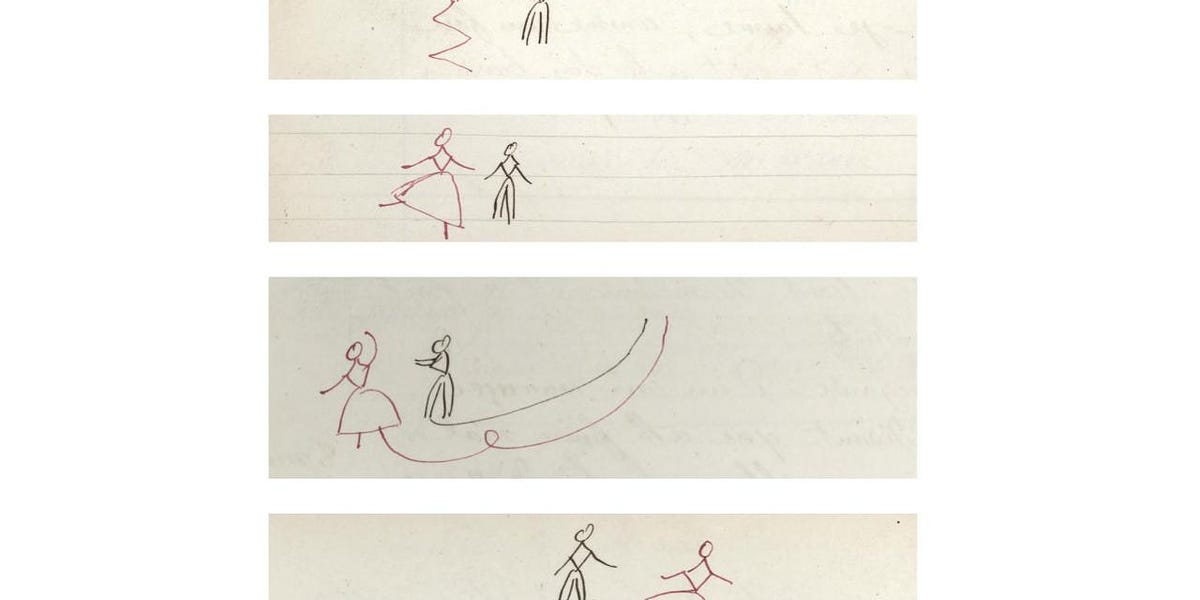

An image from “Five Ballets from Paris and St. Petersburg.” Six drawings from Act One, No. 6, of Henri Justamant’s staging manual for Paquita, circa 1854. Theaterwissenschaftliche Sammlung der Universität Köln, Schloß Wahn, Inventory Number 70- 479, pages 16– 19.

At 856 pages and 3.4 pounds, Doug Fullington and Marian Smith’s new book, Five Ballets from Paris and St. Petersburg—Giselle, Paquita, Le Corsaire, La Bayadère, Raymonda (Oxford, July 2024) is an impressive tome. And it is even more so once one begins to add up the long list of archival sources its two authors corralled, deciphered, and analyzed, a list that includes musical scores, violin reductions created for rehearsals (known as répétiteurs), two different systems of dance notations (Stepanov Notation, developed in Russia, and Justamant notation, created in France), choreographic drawings, librettos, program books, posters, period reviews, first-person reminiscences, and more. Each of the five ballets in question is analyzed with amazing thoroughness, tracing themes and details from one source to the next, and by so doing creating a kind of 360 degree immersive portrait. By the time you’re finished reading about each of the ballets discussed, you feel like you know everything you could possibly know about it. In fact, you can almost see and hear that ballet as it was performed in Romantic-era Paris or pre-revolutionary St. Petersburg.

But there is more to Five Ballets than maniacal thoroughness. The book is also a wonderfully engaging read. Fullington and Smith have shaped this Mont Blanc of minutiae into a narrative that keeps you happily engrossed, consuming detail after detail as if they were pleasurable bonbons. They have also made a valiant effort to convey why people enjoyed these ballets and found them exciting and entertaining in the first place. With all the serious discussions being had around cultural insensitivity, exoticization and the fetishization of female characters, the question inevitably arises: Why even bother with these works. Well, as Marian Smith put it recently, when you peel away layers of cliché and coarseness accrued over the course of the twentieth century, you often find works that are full of variety, contrasting dance styles, storytelling, humor, and relatable, appealing characters. You can also distinguish the good from the bad. These ballets were meant to keep people engaged, entertained, and moved. It is worth looking at them a little bit more closely, figuring out what made them tick, and perhaps drawing a few lessons from them.

