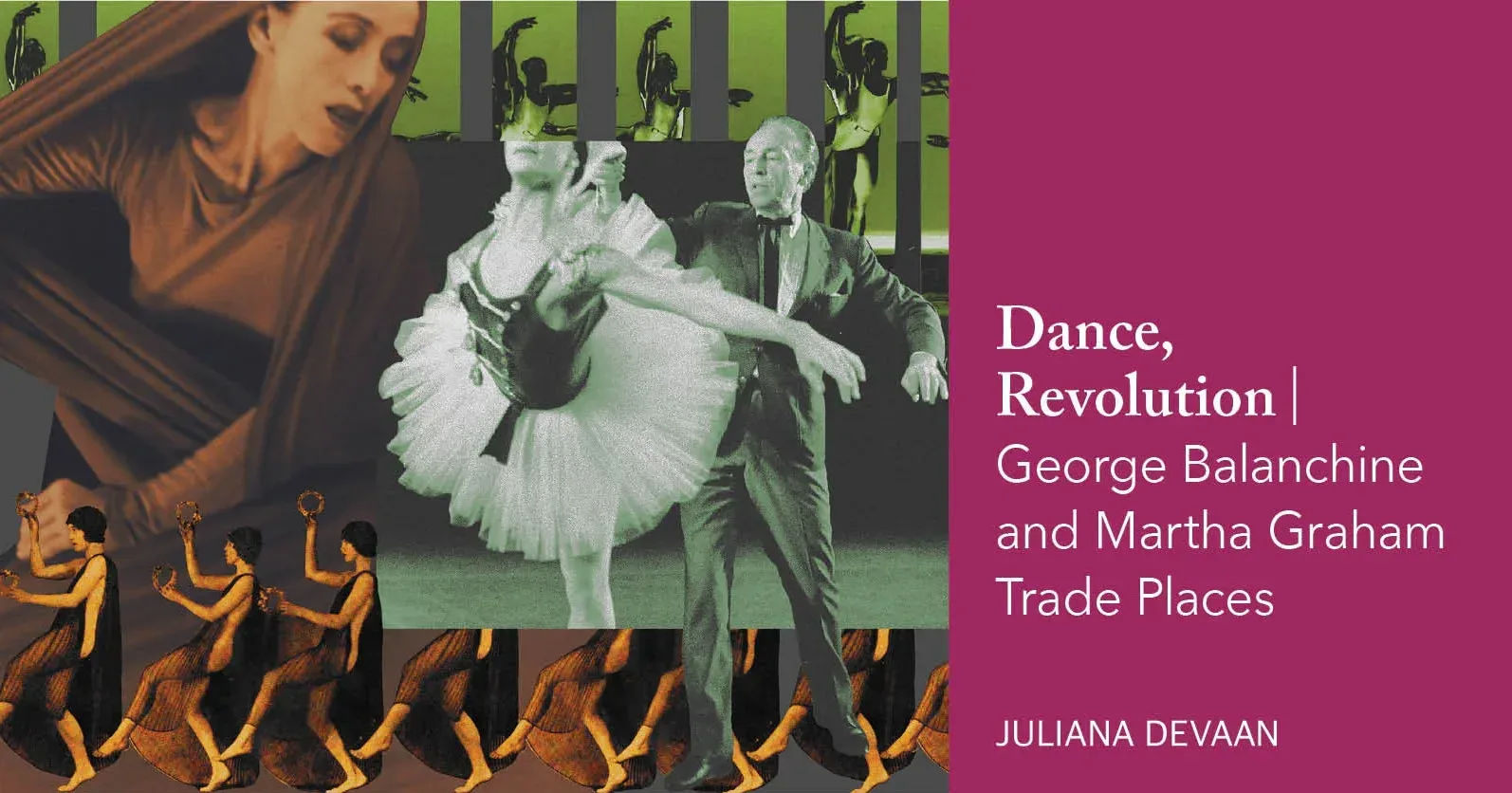

“Dance these days — spring ’59 — is decidedly split into two main factions,” wrote the dancer Paul Taylor: neoclassical ballet, a modernist update of classical ballet, and modern dance, which broke free of ballet’s strictures to use movement as an expressive tool. These two genres were epitomized by the work of the choreographers George Balanchine and Martha Graham, respectively. “So when it’s announced that the two giants will collaborate on a new work,” Taylor continued, “it comes as a startling surprise.” That piece, titled Episodes, premiered on May 14, 1959, at New York’s City Center of Music and Drama, to music by Anton Webern. Sixteen thousand fans were expected to turn up to see the co-creation.

But the performance was not, as some may have hoped, a syncretic blend of ballet and modern dance. Balanchine and Graham instead choreographed separate sections that reflected their signature styles. Balanchine presented a plotless ballet motivated by the formal considerations of Webern’s score; Graham a dramatic, narrative interpretation of Mary, Queen of Scots in the moments before her beheading. Taylor, a Graham dancer loaned to Balanchine in the spirit of collaboration, recalled that whereas Graham spent hours in the studio explaining the ideas, references, and emotions behind her choreography, Balanchine was economical with his rehearsal time. When he did speak, it was often in the form of aphorism. Taylor, seeking guidance on how to perform, once asked what his solo in Episodes was about, and Balanchine replied, “Is like fly in glass of milk, yes?” While Balanchine watched performances silently from the wings, Graham took the stage (just three days after her 65th birthday) as the ill-fated queen.

