Long-standing partnership leads to new public, nature-based … – Mississippi State University

[ad_1]

Long-standing partnership leads to new public, nature-based ... Mississippi State University

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

Long-standing partnership leads to new public, nature-based ... Mississippi State University

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

The arrival of Christopher Columbus and the conquistadors in the Americas led to the destruction of empires and civilisations and the deaths of millions in the new world – not by war, but from the waves of diseases that travelled from the old world to the new. Human contact took smallpox, plague, typhus and measles to the new world and brought syphilis to the old. It also led to the traffic of plants and animals, precious metals, populations, commodities and ideas from one side of the world to the other. The effects of exploration and conquest, migration and colonisation, in what has come to be called The Columbian Exchange, are too many to catalogue. It changed everything and is certainly too much to unpack here, on a gallery wall-panel or even in a 50-minute film by John Akomfrah, whose hugely ambitious art always gives the effect of running away with itself. Arcadia, presented on five screens butted together in the form of a cross, glosses a history of these fateful transactions and consequences in a constantly unfolding series of vignettes, choreographed tableaux and montaged footage culled from many sources. Keeping up is hard to do.

On 16 September, 1620, after many delays, the Mayflower, with its 102 pilgrim passengers, set sail from Plymouth for America, landing on Cape Cod in early November. For the 400th anniversary of this journey, Akomfrah – who is set to represent Great Britain at next year’s Venice Biennale – was invited to make a film, originally scheduled to be premiered at the opening of The Box, the newly remodelled and rebranded Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery. Having shot a great deal of material, the Covid pandemic stalled everything, eventually leading to a three-year delay, and a change in the film’s direction. For Akomfrah, one pandemic led to another. It is estimated that up to 95% of the inhabitants of the new world died from disease following first contact with the conquistadors. Ninety per cent of the native inhabitants of Massachusetts Bay had died in a wave of smallpox not many months before the arrival of the Mayflower, which was why the pilgrims found cleared lands and cornfields devoid of people when they arrived. Nor will you meet any of those pilgrims, lately arrived from Plymouth, in Akomfrah’s Arcadia. No corn-ears, no turkeys.

But there is always a man on the shore, his back to us, looking out to sea. And groups of people standing about and giving each other significant looks, or trudging the beach with buckets or carrying big minimalist crosses. Some wear T-shirts and trainers, finding themselves among a collection of beached grandfather clocks and a wind-up gramophone. A caption says that this is Santo Domingo 1493, but it is hard to tell. Some wander in from the costume department dressed as conquistadors in their helmets and breastplates. The tide is coming in, or going out, and the sun is either about to rise or has just dropped below the horizon. Look at this scene and you’ll miss what’s happening on the other four screens. Here come the flying fish, the frolicking seals and the dolphin sliding beneath the prow of the sailing ship as its prow cleaves the waves. Here come the toadstools and the stop-action slime-mould jerkily covering the rock. Here come Akomfrah’s tropes, familiar from earlier films by the artist. Joining the big clocks, abandoned furniture litters the beaches and wastelands. Now we are in a woodland (Yucatan Peninsula 1518, the caption reads) fly-tipped with ecclesiastical brassware and a bedstead and mattress sitting in the ferns, vestments and other bits of clothing hanging from the trees. As soon as you grab an image, another cries for attention. We go from macrocosm to microcosm, from the nature documentary to the theatrical.

With its arid vistas and undersea life, with its weather systems seen from space, the mangroves and the storm-thrashed coast, the National Geographic views of Monument Valley and the sped-up loading and unloading in the computerised container port, Arcadia is mesmerising to look at. But then Akomfrah’s work is always beautifully staged, shot, montaged and arranged. The John Dory hung from its hook, the basket of walnuts, the eye of the hurricane, the minuscule invertebrates dancing in the water column and a whale passing by: everything we see is somehow equalised. Everywhere you look, something ravishing, or quite possibly horrible, is happening. A rocky coastline is littered with skeletons and strewn with bits of clothing, and what looks to me like an inflatable crocodile. I imagine Akomfrah’s film crew carting all this stuff around with them and arranging it all on the rocks. Brief captions thrown on the screens signpost times and places where smallpox struck: Central Peru 1533, Southeast Brazil 1563, Argentine Northwest 1599, Colony of Virginia 1619, New Plymouth 1619, North Japan 1714, they say. But there really is too much going on to concentrate, especially as you are having to negotiate so much simultaneous material: the spectacular views, the meandering rivers, the mangroves and the miasmas, the plumes of sediment curdling the sea, the childish soap bubbles caught in the wind and the swarms of yellow lights flickering in the woods.

after newsletter promotion

While all this is going on, we hear snatches of Giacomo Meyerbeer’s 1865 opera L’Africaine, and listen to readings from John Milton’s 1667 Paradise Lost, read by Anton Lesser, and ancient Greek writer Artemidorus’s 2nd century AD The Interpretation of Dreams, read by David Timson. Both readings, taken from audio book recordings, add to a sense of momentous portent and gravity. The flaring auroras, the full moon, a swing and a slide on an empty beach all take on doomy significance. Towards the end the entire world heaves into view across all the screens. We fly over a big hut in a jungle, the inhabitants just visible between the trees. They might be waving goodbye. Zooming in, jungles and plains become a continuous patchwork of intensive farming and industry. The surface of the planet has the look of the inside gubbins of a computer. As the planet revolves, sprawling cities are spangled in the night, islands light up and are gone.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

If you watch a lot of HGTV (or have seen the Amy Adams rom-com “Leap Year”), chances are you’ve seen the magic that home stagers can work on a place. These experts can transform spaces and make even the most unsellable houses sell.