Marian Smith and Doug Fullington in Seattle

Smith is a professor emerita of music at the University of Oregon, the author of Ballet and Opera in the Age of Giselle, and editor of La Sylphide: Paris 1832 and Beyond. Fullington is a musicologist and dance historian who for several years was also Audience Education Manager at Pacific Northwest Ballet. And he is one of the foremost experts in choreographic notation, one of a small number of people in the world who know how to decipher Stepanov Notation, a system developed by the dancer Vladimir Ivanovich Stepanov at the Imperial Theaters in St. Petersburg in the late nineteenth century and subsequently used to notate dozens of ballets in the company’s repertory. Both Smith and Fullington have consulted in the staging of nineteenth-century works, including Giselle at Pacific Northwest Ballet and Paquita at the Bavarian State Ballet in 2014. Currently, Fullington is collaborating with Peter Boal on a historically-informed production of The Sleeping Beauty at Pacific Northwest Ballet that will open in 2025. (He also recently took part in a staging of La Bayadère set in the Far West at Indiana University.)

Long story short, the book, which took Smith and Fullington five years to complete, was a massive undertaking. But what has emerged is anything but heavy—it reflects the two author’s understanding of and delight in the materials they have discovered and worked with. As Smith put it to me recently, “It’s what we do for love.”

The three of us spoke recently via Zoom; Fullington was in Seattle, Smith in Eugene, Oregon.

Congrats on the publication of Five Ballets from Paris and St. Petersburg. What a sense of accomplishment you must have. So, tell me, why this book now?

Marian: Well, one thing is that we found out about a trove of notations scores by Henri Justamant in Germany from a friend, Stephanie Schroedter, who was doing research on the opera composer Giacomo Meyerbeer at a library in Wahn, outside of Cologne. [Note: Henri Justamant was a French ballet master and choreographer who worked in Paris, Lyon, and Brussels in the mid-nineteenth century and who notated scores of ballets being performed in France at the time.] When I saw the list of scores, I just about flipped. It included Le Corsaire, and Paquita. Doug and I zoomed over there in 2015 and we just ate it up. The scores were so explicit, it was almost like seeing a video of the ballets. Doug had already done a lot of work on the Russian Stepanov notations made by Nikolai Sergeyev. We wanted everyone to know about these discoveries.

Doug: Going even further back, I was inspired by Roland John Wiley's book from 1985, Tchaikovsky’s Ballets, which my parents gave me when I was 17. That was a model for me. I tried to do something similar in an article I wrote for Ballet Review on Raymonda in 1998. And of course, Marian wrote her wonderful book on Giselle around the same time. The two of us met in 2000 at the Bournonville Festival in Copenhagen. We finally got to a point where we felt like we had sufficient information on a certain number of ballets, and we thought “Let's do something with this.”

