Category: Design

Prism review – three-part film essay turns the camera on race, colour and imperialism | Movies

[ad_1]

A collaborative project between film-makers Rosine Mbakam, An van Dienderen and Eléonore Yaméogo, Prism interrogates the supposed neutrality of the photographic lens, principally in regards to representations of race. Moving through the corridors of a film school before alighting on a sparse set where a lighting test is taking place, Dienderen’s section unfolds as a continuation of her short film Lili, which grapples with a cinema practice called “china girl”. Used for calibration purposes, these test images usually feature a white model and a colour chart; in other words, colour films were made with only white skin in mind.

While Dienderen’s work grapples with camera bias on a technical level, Mbakam and Yaméogo expand the argument by pointing to larger ideological frameworks. In her segment, Mbakam draws an explicit link between imperialism and cinema; early footage of Africans, for instance, was taken by their colonisers. And restaging Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s famous painting Portrait of a Black Woman with a live model, who applies her own makeup and stares back at the viewers with defiance, Mbakam reclaims the autonomy of marginalised figures from the white gaze.

Structured around candid interviews with Black talents such as the actor Tella Kpomahou and director Sylvestre Amoussou, Yaméogo’s contribution argues that the camera’s racial bias is not set in stone. While systemic hurdles remain, works by visionary film-makers ranging from Senegalese pioneer Paulin Soumanou Vieyra to Spike Lee have shown that Black lives can exist on screen in their full vibrancy and complexity. In creating a dialogue between the three different segments, this prismatic exploration of race and cinema emphasises how film-making can never be a monologue, but a conversation.

[ad_2]

Source link

How to Choose and Hang Wallpaper

[ad_1]

Wallpaper is a powerful design tool that can transform a room.

You start with a white box and end up with what feels like an entirely different space, wrapped in an intricate floral design or a bold geometric pattern.

But which one: Intricate or bold? Floral or geometric? With so many colors and patterns available, choosing one can feel almost impossible. And once you do, how do you avoid botching up the installation?

Todd Nickey and Amy Kehoe, of the Los Angeles-based design firm Nickey Kehoe, often wrap rooms in color and pattern, so we asked them for advice. And Mr. Nickey, who happened to be wallpapering his own bathroom, invited us along to see how it’s done.

Where Should the Wallpaper Go?

The first step is figuring out where you’re going to hang the wallpaper. Keep in mind: Not all rooms are good candidates for wallpapering.

Smaller, darker spaces like bedrooms, dens, offices and bathrooms — where “you want to feel like you’re enveloped,” Ms. Kehoe said — are the best places to hang wallpaper. Larger rooms with great light and beautiful views are often better left alone.

Once you’ve settled on a room, your decisions aren’t over. Where exactly in that room should you hang the paper?

A typical installation involves covering all four walls. But that’s not the only option.

If Mr. Nickey and Ms. Kehoe are working with a lively pattern in a bedroom, for instance, wallpapering a single wall behind the bed may be enough. Sometimes a visual surprise that doesn’t overwhelm the room is all you need.

Using too much loud wallpaper throughout your home? Mr. Nickey has a term for that. “Abuse of wallpaper,” he said, “is a design mistake.”

A better option, he added, is to “punctuate a house with these moments of something really dynamic, and let other things fade to the background.”

In his own bathroom, Mr. Nickey limited himself to papering the top part of the wall, above the tiled wainscoting.

Another option: Wallpapering the ceiling instead of the walls.

Measure and Plan the Installation

Measure the walls or ceiling you plan to cover and consider how the width of the roll you’ve chosen will work in the space.

Small-scale patterns provide flexibility, but if you have a large-scale pattern, try to make sure the center of that pattern is right where you want it.

“It’s nice if it can line up with the entrance, so you’re looking at the feature of the wallpaper in a doorway,” Mr. Nickey said.

Similarly, try to avoid placing the roll in such a way that you end up having to use thin scraps of wallpaper in the corners of the room.

Once you know where you’re putting the wallpaper, calculate the number of rolls you’ll need to cover the width of each wall. And make sure to include extra length — known as “overage” — for each strip, so the pattern can be lined up and trimmed as needed during installation.

Then add an additional roll to your order.

“We always order one extra roll, because you never know when something is going to be damaged,” Mr. Nickey said. Because printing colors can vary from lot to lot, he noted, you may find it difficult to locate a perfect match later.

Prepare the Wall

Wallpaper isn’t a fix for damaged or uneven walls.

If your wall has lumps and bumps, holes or a thick texture, those problems will be visible on the surface of the paper if you don’t correct them before installation. Popped nailheads should be hammered flat, holes should be filled and textural treatments should be covered with a smooth skim coat of plaster, Ms. Kehoe said.

If your wall has many minor imperfections, she added, you may want to use lining paper — blank wallpaper that is installed before the patterned paper, to help smooth things out.

