with smaller (by comparison to Milan, NYC, etc.) art and design festivals. The scale of these smaller/shorter festivals feels far more manageable and the work feels less dominated by large corporations and budgets and instead filled with young, independent, fresh work. We love seeing what can be created and presented with the constraints of smaller budgets and limitless enthusiasm.

fruitsuper SHOP 2019-present A gift shop and wine bar Photo: Brooke Fitts

Sculptures for Books 2024 A collection of objects designed for page holding, placemaking, and in celebration of books. Photo: Brooke Fitts

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

Longwood Gardens, one of the largest and most historic gardens in the US, is unveiling a years-long expansion and renovation on 22 November. The $250m project has transformed the vast public space consisting of more than 1,100 acres of gardens, woodlands and meadows in south-eastern Pennsylvania. Notably, this includes the careful reconstruction of the late Brazilian artist and landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx’s 1992 cascade garden, which had fallen into disrepair in the past three decades.

Longwood has a storied history. For thousands of years the Lenni Lenape tribe hunted and fished on the land, before they were forcefully removed from Pennsylvania in the 18th century (related artefacts, like quartz spear points, have been found throughout the property and are displayed today in Longwood’s Peirce-du Pont House). A Quaker farmer named George Peirce purchased and cleared more than 400 acres of the land in 1700; a brick farmhouse built by one of his sons in 1730 still stands today. Peirce’s heirs were curious about natural history and began planting wild and rare specimens on the grounds, creating an arboretum that covered 15 acres by the mid-1800s. But the family eventually lost interest in maintaining the property, and the arboretum began to deteriorate. In 1906, the industrialist Pierre S. du Pont purchased the land to save its trees from being sold for timber. Over the years he facilitated the creation of extensive gardens, which he opened to the public in 1921, as well as a foundation to oversee a series of expansions and additions—including a famous 600-jet fountain that puts on choreographed water shows. Longwood was added to the US’s National Register of Historic Places in 1972.

The gardens’ most recent revamp was spearheaded by the architecture firm Weiss/Manfredi in collaboration with the landscape architects Reed Hilderbrand, who worked with the Burle Marx Landscape Design Studio to oversee the transfer of the cascade garden to an enlarged custom glasshouse. The cascade garden comprises 16 waterfalls that flow into a pool, framed with climbing vines and clusters of striking bromeliads. Most of the original plants have been replaced over the years, as some had grown too tall for the glasshouse and were crushed against the ceiling; others were badly burnt due to poor climate control.

Sharon Loving, Longwood’s chief horticulture and facilities officer, was there when Burle Marx completed his original garden, recalling that it was “like watching a magician work”. Burle Marx, who died only two years after completing the cascade garden, had first made connections with Longwood’s trustees through a Pennsylvania-based liaison in the late 1980s. Some of them travelled to Rio de Janeiro to observe how Burle Marx worked. It was first proposed that he design the East Conservatory at Longwood, but that project fell through, as his studio felt that Burle Marx’s Modernist approach to landscape design would not be appropriate for the space. Instead, he opted to construct a cascade garden inside a 3,500 sq. ft former desert glasshouse with a 22ft ceiling.

“He arrived and did not follow the planting plan as closely as we anticipated,” Loving says. “We were asked to source enough plants to fill the house twice. He would walk around the space, sometimes taking us by the arm, or lie down in the shade. Then he would instruct the whole team to grab plants and would begin ‘painting’ the plants on the wall, telling us this one should go here or there. It was very intuitive and organic. He said he saw the project like the crescendo of a symphony. He wanted it to be powerful, where you would have the sound of water and all your senses would be engaged. He combined his plant knowledge, his skill as a landscape architect and all of his expertise in music and art when he worked.”