At the time of the premiere, Graham was the more established choreographer, and her contribution to Episodes was met with greater acclaim. Even though she was clearly declining in ability and stature, she was still renowned as a virtuoso performer and considered the mother of modern dance. Yet put side-by-side with Graham’s, Balanchine’s work appeared more abstract and modernist. His leotard-clad dancers flexed their feet, twisted their bodies, and moved with angular precision to Webern’s atonal music; hers donned full costumes to tell a story through gestures less suited to the radical composition. In the wake of Episodes, Graham and Balanchine swapped trajectories: like the bygone queen she embodied onstage, Graham became an archaic figure, the personification of modern dance history, while Balanchine became the emblem of twentieth-century American dance.

Today, Balanchine endures as the field’s most dominant — and most documented — figure. More than forty years after his death in 1983, there remains an entire Balanchine industry, which continues to churn out panel discussions, memoirs, podcasts, and documentaries. The New York City Ballet (NYCB), the company he cofounded in 1948, is the largest dance organization in the country, and his works are performed regularly around the world. The Martha Graham Dance Company (MGDC) is a comparatively miniscule endeavor, performing in New York about once a year. The NYCB’s 2022 tax filing reveals it brought in $85.6 million that year, and holds $313 million in total assets. By contrast, the MGDC’s revenue was $3.64 million, and its assets measure $1.53 million.

During the 2023-2024 season, both companies are marking impressive milestones. NYCB celebrated its 75th anniversary with a fall season at Lincoln Center, featuring works from the company’s inaugural performance; the Martha Graham Dance Company has planned programming from 2023 to 2026 to honor a hundred years since Graham debuted her original choreography and founded her dance school in New York. Balanchine and Graham are also the subjects of new biographies: Jennifer Homans’s Pulitzer Prize and National Book Critics Circle Award finalist, Mr. B: George Balanchine’s 20th Century, Neil Baldwin’s Martha Graham: When Dance Became Modern, and Deborah Jowitt’s Errand into the Maze: The Life and Works of Martha Graham.

While these books provide robust portraits of their subjects’ personal idiosyncrasies and artistic innovations, they largely avoid asking and answering structural questions about the history of dance. Yet if the intertwined fates of Balanchine and Graham tell us anything, it should be that trajectories of dance styles and legacies of choreographers are just as much the products of money and institutional support as of artistic talent. NYCB’s longevity and Balanchine’s prominence are the result of more than 75 years of hard work by networks of patrons, critics, and devoted teachers who, both before and after his death, have turned Balanchine into a godlike figure, and kept his movement alive in the bodies of dancers. Graham, who developed a discipline arguably more original than Balanchine’s twist on Russian classical ballet, never benefited from such vast institutional backing. In overlooking the forces that produced their subjects, these biographies perpetuate a long-standing unwillingness among dance historians to think about the forces of money and power that have shaped American dance.

It was never Balanchine’s goal to start a school of American ballet. That mission belonged to Lincoln Kirstein, the American aesthete and cultural impresario. During the summer of 1933, Kirstein traveled to Europe and began to formulate the idea of starting a ballet company and school stateside. At the time, ballet in America was a foreign import, whereas modern dance had established itself as the country’s novel, nationalist form, originated and practiced by Americans. Kirstein would need a charismatic, talented choreographer who could update the tradition for modern times, with an adopted American sensibility. He found one in Georgi Melitonovich Balanchivadze, who would come to be known as George Balanchine.

Born in 1904 in St. Petersburg, Balanchine studied ballet at the Imperial Theater School until it shut down in 1917 amid the Russian Revolution, during which he sometimes stole food to survive. In 1918, the school reopened, and Balanchine soon graduated and began to dance and choreograph professionally, founding a small kollektiv which performed his more experimental work. In 1924, the group was granted permission to tour Europe, and the dancers eventually made their way to Paris, where Balanchine joined the Ballets Russes as a choreographer. When its director died in 1929, the company disbanded and Balanchine floated around Europe, including London, where Kirstein saw his choreography. As Kirstein later recalled, he was so taken with Balanchine that he “proposed an entire future career in half an hour.” Desperate for a stable gig and the opportunity to choreograph new work, Balanchine agreed to Kirstein’s scheme and arrived in New York in the autumn of 1933.

Kirstein tapped his network of wealthy friends to find funding for the School of American Ballet (SAB), which opened in 1934. At first, Balanchine did not teach at the school, since he was focused on choreographing. But American audiences were confused by Balanchine’s work. Apollo, now considered a classic in his oeuvre and one of his first experiments in neoclassicism, depicted the muses of poetry, mime, and dance instructing the god of music with pared-down aesthetics and steps. When it premiered in America, it was described by one reviewer as “bizarre,” and bordering “on the line of insanity.” Kirstein and Balanchine’s first company, the American Ballet, populated by SAB students, folded in 1938. Balanchine absconded to California while Kirstein embarked on a second attempt, Ballet Caravan, which collapsed several years later. Finally, in 1946, Kirstein and Balanchine began Ballet Society, the company that would become the NYCB. By then, Balanchine’s choreography had become more recognizably American, acquiring accents of jazz and tap from popular entertainment. In the late 1930s, out of financial necessity (and simple curiosity), Balanchine had taken jobs outside the realm of ballet, on Broadway and in Hollywood. Working with black dancers and choreographers on those projects, he picked up syncopations and stop-times, which he brought back to ballet, grounding his developing American idiom.