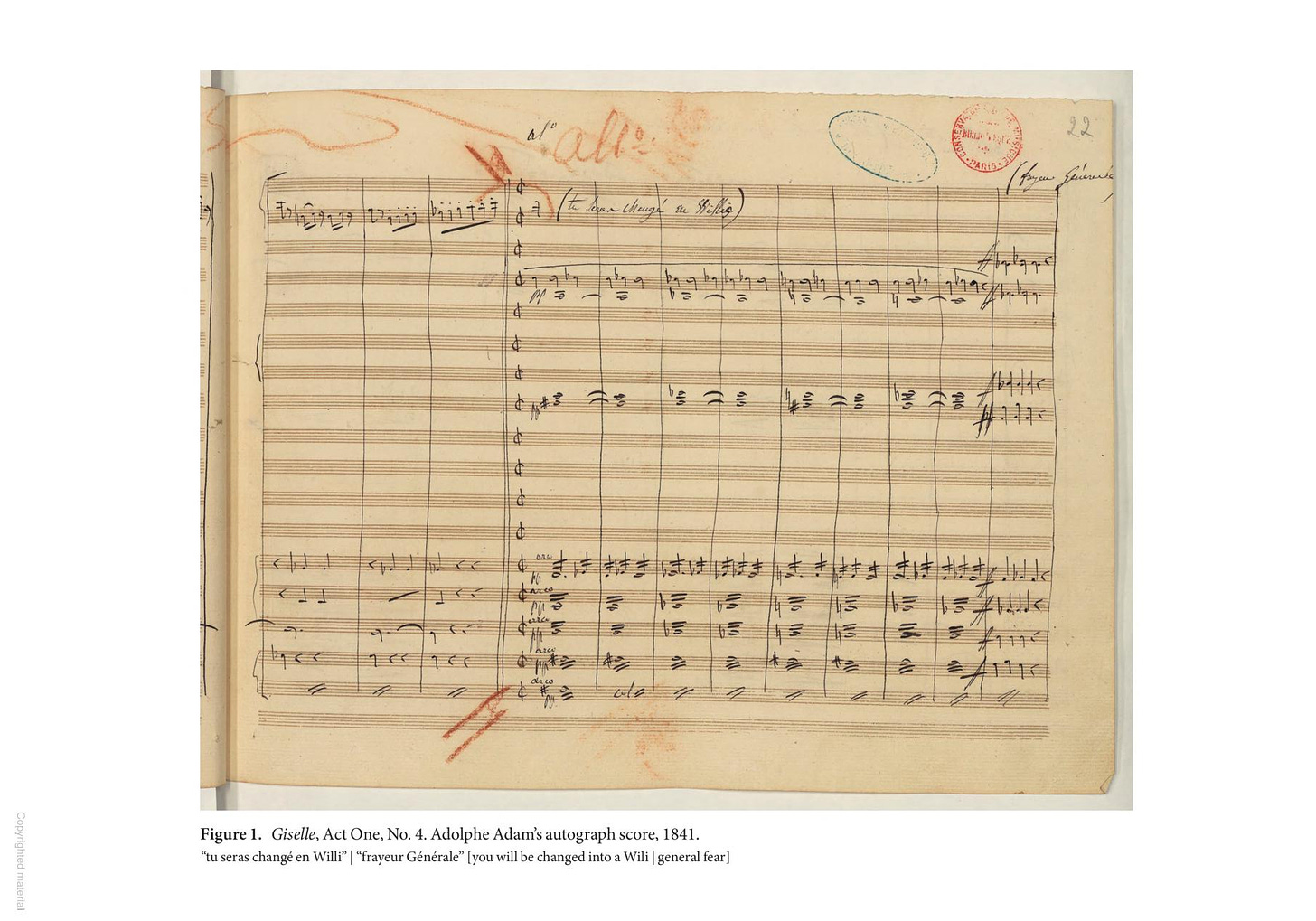

Giselle, Act One, No. 4. Adolphe Adam’s autograph score, 1841. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Département de la Musique, MS- 2644, fol. 22r.

Both of you assisted Peter Boal in his 2011 staging of Giselle for Pacific Northwest Ballet. Did you refer to the Stepanov and Justamant notations then?

Yes. Marian and I used the Justamant most particularly for the pantomime, because the Stepanov is more spare in that respect. We used a hybrid of sources.

How did the two of you combine your complementary skills in this gargantuan project?

Doug: Generally I dealt with the Russian versions of the ballets and Marian dealt with the French versions, with some overlap. We sent what we had written back and forth.

Marian: We did a lot of editing of each other's chapters.

Doug: And Marian really led the way on the analysis of musical scores. I tried to apply the same approach to what I was doing with the choreography. Marian also authored the chapter that explains why nineteenth century ballet was so popular.

Such an important chapter, especially because there is so much discussion now about these ballets and whether they are offensive and how to deal with the offensive bits. Which sometimes brings up the question, Why even keep them?

Doug: So many of the ideas around nineteenth century ballet are really based on mid-twentieth- century [Soviet] productions. Part of what we wanted to do was set that aside and really look at what the ballets were like when they were first created.

15-16. Costume drawings by Henri d’Orschwiller depicting Georges Elie as Inigo and Carlotta Grisi as Paquita, Act One. Pencil, watercolor, 1846. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Bibliothèque Musée de l’Opèra, D216- 15 (80– 91). 17. Caroline Lassia in the Pas des manteaux from Paquita. Lithograph published by Martinet, Galerie Dramatique, 1846. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Bibliothèque Musée de l’Opéra, C- 261 (19,267). 18. Costume drawing (unsigned) depicting Hussards (of seven regiments) in Paquita, 1846. Pencil, watercolor. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Bibliothèque Musée de l’Opéra, D216- 15 (80– 91).

Why did you choose these five ballets?

Marian: Partly because they’re all in repertory in some form, and people know them. There are so many other ballets that aren't in repertory, and those are fascinating, but we don't have a way get a sense of them. With these, it’s easier for us to conceptualize what the originals were like.

Why not Coppélia or The Little Humpbacked Horse, or Nutcracker…

Doug: Some of it comes down to the practical question of having what we felt were sufficient sources. And personal interests too. I love Raymonda, and the score, by Glazunov. And with La Bayadère, it's just so well notated. Corsaire is, I think, deeply misunderstood because it has been changed so much. And we had worked on Paquita and Giselle, so there was a practical side to it as well.

Marian: We were also really interested in finding a through line between France and Russia—French ballets that lived on in Russia.

I'm curious with these more exotic ballets, like Le Corsaire and La Bayadère, that are usually considered the most problematic for contemporary audiences–what was your approach? What were you trying to find out about them? And did your research change the way you thought about them?

Doug: Well they’re obviously products of their day, so they represent social norms and ideologies of the time. We tried to take a neutral approach, pointing out the things that we found problematic, without offering solutions, because that wasn't the purpose of the book.

Marian: I think I did write in the Corsaire chapter that it’s so Islamophobic you couldn't possibly stage it the way it was now. But the book is less about concrete solutions than about knowing what actually happened, which itself can help lead to solutions. One thing that I found is that the character of Medora is supposedly Jewish. [According to the libretto.] She’s the heroine, she's admirable, and she's beautiful—all good things.

Why do you think these exotic subjects were so popular, both with creators and with the audience? Is it partly because people couldn’t travel places, so this was the next best thing?

Marian: I think that’s part of it. In Paris, in addition to ballets and operas set in exotic locations, there were panorama theaters where paintings and representations of exotic settings were displayed, and they were very popular. The appetite for exoticism was apparently insatiable. And it was being whetted by France’s imperial incursions and the seizure of artifacts. What counted as exotic is interesting, too. Germany was exotic. Spain was exotic. Scotland. The Americas.