So naturally, they are full of great home decorating advice. HuffPost asked a number of professional home stagers for their top decor tips ― from accent walls to tabletop design ― for everyday non-experts just looking to make our spaces feel more inviting.

Here’s what they shared:

“Making your bed can be a chore, whether dwelling or selling. The key to making it feel luxurious and hotel-like is simple when using crisp white linens and plump bedding and pillows. Plump, fresh white bedding is easy to find at most major home goods stores (can be a bed in a bag or a comforter and duvet and crisp sheets) and then simply layering in two or three of the same accent pillows in front, which is easy to change seasonally.” ― Karen Otto, chief staging officer at HomeStar Staging

“In the master bedroom, create a magazine look using a comforter or duvet in a solid color or subtle pattern; put coordinated pillow shams on the bed pillows and add another decorative pillow or two for an updated look.” ― Maureen Bray, owner of Room Solutions Staging

“Splurge on a great scented candle. This isn’t where you can go cheap ― scent is everything. Done right, they make a room feel warm and inviting.” ― Joni Rentz, co-founder and design director of StylHaus

“Brighten and amplify the light in a room with mirrors on walls opposing light sources. I love mirrors because they double the visual square footage of any room. Hang a series of three or four mirrors opposite a window to reflect the incoming light as well as the view.” ― Cheryl Eisen, founder and CEO of Interior Marketing Group

“To set the right mood, add dimmers on all of your lights. Bright isn’t always right.” ― Rentz

“Lighting ― table lamps, chandeliers, etc. ― brings a lot of style into a room! Go BIG vs. smaller table lamps!” ―Kathy Burke, founder of Sensational Home Staging

“Replace dated light fixtures in the main rooms of your home to make it feel more inviting; use high-wattage bulbs in lamps and light fixtures for maximum effect.” ― Bray

“Layer and mix textures to create visual interest. For instance, add textured pillows and a fur throw to create an inviting sofa.” ― Rentz

“Bigger is better when it comes to art. Large canvases add a statement to any room and can even make wall space appear larger.” ― Eisen

“Paint an accent wall. It not only adds a focal point to a room but can function as a great backdrop for artwork.” ― Rentz

“Wondering where’s the best place to hang art or other wall decor? Center it above whatever furniture is below it (sofa, sideboard, fireplace mantle, dresser, or console table) and make sure that the midpoint of the art is about 60 inches from the floor.” ― Bray

“Create the illusion of higher ceilings with simple floor-ceiling drapes. Plain, white sheers can go a long way on a budget, but make sure they’re hung properly. Drapes should start all the way at the ceiling and just kiss the floor.” ― Eisen

“Add beautifully folded fluffy white towels, eucalyptus, a chunky bar of soap and a few, well chosen, decorative items to create a spa atmosphere.” ― Rentz

“Find a unique piece of furniture and make it a ‘corner quirk moment.’ For example, a Danish, mid-century wood chair with a fur pelt draped over it adds a level of authenticity to a design. You don’t want your space to look like a ‘set’ or a furniture showroom.” ― Eisen

“De-clutter and de-stress. Too many items on coffee tables, pillows on chairs and art pieces on walls make a space feel cramped. Stick to a few statement pieces and oversize art to give your room a clean, modern look.” ― Eisen

“Less is always more! In other words, showcase your personality and style through thoughtfully placed accessories and art, and avoid unnecessary clutter.” ― Florence Attinger, head of the San Francisco staging and design team at Studio D

“To add new life to your seating areas, use some new throw pillows in colors that complement the art or wall decor on nearby walls.” ― Bray

“Trying to get a pop of color in your space and it never feels quite right? Try using one color accent three times in the room! The eye naturally travels in a space and when you carry a color through the room, whether it be in the rug, art, pillows or décor accents, it almost always works and feels right.” ― Otto

“If a room just doesn’t ‘feel’ right, it probably isn’t. We often push furniture against walls to create what we feel is a more spacious environment, but it really ends up feeling like a waiting room and not very conducive for conversations. Instead of wall hugging, try floating your furniture.