The $6.5m revamp of the cascade garden involved updating its mechanical and fountain systems to stabilise climate, resetting most of the original schist of the planting beds and garden walls, and reinstalling around 180 plants salvaged from the original glasshouse. It also lifted the peak of the garden to a height of 30 ft and expanded its overall footprint to 3,800 sq. ft, adding additional plants to give it the “rainforest experience” that Burle Marx had envisioned. A central path and ramp were also constructed for accessibility.

Burle Marx’s concept drawings, construction design, planting plans and later 3D scans of the original cascade garden, which are held in Longwood’s permanent collection, greatly informed the project. The architects also worked with Anita Berrizbeitia, a landscape architect and Burle Marx scholar, to outline the most significant features of the garden. A series of workshops followed to decide which parts of the garden could be changed and which should be closely reproduced.

“We knew the garden would need to be dismantled, and realised how important it was to tread lightly and carefully,” says Kristin Frederickson, a co-founder of Reed Hilderbrand. “Reconstruction assumes that a garden has been lost and will be rebuilt, while preservation assumes a garden is in place and you’re protecting it. This was somewhere in the middle.” She adds that a point of importance was retaining the “sense of immersion as the changes were executed”.

Reed Hilderbrand was instrumental in consulting on the cascade garden’s long-term conservation, assisting with fine tuning the design in collaboration with Weiss/Manfredi, which sought to create “a new home for the garden where it was not only better located but also environmentally and architecturally much more conducive to the beautiful work that Burle Marx did”, says Marion Weiss, a cofounder of Weiss/Manfredi.

Together with the cascade garden, a centrepiece of Longwood’s expansion and renovation project has been the addition of the West Conservatory—a 32,000 sq. ft space said to be one of the largest in the US, containing several gardens, pools, fountains and nearly 2,000 glass panels. Like Burle Marx’s garden, the conservatory is a “living and breathing” glasshouse, according to Longwood, with automated walls and roof panels. Longwood has also added 17 acres to its gardens, an education and administrative building, a bonsai courtyard, a renewed seasonal restaurant and other features.

Longwood will hold a design symposium in October 2025, bringing in representatives from Weiss/Manfredi and Reed Hilderbrand as well as other speakers, to discuss Burle Marx’s legacy and impact on 20th-century landscape architecture and the importance of the cascade garden—his only such surviving work in the US.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

By the turn of the 20th century, New York’s skyline was changing fast, and architects and builders were competing to reach the skies. The city was in the midst of an economic boom, and with the development of steel-frame construction, this period marked the beginning of a skyscraper race, as corporations sought to showcase their prestige by erecting taller and more visually striking corporate buildings. Among these was the Flatiron Building.

Rising at the intersection of Fifth Avenue and Broadway, the Flatiron was a departure from the traditional box-like shapes dominating the city’s architecture. Designed by architect Daniel Burnham, its striking 22-story-high, wedge-shaped structure soon became an iconic architectural site, even appearing in Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man trilogy, symbolizing New York’s architectural heart as the office of the Daily Bugle.

A steel skeleton, one of the first to be used, enabled Manhattan’s Flatiron Building to become the tallest building in the world, approximately 300 feet high, at the time of its completion. Photo by Charles R. Ritzmann/Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images.

Nicknamed the Flatiron for its resemblance to a clothes iron, the building was inaugurated in 1902 and instantly captured public attention. It wasn’t just a new addition to New York’s geography; it was a bold declaration of architectural ambition and ingenuity.

Close view of ornament on the building exterior of Flatiron Building in New York City. The Flatiron Building, originally the Fuller Building, is a steel-framed landmarked building located at 175 Fifth Avenue in the Flatiron District neighborhood of borough of Manhattan, New York City. Photo by: Sergi Reboredo/VW Pics/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

At 285 feet tall, it was one of the first skyscrapers built with a steel frame, enabling the building to withstand the powerful winds that barreled down Fifth Avenue. Burnham trained in Beaux-Arts architecture, and chose to adorn the Flatiron’s slender façade with glazed terracotta and limestone details, creating an intricate exterior that drew even more intrigue to its unconventional shape. The building was initially known as the Fuller Building, as it housed the headquarters of the Chicago-based Fuller Company.