How did composers like Ludwig Minkus and Adolphe Adam go about depicting these far-off places musically?

Doug: If a composer wanted to compose a mazurka or czardas or a Spanish dance, that musical language was accessible. They knew what those dances were supposed to sound like. But for a ballet like La Bayadère, set in India, there was a lot of guesswork. Minkus only tried a couple of times for a few bars to create an “Indian” sound. He would use harmonies that he wouldn't use in common practice, extending the harmonic and melodic language. He drew on norms developed by other European composers who were writing exotic works, particularly in the French opera.

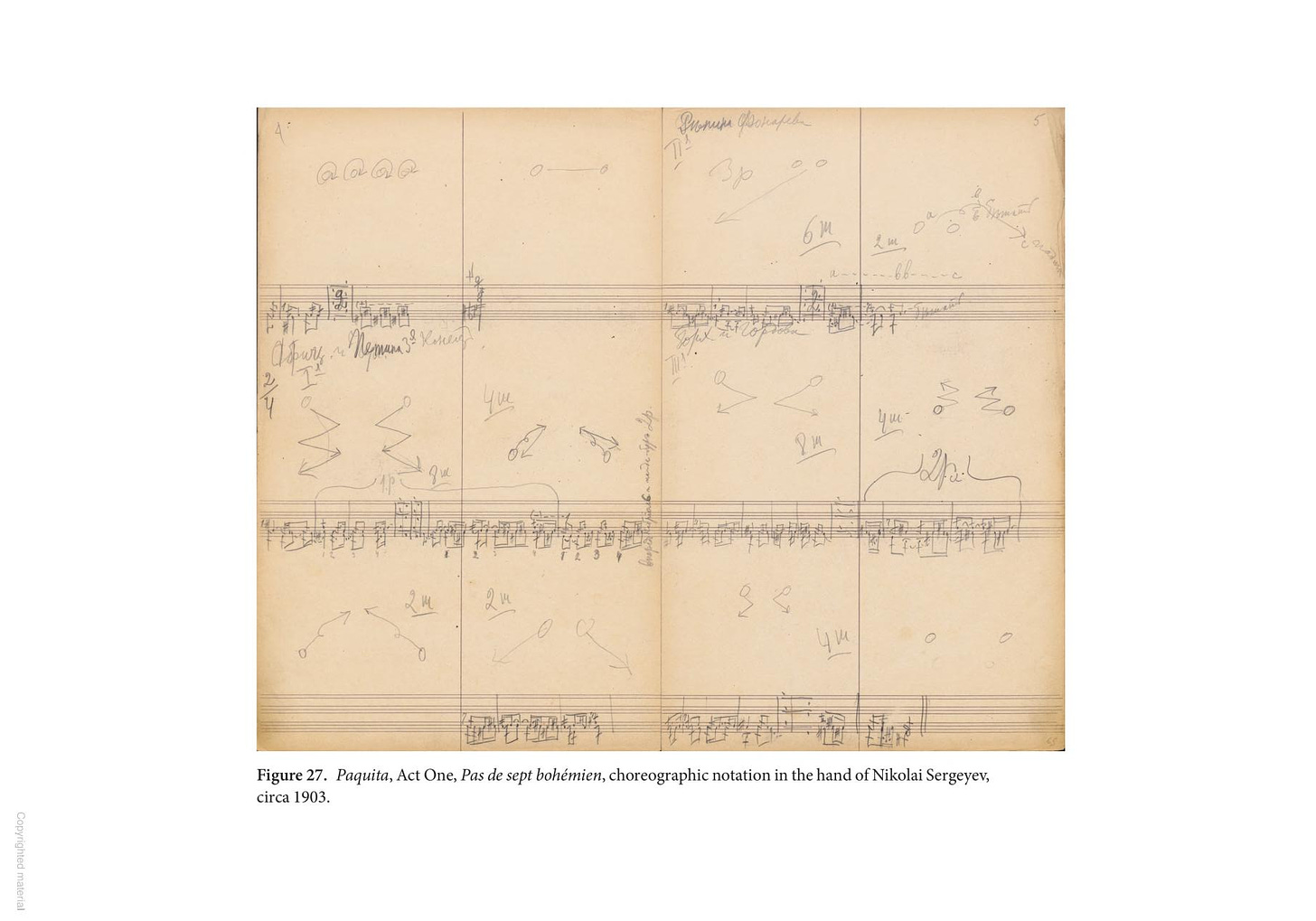

Paquita, Act One, Pas de sept bohémien, pages 4–5, choreographic notation in the hand of Nikolai Sergeyev, circa 1903. MS Thr 245 (28), Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

What are the different strengths of the composers you encountered, like Adolph Adam (Giselle and Le Corsaire), Édouard Deldevez (Paquita), Ludwig Minkus (La Bayadère), and Alexander Glazunov (Raymonda)?