Paste It Up

With all the decisions made, it’s time to paste the wallpaper up with adhesive. Mr. Nickey and Ms. Kehoe usually hire a professional installer, but you can hang the wallpaper yourself if you take the time to keep the paper straight and the seams aligned, while trimming it to fit around corners, doors and windows.

Once the wallpaper is hung, don’t be afraid to hang decorative accessories like pictures and drapery. It’s natural to feel nervous about hammering nails or drilling holes into the paper you’ve so carefully installed, but if you want a finished room, there’s no other option.

Take a deep breath, think twice about where you want art and accessories, and proceed.

“Know thyself,” Ms. Kehoe said.

“And wallpaper accordingly,” Mr. Nickey added.

For weekly email updates on residential real estate news, sign up here.

[ad_2]

Source link

new inflatable fliteboard with electric hydrofoil makes splashy debut at miami boat show

[ad_1]

New inflatable fliteboard with electric hydrofoil

Fliteboard unveiled its new foam-based inflatable plank with an electric hydrofoil during the Miami International Boat Show. In the event, running from February 14th until the 18th, Fliteboard’s new Flite Air range made a splashy entrance as the revamped carbon fiber base is now offered with an inflatable sibling, still equipped with the electric hydrofoil that makes the board surf, fly and glide above and on the water.

images courtesy of Fliteboard

fliteboard range at Miami International Boat Show

The Flite AIR range, revealed during the Miami International Boat Show, from Fliteboard offers the same electric hydrofoil technology developed by the brand but differs since the Flite AIR and AIR PRO come with a patent-pending rigid inflatable board. Fliteboard has been developing this inflatable technology since 2018. They pulled it off by combining a solid riding platform with an inflatable drop-stitch outer bladder.

Fliteboard unveiled its new foam-based inflatable plank series with an electric hydrofoil

The drop-stitch technique allows for the top and bottom layers of the inflatable board to be connected, preventing them from popping outwards or being removed from their casing when Fliteboard AIR and AIR PRO are inflated. Because of the breeze pumped inside the inflatable base, the new Fliteboard is easier to transport, lighter, and more responsive, all the while helping the brand reduce their production costs and improve their board’s durability.

during the Miami International Boat Show, Fliteboard’s new Flite Air range made a splashy entrance

Two models in the new inflatable fliteboard range

The inflatable core and technology may be the reason why the new Fliteboard with an electric hydrofoil can easily jump above water and descend back on it without being tipped over. The recent range comprises two different-sized inflatable boards. Flite AIR is 5.8 inches long, making it ideal for everyone, from beginners and intermediates to advanced riders. For those who are up for some challenges, the more agile Flite AIR PRO stands at 5.2 inches long, similar to the original carbon fiber-bodied Fliteboard PRO.

the Flite AIR and AIR PRO come with a patent-pending rigid inflatable board as their base

Both models of the inflatable Fliteboard with an electric hydrofoil are available in three vibrant colors named Yuzu, Pompelmo, and Açai, all reflecting beachside locations. David Trewern, the Fliteboard Founder, CEO, and Product Architect, comments that ‘Flite AIR is great for using on and off boats, docks, rocky beaches, or for school and rental applications. Compatible with most Flite products, the boards can even be used by pros as a durable and lightweight alternative to our carbon fiber boards.’ As of publishing the story, the Flite AIR and AIR PRO are priced at 6,995 USD.

Fliteboard has been developing this inflatable technology since 2018

detailed view of the new inflatable Fliteboard with electric hydrofoil

[ad_2]

Source link

MOLLIE: A Boutique Hotel in Aspen Channels the Colorado Ski Town’s Bauhaus Heritage

[ad_1]

Located in downtown Aspen, MOLLIE Aspen is a new 68-room boutique hotel with an understated luxury that takes its cues from the town’s historic ties to the Bauhaus movement. In what is collaboration between Colorado practice CCY Architects and Brooklyn-based multidisciplinary design firm Post Company, who are responsible for both the interiors and graphic identity, the hotel’s design is rooted in simplicity and utility as much as materiality and craftsmanship. Reflecting Aspen’s cultural heritage, a vernacular soulfulness pervades the Bauhaus-inspired interiors thanks to the use of natural woods, earthen ceramics and hand-dyed textiles. Part peaceful retreat, part vibrant communal hub, MOLLIE’s relaxed guest rooms are complemented by convivial public spaces — namely a lobby bar and restaurant with year-round outdoor seating, a laid-back all-day café, and a rooftop pool and terrace which becomes an intimate lounge by night — designed to bring people together, just like Mollie Gibson, a 19th century local figure known for her restless enthusiasm for the outdoors which the hotel takes its name from.