Find a central point in the room (often around the fireplace, under a ceiling fan, or if you must, around the TV area). If you have solid surface floors like wood or tile, I would recommend getting an area rug no less than 6’x9’ in size. The right scale area rug will ground the space and the furniture. Anchor a coffee table in the center point of the rug and gather your furniture around it leaving at least 18 inches between the soft furniture and the coffee table. You may have to choose a larger piece of furniture to anchor the coffee table on if your furnishings don’t all work at that distance. It is perfectly acceptable to place the front feet of the soft furniture on the rug and the back feet off!” ― Otto

“A fresh coat of paint is inexpensive (and DIY-friendly), but the effect can be HUGE in the way a space looks and feels.” ― Attinger

“Walls that are freshly painted in a neutral color will show off your furniture and wall decor to their best advantage (and also make the house feel well-maintained). Painting the wood trim around baseboards, doors and windows also makes the space more appealing, especially when using white paint to contrast with the wall color.” ― Bray

“Go with neutrals for those large pieces ― sofas, beds, rugs, lamps, etc. You can add color/interest/drama with your art and accessories. ... Clients spend a fortune on a bright-colored or highly stylized sofa that they are tired of in three years. When you’re tired of the ‘look’ you have but not over-invested, you can, on a budget, redo your look again with art and accessories. Choose a new color or a new style. It’s easy, fun and not expensive!” ― Burke

“Strategically using dark paint and dark pieces will not only add depth to a space, but also create mood and drama.” ― Eisen

“Custom furniture can be easy. Add your own handles, paint and even different legs to ordinary pieces to make custom items at an affordable price.” ― Eisen

“Odd numbers rule for designing to dwell, or staging to sell. For tablescapes, keep it simple if you don’t want too much stuff out, and remember the numbers one and three. You can use one good scale piece or three of the exact same type decor pieces (think succulents in pretty planters, hurricanes [candle holders] or a large metallic bowl). These are easy, affordable centerpieces, whether it’s for your dining room or coffee table, and these can be changed seasonally too.” ― Otto

“When creating a centerpiece for your tables, start with a tray and select three objects of varying heights: a hardcover book or two, a plant, and an interesting object work well together. Large coffee-table books also work well when two or three of them are stacked on a coffee table.” ― Bray

“Swap out heavy, dark, or dated window coverings with simple panels that let more light into your rooms; the space will feel larger and more appealing.” ― Bray

“Not everything needs to be bought brand new or have a designer label on it. In fact, good design is all about balance; and sourcing from all different places and price points will keep your space feeling authentic and inviting.” ― Attinger

“I think the most important advice one can give for everyday people is follow the experts ― the fabulous home decor publications such as Elle Decor, World of Interiors, Architectural Digest, etc. ― so you get a feel for what is wonderful design from a variety of different styles. Everyone has their own look or vibe. Find a designer you like, and see what their approach is.” ― Nahila Chianale, owner and head designer at NCC Luxe

“I think there is a lot to learn from the internet. Use it as a tool to help you learn. But never buy things online as a non-professional ― 99.9 percent of the time, you will be disappointed or the proportions are wrong. Go into the showrooms and ask for help.” ― Chianale

Responses have been lightly edited for clarity and style.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

For the past several weeks, dozens of candidates have been facing a five-person committee in a dark, book-lined room at Italy’s Culture Ministry, hoping to convince the panel that they should be selected to direct some of Italy’s top museums, including the Uffizi in Florence, the Capodimonte in Naples, the Brera in Milan and seven others.

Ten candidates are up for each job. The committee will whittle each list down to three, based on the interview and the candidates’ knowledge of a host of issues — new technologies, cultural heritage legislation, sponsorship opportunities — as well as their vision for each museum. The final selection will be made sometime next month by Gennaro Sangiuliano, Italy’s culture minister, and Massimo Osanna, the ministry’s director overseeing museums.

It has been eight years since a reform granted some Italian arts institutions greater autonomy and opened up the position of museum director to people from outside the culture ministry’s ranks. The then-culture minister, Dario Franceschini, sought applications from foreigners to shake up the museum sector, even publishing the job advertisement in The Economist magazine. At the first 20 museums affected by the reform, Franceschini appointed seven foreigners and several Italians with experience abroad, who were hired for a four-year contract, that could be renewed once.

“It was an opening that brought fresh air into the whole system,” said Luca Giuliani, an archaeologist who was part of the 2015 committee that selected those directors. However, many Italian art historians and archaeologists had felt snubbed, and several colleagues stopped speaking to him, he said.

This time around, the mood is different. Though the new minister, who is part of a nationalist, right-wing government, has said that nationality was not an issue, of the 90-odd candidates shortlisted (some are in the running for more than one museum), only a handful have significant experience outside Italy. And two of the foreigners up for jobs already run two top Italian museums.

Given the government’s political bent, “it would have been a surprise if they had been looking for international candidates,” Giuliani said.

In an email, Sangiuliano said that there were “no preclusions on nationality.” What mattered, he added, was that a “director had to be good and have ideas.”

Yet culture experts say that the prestige and perks of running an Italian museum — which include some of the world’s most celebrated arts institutions — are dampened by downsides including lower salaries compared to comparably important museums abroad, limited contracts and the many headaches of Italian bureaucracy.