Marian: I just love Adolphe Adam—everyone who studies him loves him. I think the Giselle score is brilliant. He was a man of the theater, and he knew exactly what his job was. It’s not just that he was practical, which he was, but he was so full of ideas, and great with atmosphere. And the Corsaire score—some of it is just hilarious. There’s a lot of pirate music, some of which sounds like Gilbert and Sullivan. He writes a fugue in which the subject is the first four notes of a pirate song, so he’s mixing something humorous and rough and crazy with a very sophisticated German genre. It’s a hoot!

What is it that separates these scores from the “great” ballet scores by Tchaikovsky and Délibes?

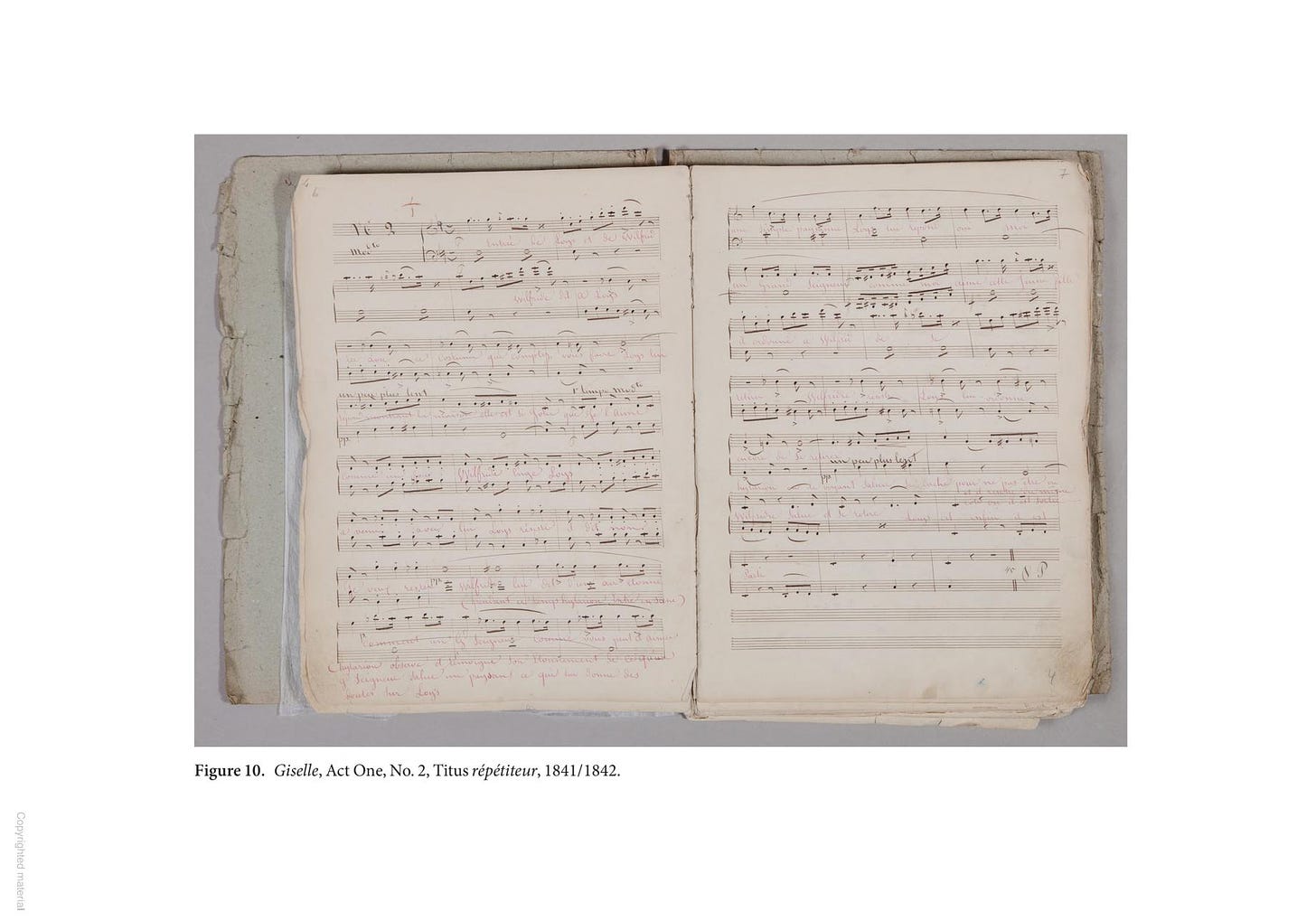

Marian: The earlier scores were more directly tied to the action. They were attentive to every move. You can almost picture the composers right there, responding to what the dancers are doing. Later, the music becomes more big-picture, and can stand on its own.

You write about “parlante” music, or “speaking” music, in these ballets, which is an idea that I love. What are the characteristics of this kind of music?

Marian: It’s almost like a recitative in opera. It doesn’t have a clear pulse all the time. It’s following what sounds like speech. Sometimes, it even sounds like a voice, or like instruments imitating a voice. It can also echo the melody of a song in a way that brings the words to your mind. I think the audience was so tuned into these melodies that they could actually hear the words.