The hotel is nestled between two distinct districts, Aspen’s commercial core and the historic West End, a predominantly residential area dotted with 19th century Victorian homes. CCY’s design responds to the liminal setting by using brick for the ground floor and wood for the upper floors, the former a nod to the town’s commercial buildings, the latter to the town’s residential properties. The brickwork’s dark hue echoes the rocky landscape of the surrounding Elk Mountains while the random widths of the vertical wood cladding emulate the slender rhythm of the forests that pepper the region. Although the hotel’s footprint is relatively small, the architects broke down the building mass into smaller cubic volumes that rhythmically jut out in line with Aspen’s historic lot widths with tall windows echoing the proportional fenestration of the Victorian housing stock.

[ad_2]

Source link

Hotel AKA Alexandria Fuses Minimalism + Mid-Century Aesthetics

[ad_1]

Hotel AKA Alexandria is a minimalist boutique hotel located in Old Town Alexandria, Virginia, designed by Piero Lissoni. The property, just a 20-minute drive from Washington, D.C. and 10 minutes from Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport, showcases a fusion of modern minimalism and mid-century aesthetics.

Guests are welcomed by the hotel’s floating staircase, a Lissoni signature, which presents a blend of dark steel and distinctive lines leading up to the terrace. The accommodation spaces, including rooms and suites, offer a residential feel with high-end amenities and furnishings.

Lissoni’s design sensibly merges contemporary elements with the quaint, brick-lined environment of Old Town. The common areas are characterized by sleek lines and dark tones, reminiscent of Japanese minimalism, and furnished with pieces from acclaimed designers like Lema, Living Divani, and Porro.

A standout feature within the hotel is the Mamacloud by Frank Gehry, a light fixture that resembles a cloud, floating above the a.lounge bar. This piece, made by Belux in collaboration with Kreon Lighting, introduces an element of nature’s unpredictability into the architectural setting.

Photography by Jeffrey Totaro.

[ad_2]

Source link

‘Living in Brixton allowed me not to be judged non-stop’: Zineb Sedira, the artist who makes people feel at home | Art

[ad_1]

In the late 1960s, in a poor suburb north of Paris, Abdelrahman Sedira was in the habit of taking his little girl Zineb to the local cinema on his day off. Abdul Sedira worked as a cleaner in a factory. He was illiterate in both French and his native Arabic having hardly been to school, but he and Zineb shared a love of film. The cinema was the place where Abdelrahman met other working men, some like him from Algeria, some also with their children in tow. Father and daughter’s favourite films were spaghetti westerns, or schlocky Egyptian epics about Cleopatra. In place of subtitles an Arab speaker might stand at the front and shout out ad hoc translations. Those afternoon adventures stayed with Zineb Sedira, opened up worlds for her.

Fast forward to 2022, and that same little girl, now a resident of Brixton in south London, is selected to represent France at the famous Venice art biennale. There are some protests at her appearance from conservative voices in Paris – what does this daughter of Algerian immigrants, an exile in London, know of French culture? But Sedira doesn’t listen to any of that. As part of her pavilion, she recreates the rough old cinema in Gennevilliers in which she and her father had spent those 1960s afternoons. And she doesn’t stop there. She locates films of Algerian émigrés like her father arriving in France in hopeful berets and somehow inserts herself in among them. She brings to life a famous celluloid bar-room in exacting detail – in order to recast a celebrated, taboo-breaking scene from the movie Le Bal in which a Parisian woman dances the tango with an Algerian man (Sedira sashays as the woman). And she remakes in loving homage the living room in Brixton, with its retro 1960s furniture, its vinyl records, its film posters, in which these vivid memories had settled in her head.

Critic Laura Cumming, writing in this paper, described Sedira’s Venice show as “the wildfire hit” of that pioneering “women’s biennale”; a “living enchantment” that “weaves the family story into postcolonial history” and uses “the seamless flow of film to question what is real and what is fiction”.

Next week those Venice rooms and films are once again being recreated – with some added reference points from that personal history – this time in the Whitechapel Gallery in London’s East End. The venue is a natural one for Sedira’s seductive inquiry into the nature of displacement and assimilation, memory and forgetting – it has been for generations a refuge and showcase for waves of different local communities in adjacent Brick Lane. In a time of depressing political obsession with the “cultural threat” from immigration, Sedira’s art examines and celebrates the romance of moving and mixing and making new.

Last week I sat upstairs with her in the gallery, while staff knocked together her living room below, and talked about some of that history. The show has a particular emotional relevance for Sedira, because her father, the man who “planted those seeds in heart and mind” died in December. Sedira, 61, is just back from Paris, where she now has a studio as part of a city initiative to promote “homegrown” artists. “My identity was already a little complex,” she says, with a smile, “but I’m still getting used to two homes and studios. I woke up this morning, back in Brixton, and I thought I was still in Paris. And if I’m cooking something in the Paris kitchen I’m looking for my olive oil in the place it is in England.”