Kirstein planned to fund Ballet Society half through personal money and half through ticket subscriptions (though tickets never covered more than a small part of expenses). In a letter, Kirstein explained that the company’s purpose was to support Balanchine: “to do exactly what he wants to do in the way he wants to do it.” When some critics and friends voiced their disapproval of the company’s first performance, Kirstein was “very upset.” It was Martha Graham, his guest at the premiere, who encouraged him to persevere. To keep the company alive, Kirstein leveraged his connections to raise money and garner press. In 1948, Ballet Society became the New York City Ballet when Morton Baum, a powerful lawyer and political insider who implemented New York City’s first sales tax, invited the company to become the in-house ballet of the City Center of Music and Drama, which he had founded with Mayor Fiorello La Guardia five years earlier. At City Center, Balanchine’s signature dynamic, zipping, angular, mostly plotless choreography solidified and became recognized by audiences and critics as the embodiment of American ballet. Though Balanchine was able to choreograph across genres, from romantic story ballets to Broadway-inflected character work, his leotard dances were greeted with critical acclaim. Stripped down to their black-and-white practice clothes, Balanchine dancers became the medium for formalist experimentation.

Agon, which premiered in 1957, was the apotheosis of Balanchine’s leotard ballets. Set to a twelve-tone score by Igor Stravinsky, the dance’s climax was a duet between Arthur Mitchell, the first black dancer with NYCB, and Diana Adams, a white ballerina. They whipped their legs and contorted their bodies into yearning, tensile poses, most famously a split in which Adams wrapped her leg around Mitchell’s neck. It was a dance about anxiety, drawing on the contrast between black and white and the discordant sounds of Stravinsky’s score, but it also resonated with widespread preoccupations with the ongoing civil rights movement and escalating Cold War. Balanchine had “publicly cut through the twisted knot of race relations,” an NYCB dancer later wrote. Yet Balanchine and others maintained that the piece had nothing to do with politics. In the program notes, Balanchine called it a work of “symmetrical asymmetry,” “an IBM electronic computer,” and “a machine.” Edwin Denby, a critic who championed Balanchine, wrote that “the fact that Miss Adams is white and Mr. Mitchell Negro is neither stressed nor hidden; it adds to the interest.” To Denby, Agon was a perfect dance because it captured Balanchine’s buoyancy, momentum, pulse, and spontaneity. It provided “direct enjoyment of dancing as an activity,” an “objectivist” approach to ballet. In their writing, both Balanchine and Denby took the prescribed Cold War stance that art should have nothing to do with current events, and that American ballet was exceptional because it was about physical motion unburdened by dramatic narrative or ideas. Agon contained the qualities that made Balanchine so popular: it broke apart classical ballet while retaining its core principles and technique, embodied ideals about American character, and reflected a politics of racial liberalism even as ballet remained white and ostensibly apolitical. It was the right dance for the moment, and critics and audiences took it as a sign that they should bet on Balanchine.

Though City Center drew reliable audiences — artists and intellectuals, as well as working- and lower-middle-class viewers attracted by the venue’s cheap tickets and resulting reputation as the “people’s theater” — there was always financial precarity. Subsidies from Kirstein himself kept the company afloat, as did extended European tours, but what really saved City Center and NYCB in the early 1950s was Kirstein’s relationship with the Rockefeller Foundation. Kirstein was close friends with Nelson Rockefeller and John Marshall, who ran the foundation’s Division of Arts and Humanities and gave City Center a $200,000 grant, taking the organization from near collapse to security with a single check.

Money from the Rockefeller Foundation contributed to the creation of several ballets at City Center, including Ivesiana, Western Symphony, and, most crucially, The Nutcracker. Kirstein was eager to stage a full-length story ballet — more popular and lucrative than plotless one-acts — and Balanchine suggested Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker, which had premiered in 1892 at the Maryinsky Theater in Russia. The 1954 production of The Nutcracker was also a vehicle for Balanchine’s hardened anticommunism. Scarred by his experiences of violence, hunger, and sickness during and after the Russian Revolution, Balanchine embraced America as a repudiation of the Soviet Union. As Jennifer Homans, founding director of NYU’s Center for Ballet and the Arts, argues in her biography, Balanchine’s choreographic taste evolved during the 1950s as he increasingly positioned himself against Soviet ballet. Balanchine’s version of The Nutcracker’s opening party scene presented a romanticized, bourgeois family enjoying Christmastime, in contrast to the original Russian version’s imperial scene of a wealthy family and their servants. By 1958, when he choreographed Stars and Stripes, his patriotism had become explicit. The piece featured groups of dancers, called “regiments” performing “campaigns” to brass, militaristic music, as well as a pas de deux inspired by Dwight Eisenhower’s romance.