New Yorkers were initially skeptical of the Flatiron’s design, and critics predicted it might collapse. The New York Tribune deemed it “the greatest inanimate troublemaker in New York.” At the time, steel-frame construction was met with caution by the general public, who feared that such tall, slender buildings might not be stable. The Flatiron’s slender triangular shape created powerful winds, known as the “Flatiron breeze” which only heightened the building’s fame. However, Burnham’s architecturally daring structure proved strong.

Jeffrey Gural [L] and Jacob Garlick [R] at the auction of the Flatiron Building on 22 March 22, 2023. Photo: Christina Horsten via Getty Images.

Today, the Flatiron Building is entering a new chapter. For years, scaffolding has shielded its silhouette as restorations took place, but soon the building may shed its purely commercial past. A group of owners have submitted plans to convert the Flatiron into luxury apartments. If approved, the renovation would introduce New Yorkers to a unique residential opportunity. The building’s surrounding neighborhood, fittingly called the Flatiron District, has evolved and grown alongside the building, transforming from a commercial area into one of New York’s most lively areas, filled with high-end restaurants, boutiques, and cultural landmarks.

The Flatiron has woven itself into the identity of New York City, its once-mocked structure is now a celebrated landmark. Decade after decade, it stands as a testament to the idea that bold architecture can reshape a city’s character, and proves that true icons are those that dare to stand apart.

Even the world’s most ambitious structure began with a humble plan. In Blueprint, we drill down to the foundations of dream homes and iconic buildings to explore how architects and designers brought them to life.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.

[ad_2]

Source link

“Could the Hirshhorn be a major institution? These days, Director Melissa Chiu says it should assume its role as ‘the national museum of modern and contemporary art.’ The notion would have invited laughs in 1974.” – The Washington Post (MSN)

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

Dallas-based mega-collector Howard Rachofsky, a former hedge fund manager and fixture of ARTnews’s Top 200 Collectors list, is teaming up with a collector some 40 years his junior, Thomas Hartland-Mackie, to start The Warehouse Dallas Art Foundation, a non-profit arts foundation at The Warehouse, an 18,000 square foot exhibition space in a former storage facility that Rachofsky opened in 2012.

The new foundation, which, according to a statement, has been formed to ensure an educational mission of both collections, will officially debut in February with an exhibition of works from both collections. Admission will be free.

Rachofsky has long been a fixture of the Dallas art scene and a fan of collaboration. In 2005, he and his wife Cindy were one of several prominent collecting families in the city that pledged to donate their entire collections to the Dallas Museum of Art up their death. (Rachofsky also promised the museum his home, designed by starchitect Richard Meier.) Rachosfky co-founded The Warehouse with fellow collector and DMA board member Vernon Faulconer; the space showed both of their collections until Faulconer’s death in 2015.

“There were a lot of ideas that I had that I couldn’t execute or wasn’t in a position to,” Rachofsky told ARTnews in a joint interview with Hartland Mackie. “And, being pragmatic, I just turned 80. That’s not old anymore, but it’s not young. The Warehouse and places like it—that really offer opportunities to meet artists, to meet curators, to explore ideas institutionally—is pretty difficult to do.”

Rachofsky’s collection, accumulated over decades, numbers some 1,200 artworks, primarily by American and European post-war artists. Hartland-Mackie, meanwhile, began collecting over ten years ago. Like Rachofsky, has served on the board of the DMA. As CEO of the Labora Global Ltd., he oversees his family’s investments and philanthropic activities; he collects art in collaboration with family members and has built the Hartland & Mackie/Labora Collection, which now consists in 300 contemporary artworks.