“I think that a colleague that has worked in the United States, or in England and Germany, might wonder whether it’s worth it,” said Enrico Parlato, the president of CUNSTA, an Italian association of university art historians. “To be crude about it, the salaries cannot compete,” he added.

Critics also say that by giving the culture minister the last word over the choice of directors, the 2015 reform also gave the minister outsized influence, including over diplomatic questions like loaning rare works abroad, or dictating the content of exhibitions.

“The reform was intended to put museum directors on a leash,” said Tomaso Montanari, the rector of the University for Foreigners of Siena and a well-known cultural critic. He cited the National Modern and Contemporary Art Gallery, which recently opened an exhibition on J.R.R. Tolkien, the author whom Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni has cited as an inspiration. “There is very strong political intrusiveness,” Montanari added.

Under the Franceschini reform, 20 of Italy’s top museums — including the Borghese Gallery in Rome, the Accademia in Venice and the Archaeological Museum in Naples — were given more managerial autonomy, shifting oversight for budgets from the culture ministry to the directors, who were also encouraged to fund-raise.

But the reform had an impact beyond that top tier. Museum revenues that were once given to the culture ministry and redistributed among less visited sites now mostly remain in the coffers of the autonomous museums.

Sixty museums now have some level of budgetary and administrative autonomy. Montanari said that financial independence had forced those museums to try and attract as many visitors as possible, “using a business logic,” which he said was the antithesis of their cultural mandate.

But some of the museum directors whose terms are expiring said that, without the reform, many of the changes they enacted during the past eight years would never have happened. Under the old system, requests to make major changes had to go through long pipelines before they were approved, as did requests for funding.

At the Capodimonte Museum in Naples, the French art historian Sylvain Bellenger restored and revitalized the surrounding 330-acre park, transforming it from a neglected haunt of drug dealers to a pristinely landscaped, much frequented park.

The revamp was only possible “because of the reform, when for the first time Italian museums looked toward international standards and realized they were much behind,” said Bellenger, who has become so popular in Naples that thousands have signed an online petition begging Italy’s culture minister to extend the contract of “the man who changed the face of Capodimonte and of our world.”

Eike Schmidt, the German-born director of the Uffizi Galleries, said the reform had required directors to become “visionary,” and that financial independence demanded finding ulterior sources of revenue through sponsors and donors.

Schmidt has made the shortlist to lead the Capodimonte Museum, but might also make a run for mayor of Florence in elections next year, an eventuality that “under certain conditions I would not exclude,” he said in a recent interview.

Some directors said that the 2015 reform fell short on a number of fronts, however, especially when it came to hiring staff, which still depended on an open competitive exam through the culture ministry. That meant that they couldn’t hire who they wanted. And Italian bureaucracy also dampened efforts for massive change.

James Bradburne, the Canadian-born, British director of the Brera Museum, said he’d struggled to overcome some of the museum’s “profoundly flawed” structures, like the way human resources were allocated, or administrative loopholes that slowed down getting economic resources. These created “multiple moments for delay, change, error and waste,” he said.

“When I raise this point, which I’ve raised for eight years, they look at me and laugh and say, ‘Oh James, siamo in Italia,’” — we are in Italy — “the universal answer for things that are patently absurd and a waste of money and don’t make sense,” he said.

The culture ministry declined to say how many foreigners had applied for the jobs this time, yet Montanari said that the lack of foreign candidates on the shortlists suggested that, at the very least, top officials from comparably prestigious museums had not applied.

“You have a country like Italy, which has all the problems, without all the financial means,” Montanari said, “even as you have politicians breathing down your neck. “

“It’s no wonder that directors of foreign museums didn’t apply,” he added. “They’re not stupid.”

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

Hidden among the postcard mountains outside Beijing, this Youli Bed & Breakfast takes shape with architecture by Beijing-based studio Brick & Cube Architects. The vision of a middle-aged couple seeking to escape the city, this boutique hotel is a blend of natural beauty and thoughtful design. Inspired by the Japanese documentary ‘Fruit of Life,’ which explores the essence of daily life through meals and seasons, the architects engaged in a dialogue with the owners to bring their pastoral vision to life. Despite not physically being on-site initially, the team envisioned a design that would respond to the surrounding landscape.

images courtesy Brick & Cube Architects

Upon arriving at the site of its Youli Bed & Breakfast, the team at Brick & Cube Architects was inspired by the mountainous terrain, although the existing structures on-site brought challenges. The original houses were typical rural self-built structures. The critical task became finding a balance — how to connect with the natural environment, enhance interior and outdoor spaces, and cultivate a comfortable pastoral atmosphere. To address limited interior space and harsh winter conditions, the architects incorporated the original courtyard into the building. The eastern gable of the main house boasts a distinctive slanted roof, offering visual impact and echoing the mountainous backdrop. The design strategically plays with geometry, using triangles and rectangles to create an harmonious composition.