The Nutcracker was “a smasharoo,” in the words of Kirstein. When the ballet appeared on television in 1957 and 1958, it broadcast Balanchine and NYCB around the country, becoming a national tradition and providing a reliable source of income for the company. Foundation money, too, continued to flow to NYCB. In the late 1950s, the Ford Foundation, which funded anticommunist cultural organizations including the Congress for Cultural Freedom, began to provide Balanchine and NYCB with transformative sums of money. W. McNeil Lowry, the head of the foundation’s Humanities and the Arts program, sent Balanchine to visit ballet studios around the country to observe the quality of dance training and assess how Ford might help. When Balanchine returned, he announced “that we were going to have a ballet company in every state.” Ford donated $100,000 for scholarships at the School of American Ballet and $25,000 for Balanchine to survey the state of ballet instruction in America and generate a “blueprint for optimal achievement.” The scholarship program sent NYCB dancers across the U.S. to mine regional ballet schools for the most promising talent to be brought to New York on Ford’s dime. The Ford Foundation also sponsored workshops for regional ballet teachers in New York, where they trained in Balanchine’s method of movement and instruction.

After the scholarship program and seminars proved successful, Ford recommitted to its support of Balanchine’s vision of American ballet in 1963, granting $7.7 million to ballet education nationwide — at the time, the largest sum ever allocated to dance in America. The money transformed NYCB into a national company, officially elevating ballet above modern dance. $5.9 million was earmarked for NYCB and its School of American Ballet, which stabilized the company, expanded its scholarship programs and teacher-training workshops, and solidified the school’s status as a national institution. The rest went to regional companies affiliated with Balanchine. No money at all was granted to modern dance.

“Thief!” Martha Graham reportedly screamed at Kirstein, when she heard the news. Whatever goodwill had been generated between ballet and modern dance during Episodes four years earlier was gone. “Only dance forms of European origin, the ballet, have been recognized,” she charged. “Nothing has been done to support our dance.”

When Balanchine arrived in America, Graham was already seen as the inventor of an entire genre and an idiosyncratic technique. Styling herself as a high priestess of modernism, Graham looked and spoke like she was in a constant state of performance. Her heavily mascaraed eyes, painted lips — always partially agape as if she were about to whisper a prophecy — and severe yet graceful tone added to the drama. “The center of the stage is where I am,” she said.

Born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania in 1894, Graham moved to California in her youth. As a girl, Graham learned from her father the principle that would guide her work for the rest of her life: “movement never lies.” Though the true source of the maxim is up for debate, Dr. George Graham was an “alienist” who studied nervous disorders, and through his treatment of patients with physical expressions of mental conditions, Graham learned how the body revealed underlying truths. She incorporated Dr. Graham’s lesson into the foundation of modern dance, an expressive art form that used the body to articulate thoughts and sensations for which words were not enough. Whereas Balanchine was interested in the formal qualities of the body in motion, Graham wanted to use the body as a medium to communicate. Starting out, she performed campy dances in vaudeville tours and a Broadway revue, which paid well but held her back from artistic work. In 1926, she broke free of commercial entertainment, with operational support from her partner and accompanist Louis Horst, and presented her first concert of original choreography in New York. Her early work eschewed decorative poses in favor of movements that conveyed emotional states. She invented steps and gestures, like the contraction of the pelvis, which captured the intensity and anguish of modern life. In 1929’s Heretic, a menacing group of women in black dresses stamped out a soloist wearing white in a parable about nonconformity. Graham’s woman in white was the embodiment of the avant-garde reaction to industrialization and the pressure to comply. “Life today is nervous, sharp and zigzag, and often stops in mid-air,” she said to an interviewer. “That is what I aim for in my dances: I do not want to run away from the struggle that is found in the present day of machines, but I want to understand it and express it artistically.” In her essay “Seeking an American Art of the Dance,” from 1930, she argued for a distinctly American form of dance that prioritized individualism, a sense of virile intensity, and a focus on movement itself.

Like Balanchine’s American ballet, Graham’s modern dance relied on institutional support. In the 1930s, modern dance found legitimacy and financial backing at Bennington College in Vermont, where Graham, along with other choreographers, taught classes and staged works. Bennington, which opened in the middle of the Depression, started a summer dance course to bring in money outside of the school year. The program facilitated the spread of modern dance around the country, as teachers and students took Graham’s name and technique back home with them. Modern dance’s national reputation was also boosted by The New York Times’s first full-time dance critic, John Martin, who wrote emphatically about Graham and championed the discipline in lectures at the New School.

At Bennington, Graham began to choreograph dances that explicitly engaged political themes and American history. Though Graham did not use her choreography as an instrument for class struggle, her work in the 1930s was part of the broader moment of socially conscious dance, in which politically active dancers were performing through the Works Progress Administration, participating in Communist Party pageants, and treating dance as a weapon for revolution. Graham choreographed two dances in response to the Spanish Civil War, performed at a benefit for the International Labor Defense, and rejected the Nazis’ invitation to appear at the Berlin Olympics in 1936 (her Jewish company members would not be welcome in Germany, and her dancers organized a boycott of the games).