You’ve drawn from an impressive assortment of sources: musical scores, répétiteurs, Stepanov notations, Justamant notations, libretti, program books, drawings by Pavel Gert, reminiscences. How did you get your arms around all of this material?

Doug: I think that's the value of two people working on a project—you can apply different kinds of expertise. I also had help. Kyle Davis, a dancer at Pacific Northwest Ballet, helped me figure out how to refer to certain steps, the order of the French terms in a combination, that sort of thing. We had many Zooms during Covid. And Andrew Foster, the ballet historian in London. I would send him the production performance histories, because he knows so much about Russian casting. Between Marian and me, and the assistance we received from other people, we were able to really make use of the sources. People were helpful and generous and just really, really nice.

Marian: I had a lot help from Lisa Arkin, a close friend of mine who is a character dancer and also a great mime. She acted out some of the passages in Giselle and we talked through the characters. It was extremely helpful.

How did you go about locating and accessing all of the resources? Where were they? And how hard was it to deal with the Russian archives in the context of the war?

Doug: I was lucky to get everything I needed from the museums and archives in St. Petersburg and Moscow before the war started. I worked closely with archivists at the Bakhrushin Museum and the Theater Museum in St. Petersburg. Once the war began, they very sweetly said, congratulations to you and Marian, we’re so sorry but we’re not allowed to work with you. Alexei Ratmansky made a few things available to me that he had. Lynn Garafola provided some programs. Marian and I went to Cologne together, and we went to Sandra Noll Hammond’s beach cabin in Santa Rosa California—Sandra is a nineteenth-century ballet expert and worked with us on the Justamant scores. Gallica, the portal of the French Bibliothèque Nationale is a great resource. We had the catalogue from Wahn for the Justamant notations. We knew about the Sergeyev collection at Harvard. All of that is digitized now. We would write to archives and ask, Do you have this thing we’re looking for?

Giselle, Act One, No. 2, Titus répétiteur, 1841/ 1842. St. Petersburg State Museum of Theatre and Music, GIK 7114/ 8a, pages 6– 7.

Do you think there are more materials out there that you haven’t yet had a chance to see?

Doug: I do think sources will continue to be found. There has to be a Corsaire répétiteur somewhere at the Paris Opera. It’s listed in the nineteenth century catalogue, so it has probably been misfiled somewhere.

Marian: The répétiteurs were bought and sold because people were using them in the rehearsal studio. So there are probably a lot still in private collections.

In your view, what is the advantage of this 360-degree approach?

Marian: It helps you to see and hear the ballet better. You find out what it must have been like in the theater.

How are the Justamant notations different from Sergeyev’s, written in Stepanov notation?

Doug: With Sergeyev, once you get past Bayadère, for which he made a very clear copy and worked off of a rough draft, the rest of the notations seem like he was writing down what he was seeing in the studio, as an observer. For example when he describes the mad scene in Giselle, he wrote down what Pavlova was doing with her hand, rather than saying what it meant. You get the idea of him perhaps not being completely inside in the creative process, even though he was acting as a ballet master. But Justamant created manuals for restaging, with a lot of practical information, like lighting instructions, and a list of properties. Very functional.

What sense of Justamant do you get from the notes?

Doug: He must have been a real character. There are dozens and dozens of manuscripts, and they are so meticulous. He notated everything, from academic classics to light works. There is even a ballet on roller skates in there.

Why did he notate everything?

Marian: I think some of it he did for his own use. We couldn't say this outright in the book, because we couldn't prove it, but I bet that, for example, he would see Corsaire in Paris, write it down, bring it down to Lyon and stage it there, and then he could restage it somewhere else, as he did with Giselle. He also made presentation copies. My colleague Helena Spencer actually found one online and bought it from an auction house. But also, who knows, maybe he just enjoyed doing it. He had a little place near the Bois de Boulogne where he would sit with his black ink and his red ink. His friends would come over and see him making these manuscripts. I think he was obsessed. He loved writing these things down. I’ve wondered what it would be like to meet him and to tell him what we've done.

And Sergeyev?

Doug: I think he had a frustrating career. There was all the upheaval and turmoil in Russia in the first couple of decades of the of the twentieth century. He really latched on to the notation system. He seemed to love the repertory and be very proud of the Imperial Ballet and the fact that he was associated with it. But I think he was overwhelmed once Alexander Gorsky left in 1900, because he had to ask for two assistants to keep the notation work going. After the Bolshevik Revolution, he wanted to direct the former Imperial Theater and was turned down. He wrote to Paris Opera about staging and directing there, and was, on the whole, turned down. He wanted everybody to do the Shades scene from Bayadère, and theaters kept saying, you're past your sell-by date. He was working in a time of change that wasn't so interested in what he had to offer. I think it was frustrating working with Ninette De Valois in London, because she would make changes to what he did.

Why do you think both the Justamant and Sergeyev notations were forgotten and ignored for so long? I mean they weren’t really rediscovered until the seventies when Wiley wrote about them, and were hardly used until the Sergei Vikharev Sleeping Beauty reconstruction in St. Petersburg in 1999.