Has having thousands of biennale visitors wandering through her London living room, sitting on her sofas, reading her books, changed the way she feels about the real thing?

“A little. And people obviously often have deja vu when they visit – or if I do a Zoom call they know the background very well. But it’s still as it was. And I live in it, as before.”

It was partly her interest in collecting furniture and photographs from the 1960s that established Sedira’s artistic practice. She’d look in flea markets or on eBay for “lived objects” that might tell a political or postcolonial or feminist story. That habit became a full-on conservationist’s obsession with projects to preserve archive film from the 1960s, in particular from the “golden age” of Algerian cinema that followed the end of the colonial war with France and independence in 1962. Sedira is fascinated by the way Algiers became briefly the centre of political film-making at that moment, with the independent government, for example, funding such lasting masterpieces of cinema as The Battle of Algiers by Italian director Gillo Pontecorvo.

That film was not one Sedira and her father ever saw – it was banned in France for several years and the subject of terrorist threats when eventually released. The artist first watched it when she came to art school in London in the early 1990s, and a few of her parents’ stories of the past fell into place.

She made a film piece called Mother, Father and I in which her parents talked first about their life in French Algeria, and their involvement in some actions by the resistance movement – and then about their decision to come to live in France, to choose the country of their coloniser. “They explained it in very simple words,” Sedira says, “it was for economical reasons, for the family.”

In her childhood, her parents were careful never to say anything negative about France. “They obviously didn’t want us growing up hating France, our home,” she says. “Nevertheless, we could see that there was a problem. I was born a year after Algeria won the war – so you can imagine the racism in France towards Algerians. I grew up with a lot of that racism. As a child, you might not fully understand political conversations [going on] around you, but you still absorb something about it.” She believes those absorbed attitudes and emotions “have sort of started coming out of me now” in later life; she finds herself picking through that past, trying to make sense of it all.

One aspect of that is her experience of two different kinds of assimilation. “France was, is, very much more about integration than Britain,” she says. “You were required to almost forget everything you come from, and adapt to the French identity, the French culture, the French language. Though my mum, who was at home, to this day doesn’t speak much French.” Still, they were between worlds, adrift in the imaginary homelands they glimpsed on the big screen. “In France we were seen as Algerian, and when we went to Algeria to visit, we were seen as French … ”

In order to understand that, Sedira had a powerful need to be in a more neutral place. She came to London to study art at Central St Martins and the Slade when she was 23. “I started to gain some political consciousness because I could see things from afar … living in Brixton allowed me not to be judged non-stop, for the colour of skin or my background.” That consciousness crystallised when she became a mother for the first time at 28 – she has three children – “and you also want to pass on some knowledge of your culture, of your tradition to them”. In many ways, the question of what of the past to hold on to and what to let go of, remains the shaping force of her art.

She had a stroke of fortune when she settled in London. Living two doors down from her in Brixton was the artist Sonia Boyce – now Dame Sonia – a pioneer of the British Black arts movement in the 1980s. They became close friends. “Sonia had her first daughter more or less at the same time as I had my son,” Sedira recalls, “we were going to the one o’clock club together, to the park. And we had a lot of conversations about art. I was accepted into what had been the Black art movement – not least because Frantz Fanon [the Black political philosopher and radical] had taken up the cause of Algerian independence. The struggle was the same”. She and Boyce set up a women’s art group, which met once every two or three weeks, quite often in Sedira’s now famous living room. “Sonia became a kind of mentor because she’s so generous,” she says.

In 2022 that three-decade friendship had an impossible kind of Hollywood ending. At the same moment that Sedira was chosen to represent France at Venice, Boyce was chosen for the British pavilion next door – their Brixton neighbourhood transported to the grand canal. Boyce’s show also mined cultural memory and the power of collaboration – giving a voice to the often forgotten role of Black female singers in British cultural life; Feeling Her Way was awarded the top Golden Lion prize at the festival.

Sedira and Boyce loved the serendipity. “From the outset, I said I want to make a bridge between the French and British pavilions,” Sedira says. Boyce appears in the film about film that Sedira shows (now in Tate Britain’s collection), Dreams Have No Titles, which explains her life and her practice. “It came completely naturally that Sonia would be in the film,” she says, “and another coincidence, the film was directed by Gilane Tawadros [since made director of the Whitechapel Gallery]. It made perfect sense that those two girlfriends of mine would have a conversation together in my living room in Brixton – that’s what we always did.”

When they were first having those conversations, with kids running about, did she ever imagine the kind of storyline that followed?