Brick & Cube Architects transforms two small houses into a warm, pastoral retreat outside Beijing

Beyond the aesthetics of its Youli Bed & Breakfast, Brick & Cube Architects aimed to establish a dialogue with traditional Chinese architecture. The design draws inspiration from the classical three-stage composition found in ancient structures, addressing functional needs while paying homage to cultural heritage. The entrance, originally facing the street, was reoriented vertically, creating a triangular and rectangular entrance space. This not only serves a practical function but also guides visitors through an experiential journey, blurring the boundaries between indoor and outdoor spaces.

surrounded by mountains and cloaked in shadow, the B&B glows like a beacon

the eastern gable features a slanted roof which harmonizes with the sloping landscape

the entrance, once facing the street, is vertically reoriented, creating a unique triangular and rectangular entrance

the architects incorporate the original courtyard into the building, addressing the need for more interior space

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

The team drew inspiration from Czech writer and critic Karel Teige’s influential book on architecture, “Minimum Dwelling”. One of the most important figures of avant-garde modernism during the 1920s and 1930s, Teige wrote the book as a blueprint for a new way of living, exploring the role of modern architecture in planning, design, and construction new dwelling types for the working class. In it, he defined the ‘minimum dwelling’ as a form of domestic space organised around two poles, the individual cell and communal facilities. For Atelier tao+c, the property’s vibrant neighbourhood takes on the role of the latter, allowing the apartment to be designed as a monastic cell.

Leaving the small kitchenette and bathroom intact, the team radically reconfigured the rest of the apartment into a fluid space where the sitting, dining and sleeping zones flow into one another. A key part of the new layout is the custom-designed shelving system that incorporates most of the apartment’s furnishings, from bookshelves, cabinets and desks, to a raised platform built specifically for the bed. Painted in a deep green hue, the muti-functional structure both demarcates and unifies the independent yet interconnected living zones.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

The rocking chair’s appeal can be attributed to something beyond the physical motion inherent to its form, for the rocking chair is a piece of furniture inviting unhurried contemplation and relaxed playfulness only matched by its swinging cousin, the hammock. There you are, perpetually moving, but never really getting anywhere. But that’s all part of its charm. The Penguin Rocking Chair is a classic representation of that intermediary state between sitting and moving, our personal favorite rocking chair, all done with a visual lightness that looks every bit contemporary today as when it was first revealed in 1953.

Like many things said and done, the rocking chair as we know it is often attributed as an invention of American polymath, Benjamin Franklin. But according to Witold Rybczynski, author of Now Sit Me Down, a comprehensive history of the chair, this is not correct. A bill for a “Nurse Chair with rockers” crafted by Pennsylvania cabinetmaker Solomon Fussell in 1742 was the first formal mention of a rocking chair in writing. Timelines tracking the first mention of rocking chairs also reveal a 6-legged predecessor common to Sweden called the “gungstol” (now readily available today in spirit as IKEA’s POÄNG rocker, sans those 6 legs).

The mid-century years are not typically the era most associated with the rocking chair. Yet, lo and behold, there was Ray and Charles Eames in 1950 with their playful fiberglass single-shell RAR armchair, and George Nakashima’s single-armed 1960’s design. Before that, Hans Wegner’s Shaker and Windsor inspired rocking chair had the Danish relaxing all the way back in 1944.

And so too, iconic Danish furniture designer Ib Kofod-Larsen imagined his own rocking chair, the Penguin, in 1953. It was one in a series of seats, a variant of a more traditionally legged dining chair of the same name. And now furniture brand Audo has revitalized the design with a few modern touches.

Kofod-Larsen’s original design for Christensen & Larsen featured wrought iron framework, a cushioned upholstered seat, and an angled molded birch back that gave the chair’s profile a sort of mid-century silhouette on skis vibe. The design abides by Kofod-Larsen’s Danish Modern dictum: “Design furniture for everyday use, not to impress people.” You can still occasionally find originals in varying degrees of condition online and in vintage shops.

Each chair is made to order, with 7 standard upholstery colors available for the fully upholstered edition or 9 standard upholstery colors for the wood back rocking chair model (alongside the choice between natural oak or walnut for the seat’s back).

Audo’s revived Penguin Rocking Chair maintains the original’s sculptural open design, offered as an all-wood curved back and seat chair, one with wood, leather, or fabric upholstered seat and back, or a combination of both, with all versions supported by a steel frame. Today the Penguin Rocking Chair’s cut steel frame is welded by robotic welding and then powder coated; the seat and back are each made from bent plywood with the rockers CNC carved from ash before being painting.

What’s particularly exciting for enthusiasts of Kofod-Larsen’s timeless design is now you can get his rocking chair with an all-wood seat and back, or with Kvadrat wool worsted upholstery, boucle, or leather in a dizzying range of colors and textures (custom upholstery available through Audo’s upholstery program at an extra cost). The color options open up the Penguin Rocking Chair to take on a contemporary presence transcending its vintage origins, likely to surprise the uninitiated that people were rocking out in style 70 years ago in such modernist fashion.