Marian: I think people wanted to remake things the way they wanted, because they're creative artists. And in ballet the idea of passing things down from body to body is so important.

Doug: And we went through a period where pantomime was out of fashion, and where academic dancing was seen as only that, academic. But then eventually you get to a point where you're so far away from the time when these ballets were made, and suddenly people are a little more willing to look back and see what they were really like. It’s like the early music movement: Let's see what Beethoven sounds like on the instruments Beethoven had at his disposal at the time. Let’s see what it might say to us now. But there was also a lot of distrust of Sergeyev, because of a political culture of maligning him personally and professionally. [After the Revolution, Sergeyev absconded from Russia with his trove of notations, which he used to stage ballets in the West.] What we tried to do in the introduction of the book was address his professionalism and his ability. Clearly he knew the notation system, clearly he knew the step vocabulary, and he was able to stage these ballets.

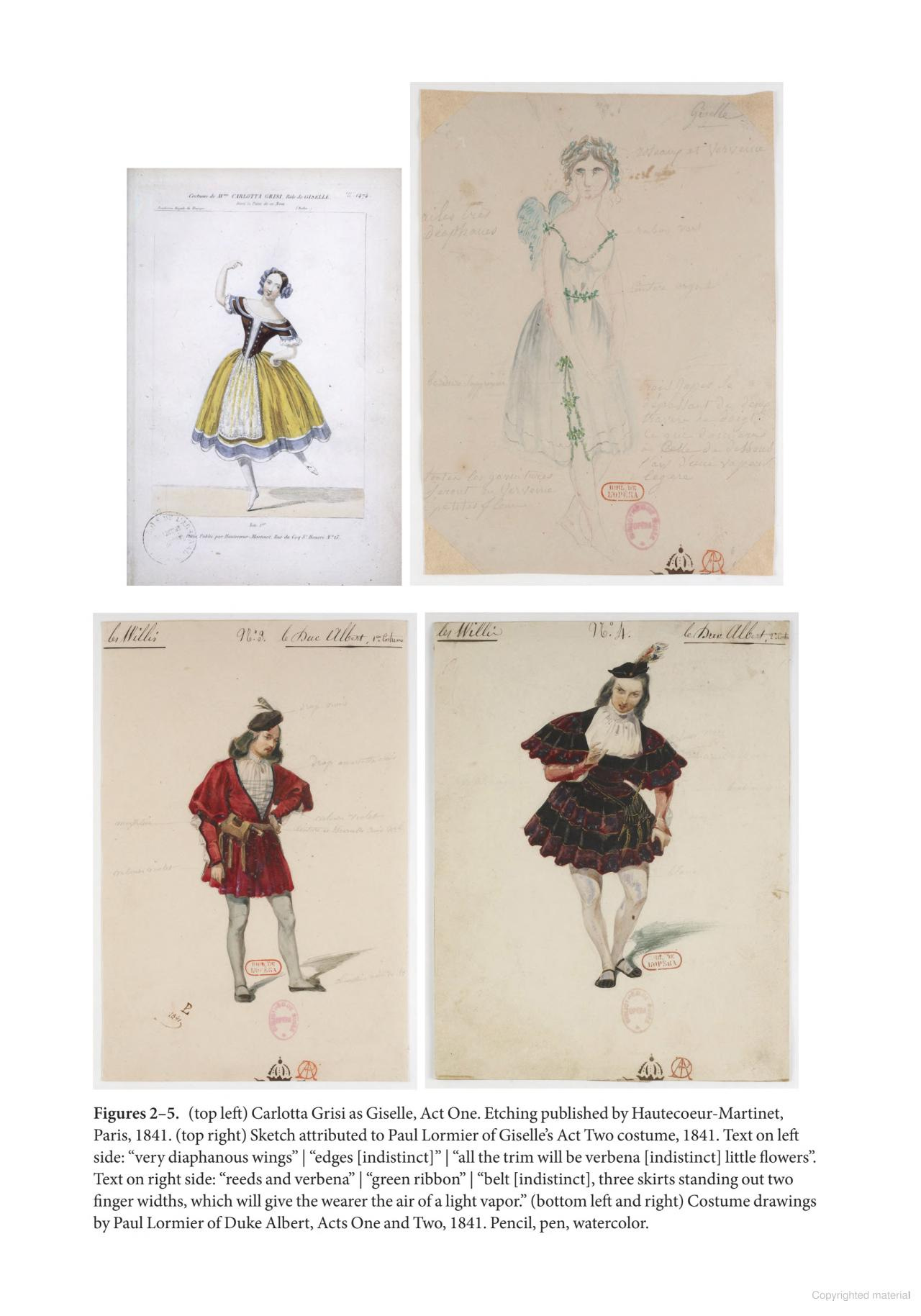

2. Carlotta Grisi as Giselle, Act One. Etching published by Hautecoeur- Martinet, Paris, 1841. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Bibliothèque Musée de l’Opéra, BMO C- 261 (15- 1474). 3. Sketch of Giselle’s Act Two costume attributed to Paul Lormier, 1841. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Bibliothèque Musée de l’Opéra, D216- 13 (81). 4– 5. Costume drawings by Paul Lormier of Duke Albert, Acts One and Two, 1841. Pencil, pen, watercolor. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Bibliothèque Musée de l’Opéra, D216- 13 (77– 78).