Under the umbrella of The Warehouse Dallas Art Foundation, Rachofsky and Hartland-Mackie will use the exhibition space to show works from both of their collections, as well as artworks borrowed artists and from other collections, and put on shows from outside curators.

“In our way we are helping to bring more of the art world to Dallas, which Howard has already been instrumental in doing,” Hartland-Mackie said.

The foundation had a soft opening during last week’s Two by Two auction, an event the Rachofskys have held in their home for the past 25 years that benefits both the Dallas Museum of Art and amfAR. (This year’s event, however, was the last, and it went out with a bang, with Alan Cumming as host and a performance by Chaka Khan.) Curators from the DMA organized an exhibition at The Warehouse celebrating 25 years of Two by Two, made up of works the museum has acquired with funds from the benefit auction over the years.

In February, The Warehouse Dallas Art Foundation will have its official debut, with an exhibition of works from Rachofsky and Hartland-Mackie’s collections that will include pieces by Anicka Yi, Wade Guyton, Cavin Marcus, Rashid Johnson, Dana Schutz, Philippe Parreno, Pierre Huyghe, Marguerite Humeau, Carrol Dunham, and Howardina Pindell, and will be curated by Hartland-Mackie’s art adviser Benjamin Godsill and Thomas Feulmer, The Warehouse’s in-house curator. There will also be, as Rachofsky put it, “a little influence from Thomas and I to put some seasoning on it.”

Hartland-Mackie said his passion for Dallas comes from living there during college and for some years afterwards. He has since moved to Costa Rica with his family, but his mother lives in Dallas. “It’s got a great group of people who are tremendously philanthropic in the arts,” he said. Two by Two, he added, was one of the things that inspired him to start an art collection. “It was a way for me to see amazing artwork and get to understand a little bit more about that world, and start to buy some art in a way that felt like, Okay, I’m supporting some great artists, but I’m also supporting great causes. Through that, I built a relationship with Howard and started to learn from him.”

Rachofsky and Hartland-Mackie went on to buy artworks together, which Rachofsky characterized as “usually installation-based, works that were difficult to house.” Hartland-Mackie said he is looking forward to using the Warehouse to show precisely those kinds of works.

“As stewards of these artworks, it makes me sad that we have so much work in storage and in some cases has sat there since I acquired it,” Hartland-Mackie said. “Things that are hard to show in domestic settings. I have this amazing Philippe Parreno Christmas tree that we can’t wait to install at some point.”

The collectors emphasized that education will be a big part of the foundation’s mission. Caitlin Overton, who oversees education for The Warehouse, will work for the foundation on community outreach as well as schools.

“The idea of the foundation is really to give [the collection] a long-term future, an indefinite future, if you will and not to just terminate when I’m terminated, so to speak.” Rachofsky said.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

Japan has long been revered for its deep-rooted dedication to craftsmanship, where the pursuit of perfection through repletion is not just a practice but a generational ambition. This idea is particularly familiar in Shizuoka City, a former castle town that became a vibrant hub for artisans around 400 years ago. Honoring this rich heritage, Japanese design studio UO created the bold sculpture Nakajimaya Crossing in the lobby of the century-old Nakajimaya Grand Hotel. This dramatic installation, accompanied by smaller objects and a façade design to greet visitors, visually celebrates four types of crafts, as well as innovative combinations of these techniques, all elegantly framed within elongated metal structures.

The installation features metal frames that stack and layer to form a central tower in the lobby, as well as four wall-mounted pieces behind the front desk. These frames create a series of intersecting shapes and half-moons that each highlight a different traditional craft. Where the frames intersect, unique blends of two crafts are displayed, illustrating an innovative fusion of artisanal techniques. For example, at the intersection of a frame showcasing fabric dyed with tea leaves (a technique called “ocha-zome”) and another featuring precisely arranged 2mm bamboo strips (“take-sensuji”), a three-dimensional textile emerges, intricately woven from both dyed fabric and bamboo.