She laughs. “No, never! I couldn’t even go to any exhibitions or show my work: I didn’t have much money and I had three children. But I think with art you just keep doing it, until you get an opportunity. The big break for me was to be invited to be part of the group show in the first African pavilion in Venice, in 2003.” Ironically, she says, there was a growing interest in artists with Muslim or Middle Eastern heritage after 9/11 and the invasion of Iraq. “People wanted to hear those voices suddenly … there were symposiums, conferences and I was part of that.”

Her own relationship with that part of her background is relaxed. “I’m not a practitioner of Islam at all. But, you know, I say I am Muslim as an identity.” Her parents were believers, but generally secular in their lives in France. Over the years her mother adopted a face covering when she went back to Algeria, which was quite alien to Sedira. “When we landed she would get this out of her suitcase – a scarf and veil. Suddenly, she became lost. Literally, sometimes we would meet somewhere and there would be four or five women with the same attire and you wouldn’t know who she was.” There was never any suggestion that Sedira should do the same; indeed, when her sister wore a headscarf once in Paris, their father was furious: “That’s not what we believe in.”

I wonder if Sedira’s inspired curation of the past has an audience in Algeria as well as in France and Britain. She suggests that it has, up to a point. “The art scene is very limited there. But I have had four or five shows.” She is more concerned, on visits to archives in Algiers, by the way in which the record of the years of revolutionary optimism is slowly decaying. There is a nostalgia in her efforts to preserve it, but it also represents a political act, trying to maintain a thread of connection back to those 1960s dreams.

“For me, it’s telling the world that despite everything that has happened since, that moment did exist. With the rise of terrorism in Algeria in the 90s the country went downhill. The culture, the cinématique [film school] that had been created in the 1960s was killed, basically.”

In this sense, you understand her love of the materiality of old film reels and archive records as a kind of defiance, a personal rage against the dying of the light, an insistence to keep protesting, keep dancing. Film-making during the war for independence was not only part of the struggle, it was literally a struggle.

“Because it’s so much easier now to film something, on a phone or whatever, we forget how hard it was,” she says. Each of the film reels and sets of transparencies from that time represents a proper commitment, not least in terms of heavy lifting. “These people were taking a big 45mm or 60mm camera into a war zone, with a tripod. What interests me is the fact that culture was used and will always be used as a protesting tool.”

In the current political situation in all three of Sedira’s homelands – Algeria, France and the UK – that commitment seems as urgent as ever.

“I think there is obviously a big something going on around these questions [of immigration and identity] again,” she says. “It feels like something not nice is happening in all Europe.” She is alarmed by the prospect of another Marine Le Pen election run next time around. “I wouldn’t point my finger at France particularly, because you see it everywhere. But of course France allowed extreme right parties to exist, so now we’re faced with it. If she comes into power, which a lot of people are saying she might, then of course it will be awful, especially for the immigrants.”

Sedira’s work, in a small way, offers an alternative to those divisions; a complicated, creative personal history that becomes a symbol of the ways in which life is not about division. How, I wonder, does she hope people will react when they arrive at her show?

“Well in Venice,” she says, “people were smiling, getting on the dancefloor. I think it was successful because it was a participatory project. It was an invitation to bring your own story. People seemed to feel like they had walked into a doll’s house, a place to play. You could go in the kitchen, and nobody was saying, don’t do that, you could sit in the living room. So a lot of people said they came out with a big smile on their face.”

Just like the artist, you might say, they finally felt right at home.

[ad_2]

Source link

Paul McCartney Talks About His Beatles Photos Coming to the Brooklyn Museum

[ad_1]

They are now a collector’s trove — Paul McCartney’s own photos, shot 60 years ago, when the Beatles took Europe and America by storm: images of screaming fans (one carrying a live monkey); a girl in a yellow bikini; airport workers playing air guitar, and unguarded moments grabbed from trains, planes and automobiles.

McCartney, now 81, doesn’t like to sit still and reminisce about the past, so he chatted while driving home from his recording studio in Sussex, England. “My American friends call these small, one-way lanes ‘gun barrels,’” he said, warning his interviewer that at any moment the signal might die (it did). In the end, it took two days to complete a coherent conversation about the breakthrough period when the Beatles went viral, captured in the traveling exhibition “Paul McCartney Photographs 1963-1964: Eyes of the Storm,” which features 250 of his shots. Currently it’s at the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Va., and comes to the Brooklyn Museum May 3-August 18. (Don’t be surprised if the artist shows up for the opening.)

It was McCartney’s archivist, Sarah Brown, who found 1,000 photographs the musician had taken over 12 weeks — from Dec. 7, 1963, to Feb. 21, 1964 — in the artist’s library.

“I thought the photos were lost,” he said. ‘‘In the ’60s it was pretty easy. Often doors were left open. We’d invite fans in.” Even the recording studio wasn’t a safe space. “I was taking my daughter Mary to the British Library to show her where to research for her exams, and in one display case I saw the lyric sheet for ‘Yesterday,’” he said. A sticky-fingered biographer had swiped the original from their studio.