As the threat of fascism grew, Graham’s American work fit the bill of progressive patriotism. She incorporated texts such as the Declaration of Independence and the Gettysburg Address into the narration for American Document, a dance about American history that premiered at Bennington in 1938. Critics (including Kirstein, writing for The Nation) considered American Document exquisite. Its politics were both guilty and forward-looking, emphasizing America’s violent past while hailing its democratic promise. Later, during McCarthyism, Graham’s work took a sharp tack away from active engagement with American politics and toward the narrative pieces for which she became best known: female-led interpretations of Greek myths or historical episodes with a psychosexual timbre. Such stories embodied universal ideas and emotions: “I feel that the essence of dance is the expression of man — the landscape of his soul,” she wrote, and her dances demonstrated “some wonderful thing a human being can be.” In these dances, Graham became an archetype, like the characters she inhabited; she was Clytemnestra, Medea, Jocasta. Even as she retreated from explicitly social themes, her work retained a radical tone by staging women’s sexuality. A patient of Jungian psychoanalysis, Graham was alert to the sexual repression that defined the human experience. Her Greek dances oozed sex, and she would often tell her dancers to move from their vaginas (men, she said, suffered “vagina envy”). In Night Journey, from 1947, Graham cast herself as Jocasta, Oedipus’s mother-wife, opposite her own (much younger) husband Erick Hawkins. As Jocasta and Oedipus go to bed, Graham’s Jocasta is visibly perturbed by the slippage between erotic embrace and mothering gesture. Whereas Sophocles’s myth ignores Jocasta’s perspective, Graham’s choreography foregrounds her experiences.

By then, Graham was in her fifties; her mobility was reduced, and she was no longer able to jump or kick as high as she once had. Still, she persisted as a dramatic female lead through the 1950s and ’60s, until she retired in 1970, at 76 years old, unique in a field in which most quit in their thirties. Graham remained a highly respected artist in her later years, even serving as a cultural ambassador on Cold War tours beginning in 1955. That her name was “synonymous with American modern dance,” according to the State Department, may explain why Kirstein thought it would be advantageous for Balanchine to collaborate with her on Episodes.

In the years after that joint work, Graham tumbled downward, lurching into alcoholism and refusing to leave the stage even as critics and sponsors begged her to stop performing. She remained significant, but more as a historical figure than a relevant player on the dance scene. Kirstein, once Graham’s friend, contributed to her demotion: when Lincoln Center was in development, he made sure that other dance companies, including Graham’s, would be excluded from the complex. In 1964, NYCB moved into the new $19.3 million New York State Theater at Lincoln Center, a physical representation of the institution NYCB had become, designed to Balanchine’s tastes: the pit was built to fit a full symphony orchestra, and the floors made springy to accommodate pointe shoes and leaps. Meanwhile, Graham’s company wobbled, only able to afford brief seasons in New York. A loan (never repaid) from a loyal supporter who took over the organization’s board saved the company from total collapse.

When Graham died in 1991, she had been reduced to little more than a caricature. She refused to film most of her choreography or pass down roles to other dancers; after she stopped performing in a work, it was rarely revived, and no companies besides her own were allowed to stage her pieces. She destroyed correspondence, records, and notes; as Agnes de Mille, Graham’s longtime confidante, wrote, “Martha always wanted to leave behind a legend, not a biography.” She refused to give her remaining personal materials to the New York Public Library’s dance collection because she did not want people “snickering over me after I am dead.”

Her dances became the property of one man, Ron Protas, who was Graham’s companion at the end of her life. Controlling and prickly but lacking talent and authority, Protas isolated her from longtime friends and helpers. Though he was not a trained dancer, he became the artistic director of her company, trademarked “Martha Graham” and “Martha Graham Technique,” and did not allow anyone to perform Graham’s dances or teach her approach without his permission and supervision. Former dancers were enraged, and by 2000 had set up their own Martha Graham Center to continue teaching Graham’s work. Protas sued; after the ensuing legal battle, a court ruled that the rights belonged to the Martha Graham Center, not Protas. The company did not get back up and running until 2004.

The books that were rushed to press after Graham died added to an already-fossilized image of her as a histrionic woman, a genius with too much baggage. In Martha: The Life and Work of Martha Graham (1991), Agnes de Mille depicted her subject as “absolutely self-centered,” delusional about her ill health and substance abuse, and so obsessed with her husband that she alienated her company. Blood Memory, a memoir by Graham that was heavily edited by Protas and Jacqueline Onassis, then an editor at Doubleday, was a muddle of psychoanalytic slop and ridiculous pronouncements about the power of dance. “There are always ancestral footsteps behind me, pushing me, when I am creating a new dance, and gestures are flowing through me,” rambles Graham, launching into a list of inspirations from “American Indians” to Edgard Varèse. By the mid-1990s, Graham had become a drag persona of the performer Richard Move, whose uncanny reenactment of Graham took on an outsized role in her memorialization.