This project not only showcases the merging of diverse crafts but also represents an extraordinary collaboration among four craftsmen, each typically working independently within their distinct disciplines. Facilitated by UO, these artisans were challenged to step beyond the boundaries of their individual skills, learning from one another to create new and inventive technical expressions.

Guided by Nakajimaya Crossing as the project’s centerpiece, the hotel plans to extend this concept beyond the sculpture, integrating these combined techniques into furniture, room keys, and other elements to craft a cohesive and immersive visual identity throughout the guest experience. As a permanent fixture at the Nakajimaya Grand Hotel, Nakajimaya Crossing not only redefines traditional craftsmanship but also symbolizes the hotel’s role as a gathering place for diverse skills.

To learn more about Nakajimaya Crossing by UO, visit uo-design.jp.

Photography by Keita Otsuka, featured photo by @hikimonojo639_official

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

More than three years after announcing the imminent opening of Leonora Carrington’s former home in Mexico City as a public museum, the university in charge of the project has scrapped the idea, intending to use the house as a research centre instead. According to Carlos S. Maldonado of the Spanish newspaper El País, the museum may have been nixed due to a labour dispute at the Metropolitan Autonomous University (UAM), although the university denies this.

The impetus for turning the late Surrealist painter’s house into a museum—à la Frida Kahlo’s Casa Azul—came from Carrington’s younger son Pablo Weisz Carrington, who took on the project after her death in 2011. Weisz Carrington sold the house, along with a loan of 8,000 of the artist’s objects, to UAM in 2017 with the understanding that it would eventually be opened to the public as a museum. UAM invested roughly $600,000 into the museum, and teased its public opening in 2021.

UAM justifies its pivot on Carrington’s home from public museum to research centre by saying that it is a logical step for a university. Union leaders at UAM are sceptical of this explanation. The union points to the fact that, in accordance with its contract with the university, it had asked for 17 additional jobs to staff the new museum in 2021. These were never created. Some also point to a perceived lack of interest from UAM’s leadership to continue with the museum project.

The cancellation of the museum is perhaps ill-advised given Carrington’s recent rise in popularity both in the art market and among the general public. The artist has been front and centre in this year’s celebrations of the 100th anniversary of Surrealism, and her painting Les Distractions de Dagobert (1945) set a record for her work in May when it sold at auction for $28.5m.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

Meow Wolf lovers, set your dials to Radio Tave. The art and entertainment company’s latest outpost has touched down in Houston, Texas, and it’s an art-filled, interdimensional adventure through time, space… and community radio.

Opening on Halloween, Radio Tave is the fifth permanent exhibition from Meow Wolf, which tapped into the zeitgeist for immersive art when it opened its interactive, photo-friendly House of Eternal Return in Santa Fe in 2016.

Soon, investors were rolling in, and the offbeat art collective was morphing into a serious company. There were growing pains along the way—a lawsuit from a contributing artist, layoffs during the pandemic (and again earlier this year), a successful unionization effort, and the untimely death of cofounder Matt King.

But Meow Wolf’s expansion has brought its experiential, otherworldly magic to Las Vegas (Omega Mart, 2021), Denver (Convergence Station, 2022), Dallas Grapevine (the Real Unreal, 2023), and now Houston, with a Los Angeles opening planned for 2026.

The entrance to Meow Wolf Radio Tave in Houston. Photo by Arturo Olmos, courtesy of Meow Wolf.

Over the next year, CEO Jose Tolosa told me that the company is projecting a total of 3 million visitors across all five sites—not too shabby for what was once a band of lovable weirdos that famously chose its nonsense name from a pair of random words drawn from a hat.

Tickets start at $40, but you can also buy a new “Portal Pass” for unlimited visits for a year for $84, as well as discounts for food, drinks, and merchandise, and exclusive content on the new Meow Wolf app. (“You’re going to get a lot of very special privileges,” Tolosa said.)