The Penguin Rocking Chair is available starting at $1,165 with the fully upholstered edition priced starting at $1,880, both at us.audocph.com.

This post contains affiliate links, so if you make a purchase from an affiliate link, we earn a commission. Thanks for supporting Design Milk!

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

Sometimes, early in their career an artist makes a body of work so powerful and singular, and so necessary, that it comes to define them, and critics end up measuring the rest of their work in its light. So it is with 68-year-old American artist Pope.L, whose belated first UK show now fills South London Gallery (SLG). In 1978, Pope.L crawled the length of New York’s 42nd street on his hands and knees, carrying a small potted flower as a sort of prop. He wore a thrift-store suit with a yellow square stuck to his back. Later, he went on to crawl from one end of Broadway to the other. He crawled around Tompkins Square Park and he crawled in Miami. These grim, high-endurance public performances made his name and bought with them a degree of both fame and notoriety.

Talking at the SLG this week, the artist said that a lot of people talk about “care” and “precarity” in the art world, but that as supportive as the art world can be, it is really all about power and money. He recalled that in the 1970s whatever support there had been for homeless people, and for physically and mentally ill New Yorkers, was withdrawn (in a brutal American version of “care in the community”), and that many, including the artist’s own father, aunt and brother, ended up surviving in dire circumstances on the streets.

In his many versions of Crawl, the artist put himself in danger. He could get run over as he crossed the street or attacked on the sidewalk. He risked assault and arrest, to say nothing of the physical and psychological demands this simple act made on him. He learned always to have people with him, even if at a distance. There was something gruelling, extreme, stupid and brave about Crawl, the artist adopting the position of the penitent or the religious fanatic, the most base and abject of those at the bottom. Crawl was something more than, perhaps other than, a performance.

A wreck is marooned on the floor of the main space at SLG. A ghost ship, a Mary Celeste, with no one on board. Instead of a crow’s nest a wrecked porcelain toilet bowl lunges from its plumbing into empty air. Another toilet, up on a now slumping, rickety tower, is clogged with newspaper. A number of fishing rods baited with yet more newspaper dangle uselessly over the side. The whole thing occupies the length of the gallery and it has run aground before hitting the red plastic butcher’s curtain at the entrance. The timber wreckage is snowed with thick white dust, as if it has come through a blizzard or had a run-in with a drug lab up the coast. The only signs of life are the milk cartons strewn over the deck. The white dust piles up on the superstructure and you can sprinkle some more yourself from the little bowls provided. “Dust, sprinkle at will,” signs say, helpfully. In one throwaway line Pope.L has remarked, “You always want a bit of whiteness around”.

The only thing missing here is the artist himself. The wreck in the room is a set for a performance that isn’t going to happen. In earlier versions of this work the artist has sat on one of those toilets up a tower, wearing nothing but a jockstrap, covered in flour and reading and eating his way through pages of the Wall Street Journal, lubricating the newsprint with milk as he forces it down. The performance was inspired by a WSJ advertising campaign at the turn of the century which implied that you don’t have to read the paper to benefit from it: buying it was enough. Like a talisman, just touching it provided you with knowledge, so consuming it might provide untold power and wealth. Pope.L sat on the can and ate the paper in a sort of parodic ritual. “It was yummy,” he lied.

High up on the gallery walls, speakers broadcast the sounds of dust sifting and falling and timbers collapsing and there’s a slow drip of liquids from various tipped-over bottles of cheap hooch arrayed on shelves, the drips catching in saucers and spattering on the floor. Some leaks down the walls, staining the new pale pink paintwork. Some of the liquid looks and smells like booze and sometimes you worry its blood or lymph or some other unnameable bodily secretion. Booze is a cheap way to self-medicate. For the artist all these bottles are also a nod to the rituals of Catholicism: “Catholics are into liquids and rituals”, he has remarked. A thin reek of ethanol pervades the gallery. It reminded me of the stink of a bar at 10am, and the solvent smell of disinfected hospital wards.

The title of Pope.L’s show is Hospital. Banners hung outside display pale pink versions of the familiar Red Cross symbol. But don’t expect much care or succour here. In the Old Fire Station across the road, two rooms elaborate the works with bottles and liquids. The best is the emptiest. A long shelf runs across the windows. On it sits a plastic drinking straw running through the lid of a cup (the sort patients who can’t raise a glass to their lips use). The cup has fallen to the floor and is dramatically spotlit. A stripped-down scene of an everyday incident, it left me teetering.

after newsletter promotion

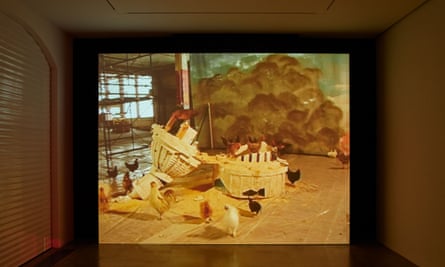

The best thing here is Small Cup, beautifully filmed in an abandoned textile mill in Lewiston, Maine, in 2008. It is winter and sleet is falling. In the mill itself the artist has made a ramshackle scale model of the Capitol building in Washington. Chickens flap about and peck at the model, which has been covered in seeds. Goats trample over the toppled cupola, searching for food. The film flips between these animated scenes and views of the cavernous, empty mill, the harsh New England winter and the river flowing by, industry long gone. Funny and bleak and atmospheric, it is difficult not to equate the film with the insurrections in the Capitol on 6 January 2021 by supporters of Donald Trump. The film might almost be a premonition. A cup falls. The Capitol falls. Gravity has its way. People end up on their knees. Talk about precarity.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

Temporary wallpaper lets you try out new trends and styles in your home without the commitment off permanent wallpaper.