Meanwhile, as Balanchine aged, the NYCB kept churning, its school training subsequent generations and regenerating the company year after year. Former dancers staged his choreography across Europe and America. The many affiliate companies that had benefited from the 1963 Ford grant continued to program Balanchine’s works and train students in his technique. He was no longer a man but an institution, a metonym for a dance tradition that reached across the entire country.

Towards the end of Balanchine’s life and in the wake of his death in 1983, many of his dancers began to write and publish memoirs that emphasized his genius — and his dancers’ total submission to his power and vision. Toni Bentley, a former NYCB dancer who has made a career out of writing about Balanchine, said in her 1982 memoir that Balanchine “knows all, sees all, and controls all.” She added, “His power over us is unique.” Such devotional worship had a dark side: dancers put up with Balanchine’s sexual harassment and pressure to stay thin. He pursued female dancers in ways that made them uncomfortable, pressured some to marry him, talked about sex publicly, and cracked dirty jokes backstage and in the classroom. (“What’s the difference between a circus performer and a ballet dancer? Circus performers have cunning stunts, and ballet dancers have stunning cunts.”) “Too fat, dear” was a common refrain used by Balanchine to justify casting decisions, and he even pinned a notice to the company board that read “BEFORE YOU GET YOUR PAY — YOU MUST WEIGH.” Still, his dancers could not help succumbing to his charismatic pull. Try as he might to resist, the dancer John Clifford recounted in his 2021 memoir, he “became a Balanchine fanatic.” There was, he wrote, a “sense of awe and hero worship surrounding Balanchine at his school.”

Over the decades, a PBS documentary, poetic eulogies, a book of Balanchine-isms, a collection of oral histories, and several biographies contributed to his deification. In a 1984 tribute for The New York Review of Books, Kirstein described Balanchine’s dances as “icons for the laity” and his dancers as “earthly angels.” Robert Gottlieb began his 2004 biography, “As Twyla Tharp has put it, ‘Balanchine is God.’” By far the most significant factor in preserving Balanchine’s legacy was the creation of the Balanchine Trust in 1987. In his will, which he only agreed to write because he feared his work would revert to his brother, and thus the Soviet state, he bequeathed various ballets to individuals. The trust, set up by Barbara Horgan, a former NYCB administrator as well as Balanchine’s personal assistant and the executor of his will, holds the ballets and doles out incomes from their productions. Former Balanchine dancers serve as repetiteurs, traveling to companies who contracted Balanchine choreography from the trust, coaching new dancers, and making sure the productions are up to par. Balanchine’s technique was also upheld through the George Balanchine Foundation’s video archives, which show young dancers learning choreography from original cast members, who recount Balanchine’s instructions and critiques. Choreography by George Balanchine: A Catalogue of Works, first published in 1983, provided essential information for the preservation of his choreography. The trust has kept Balanchine’s works alive on stages around the world, spreading them far beyond their original footprints. Today, ballet companies both small and large still rely on Balanchine’s name to bolster their repertories and draw audiences.

For more than a decade, Jennifer Homans’s scholarship has contributed to the hagiographic, triumphalist narrative in which Balanchine is the beginning, middle, and end of American ballet. Homans does not hide the fact that she is a Balanchine loyalist: she trained at the School of American Ballet, NYCB’s feeder school, and performed professionally with the Pacific Northwest Ballet, a company directed by NYCB alumni. Her first book, Apollo’s Angels: A History of Ballet (2010), argues that Balanchine represents the pinnacle of ballet’s history. “In the years following Balanchine’s death,” Homans wrote, “classical ballet, which had achieved so much in the course of the twentieth century, entered a slow decline.” In Mr. B: George Balanchine’s 20th Century (2022), Homans points out the mythology surrounding “Mr. B” and gleefully accepts the premise, constructing a portrait of Balanchine as a spiritual, otherworldly presence worth suffering for: Balanchine was “quietly building a village of angels and erecting a music-filled monument to faith and unreason, to body and beauty.” Dancers, she writes, “surrendered” themselves to Mr. B in exchange for the chance to perform his choreography. Even as Homans acknowledges his inappropriate conduct toward women, she tries to wrestle it into his genius. His irrepressible appetites become part of his project: “The whole premise of the NYCB was that Balanchine’s love of women,” she argues, “promised to give them to their best possible selves in dancing, a seduction few refused.” Homans depicts Balanchine as a thinker, and dance as an intellectual activity. She connects Balanchine’s religious beliefs, literary and philosophical interests, and political convictions to his choreography. Balanchine relied on Spinoza, for example, in introducing mathematical forms into his pieces and attempting to displace the mind-body split.