Janell Langford’s Obsidiodyssey installation at Meow Wolf Radio Tave. Photo by Tarick Foteh.

If you don’t know what the deal with Meow Wolf is, it’s all about the unseen, strange, and fantastical lurking just beyond our frame of vision—until these alternate dimensions suddenly converge on our otherwise humdrum reality. It’s a place where artists can run wild, adding their own personal touch to a high-tech art playground that can’t help inspire a sense of whimsy and wonder in its viewers.

In Houston, the jumping-off point is a humble community radio station, with visitors entering the dated-looking Little Thicket, Texas, headquarters of Radio ETNL. (It’s inspired by KMRD, a thriving community radio station in the 250-person town of Madrid, New Mexico.)

But it soon becomes clear that the station has become unmoored from our familiar universe. You’re only in the space for a moments before things start to get weird.

The entrance to Radio ETNL at Meow Wolf Radio Tave in Houston. Photo by Arturo Olmos, courtesy of Meow Wolf.

“This is our known before we venture off into the unknown,” senior creative producer Susie Cowan told me at the Radio Tave press preview.

Opening filing cabinets can reveal strange monsters. There are signs warning staff that no one is really sure what’s going on inside the all-gender bathroom anymore. The floor tiles in the break room seem to be warping before your eyes, and opening the refrigerator reveals an office hallway, utterly nondescript—save for the fact that it shouldn’t be there at all.

“The fridge is such a great metaphor. You open something familiar, and there is something so unexpected that can lead you in any direction,” Sarah Bradley, a senior creative director, said.

Radio ETNL at Meow Wolf Radio Tave in Houston. Photo by Tarick Foteh, courtesy of Meow Wolf.

And then there’s the radio broadcast itself, playing throughout the offices, which gets stranger the longer you listen. Eventually, the lights start to flicker as a strange transmission comes in over the airwaves, signaling the collision of parallel worlds. The radio DJs, it is revealed, have become “tavers,” short for travelers between universes, untapping our latent ability to access these hidden portals.

Radio Tave is set to be the anchor tenant in a new mixed-use development from the Deal Co., a Houston real estate company, at the former Moncrief-Lenoir Manufacturing sheet metal factory in the city’s Fifth Ward.

Jasmine Zelaya with her art installation at Meow Wolf Radio Tave. Photo by Sarah Cascone.

Meow Wolf has utterly transformed its portion of the historic space, with a soaring two-story entry lined with artist murals leading to a faux stained glass window of the Little Thicket radio tower. A darkened hallway, offering a moment of sensory calm before the storm, leads you from there inside the experience.

There’s also Meow Wolf’s first in-universe restaurant, a queer take on the southern dive bar called Cowboix Hevvven conceived by longtime Meow Wolf artist Cole Bee Wilson. A touching tribute to King with rainbow angel wings sits at the counter, getting a drink from the proprietor, who Wilson described as “Ancient Demi god of blood and fire who has retired to run this bar.”

Cowboix Hevvven at Meow Wolf Radio Tave in Houston. Photo by Arturo Olmos, courtesy of Meow Wolf.

By this point, Meow Wolf has definitely established a formula, with familiar beats that recur across different locations.

The fridge portal is a classic, originally from the OG Santa Fe exhibition, as is the Gloquarium, a black-lit coral forest originally conceived by King that has sprouted up in one of the radio station offices. There is a central performance venue with a stage, and a balcony level ringed with colorful murals by different artists. And every Meow Wolf I’ve been to has had a city street, seemingly plucked out of some dystopian sci-fi film, and a mysterious forest.

An office at Radio ETNL merges with the Gloquarium at Radio ETNL at Meow Wolf Radio Tave in Houston. Photo by Arturo Olmos, courtesy of Meow Wolf.