Rosie Broadley, a senior curator at the National Portrait Gallery in London, where the show was inaugurated, said, “His photographs show us what it was like to look through his eyes while the Beatles conquered the world.”

McCartney won an art prize at school and practiced photography with his brother, Mike (who later became a professional photographer). He graduated to a 35 mm SLR Pentax camera when the Beatles hit it big.

“It was the most sophisticated hand-held camera of the era. It would be like having the latest iPhone today,” Darius Himes, Christie’s international head of photography, said, adding: “We were all quite surprised by Paul’s sophisticated eye, and his awareness of trends in the visual arts. The yellow bikini shot is like a striking mix of Stephen Shore, William Eggleston and William Klein.”

The Beatles traveled with a flock of cameramen and were not shy about gleaning tips. McCartney admitted some of his earliest shots in the exhibition are a little fuzzily focused. “I console myself that one of my favorite photographers, Julia Margaret Cameron, also liked soft focus,” he said.

“His photos get better as he practices,” Broadley noted. The exhibition, and its accompanying book, take visitors on a whirlwind trip through six cities beginning in Liverpool and London, and ending in Miami. The images from the British leg are exhibited in small ‘‘austerity’’ walnut frames, to indicate Britain was still in throes of a postwar recession. The Fab Four might look nervous in these photos, but they had already reached stardom on their home turf, having bagged three No. 1 singles and met the Queen.

After a brief stint performing at the Olympia in Paris, alongside Sylvie Vartan, they heard that “I Want to Hold Your Hand” was No. 1 on the American charts and sped to New York. The crowning moment in America was their live television debut on the “The Ed Sullivan Show” on Feb. 9, 1964, singing five propulsive pop hits — an event watched by 73 million people.

In Miami, McCartney’s photos burst into Kodachrome color and the newly minted celebrities seem to bloom in glamorous new surroundings: lounging poolside, sipping scotch and riding around in motorboats. By April, the Beatles’ songs held the top five spots on the U.S. Billboard charts.

Musing on the images, he said, “There is an innocence to them,” adding, “I think it was a lot more fun than it was. We worked probably 360 days out of the year.” It was an all too brief halcyon period. Two and a half years later, the Beatles stopped touring. The logistics, the screams, the armored cars, had become a nightmare.

Like most successful artists thriving past retirement age, McCartney has projectitis. He’s working on a new album with the producer Andrew Watt (“Hackney Diamonds”), and just released the 50th anniversary remaster of the Paul McCartney & Wings classic “Band on the Run.” “His live shows continue to be of such high voltage one half expects him to burst into flames,” the Irish poet Paul Muldoon wrote in McCartney’s recent book, “The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present.”

His next project is organizing a gallery sale of some of his photographs. “It’s a process I like,” he said, describing the joy of curating. “I’ve done it a few times with Linda’s work” [a reference to his first wife, the photographer, Linda Eastman]. His current homes, shared with his wife Nancy Shevell, are adorned with images by Linda and Mary, though, curiously, none of his own. But that may change. ‘‘The sale,” he said, “will probably encourage me to get some for myself.”

Here are edited excerpts from our conversation, in which he reflected on popular images in the exhibition.

John Lennon. London, January, 1964

My favorite photos are of John and George. There’s a huge sentimental aspect to them. No one else could have taken this pic. John was a great character. A very different kind of guy to the other boys I knew. We met at the village fete. He was playing with his band. He was a year and a half older than me [and] my first friend who wore glasses. He was always taking them off and polishing them. I found it fascinating. He’d take them off in public, which rendered him half blind. Onstage, he just stood there and gazed out into the blackness. Maybe it helped him focus on playing.

John, George and Ringo backstage in their dressing room. London, 1963.

We began by playing in really crummy little clubs and bars in Liverpool and Hamburg. In Germany, we slept in a little room, with a Union Jack flag for a blanket. Back in England, it started to get a little better. We played in ballrooms, got radio work and then TV work. It was like a staircase ascent for us. What nobody realized is, by this time [seven months after the Beatles’ first No. 1 hit on the U.K. charts], we were really fully formed beasts. We’d come from the postwar years into a Britain that was now experiencing joy for the first time in decades, and we ate it up.