Whether you’re in an apartment, dorm, transitioning a room from office to nursery, or just don’t want to commit to an entirely new paint job, removable wallpaper is the perfect upgrade without breaking the bank.

HuffPost may receive a share from purchases made via links on this page.

See below for some of the best places to buy removable wallpaper:

Looking for the best deal before you buy? Take a look at HuffPost Coupons where we have hundreds of promo codes from brands you trust.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

There’s more than one answer to the question “What is photography?,” and this fall in London, there are a dazzling array of possibilities on show in retrospectives of the Japanese artists Hiroshi Sugimoto and Daido Moriyama.

Born 10 years apart (Moriyama in 1938, in Osaka, and Sugimoto in 1948, in Tokyo), both photographers came of age in Japan’s postwar photography boom. During this time of political change and technological innovation, practitioners explored, and frequently critiqued, the photograph as journalistic document, art object and mass media advertisement. Photo books and photography magazines proliferated, as did connections with American art scenes including Minimalism, Pop and the grainy realism of street photography.

Both photographers are also invested in the more ephemeral, even metaphysical, qualities of the medium: How it freezes or reconstitutes time, brings the dead or the inanimate to life, unsettles concepts of memory, reality and vision itself. If these questions unite Moriyama (whose London show runs at the Hayward Gallery, through Jan. 7, 2024) and Sugimoto (at the Photographers’ Gallery, through Feb. 27) their many-decade oeuvres could scarcely be more different.

“All my life I have made a habit of never believing my eyes,” Sugimoto has said. Across four floors of the Hayward’s stark, Brutalist galleries, nine black-and-white series spanning 1976-2022 are staged in austere displays. Each body of work addresses the seen and the unseen, exterior and interior life, with deceptive simplicity.

A sequence of “Diorama” photographs, begun shortly after Sugimoto arrived in New York in 1974, capture scenes from the American Museum of Natural History with otherworldly precision. Using an old, large-format camera, long exposure times and elaborately tuned lighting, Sugimoto enhanced both the artifice and the verisimilitude of the institution’s taxidermy wildlife tableaus behind glass.

“Polar Bear” (1976) shows the majestic white animal roaring over a fresh kill: the bloodied body of a seal whose inert form is bulky and dark against an Arctic white background that stretches into the distance. Look closely and behind the bear — with its luscious coat of fur, its big paws so heavy in the snow you can almost hear it crunch — the line between two and three dimensions is just visible: a jagged crevasse in the ice floe beneath the two animals merges almost seamlessly with a painted backdrop of receding icy peaks.

The eye judders between these realities. The dead bear, momentarily brought to life by the vividness of the photograph, dies again, and is preserved again, a copy of a copy, frozen between past and present. Similar fates await a pair of ostriches defending their new hatchlings against a family of wart hogs (“Ostrich-Wart Hog,” 1980) and a placidly floating mother manatee and her calf (“Manatee,” 1994).

Sugimoto’s play with photographic abstraction is evident in a series of “Seascapes,” dominated by long horizons and blank skies, “Lighting Fields” produced with bolts of electricity sent across sheets of unexposed film and rich chromatic studies (“Opticks”) made by shining light through a prism demonstrate Sugimoto’s play with abstraction. But it’s the “Theaters” series, arguably his most famous, that maintains the most beguiling promise of photography to capture a flickering in-between state.

In cinemas, drive-ins and abandoned palace-style theaters across the United States (and sometimes Europe), Sugimoto set his camera’s exposure time to the length of a movie screening. His device sees what no naked human eye can apprehend: a bright white vortex of time elapsed, frame upon frame upon frame, at once stilled and in motion. In Massachusetts, Indiana, New York, Philadelphia, the shadowy rows of seats, crumpled velvet curtains and decorative wall moldings are irradiated by a central focus that is not an image but a light so bright and uncontainable that its edges are smudged like a ghost.

Across town at the Photographer’s Gallery, also unfolding across four floors, the Moriyama retrospective does away with any sense of the photograph as a rarefied art object. Where Sugimoto’s images are clear, large, refined, singular and precious, Moriyama’s are multiple, democratic, immersive, rapid and haphazard, and varied in size, material and presentation.