Increasingly, there are also little Easter eggs sprinkled about tying together the disparate locations, like Radio ETNL reporting about the Zalg harvest—an Omega Mart product—in its “multiversal farm report.” (The audio is a huge part of the experience throughout, with instruments visitors can play to add to the underlying musical score, and dynamic layers of sound generated by software that change cued to the lighting and other effects.)

But what makes each subsequent location unique is Meow Wolf’s commitment to working with local artists and incorporating their work into the maximalist display. There are 50 Houston artists, including the well-known Trenton Doyle Hancock, who shows with New York’s James Cohan gallery.

To tap directly into the Houston artist community, Meow Wolf hired local graffiti pioneer Mario Enrique Figueroa Jr., or GONZO247, as he is known, to serve as the project’s artist liaison.

The performance venue at Meow Wolf Radio Tave in Houston. Photo by Arturo Olmos, courtesy of Meow Wolf.

I met with GONZO at Luckie’s Pocket, a historic 1918 schoolhouse named after Black educator Charles W. Luckie, which he is in the process of transforming into a nonprofit art center celebrating the history of street art in Houston. That includes the “Wall of Fame” in the backyard, which in the early 1990s, thanks to GONZO, became the city’s first legal graffiti wall.

“When you walk through Meow Wolf, you’ll get a really good sense of representation of what Houston is—the homegrown people who were born and raised here, but also so many people who have come from other cities, other states, and other countries to make a life here,” he told me.

Garrett Clayton and Mario Enrique Figueroa Jr., or GONZO247, at Luckie’s Pocket, a nonprofit art center they are opening at a historic Houston schoolhouse. Photo by Sarah Cascone.

GONZO’s role didn’t officially involve making any art for Radio Tave, but in the end he couldn’t help himself from sneaking tags onto some of the blank spaces between different installations.

“I came in overnight and just kind of did my thing,” he said. “The next day they were like, ‘I think we got vandalized! What is that?’ That’s the feel I want!”

I also did a studio visit with Falon Mihalic, a landscape architect who runs her own design firm and has done permanent public art installations in Miami and Houston.

Falon Mihalic, a Houston artist who created an installation titled Abandoned Garden for Meow Wolf Radio Tave in her studio space. Photo by Sarah Cascone.

Her Abandoned Garden piece at Meow Wolf is Mihalic’s first major indoor project, incorporating painting, porcelain ceramics fired with colorful glazes, and photographs of native Houston plants. It’s inspired by all the major storms she survived during her childhood in the Florida panhandle, an imagined ecology that was flooded and forgotten.

“The garden persists,” Mihalic said. “Even after whatever climate events are in our future, the landscape will still be here.”

To install the work, the Meow Wolf team suggested a two-part epoxy it often relies on for safety reasons, because it is fire-rated. But for Mihalic, the material was an exciting for creative reasons: “It’s a new thing in my tool box! You can make ceramics combine with other stuff, and you can pigment it and texture it,” she said.

Patrick Renner with an interactive art installation he is building in Houston. Photo by Sarah Cascone.

Creating a piece for Meow Wolf can not only open new avenues of exploration for artists. It introduces them to new audiences, and potentially new career opportunities, sculptor Patrick Renner pointed out as he walked me through an in-progress site-specific art installation he was building using salvaged wood.

The piece, titled Groundswell, is set to open next month in an informal gallery space in the lower level of the home of his friend, artist Michael Sean Kirby. Now here I was, a New York art journalist coming to see it. (The work will be an undulating platform that fills an entire room, and people will be able to walk across it.)

These interactive sculptures at Meow Wolf Radio Tave play musical tones when you touch them. Photo by Tarick Foteh, courtesy of Meow Wolf.

Renner’s Meow Wolf project, Sync Whole, is quite different: a small chamber with glass vitrines lining the walls, filled with layers of geological strata. The artist turned to his stash of found materials, thinking the installation, which weighs a whopping three tons, would be a good opportunity to clear out various odds and ends from the studio.