In constructing a lush portrait of Balanchine’s mind, Homans breezes through the many ways in which the man was built up into the deity she describes. Even as she devotes space to Kirstein, explaining his fastidious support, generous checkbook, and fundraising powers, she ultimately portrays Balanchine as the chief architect of NYCB. Names like Morton Baum, Nelson Rockefeller, W. McNeil Lowry, and John D. Rockefeller III, all of whom provided funding for Balanchine, as well as the NYCB theaters that allowed for his rise, receive brief mention. In Mr. B, NYCB’s institutional history serves as a prelude for an exploration of Balanchine’s inner life. Too often, Homans also presents her interlocutors as impartial parties instead of active participants in shaping his reputation and legacy. We are fed quotations from Edwin Denby, one of Balanchine’s most articulate champions, but are not told just how important it was that there was a critic inventing language to explain that Balanchine was the most important American choreographer. Horgan, Balanchine’s assistant-turned-executor, who had not told all to any scholar until Homans, is described as “the head of a new priesthood, dedicated to guarding the Balanchine flame.” But the trust itself appears as a neutral actor, simply keeping Balanchine ballets in rotation, and Horgan is treated as an unbiased source. Footnotes to Mr. B reveal countless interviews with Horgan, whose insider’s perspective is peppered throughout the book. Yet we never learn just how influential Horgan has been at shaping the Balanchine myth through her work at the trust and foundation.

It is easier for Graham biographers to avoid the deification of their subject because there is less pressure to hold her up as the ultimate American dancer and choreographer. In the introduction to Martha Graham: When Dance Became Modern (2022), the scholar Neil Baldwin promises to deliver an explanation of how “Martha Graham became Martha Graham.” Throughout the book, though, he largely reproduces Graham’s epic vision of herself, writing that “when Martha Graham gazed upon mythic antiquity, contracted the core of her body, and, like the pioneers, ventured outward toward unknown spaces, dance became modern.” The myth of Martha Graham came more from herself than from acolytes; she was the author of her own “Marthology,” as the critic Marcia B. Siegel has described it. Yet Baldwin gets caught up in Graham’s charisma instead of putting forth an argument about how her legend was shaped in the first place.

A career biographer — his previous subjects include Man Ray, Thomas Edison, and William Carlos Williams — Baldwin lacks the knowledge about the ecosystem of modern dance that is essential to understanding how Graham rose and fell over the course of her career. Graham’s manager Frances Hawkins, who was instrumental in booking her early performances, is absent from Baldwin’s book, as is any explanation of the modern dance touring industry, the main way companies earned income and disseminated their art. Nor does Baldwin elucidate how the summer residencies at Bennington College provided income and institutional support, grew audiences, and shaped the field. In Baldwin’s narrative, the radical social and political context of modern dance in the 1930s falls away in favor of a bland reading of Graham’s work as “American,” reflecting nationalist promises of democracy. Baldwin concludes his tale in 1950, condensing the last forty years of Graham’s life into a seven-page epilogue.

A dance critic and scholar, Deborah Jowitt is familiar with the history and topology of modern dance and is more successful than Homans or Baldwin at diagnosing its structural forces. Errand into the Maze: The Life and Works of Martha Graham depicts the modern dance touring circuit, Graham’s transition from vaudeville to high art and the financial consequences of that move, her lover and accompanist Louis Horst’s indispensable support of her career, and how the Bennington School created “endless chains of pupils turned teachers in order to teach more pupils to be teachers.” But Jowitt, too, rushes through Graham’s late career, a chapter without which any story of Graham is incomplete. Errand into the Maze contains no mention of Graham’s dwindling prominence and capacity, and in fact characterizes the choreographer in the midst of her alcoholism as an “unstoppable” artist. Jowitt does not explain that Graham survived in her later career thanks to money from longtime ally Francis Mason, who also facilitated her Cold War tours. Protas’s takeover of Graham’s work and her legacy is also missing from Jowitt’s telling.

By overlooking and deemphasizing the ways in which dance is created beyond an individual choreographer’s talent, all three of these biographies reproduce a tendency in dance history to position dance outside the market. Homans’s biography most explicitly portrays the realm of Balanchine as a utopian community, a “world of the spirit, an alternate vision of the twentieth century.” But Baldwin and Jowitt, too, are guilty of seeing dance as largely personality-based. The image of Graham that grounds Baldwin’s story is of her “luminous half-closed eyes fixed downward and focused inward, seeking an undefined, urgent answer.” Jowitt’s story finishes with a depiction of Graham as a horse, singularly focused on her craft: “How she raced toward it! How she leapt to bring it to life!” The reticence to talk about dance as a product of enterprise exists in part because it is the least profitable art form; to run a dance company in America, where public arts subsidies are meant to serve as a catalyst for private funding, is to be in a constant state of fiscal crisis. Cinema has Hollywood and the streaming monopolies, painting the art market, but dance remains on the outskirts of the culture industry, the theater and studio seen as sacred spaces in which art is untouched by economic forces. Dance is considered a labor of love, something from which no one will ever make real money, and thus a sacrificial service. The beauty and spiritual meaning of bodies in motion transcends material needs, and dance becomes a detached, idealistic phenomenon, the product of creative magic instead of labor and industry.

Today, if a young person wants to take a dance class in America, they usually sign up for ballet. Perhaps they saw Balanchine’s The Nutcracker. Or maybe they were influenced by the baby-pink onslaught of balletcore, featuring ethereal NYCB dancers in ad campaigns for brands like Reformation, J. Crew, and Zara. It is likely that their teacher will have a connection to Balanchine: maybe the instructor studied at the School of American Ballet one summer, maybe their training lineage connects back to a famous NYCB ballerina, or maybe they themselves danced with one of the many regional companies run by former Balanchine dancers. As a young dancer in the Seattle suburbs, I learned ballet from teachers who had connections to the Pacific Northwest Ballet, led by Balanchine alumni and a former NYCB dancer. In my strip-mall studio sandwiched between a Subway and a computer repair shop, I saw how Balanchine dancers held their hands, prepared for a pirouette, and over-crossed their fifth positions. Balanchine is baked into American ballet.