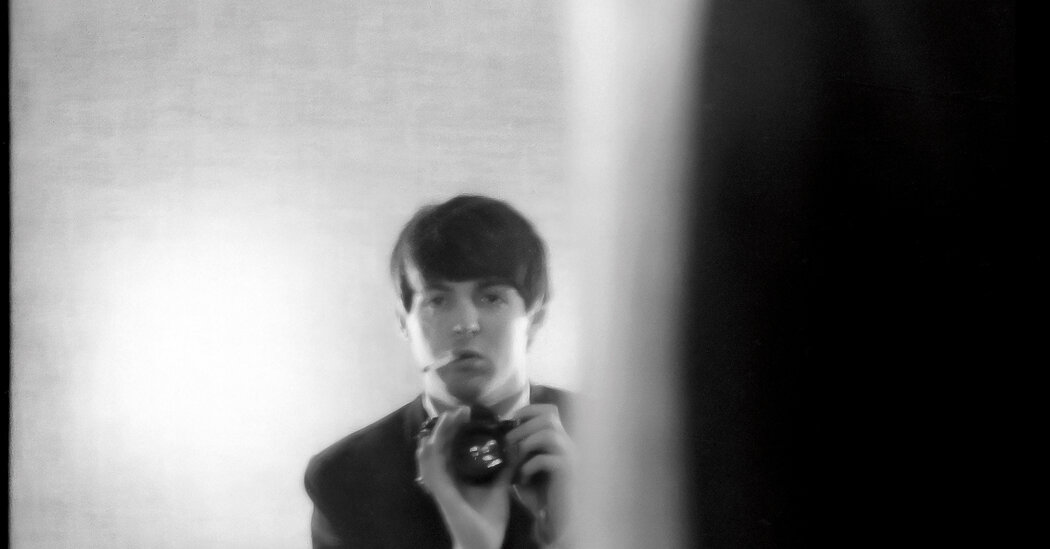

Self-portraits. Paris, 1964.

Our Pentax cameras were probably a gift. There was a lot of artistic black and white photography emerging at that time. We admired David Bailey [who had a Pentax camera], Don McCullin, a stunning war photographer, and Norman Parkinson. When he took our picture, he’d say ‘give me big eyes’ and we’d all play along. I like to shoot through the mirror because things look good in a mirror. We all smoked. Smoking gave us a suave, grown-up feel. We were pretty young. I was just 21.

Ringo Starr. Paris, 1964.

Our aim was always to have fun. I think that communicates itself and became part of the reason we were so popular. It is just a characteristic of Liverpool people to have a laugh. [Paul snapped this shot of Ringo during a staged photo shoot with Dezo Hoffmann, one of their court photographers.] Dezo was a very nice guy. He would give us hints as to the aperture and all the various things needed to make a good photograph.

Fans welcoming the Beatles at Central Park. New York, February 1964.

Here’s a pic of Beatles fans acting like they should. … Going crazy! We didn’t know what we were gonna get in America; if anyone would turn out to meet us. On the plane over, the pilot radioed ahead and was told there were gangs of fans waiting. [Over 4,000 screaming girls held back by 200 policemen.] Manhattan was big, tall, loud and brash. There were stories of fans breaking into our room at the Plaza Hotel. Those were more stories than reality. We probably wished it would happen.

Ringo Starr setting up his drum kit during rehearsals for “The Ed Sullivan Show.” New York, February 1964.

We had done television in England, so we were used to it; the cameras and the lights and all that. What we didn’t really know was how important Ed Sullivan was. He was the BIG ONE. There were two stagehands waiting to draw back the curtains for us to go on and one said: ‘You nervous?’ I said, ‘I dunno. Not really.’ He says: ‘You should be. There’s 73 million people watching.’ Then I got nervous. But if you watch that performance, I can’t believe how confident we look. The weird thing about the stage set is Ringo’s [precarious] drum rostrum. I can’t work out how he got up there.

Photographers in Central Park. New York, February 1964.

New York journalists thought they were pretty smart and I’m sure they were used to handling dumb pop stars. We had a lot of fun with them, especially at the news conference at J.F.K. [Airport]. We gave as good as we got. It became a game of who could come up with the smartest answer. Often it was the truth. Someone asked George, ‘Do you ever get your hair cut?’ He said, ‘Yeah, yesterday.’ And he’d been to the barber’s the day before.

Unknown man. Taken from the window of train from New York to Washington, D.C., February 1964.

We loved music and performing. It beat working in a factory. A few years before these pictures, we’d all been fully immersed in working class life in Liverpool. I have a fascination with working class people like this man [a railroad worker caught from a train en route to Washington, D.C.]. Working class people are the smartest people I’ve ever met. My cousin Bert [Danher] was an insurance salesman, but he also compiled crosswords for The Guardian and The Times. The photography I admire is spontaneous, like the work of the great [Henri] Cartier-Bresson. It was good to just grab shots on the run. We didn’t have time to think.

Unknown girl. Washington, February 1964.

Some of my favorite photos are of fans. I really like this one of a young girl with a headscarf looking in a Zen-like manner into my camera. I took it and never looked at it again until I did a print [for the National Portrait Gallery exhibition]. When we started blowing up the images, we got to see all the individual characters. In one photo, at Miami airport, there’s a woman holding up a monkey. You wouldn’t get that past health and safety these days.