“I ended up finding new things, so I basically broke even,” Renner admitted.

Houston artist Brian Dibala, known as Neon Thrash, with his Meow Wolf Radio Tave installation. Photo by Sarah Cascone.

In addition to the local talent, Meow Wolf has some 50 full-time artist employees, known as the Art Team Task Force, led by manager Laura Davidson. In Houston, they worked together to bring the entire exhibition together, and to create the “Amalgam” space, a soaring two-story tunnel of, well, amalgamated odds and ends, made from found materials.

Meow Wolf has come a long way from its art collective beginnings, turning piles of trash and discarded materials into fantastic installations in Santa Fe warehouses. But while the resources have grown and production values and technological capabilities have improved, staff members maintain that a wild creativity still fuels the project.

The Art Team Task Force built the Amalgam at Meow Wolf Radio Tave. Photo by Tarick Foteh, courtesy of Meow Wolf.

“A lot of that same spirit of dumpster-diving and working together to see where things go was a big part of this room,” Davidson said. “The majority of the people on the art team task force were members of the collective before Meow Wolf was a company.”

Meow Wolf’s Radio Tave will open at 2103 Lyons Avenue, Houston, Texas, October 31, 2024.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

The Pig Iron School for Advanced Performance Training will become part of Rowan University in New Jersey, almost four months after it was cast adrift following the sudden closure of the University of the Arts in Philadelphia.

Pig Iron Theatre cofounder Gabriel Quinn Bauriedel said Rowan will be the Pig Iron School’s forever home.

“I believe absolutely that this is phase three of the school,” he said. “Phase one we did it on our own. Phase two we did it with UArts. Phase three, the final phase, is with these gentle, kind, wise folks at Rowan.”

The Pig Iron Theatre Company is widely known for its experimental and devised theater techniques and created a school to train students at the master’s degree level. But the degree program requires an institutional partner, which is now Rowan.

Rowan University has three campuses in South Jersey, with the Department of Theater and Dance based on the main campus in Glassboro, New Jersey. Pig Iron will remain in Philadelphia, with students studying at the school’s studio in Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood.

“It’s really a unique opportunity to have this exemplary, unique MFA that’s already in existence,” said Rick Dammers, dean of the College of Performing Arts at Rowan University. “They have their own facilities. They have their own students already. It’s a lot easier to incorporate a pre-existing program than to start one from scratch. And the reputation of the program, too, is exciting.”

[ad_2]

Source link

VSO Union members said two-plus years of bargaining is too long, and that the museum hasn’t provided meaningful counters on its economic demands, including a $27/hour starting wage, scaling pay rates, health care expansion for part-time workers, and reinstatement of employer retirement matching. – Seattle Times

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

“Hi, I’m Parker Finn. I am the writer, director and one of the producers of “Smile 2.” This scene takes place in the back half of the film, and we are with the character of Skye Riley, a pop star played by Naomi Scott. She’s the main character of the film. And we are jumping into this scene when she is at a peak level of paranoia. So in this scene, Skye is encountering this group of smilers. We’d never done a full group before. It felt like a really exciting new thing to do in this film. So this moment when they are chasing down the hallway after her. My production designer, Lester Cohen, and I had designed this mirrored hallway because we knew that by sending this horde of dancers down the hallway, all the reflections was going to exponentially grow the amount of faces and arms and limbs we see. These dancers that I got to work with and my choreographer, Celia Rowlson-Hall, it was this incredible collaboration to create something that felt both like a menacing attack, but also at the same time dance. For the bulk of the scene, we had 14 dancers and they’re all performing this choreography, but they all also had to be employing the smile throughout. So it was really about coaching them, how to do the smile, but also how to hold onto it while doing all of this movement. But also how we have Naomi, who is performing choreography, but for her to make it look not like choreography, like she’s just suddenly being attacked and doesn’t know what’s going to happen next.

[ad_2]

Source link