Majorette Dancing Is For Every Body, Period.

[ad_1]

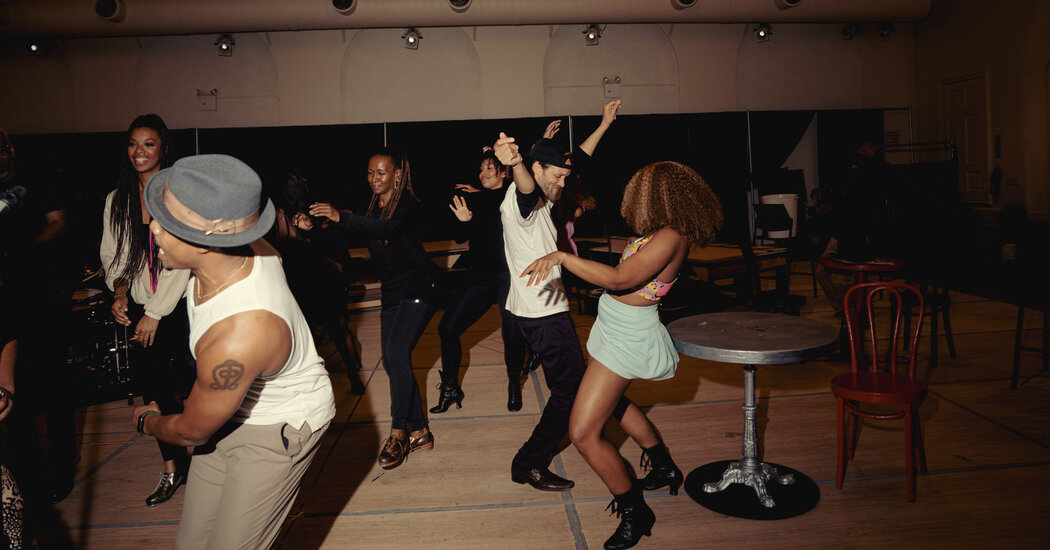

Majorette dance style is, hands down, one of the swaggiest ways a person can express themselves physically, which is why so many dancers (and people on TikTok) flock to it.

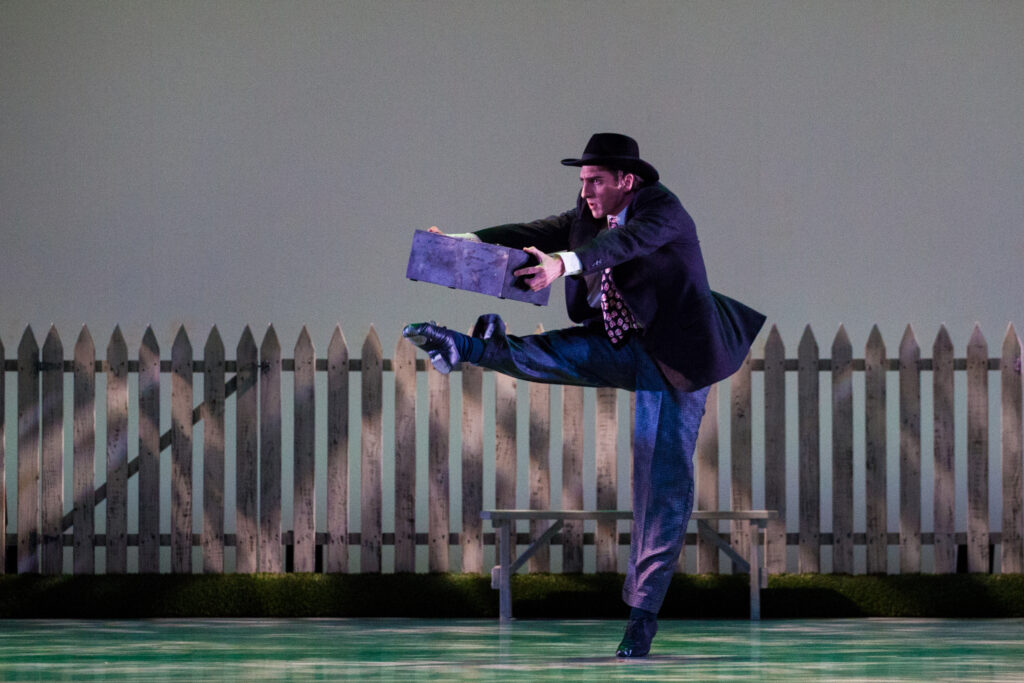

Majorette dancers, known for their bedazzled pageant-worthy costumes, synchronicity, and smooth-like-butter choreography, build intrigue and excitement for the bands they accompany during games, centering school pride and comradery. For those who have the discipline and can pull off the moves, these dance teams offer space for students to tap into profoundly artistic and powerful parts of themselves.