George Harrison. Miami Beach, February 1964.

This is George living the life in Miami. [McCartney switched to Kodachrome to record the group’s antics in Florida.] Miami felt like wonderland. These pictures were taken at a time when we were all young and beautiful. I mean these are good looking boys, you know! From this perspective, I feel very blessed to have not only known these guys, but to have worked with them and done such great things with them. I feel very blessed.

[ad_2]

Source link

richard neutra’s restored mid-century home in california is now up for rent

[ad_1]

richard neutra’s Taylor House in california is available for Rent

Perched on a quiet hill near the Verdugo Mountains Open Space Preserve, just north of Glendale, California, lies the Taylor House, which is now up for rent at $10,000 per month. This carefully restored mid-century home was designed by Richard Neutra in 1961 for Maurice and Marceil Taylor. Nestled in Whiting Woods, the residence has undergone a thorough three-year restoration, honoring Neutra’s original design for a seamless indoor-outdoor living experience. Occupying 1,477 square feet (137 square meters), this two-bedroom, two-bathroom home reflects Neutra’s belief in architecture’s therapeutic qualities, featuring massive plate glass sliders that integrate the indoors with the natural surroundings.

all images by Paul Barnaby

stepping inside this restored mid-century home

Behind its humble facade, Richard Neutra’s Taylor House offers privacy amidst oak trees. Upon entering the house, visitors are greeted by a gradual reveal of the lush scenery, framed by a central fireplace and art wall, leading to the main living area with cork floors and panoramic glass walls. The kitchen, with a mahogany bookcase separating it, showcases restored Frigidaire appliances and cabinets, maintaining the home’s original character. Vintage chrome fixtures and intricate tiles in the primary bedroom’s bathroom add to its charm. Modern amenities like a full-size laundry area, HVAC system, two-car carport, alarm system, and outdoor spaces ensure comfort and convenience. Conveniently located near dining, shopping, and institutions like JPL, Cal Tech, and Art Center, the Taylor House offers a peaceful retreat with easy access to downtown, Pasadena, and the San Fernando Valley.

mid-century Taylor House is now available for rent

the house seeks to blur the boundaries between in and out

the home underwent an extensive three-year restoration, respecting Neutra’s initial design

[ad_2]

Source link

Artist Eva Jablonsky’s Engrossing Search for Balance and Harmony Through Abstract Painting

[ad_1]

Geometric abstraction is at the core of your painting practice. How did this graphical language evolve and how does it reflect you as an artist?

I've always loved geometric shapes, especially in architecture and design. I was never a fan of squiggles. The straightforwardness and clarity of geometry, its repetition – there has always been something very balanced, harmonious and neutral about it. It has a calming effect on me.

You use a limited colour palette of black, white and earth tones. Why? Is this an aesthetic or conceptual choice?

It’s difficult to describe in words. It's neither aesthetic nor conceptual. Although I personally find earth tones and neutral colours like white and black aesthetically pleasing, it’s more of an emotional choice. These colours have a calming effect on me; just like geometric shapes, they evoke a sense of permanence. In life, everything is constantly changing, but there are things that you want to hold on to, that are beautiful just as they are, for example a friendship that has lasted for decades, a place that you always like to return to or the love of your life.

Colours, on the other hand, have a different energy for me. They are dynamic, alive. That's nice, but it's not something I want to achieve with my art. This is something I realised early on, although, admittedly, I did experiment with colour a little at the beginning – one of my first paintings is actually pink and blue. It's now in the basement of my studio. One day I will paint over it.

[ad_2]

Source link

The NaughtOne Percy Lounge Chair Is Totally Tubular

[ad_1]

With its colorful flowing tubular steel frame design, the NaughtOne Percy Lounge Chair looks like a chair that would be right at home situated within the Centre Pompidou. Like Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers’ example of ‘inside-out’ architecture, the chair, designed by independent furniture designer and founder Nicole Marion, of Studio Marion, exhibits an inviting honesty that tames the industrial into something almost curvaceous.

“When designing Percy, I was drawn to the combination of hard metal and soft upholstery,” explains Marion. “I wanted to play with visually softening the metal to create a cohesive, curvaceous look. I love working with metal and steel as it’s an incredibly durable, industrial material, but it can also bend and flow.”

The chair’s chunky tube frame appears as one continuous support system for the Percy’s plush upholstered cushion, giving the chair an inviting degree of support across the seat and back. Partnered with an extensive palette of colorful finishes, upholstery options, and a low profile, the design strikes a totally tubular balance between durability and comfort.

“The design we landed on has a timeless look, almost as if it’s always existed. But it’s also unique – and can be dressed up or down, easily adapting to many environments and personal styles,” says Marion.

Information about pricing and how to purchase the Percy Lounge Chair from British furniture company NaughtOne is available here.

[ad_2]

Source link