Maybe he was just not the most inspired stager—could that be it? And perhaps that led to distrust of the value of the information in the notes.

Doug: Definitely. Some accounts suggest that he didn't have that creative, inspirational spark. And in the West, he suffered a language barrier. Maybe he got frustrated easily. But also, today’s ballet industry seems largely wedded to mid-twentieth century versions, and when something diverges from that, people say either “We don’t do that” or “That’s not what it is.” There’s a narrowness in classical ballet regarding what kind of step vocabulary and combinations are acceptable. The notations ask you to have a more open mind about the elements that make up classical ballet.

Marian: A lot of people who are trained classically today are only trained in ballet steps, not character steps, and not even mime so much. And I think one of the keys to the success of the 19th century ballets was that they did have a wide vocabulary of steps, and it wasn't all classical. That has been lost.

In the book, you take issue with some of Nadine Meisner’s assertions about Marius Petipa in her 2019 biography. What do you think she gets wrong about Petipa?

Doug: We think she attributes certain developments or choreography to Petipa that he didn't necessarily do early on in his years in St Petersburg. Some of the things she attributes to him were more attributable to his predecessors. Like changes in Giselle; there’s just not that much evidence that we could find that he was responsible for them. Petipa is part of a continuum of French choreographers, and just because we know far less about Perrot, Mazilier, and Titus, Petipa gets credited with a lot of things that other people probably did or did first. It’s all incremental.

So what were Petipa’s innovations, then?

Doug: One of the big ones we talk about is this development of the pas d’action from a one-movement scene that had dancing and action built into a more formal structure—a multi movement suite of dances. You can see an example of the multi-movement structure in Mazilier’s Le Corsaire: it has an opening of five variations and a coda. Petipa incorporated narrative action into this structure, as in the Rose Adagio in Sleeping Beauty. I don't find that combination of multi movement structure with narrative before Petipa.

Marian: It did exist before, but it followed the action of a particular ballet rather than having a set structure that you would fill in.

Did this also make the stage action more complex?

Doug: It did, and so did another innovation we refer to as polyphonic choreography, where there are three or more choreographic ideas going on at the same time. Petipa might have twelve men dancing one thing and twelve women dancing something different, plus six soloists dancing something else. Think of the Garland Dance in Sleeping Beauty, with its men, women, and children all dancing their own choreography. Sometimes there was also a lead dancer.

That sounds like Balanchine—like in Symphony in C! He was obviously drawing inspiration from Petipa. What about ballet technique—how did Petipa innovate there?

Doug: In the book we talk about the absorption of Italian technique in the late 1880’s and all the way through the 1890’s. You see it in the ballets he made for Pierina Legnani, in which she would repeat steps many times: 32 hops, 32 fouéttés. There are entire variations where you’re essentially hopping on one leg. We aren’t finding anything like that in Justamant. Petipa seemed to think that a lot of what the Italians were doing was distasteful, but those were the dancers he had to work with, so he incorporated their strengths.

We also write about Petipa’s curatorial approach to repertory. He kept a lot of old ballets in repertory long after they had been discarded in Paris, like Giselle. So that by the time we get into the twentieth century, they had a huge repertory in St. Petersburg, including ballets by Perrot and Mazilier as well as Petipa. He would revise the older ballets, but he also seems to have kept plenty of original elements.

What were your most surprising discoveries in the process of researching and writing this book?

Marian: I was surprised by what I read about Giselle. She was not shy. And as my friend and helper Lisa Arkin pointed out, she stood up to everybody. It was so different from what I've seen depicted so often onstage. There were some things in Le Corsaire that really surprised me. Like the outright anti-Semitism. It was like a textbook case that people could use in Jewish Studies classes or a class on the history of anti-Semitism. And it was supposed to be funny.

Doug: Mine are more choreographic. One is that the choreography notated by Justamant is definitely worth reviving, and I think it will look different from the Russian ballets. It’s more similar to August Bournonville’s choreography, which of course is rooted in French ballet. The Giselle steps are beautiful. There is a wonderful musicality and creativity. And going back to Petipa, I love the way he used steps and gestures that we would consider character dance, right in the middle of something we think of as classical.

Whom do you see as the audience for the book, and how do you hope it will be used?

Marian: The audience for the book—anyone interested in ballet, staging practices, theater, music, and ballet’s sister art, opera. and I have to say, some of the eyewitness reports about these ballets are quite fun to read. The book could be useful for anyone who might want to stage these ballets in some way, or even for creating a new ballet. A person could learn from the tenets of these ballets: variety, humor, relatability, those sorts of things.

Doug: And for the works that ballet directors are grappling with, like Bayadère and Le Corsaire, we hope it might add something to the conversation to know what they really were like. We hope artistic directors will read it. They're the ones choosing the repertory and having to determine what to put on stage.