The majorette dance style, which is a fusion of hip-hop, jazz, and West African dance styles, is a celebration of the Black excellence that exists in Southern culture especially ― and in the legacy of HBCUs. This, of course, can sometimes come with some extremely limiting beliefs about what excellence looks like, how it should be expressed, and who is allowed to participate in it. However, North Carolina A&T’s first plus-size majorette team, Liquid Gold, is challenging these notions by reminding us the beauty of Black culture truly lies in the multitudes of its niches.

Jada Mayes and Leah Bell, students at the school, co-founded the team to create space for people with bigger bodies to explore majorette dance. Mayes grew up dancing ballet, jazz and hip-hop from the age of 5, but it wasn’t until she was a pre-teen that she realized she was drawn to the high-energy and semi-acrobatic dance moves of Black majorettes.

“I was in summer camp, we would make dance teams with each other, and one of my friends put me on to the show ‘Bring It,’” says Mayes, who talks about how the reality show, which previously aired on TLC and centers Miss D’s Dancing Dolls majorette team from Jackson, Mississippi, inspired her. “I liked their style and everything. So I was like, I want to try this,” says Mayes.

Mayes had previously been part of two majorette teams before forming her own at North Carolina A&T, the impetus being creating another type of safe space for those looking for it. She noticed that while the university’s dance teams did invite people of all shapes and sizes to participate, there was a tendency to underestimate individuals whose bodies did not fit the “norm.” In the world of majorette dancing ― and the world in general ― there’s the long held belief that people with thinner bodies are naturally athletic and more capable of pulling off the intense stunts seen in majorette choreography.

“There were a bunch of plus-size girls, and often they would be highlighted, I’m not gonna say in a bad way, but …I don’t know, it did not feel authentic,” says Mayes, adding that she often felt like she had to work harder to prove herself.

“All the tricks and everything, it takes a certain type of agility that people don’t expect plus-size girls to have,” she says. Ultimately, practice and motivation really determines how successful you are at this type of dance — and Mayes and Bell wanted to reinforce that truth.

“I know a good amount of majorette dancers who are beasts, that are powerhouses, and that can go toe-to-toe with anybody you put in front of them…who were discouraged about joining their [school’s] majorette team because there was nobody on that team that looked like them,” says Mayes, who feels like these barriers need to be broken down in order to truly put on display the full breadth of beauty and talent the majorettes embody.

The majorette dance is just one example of POC spaces that sometimes reinforce harmful body ideals. Thinness is seen as a virtue in most spaces on planet Earth, but especially in spaces where Black women hold public-facing positions. Black girls grow up observing people (especially women) around them hyper-fixate on having curves in only the “right” places. We are taught that being smaller can make us more palatable when our skin tone, facial features, socio-economic standing, accents, and ideas don’t.

Having a smaller body can influence our access to community and opportunities like jobs, other types of income, and in some cases — a spot on the team. But these beliefs are deeply damaging on a spiritual level, especially because the most natural and beautiful thing about our bodies is that they are all different and ever-evolving. By holding on to the toxic belief that thinner bodies are the only bodies able to succeed as dancers, athletes, and just in general, we are holding on to extensions of fatphobia and ableism. It’s time to let all that go.

Mayes and her team are joining a proud and successful cohort who have made space for plus-size people in the HBCU majorette dance world. She looks to Alabama State’s Honeybees and their recent collaboration with their school’s official majorette team, The Sensational Stingettes, as a sign of progress. She hopes that, at some point, Liquid Gold not only has a chance to collaborate with The Golden Delight Girls, A&T’s official majorette team, but that Liquid Gold itself is accepted as an official A&T majorette team, so they march side by side. And her greatest hope is that one day, the need for totally separate majorette teams will no longer exist.

So far, Liquid Gold has participated in on-campus events put on by other clubs, home football games, and off-campus events like Greensboro Pride, allowing them to garner their own fan base.

“We’ve been getting a lot of support. We’ve been collaborating with other organizations. They see us, and they like us. And that makes me happy,” Mayes tells me.

This support is what has kept Mayes going, along with her devotion to her teammates, whom she knows without a doubt deserve the opportunity to have the majorette experience. “To be able to finally perform, and to be able to finally show our talents to the school, to the world, it feels really surreal,” says Mayes.

[ad_2]

Source link