Modern dance is not available in the same way. Graham’s repertory and technique are offered at the Martha Graham Dance Center, a studio or two in New York, and a few colleges, where both Graham and her dances have mostly been relegated to dance history syllabi. Students of modern dance are much more likely to encounter Trisha Brown or Yvonne Rainer as a touchstone in their training than Graham.

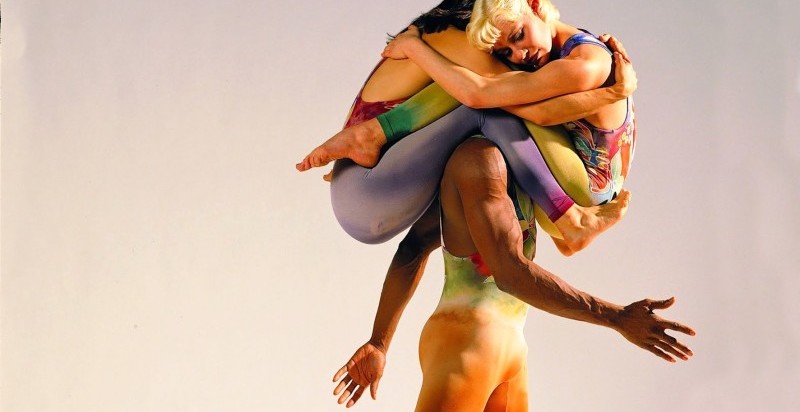

The landscape of dance training in America affects what we see on stage. Balanchine’s choreography is available year-round in cities across the country, while the Graham company — even during its centennial celebration — performs in short stints at a handful of universities, some performing arts centers, and a few international stops, given less than a week at City Center in New York. Stylistically, too, the dominance of Balanchine has shaped how young dancers and choreographers move. A ballet base punctuated with angular patterns and swizzling legs, puzzle-like partnering, and rhythmic patterns populate contemporary ballet work, and even modern dance choreographers quote or interpolate iconic Balanchine moments, like the famous pose from Agon in which the female dancer wraps her leg around her male partner as he catches her in a split. In the world of modern dance, Graham’s dramatic choreography and expressive gestures have fallen out of style. Her students and former dancers, including José Limón, Merce Cunningham, and Paul Taylor, moved modern dance in new directions, elevating the status of men and rebelling against Graham’s reliance on narrative. Their students, such as Brown, Rainer, Simone Forti, and Lucinda Childs, developed what is known as postmodern dance, which deconstructed the form to its most basic parts, like running and walking, sitting down and standing up. And students of postmodernism concluded the twentieth century by rejecting minimalism and reintroducing athleticism and narrative. Mother Martha has been succeeded by her offspring. Meanwhile, no son (prominent ballet choreographers are predominantly male) has surpassed father Balanchine’s influence.

Contrary to what the state of American dance suggests, Graham’s work today feels much more contemporary and relevant than Balanchine’s. (Since 1959 when Episodes premiered, the roles have reversed once again.) Her choreographies transport us back to a time when art and political life were closer together, and processing current events through movement felt imperative. In comparison, Balanchine’s rejection of politics and vulgar patriotism sometimes feel trite and outdated. Even Graham’s later work, overly theatrical and devoid of explicit political meaning, offers a way of thinking through grief and failure. Graham made a real effort to communicate with movement, to show the body as an instrument with which one can process a particular moment in time.

Graham can even serve as a feminist counterpoint to Balanchine’s legacy of misogyny, sexual misconduct, and expectations of extreme thinness. Her dances feature female leads who have appetites, act on them, and deal with the consequences. Her women are monstrous, ruthless. A female Graham dancer has strong legs and a rippling torso; she moves with groundedness and athleticism, offering an exhilarating emotional performance. Even while partnered by a man, she conveys a certain dominance and autonomy. If he dropped his hand, she would still stand. The same cannot be said of a Balanchine ballerina.

What would American dance look like if, instead of strapping on pointe shoes and toiling over exercises at the barre, young dancers were encouraged to take up modern dance? Ballet and modern share many technical similarities — the pointed feet, the flexibility for kicks and jumps — but there is a fundamental difference in ethos between the two disciplines. While ballet remains out of reach for many, with its strict requirements of physical ability, modern dance is more participatory. We can thank Graham for its core principle: that the body is a medium through which we can transmit emotions and ideas. If modern dance reigned, perhaps movement would be better integrated into our lives. Instead of something we consume as audience members, dance would become equipment for living.

Walking Creature. Copyright © John Kane / Silver Sun Studio. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Walking Creature. Copyright © John Kane / Silver Sun Studio. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Position to Celebrate. Copyright © John Kane / Silver Sun Studio. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Position to Celebrate. Copyright © John Kane / Silver Sun Studio. All rights reserved. Used by permission.