“When people realize that the time they supposedly live through actually has no substance,” Moriyama has said, “they tend to be seized with fear and an unspeakable apprehension about the excessive uncertainty of it all.” In the end, he added, “human existence has essentially nothing to rely on.” Displayed on wallpaper, in grids, projections, photocopies, conceptual assemblages, contact sheets and books, his work embraces the dark flux of life that cannot be contained, but must somehow be preserved.

Moriyama’s subjects are accidents, political conflict, urban ennui, loneliness, cheap commercial goods, all the details of the everyday — as many as possible — caught in passing and printed in high-contrast black-and-white. Rakish angles, extreme close-ups, blurred fragments and decentered, deliberately awkward cropping dominate the profusion of images arranged in nonlinear displays that leave interpretation to the viewer: an open mouth, a movie theater marquee, a boy playing with a ball, Lyndon B. Johnson on a television screen, a crowd of police in the night, a black cat in a hallway.

In his 1969 “Accident” series, chaotic combinations scramble perspective while also taking aim at the omnipresence of mainstream media sensationalism. Later series are more intimate and melancholy. “Farewell Photography” (1972) brings together images that might usually be considered errors — grainy, blurry, out-of-focus (are, bure, boke in Japanese) — to dismantle photographic expectations of clarity and truth.

In “Memories of a Dog” (1982), made during a period of creative crisis, Moriyama revisits locations of his peripatetic childhood in search of scenes that reflected his current interior state: scrolls of film, a hand against the sky, a cherry tree in blossom — as if photography were a form of time-travel, bridging the rift between past and present.

What world does a photograph show? Is it a record or a work of art? As Moriyama wondered, “What is the work that unites light, time and the visible world?” In these two exhibitions, which encourage slow, careful, sometimes rapturous looking, there is — refreshingly — no need for an answer.

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

Artemest, the online platform showcasing contemporary Italian design, unveils its reimagined gallery space, Artemest Galleria, in West Chelsea, Manhattan. Designed and curated by Italian architect and interior decorator Samuele Brianza, the revitalized space revolves around the question ‘What makes Italian design so special?’. The answer comes in the form of a thoughtfully curated exhibition featuring furniture, lighting, and objects crafted from traditional materials using techniques representing various regions of Italy.

the interior of the revitalized Artemest Galleria in West Chelsea | all images by William Jess Laird

The redesign of the Artemest Galleria (find more here) was carried out by Samuele Brianza (find more here) in collaboration with the platform’s founder and creative director, Ippolita Rostagno. The gallery offers visitors the opportunity to view an elegant interior consisting of various pieces of furniture, and decorative objects created by over 50 Italian designers.

Inspired by Milanese interiors, the room is decorated with fabrics by Rubelli and Bevilacqua. Polished Veneziano stucco surfaces are framed by waxed oak and contrasted with warm lime surfaces reminiscent of Milanese villas. In the main area, a custom walnut counter carved by master craftsman Giuseppe Rvadossi is used to display decorative pieces. Throughout the gallery, earthy tones recall the hills of Tuscany, while inviting armchairs and sofas are gently placed between intricate room dividers. Above, chandeliers with floral motifs draw the eye and illuminate a selection of objects made from Murano glass, terracotta, hand-painted ceramics and silver.

‘Working between Milan and my home base of Manhattan gives me a unique and very global perspective on what Italian design means and how we can communicate this ethos in just one exhibition,’ shares Brianza. ‘I focused on the core values intrinsic to Italian beauty in design, I considered the elements of tactile and visual nuances, striking the delicate balance between form, function, irony and memory’.

the space revolves around the question ‘what makes Italian design so special?’

polished Veneziano stucco surfaces are framed by waxed oak and contrasted with warm lime surfaces

the gallery showcases furniture and decorative objects created by over 50 Italian designers

chandeliers with floral motifs illuminate a selection of objects made from Murano glass, terracotta, and silver

[ad_2]

Source link

[ad_1]

An emblematic example of Belle Epoque architecture on the Basque coast, the Regina Hotel & Spa, as the property was originally named, was built in 1907 by architect and landscape designer Henry Martinet in the Neo-Basque style with plenty of Art Deco touches animating the interiors, most impressively in the monumental 15-metre-high atrium. Topped with a glass roof designed in the style of the Eiffel Tower, the grand, light-filled space is where the hotel’s heart beats, now serving as a foyer and bar.

Thoughtfully configured by Meilichzon into numerous intimate sitting areas, the expansive space is populated with voluptuous sofas inspired by the Itsasoan footbridge that architect Henri Godbarge built in the 1920s in Guéthary, a charming village a few kilometres away. The sofas are swathed in brick-red, dark green and Prussian blue hues, a nod to the typical colour palette of the Neo-Basque architecture style. Low-hanging paper lanterns by Ingo Maurer and Anthony Dickens, and straw totems provide a more human sense of scale, while natural materials like sandstone, ceramics, and natural fibres complement the space’s Art Deco glamour with a vernacular charm. Serving a selection of classics and signature Experimental cocktails accompanied by live piano music and DJ sets, the long bar counter at the back of the space pays homage to modernist architect Eileen Gray.

[ad_2]

Source link